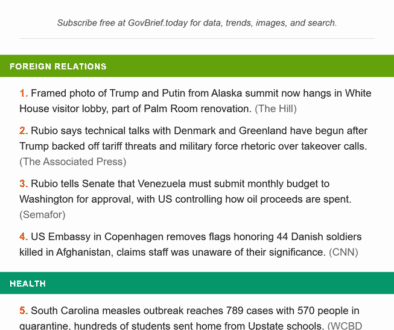

This Flesh-Eating Fly Is Spreading To The U.S. — And It Could Devastate Livestock Farming If Not Controlled

In a nutshell

- The flesh-eating New World screwworm fly, previously eradicated from North America, has returned and is spreading northward through Central America toward the US, putting millions of cattle and humans at risk.

- The parasite was successfully eliminated in the 1980s using sterile insect technique (releasing billions of sterile males), but current production of sterile flies may be insufficient for another eradication campaign.

- Climate change, lack of experienced personnel, and potential behavioral adaptations by the flies are making this re-emergence particularly challenging to control.

A flesh-eating parasitic fly is invading North and Central America. The consequences could be severe for the cattle industry, but this parasite is not picky – it will infest a wide range of hosts, including humans and their pets.

The “New World screwworm” (Cochliomyia hominivorax) was previously eradicated from these regions. Why is it returning and what can be done about it?

Flies fulfill important ecological functions, like pollination and the decomposition of non-living organic matter. Some, however, have evolved to feed on the living. The female New World screwworm fly is attracted to the odor of any wound to lay her eggs. The larvae (maggots) then feed aggressively on living tissue causing immeasurable suffering to their unlucky host, including death if left untreated.

Cattle farmers in Texas estimated in the 1960s that they were treating around 1 million cases per year.

Between the 1960s and 1990s, scientists and governments worked together to use the fly’s biology against it, eradicating the New World screwworm from the U.S. and Mexico using the sterile insect technique (SIT).

A female screwworm mates only once before laying her eggs, whereas the males are promiscuous. During the eradication process, billions of sterile males were released from planes, preventing any female that mated with them from producing viable eggs.

In combination with chemical treatment of cattle and cool weather, populations of the screwworm were extinct in the U.S. by 1982. The eradication campaign reportedly came at cost of $750 million, allowing cattle production to increase significantly.

For decades, a facility in Panama has regularly released millions of sterile flies to act as a barrier to the New World screwworm spreading north from further south.

However, since 2022 – and after decades of eradication – the New World screwworm has once again spread northwards through several countries in Central America. Cases exploded in Panama in 2023 and the fly had reached Mexico by November 2024.

Scientists have suggested several hypotheses for this spread, including flies hitchhiking with cattle movements, higher temperatures enhancing fly development and survival, and the possibility that females are adapting their sexual behavior to avoid sterile males.

Around 17 million cattle are now at risk in Central America, but worse may be to come. Mexico has twice as many cattle, and the spread towards the U.S. continues, where around 14 million cattle would be at risk in Texas and Florida alone.

Humans are not spared, with at least eight cases of the flies infesting people in Mexico since April.

Live Animal Ban Due To New World Screwworm Fly Threat

The U.S. has responded by temporarily restricting live animal imports from Mexico. The governments of the U.S., Central American countries and Mexico are also working together to heighten surveillance and work towards the eradication of the New World screwworm by stepping up sterile insect releases.

Sterile male screwworm pupae (juveniles) are currently produced and safely sterilized by irradiation at a rate of over 100 million per week at a facility in Panama. This is jointly funded by the USDA and Panama’s Ministry of Agriculture Development. However, a successful eradication campaign may need several times this number of sterile flies.

For example, sterile fly production for releases in Mexico in the 1980s were reportedly in excess of 500 million flies per week. To combat this shortfall, the USDA is focusing releases in critical areas of Mexico and is already investing US$21 million to equip a fruit fly production facility in Metapa, Mexico, to also produce 60 million to 100 million sterile screwworm per week.

Fly production, sterilization and release is a long process, and a reduction in wild screwworm populations would not be immediate. History has shown us that integrated control with anti-parasitic veterinary medicines are essential to repel flies and treat infestations as they arise.

Surveillance with trained personnel is also essential but is a great challenge due to an entire generation of veterinarians, technicians and farmers who have no living memory of screwworm infestations.

Finally, climate warming means that we may not be blessed with the cool weather that facilitated previous eradication, and further work is needed to determine how this will impact current eradication plans.

Hannah Rose Vineer, Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Infection, Veterinary & Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool. She receives research funding from the UKRI research councils.

Livio Martins Costa Junior, Professor of Parasitology. He receives funding from Brazilian agencies, including CNPq, CAPES, FINEP and FAPEMA.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.