The Existential Issues Facing Israel Are Heading Towards Explosion

– …

A year ago this week, Israelis took to the streets and felt that they had saved Israeli democracy. What became known as “Gallant Night,” not because of any gallantry, but after the defense minister whose firing Benjamin Netanyahu had just announced, wasn’t exactly the victory the tens of thousands protesting around Netanyahu’s house in Jerusalem and on Kaplan Street in Tel Aviv, hoped for. Netanyahu and his coalition would continue trying to assault Israel’s limited and fragile democracy. In many ways they still are. But it was still a pivotal moment.

The outpouring of public anger, backed up the next day by the announcement of a general strike, forced Netanyahu to stop in his tracks, agree to convene talks with the opposition over a more consensual judicial reform and ultimately rescind the firing of Defense Minister Yoav Gallant who had warned that he couldn’t vote in favor of legislation that was dividing the Israel Defense Forces.

It wasn’t the end. After a couple of months, the talks broke down, the coalition passed legislation eliminating the High Court’s use of the reasonability standard to hold the government to account and six months later, the High Court ruled, by the smallest of margins, that it was unconstitutional to deny its use. It was ultimately a victory, since the court’s powers remain unchanged, but only thanks to a majority of relatively liberal judges on the bench. Now two of them have retired and Justice Minister Yariv Levin, frustrated at the way his plans to eviscerate the judiciary have come to naught, is refusing to allow the appointment of new Supreme Court judges.

Israel’s democracy hasn’t been saved: How the Judicial coup eventually prevailed

Netanyahu’s crooked alliance with the Haredim is another feather of failure in his cap

Crisis over Haredi military service exemptions is a seismic event for Israel’s politics

But the conclusion of the majority of Israelis, both those who supported the overhaul and the opposition, from that episode is that the court’s powers and the relationship between it and the Knesset will have to be better defined in the future. Doing this will take a very different approach to the way the coalition tried to steamroll its legislation through last year.

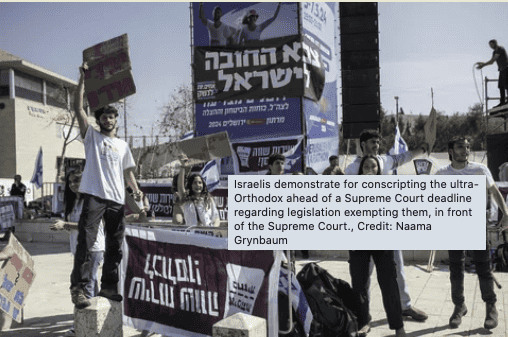

Israelis demonstrate for conscripting the ultra-Orthodox ahead of a Supreme Court deadline regarding legislation exempting them, in front of the Supreme Court.

Israelis demonstrate for conscripting the ultra-Orthodox ahead of a Supreme Court deadline regarding legislation exempting them, in front of the Supreme Court.Credit: Naama Grynbaum

It certainly can’t take place with Netanyahu still in office, as every move will be rightly seen as designed to intimidate the judges sitting in his corruption case, and perhaps his future appeals. But convening a constitutional assembly will have to be at the top of the next prime minister’s agenda if Israel is not to return to the brink of civil war, as it seemed to be a year ago.

This week, we had another pivotal moment courtesy of Gallant when the government failed to table a new law exempting ultra-Orthodox yeshiva students from military service. It was Gallant’s refusal to endorse a law which would enshrine a fundamental inequality between Israelis that prevented the government from kicking this can further down the road. It now seems all but inevitable that on Monday, once the High Court’s final deadline has passed, the historic exemption for Haredi men which has been in place from Israel’s founding nearly 76 years ago will have finally ended.

The two events in which Gallant dug his heels are of course connected. While there are many motives spurring on the various enemies of the Supreme Court, for the ultra-Orthodox parties, the main reason they wanted to drastically weaken its powers was to ensure that an exemption law would pass. Assuming that the exemption will indeed be void next week, they will try to restore it in the future, but it is hard to see an Israeli government doing so now that the public is so overwhelmingly opposed.

Defense Minister Yoav Gallant speaks to the media, last month.

Defense Minister Yoav Gallant speaks to the media, last month.Credit: Tomer Appelbaum

Any solution for a community that currently consists of 13 percent of the population that wishes to hold itself above the burden of the rest of Israeli society while enjoying benefits will have to be reached in a wider conversation, once again, not under a Netanyahu government which was founded on the basis of the Haredim being promised whatever they demanded.

The next government will have to hold a long overdue conversation about the future of the Haredi relationship to the state and the inadequacy of the “status quo” on matters of state and religion that David Ben-Gurion promised the rabbis on the eve of independence. Now, the Haredim will have no choice but to take part in it. It won’t be just about the national service of its young men, it will also have to address fundamental questions about education and employment if the Israeli economy can hope to thrive.

We still don’t know when the election to finally replace Netanyahu will take place, but the events of the past year have set up some of the most crucial conversations Israel must hold about its future the day after he goes. Does that mean it will have the most crucial conversation of all?

Ultra-Orthodox men clash with police at a protest against their enlistment, in Jerusalem.

Ultra-Orthodox men clash with police at a protest against their enlistment, in Jerusalem.Credit: Olivier Fitoussi

The Hamas attack and massacre on October 7 and the war that it triggered in Gaza were supposed to have “put the Palestinian issue back on the agenda.” At least that is what self-important pundits in the international media are constantly saying and writing. Perhaps. It’s just as likely that once there finally is a cease-fire and the long process of trying to work out who controls Gaza and the massive rebuilding project it will need, the world will once again lose interest in the depressingly intractable situation.

It seems almost unimaginable that the world will go back to business as usual, but it shouldn’t be. There are plenty of scenarios for this happening. If, just for example, Donald Trump wins the election in November, abandons Ukraine, withdraws from NATO and leaves Europe in the lurch, Gaza and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will likely be relegated to the margins of global attention. It will be up to the Israelis and the Palestinians to decide whether they can muster the political will to address their joint futures.

Israel’s agenda of existential issues is packed. Over the last twelve months, we’ve seen the dangers of allowing these problems to fester until explosion. Next year may finally be the year in which they are dealt with; not doing so could be fatal.