I wouldn’t exist if not for a gruesome mass murder in 1905 – we owe our lives to chance and chaos

Brian Klaas

How to celebrate a messy, uncertain reality by accepting that we, and everything around us, are all just flukes

On 15 June, 1905, Clara Magdalen Jansen killed all four of her children, Mary Claire, Frederick, John and Theodore in a little farmhouse in Jamestown, Wisconsin. She cleaned their bodies up, tucked them into bed, then took her own life. Her husband, Paul, came home from work to find his entire family under the covers of their little beds, dead, in what must have been one of the most horrific and traumatic experiences a human being can suffer.

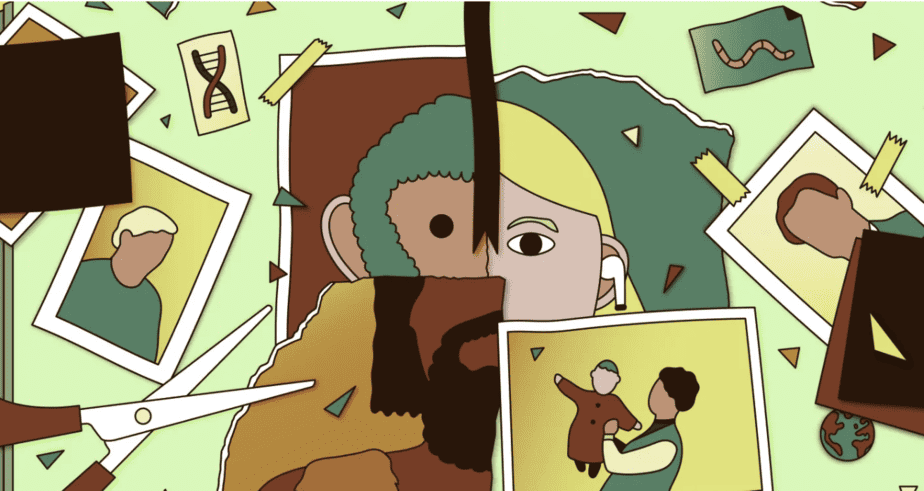

There is a concept in philosophy known as amor fati, or love of one’s fate. We must accept that our lives are the culmination of everything that came before us. You may not know the names of all eight of your great-grandparents off the top of your head, but when you look in the mirror, you are looking at generational composites of their eyes, their noses, their lips, an altered but recognisable etching from a forgotten past.

When we meet someone new, we can be certain of one fact: none of their direct ancestors died before having children. It’s a cliche, but true, to say you wouldn’t exist if your parents had not met in just the same, exact way. Even if the timing had been slightly different, a different person would have been born.

But that’s also true for your grandparents, and your great-grandparents, and your great-great-grandparents, stretching back millennia. Your life depends on the courting of countless people in the Middle Ages, the survival of your distant Ice Age ancestors against the stalking whims of a sabre-toothed tiger, and, if you go back even further, the mating preferences of apes more than six million years ago.

Trace the human lineage back hundreds of millions of years and all our fates hinge on a single wormlike creature that avoided being squished. If those precise chains of creatures and couples hadn’t survived, lived, and loved just the way that they did, other people might exist, but you wouldn’t. We are the surviving barbs of a chain-link past.

The Paul who came home to that little farmhouse in Wisconsin was my great-grandfather, Paul F Klaas. My middle name is Paul, a family name enshrined by him. I’m not related to his first wife, Clara, because she tragically severed her branch of the family tree just over a century ago. Paul got remarried, to my great-grandmother.

When I was 20 years old, my dad sat me down, showed me a 1905 newspaper clipping with the headline ‘Terrible Act of Insane Woman’, and revealed the most disturbing chapter in our family’s modern history. He showed me a photo of that Klaas family gravestone in Wisconsin, all the little kids on one side, Clara on the other, their deaths listed on the same date.

It shocked me. But what shocked me even more was the realisation that if Clara hadn’t killed herself and murdered her children, I wouldn’t exist. My life was only made possible by a gruesome mass murder. Those four innocent children died, and now I am alive, and you are reading my thoughts.

