Bela Borsodi

Dads bring their sons to Baseball Heaven so they can feel like pros. The facility, situated on an industrial lot off the Long Island Expressway, has recessed dugouts, proper bullpens, and stadium lights. On weekends, the lot fills with so many cars that minivans must illegally park on the roadway verge. Cleats click-clack on pavement, and cooler wheels groan. Fathers jockey for position to record their sons’ swings and fixate on pitch velocity, murmuring the incantation “What’s he at? What’s he at?” Between games, boys wander the park with Gatorade-stained lips and gnash on Big League Chew. Inside the café, televisions simulcast play on all seven fields. The turf is artificial, which means the grass at Baseball Heaven is always green.

Every father finds his own way to this Eden, and for Bobby Sanfilippo, it all started at a batting cage on an autumn day in 2008. Sanfilippo and his seven-year-old son were taking practice swings when a skinny man in a windbreaker marveled at the boy’s bat speed. He handed Sanfilippo a business card. How would his son like to try out for a travel baseball team called the Inferno? It would be expensive at $1,200 a season and require an aggressive schedule of forty-odd games a year, some of them at Baseball Heaven. It was a far cry from the dozen or so Little League games they were playing at the time. But Sanfilippo’s son—who loved baseball so much his bedroom had a custom Yankee Stadium fresco—was thrilled at the prospect. Sanfilippo was trying to figure out how to be a good dad and make his son feel special, and he figured travel baseball could play a big part in that. He had grown up in Brooklyn, in a cold house with a cold father, the owner of several bars in East New York. His dad was a rough guy, and he took little interest in Sanfilippo, who had to “grow up quick.” His father got a brain tumor when Sanfilippo was fifteen, and they didn’t patch things up before he died four years later. Sanfilippo was determined not to repeat the same mistakes with his little boy.

BOBBY SANFILIPPO

Sons grow up, and one day dads must leave Baseball Heaven, too. But Sanfilippo hasn’t moved on. During his years at Baseball Heaven, he found himself enmeshed in an epic dad-on-dad rivalry with a man named John Reardon that led tabloids to call him “a Suffolk County Steinbrenner,” “seriously sick,” and one of the worst dads in youth-sports history. Nine years later, he still keeps a file of dirt he dug up on Reardon, his alleged victim. In fact, Sanfilippo has been waiting for someone to call him up and ask for his side of the story.

Reardon hasn’t forgotten, either. “I don’t need closure,” he said, assuring me that his family “laughs about it sometimes.” And yet he still finds himself Googling Sanfilippo and his son late at night. Reardon still considers Sanfilippo a “jackass” and “pathetic.” His son is a “garbage kid.” He still remembers the last time he saw Sanfilippo, in a parking lot outside a baseball field.

“Can’t you just live your life?” Sanfilippo asked.

Reardon scowled. “Not until you’re dead.”

“If he builds it they will come,” read the Long Island Business News when Andy Borgia, owner of an office-supply company, sought financing for a new $8 million baseball complex. Baseball in Suffolk County had long meant stealing laundry soap to draw makeshift fields and twenty-inning neighborhood scrimmages. But by the late 1990s, parents craved more competition and facilities that would make their kids feel—and play—like pros. And when Baseball Heaven opened in April 2004, come they did.

“It had this aura, like its name,” said Vinny Messana, who was in seventh grade when Baseball Heaven opened. “If you succeeded on that field, you’d made it.” At first, being involved with the Inferno at Baseball Heaven was magical for Sanfilippo. Every time he drove into the parking lot, his heart beat a little faster. The crack of bats, crowds cheering. He would have spent every summer day there if he could. His son was so enthusiastic that he developed a trademark headfirst slide into first base. The Inferno steamrollered the competition, and Sanfilippo lugged home trophies as tall as his son. (A condition for Sanfilippo’s participation in this article was that his wife and son go unnamed to spare them further embarrassment.)

But the Inferno coach was a screamer who often reduced his seven-year-old players to tears. Parents constantly complained about “daddy ball,” the phenomenon in which a coach’s son always seemed to find himself playing the coveted shortstop position and batting first in the lineup. When a new coach, Rick DiRocco, took over the Inferno, he tried to keep things fun, but he was often forced to play peacemaker. Once, when a screaming match erupted between rival parents, he asked the opposing coach for help. “Don’t tell me what to do,” the man replied. “I’m a cop. I’ll shoot you.”

Baseball Heaven was partly responsible for the intensity, but what also gave Long Island baseball its unique flavor was the place itself. Nassau and Suffolk counties are home to 2.8 million people, most of them white and relatively prosperous. It has its own dialect—natives pronounce their home “Lawn Guyland”—and a reputation for dubious local figures.

