This Little-Known Civil Rights Activist Refused to Give Up His Bus Seat Four Years Before Rosa Parks Did

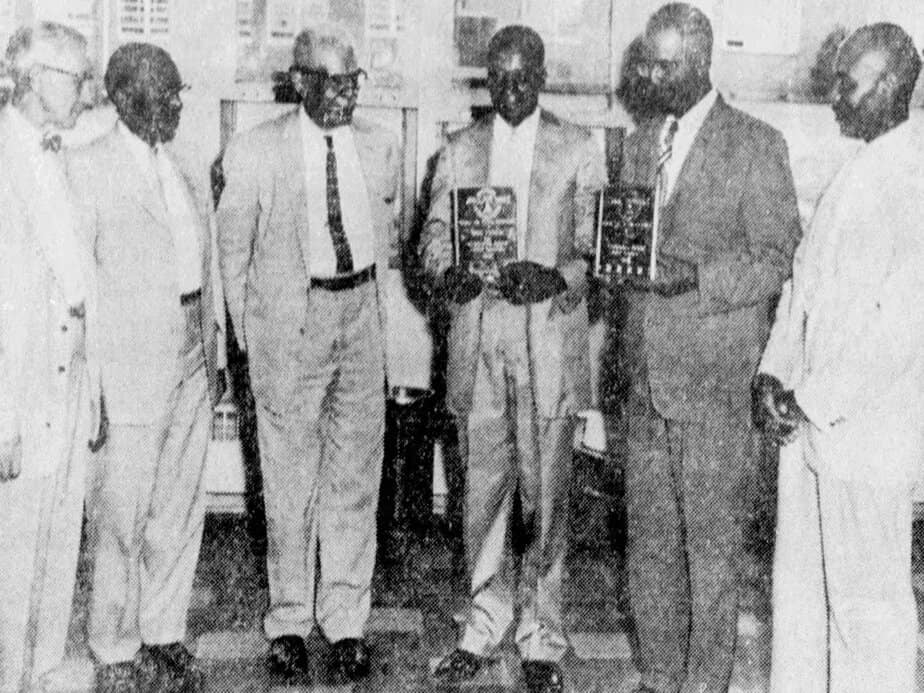

Smithsonian Magazine white logo Smart News History Science Innovation Arts & Culture Travel History Archaeology U.S. History World History Video Newsletter Science Human Behavior Mind & Body Our Planet Space Wildlife Newsletter Innovation Innovation for Good Education Energy Health & Medicine Sustainability Technology Video Newsletter Arts & Culture Museum Day Art Books Design Food Music & Film Video Newsletter Travel Africa & the Middle East Asia Pacific Europe Central and South America U.S. & Canada Journeys Newsletter At The Smithsonian Visit Exhibitions New Research Artifacts Curators’ Corner Ask Smithsonian Podcasts Voices Newsletter Podcast Photos Photo Contest Instagram Video Original Series Smithsonian Channel Newsletters Shop Untold Stories of American HistoryExplore the lives of little-known changemakers who left their mark on the countryHISTORYThis Little-Known Civil Rights Activist Refused to Give Up His Bus Seat Four Years Before Rosa Parks DidWilliam “W.R.” Saxon filed a lawsuit against the company that forced him to move to the back of the bus, seeking damages for the discrimination and mental anguish he’d facedTaryn WhiteJuly 23, 2024 7:15 a.m.A 1959 photograph of Saxon, who is standing third from leftA 1959 photograph of William “W.R.” Saxon, who is standing third from left Statesville Record and Landmark via Newspapers.comIn May 1951, William “W.R.” Saxon stepped aboard a Smoky Mountain Stages Inc. bus in Atlanta with his ticket grasped tightly in his hand. Bound for his home in the Southside neighborhood of Asheville, North Carolina, the Black insurance agent was no stranger to the pervasive Jim Crow discrimination of his time. But this seemingly routine ride turned into a pivotal moment when Saxon refused to move to the back of the segregated interstate bus—a full four years before Rosa Parks’ similar but far more famous act of civil disobedience. It’s unknown if Saxon’s case directly inspired later Black activists like Parks, but the lawsuit he subsequently filed against the bus company brought heightened media scrutiny and public awareness of civil rights issues in the South.Who was W.R. Saxon?Born in 1878 in Laurens, South Carolina, Saxon was the son of George and Caroline Saxon. Not much is known about his early life, but records indicate that he co-founded a local newspaper around 1901 and worked for the Laurens School District before moving to Asheville in the late 1920s.A 1955 photo of Saxon, who is shown at the far rightA 1955 photo of Saxon, who is shown at the far right Alabama Tribune via Newspapers.comSaxon’s life was marked by his dedication to social justice and equality. He was a Seventh-day Adventist, a traveling lecturer on public health issues and an insurance agent for the National Accident and Health Insurance Company. He was also active in the leadership of both the Asheville and statewide chapters of the NAACP.The 1951 bus ride wasn’t Saxon’s first experience fighting racist policies. Through his status as a prominent member of the Black community, Saxon was involved in a range of civil rights work, including advocating for voting rights. When Buncombe County officials denied three Black Asheville residents the right to register to vote in 1941, Saxon notarized the affidavits detailing the incident. As the Asheville Citizen-Times reported that May, the affidavits’ authors argued that Black voters “were forced to meet tests that were not required of white voters … in violation of their constitutional rights.”Saxon’s bus rideIn the early 1950s, segregation laws mandated that African Americans in the Jim Crow South sit at the back of the bus. When Saxon boarded his bus in May 1951, he sat in the third seat from the rear. Soon, another passenger told the bus driver to move Saxon “or there would be trouble,” per the Asheville Citizen-Times. The driver complied, but Saxon refused to relocate, contending that “he was comfortable in his seat, that he did not desire to move and that he was a passenger in interstate commerce,” the newspaper reported. Saxon seemed well aware of the groundbreaking 1946 case Morgan v. Virginia, in which the United States Supreme Court had ruled that segregated interstate bus travel violated the Constitution’s Commerce Clause. Yet racial norms in Georgia and North Carolina prevailed, maintaining de facto segregation on buses.Postcard of a Smoky Mountain Trailways bus driving through Great Smoky Mountains National ParkPostcard of a Smoky Mountain Trailways bus driving through Great Smoky Mountains National Park Wilson Library / University of Nort