Amor fati means accepting that truth, even embracing it, recognising that we are the offshoots of a sometimes wonderful, sometimes deeply flawed past, and that the triumphs and the tragedies of the lives that came before us are the reason we’re here. We owe our existences to kindness and cruelty, good and evil, love and hate.

“We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones,” Richard Dawkins once observed. “Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Arabia.” These are the limitless possible futures, full of possible people, that Dawkins called “unborn ghosts”. Their ranks are infinite; we are finite. Our existence is bewilderingly fragile.

Why do we pretend otherwise? These basic truths about the fragility of our existence defy our most deeply held intuitions about how the world works. We instinctively believe that big events have big, straightforward causes, not small, accidental ones. As a social scientist, that’s what I was taught to search for: the X that causes Y.

From 13th-century monks to Google, we’re all index-linked

From feral to floof ball: The incredible evolution of cats

I am a (disillusioned) social scientist. Disillusioned because I’ve long had a nagging feeling that the world doesn’t work the way we pretend it does. The more I grappled with the complexity of reality, the more I suspected that we have all been living a comforting lie, from the stories we tell about ourselves to the myths we use to explain history and social change. I began to wonder whether the history of humanity is just a futile struggle to impose order, certainty and rationality onto a world defined by disorder, chance and chaos.

But I also began to flirt with an alluring thought: that we could find new meaning in that chaos, learning to celebrate a messy, uncertain reality by accepting that we, and everything around us, are all just flukes, spat out by a universe that can’t be tamed.

Such intellectual heresy ran against everything I had been taught, from Sunday school to grad school. Everything happens for a reason; you just need to find out what it is. If you want to understand social change, just read more history books. To learn the story of our species, dive into some biology and familiarise yourself with Darwin. To grapple with the unknowable mysteries of life, spend time with the titans of philosophy, or if you’re a believer, turn to religion. And if you want to understand the intricate mechanisms of the universe, learn physics.

But what if such enduring human mysteries are all part of the same big question? Specifically, it’s the biggest puzzle humanity must grapple with: Why do things happen? The more I read, year after year, the more I realised that there are no ready-made solutions to that enormous puzzle just waiting to be plucked from political science theories, philosophy tomes, economic equations, evolutionary biology studies, geology research, anthropology articles, physics proofs, psychology experiments or neuroscience lectures.

Instead, I began to recognise that each of these disparate realms of human knowledge offers a piece that, when combined, can help us get closer to solving this bewildering puzzle. The challenge of my new book, Fluke: Chance, Chaos and Why Everything Matters, is to try to join many of those pieces together, to yield a new, coherent picture that reframes our sense of who we are and how our world works.

When enough puzzle pieces snap together, a fresh image emerges. As we see it come into focus, there’s hope that we can replace the comforting lies we tell ourselves with something that approaches a more accurate truth.

We may find that flip disorienting. But we already live in disorienting times – of conspiratorial politics and pandemics, economic shocks, climate change and fresh society-bending magic, produced by the wizardry of artificial intelligence. In a world of rapid change, many of us feel lost in a sea of uncertainty. But when lost at sea, clinging to comforting lies will only help us sink. The best life raft may just be the truth.

Our world is more interesting and complex than we are led to believe. If we look closer, the storybook reality of tidy connections might give way to a reality defined by chance and chaos, an arbitrarily intertwined world in which every moment, no matter how small, counts. You’re reading this sentence because of a tragic mass murder 119 years ago. Nothing is meaningless. Chaos theory proves that everything produces ripple effects that emanate out endlessly.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself,” the naturalist John Muir once said, “we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” We are each hitched to one another, which yields a profound gift: everything we do matters, including whatever you decide to do now, when you go out to explore that wonderful, maddening, infinitely complex world that we call home.

Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything Matters by Brian Klaas is out now (Hachette, £20). You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy!

If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue or give a gift subscription. You can also purchase one-off issues from The Big Issue Shop or The Big Issue app, available now from the App Store or Google Play