A few baseball dads had sketchy backgrounds, too. One father, a manager at a Morton’s steakhouse, was part of a massive credit-card-skimming ring for which he would later be indicted. Another was fighting criminal charges for mortgage fraud and had a fearsome reputation: He was rumored to have driven his car into the home of someone who owed him money. (I couldn’t reach him to confirm or deny this.) A YouTube video later surfaced that reportedly showed him sucker punching an office worker.

Sanfilippo had his own rap sheet. In the mid-1990s, he was involved in a scheme luring foreign buyers to make “sizable deposits for the delivery of large quantities of cigarettes” that were then never delivered, according to court records. (“Everybody’s got an uncle who knows somebody,” he told me, by way of explanation.) In 2007 and 2008, he and his wife paid filmmaker George Stamou more than $300,000 to make Easy Street, a movie about his life as “a self-proclaimed former member of an organized-crime family,” according to a subsequent civil suit.

The Inferno played well, but as competition increased, parents hungered to win more. If Coach DiRocco kept a weak player in a tight game and they lost, parents went ballistic. They even took the unusual step of scouting players themselves and recruited Jack Reardon, a young phenom. He came with some baggage, however: his father, John.

John Reardon was built like a fullback. His cheeks flushed when he got angry, which was often. Reardon volunteered to keep the Inferno score book, but he was frequently at the dugout fence, screaming at players who made errors, especially Jack. His son played better when he wasn’t around. A few years before Jack joined the Inferno, the Department of Justice had charged Reardon for his involvement in a late-1990s Ponzi scheme in southern California that duped investors out of $45 million. Reardon eventually pleaded guilty to tax evasion. He avoided prison, but the conviction trailed him.

Both Sanfilippo and Reardon were cocksure, with dubious pasts. But Sanfilippo had charm and finesse, and he was thriving financially. He owned a five-bedroom mansion with an in-ground pool, a putting green, and a basketball court in a tony suburb. Reardon struggled in sales jobs and lived in a modest home. His life after the Ponzi scheme was a long glide into debt. He hadn’t been able to bend the world the same way Sanfilippo had.

BOBBY SANFILIPPO

In the summer of 2010, the Inferno coaches sent an email to parents with some devastating news: The team had too many players. If anyone was on the fence about the upcoming season, could they please quit now and obviate the need to make cuts? Sanfilippo had been surprised by the intensity of baseball parents, but Jack Reardon had upstaged his son on the field, and now he found himself getting emotional at even the prospect of his son getting the boot and Jack staying. Sanfilippo hit “reply all” and let rip. He promised to buy the team presents and trashed some families by name. The email shocked other parents, and DiRocco felt he had no choice but to ask Sanfilippo and his son to leave.

(Sanfilippo disputed that account, saying that his son asked to quit because of John Reardon’s temper. Multiple Inferno parents, however, remembered the nasty email.) Leaving the Inferno could have been a blessing for the Sanfilippos. Long Island travel baseball was getting more intense. Dads bought their sons weighted balls to build arm strength, but that could also lead to injuries. Long Island kids began appearing in the waiting room at the Hospital for Special Surgery in Manhattan, sheepish dads in tow. “Their opening salvo is ‘I didn’t let them pitch too much,’ ” said David Altchek, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in Tommy John surgery, a procedure typically reserved for pros.

After a loss, dads might congregate in the parking lot to grumble. If losses piled up, they took their sons and bolted to a new squad. And if his kid sat too many innings or a coach’s mediocre son batted too high in the order, a dad was liable to get pissed. When a father’s anger about “daddy ball” didn’t erupt in the stands, or at a hotel bar on a tournament trip, it found its way to an online message board, Called Strike Three, the emotional sewer for Long Island baseball families. The board was Internet 1.0, with cheesy graphics and an unwieldy interface. A moderator edited personal attacks, so parents gave one another nicknames like “Fidel,” “Fester,” and “McSlimeball.” Virtually everyone posted anonymously.

“I feel bad for your kid who has to wake up every morning knowing that his father is a big [expletive].”

“I doubt that, but your [sic] a delusional idiot so keep talking . . . I like the banter, its [sic] like a bad episode of Springer.”

“Before you call anybody an idiot, please proof read your response, your grammar is as good as your grip on reality.”

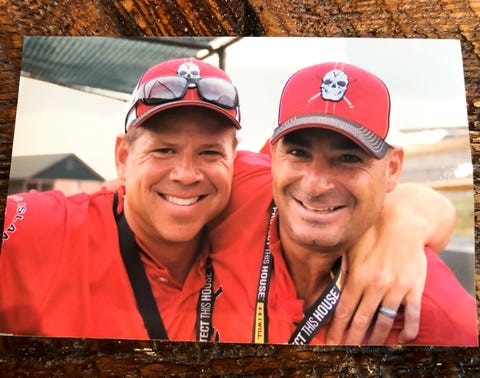

Sanfilippo and his son joined the Elwood Thunder, a low-key, no-drama team. It was fun, but after the Inferno, Sanfilippo had caught the travel-ball bug. He wanted to put together a powerhouse squad for his son, so he started his own team. He placed flyers on windshields at batting cages and took out an ad in Newsday to recruit top players. He helped create a team logo: a skull against crossed baseball bats. The team would be called the Long Island Vengeance.

While other teams were now charging upwards of $2,500 a season, Sanfilippo self-financed the Vengeance. Players got free bat bags, helmets airbrushed with skulls, and blood-red jerseys. The source of the money was unclear. Sanfilippo told me that “New Jersey friends” who liked his son bankrolled the team and that the cost wasn’t near the $50,000 that tabloids later reported. Many dads were happy to play free travel ball. “I was going through a bad divorce at that time, so it was a home run for me, no pun intended,” said Brian McCready, the father of an outfielder, who also helped coach.

Reardon was having money problems, too, and when he heard about a new, fully funded travel team, he inquired. But when he learned it was Sanfilippo’s squad, Reardon told me he changed his mind. (Sanfilippo said that when he got an email from Reardon, it was he who told Reardon that his family was not welcome. Whatever the case, one of them was badly snubbed.)

Early that spring, the Inferno and the Vengeance squared off, and Sanfilippo’s new team got stomped. Reardon shouted from the dugout at Sanfilippo’s ten-year-old son: “Learn how to play your fucking position!”

It was Memorial Day weekend 2012. Sanfilippo had recently recruited a handful of players from another team, and the Vengeance and the Inferno had a rematch. The game was nauseatingly close. Reardon sat on a bucket and chirped all game—so aggressively that the umpire twice cautioned him. The Inferno clung to a one-run lead. Jack Reardon was on the mound to close out the game. Sanfilippo’s son stepped into the batter’s box with two outs. He worked a full count, and then Jack fired one low and away. Called strike three. The Inferno had won again.

“Sit the fuck down, Sanfilippo!” Reardon screamed from the dugout at the ten-year-old who had just struck out. Roger Kalinowski, third-base coach for the Vengeance, swiveled around. “What are you, out of your fuckin’ mind?” he cried.

They kept arguing, and then Reardon emerged from the dugout carrying a baseball bat. (Reardon told me he did indeed get a bat but that it was a joke.) McCready saw the bat and lost it, and soon coaches were streaming onto the field. Several months later, a YouTube user named “anonymouslongisland” uploaded a cell phone video of what happened next.

Bela Borsodi

“What are you crying about?” Sanfilippo shouted at Reardon. “You won!”

McCready added, “Don’t mouth off. Just walk away, bro.”

At that, Reardon charged. “What are you gonna do?” he screamed. “What are you gonna do?”

Inferno coaches held back Reardon, finally muscling him off the field as he shouted, “Suck my dick!”

“My son was crying,” Sanfilippo told me. “His son was crying. Half the dugout was crying. It was horrible. It was fuckin’ horrible.” Reardon, he decided, was “the kind of guy who will punch you peeing in the stall.”

Of the video, Reardon told me: “I don’t even think that was me, to be honest. And even if it was, it was probably just the portion where I was joking.” But Reardon looks deadly serious in the video, which now has 1.2 million views.

On the Inferno side, Coach DiRocco had seen enough of Reardon and banned him from the dugout. DiRocco also decided that drinking in the stands was fueling bad behavior. He asked parents to lay off the red Solo cups at games.

“Is that just for a little while,” a mother asked hopefully, “or is that forever?”

Sanfilippo told me he didn’t give Reardon another thought that summer. He had a lot to do. Sanfilippo paid for tournament registrations, flights, uniforms, and food on the road. He took the boys to Yankees games, where they sat behind the home dugout. The Vengeance played more than eighty games that season.

The Vengeance were becoming the Sanfilippo show—literally. In August 2012, he met TV producer Jon Schroder at a diner in Manhattan. Sanfilippo was TV gold. (“I wish I would’ve filmed the breakfast,” Schroder told me.) They agreed to shoot a sizzle reel for a reality show. When Schroder visited Sanfilippo’s mansion in Huntington for a massive backyard pool party, he thought he’d stepped into an alternate universe. Mark Giacometti, a Vengeance dad, was a chef at a gourmet grocery store, and he brought mountains of baked ziti, chicken francese, heroes, and steak with brown sauce. Long-nailed mothers and tattooed fathers cursed and gossiped and ate. Sanfilippo paid a barber to shave a skull into the back of his son’s head.

BOBBY SANFILIPPO

The team’s schedule was grueling. “We were constantly playing fuckin’ baseball,” McCready told me. “It was fuckin’ brutal, bro.” Before a tournament, Sanfilippo would sit at his kitchen table debating the lineup with his wife, knowing that one wrong move on his magnet board could make a dad go crazy. Vengeance parents logged on to Called Strike Three to anonymously gripe. But as long as Sanfilippo was cutting checks and grilling rib eye steaks, they didn’t openly revolt.

For Sanfilippo, his son was playing well and having fun. To the TV crews, he was open about what motivated him. “When I hear people talkin’ their dad this, their dad that . . . I wish I could say that,” Sanfilippo told the camera. “But I know my son’s gonna be able to say that.”

John Reardon? Furthest thing from his mind.

One June morning, it was John Reardon’s turn to drive the car pool to school when he noticed a blue Mini Cooper on his street. It was unusual—people rarely parked there. As he pulled away, the Mini Cooper did a quick U-turn and followed him and the four kids in his car all the way to Burr Intermediate. Reardon walked Jack and the others into school and then headed off. The blue car stayed in his rearview.

Reardon made a right turn, then another right, figuring he was just paranoid. But the driver, a bald guy, continued to follow. On a dead-end street, Reardon made a U-turn, hoping to box in the Mini Cooper, but the tiny car slipped away. Two months later, on August 23, 2012, Reardon was at a business dinner when his phone buzzed with a text. He peeked down.

“See you at Baseball Heaven, scumbag.”

Three minutes later, his phone beeped again. This time he was staring at a picture of his own home and a message: “I’m your bad dream motherfucker.”

Then, thirty minutes later, a blurry photo, taken with a long-distance zoom lens, of Reardon’s wife. The texts went on through the afternoon, including two more photos of his home. “Figured you for a nicer house, did you spend all of that money you stole on lawyers, you fat jerkoff?”

Reardon wondered if the texts were from an aggrieved Ponzi-scheme investor, someone still pissed about money lost a decade earlier. Or maybe it was a prank. Reardon didn’t tell his wife. He didn’t want to worry her.

But the messages continued into the following day, with more fuzzy, long- distance photos of his wife. “You will never see it coming Reardon,” read one.

Reardon’s phone soon buzzed with a new photo: a crystal-clear image of little Jack Reardon waiting for the school bus with the message “Maybe I’ll pick him up at the bus stop for you next week. . . . When I get done with you you’ll move, sleep tight, asshole. You have no idea who you are dealing with, tell Jack not to talk to strangers. You’re an asshole, another guy you fucked over.”

The next day, Reardon was at Baseball Heaven for a tournament. Between games, Jack vanished. Reardon checked the field, the dugout, and the concession stand. He started to panic. Then he saw Jack coming out of the bathroom. Reardon rushed over. Jack looked up and asked, “What’s wrong, Dad?”

The reality-TV crew set up at Baseball Heaven in the afternoon of September 21, 2012. The Vengeance parents were excited—if the show got green-lit, they all stood to make good money. It was the first inning, and Sanfilippo was coaching third base when a Vengeance dad whispered to him through the fence that Suffolk County detectives were looking for him.

Sanfilippo saw officers blocking the exits. When the inning ended, he walked up to the lead detective, whose name Sanfilippo recalls as “McCloud or some fucking shit.” What follows is Sanfilippo’s account of what happened next. (A Suffolk County Police Department spokesperson declined to comment, as the case records are currently sealed.) “Take your fuckin’ mic off, Sanfilippo,” the detective said. Three plainclothes police officers stood around him. They asked if he knew John Reardon.

“Yeah, I know Reardon,” Sanfilippo said. “He’s an asshole.”

“Oh, so you don’t like him?” the detective asked. He asked for Sanfilippo’s phone.

“My phone’s in my coaching bag, which is in the dugout,” Sanfilippo said. “Be my guest and go get it.”

“Not that fuckin’ phone. The throwaway phone. The burner.”

Sanfilippo shut up. His wife called their lawyer. A cop spun Sanfilippo around and started handcuffing him while another officer laughed.

“Don’t do this here,” a third officer pleaded, hoping to shield two dozen kids from the arrest.

“No,” the lead detective said. “He’s gonna do the walk.”

BOBBY SANFILIPPO

If parents or players said anything, Sanfilippo didn’t register it. All he heard was ringing in his ears. Officers marched him beyond the cameras and out of Baseball Heaven. Police shoved him into the back of a squad car, with his hands cuffed in reverse so they’d fall asleep. Sanfilippo was scared. He claimed the officer punched him in the ribs, which is when he knew he “was fucked.”

At the station, an officer latched his cuffs to a wall hook. Sanfilippo asked to use the bathroom. The officer gave him another punch in the back and kicked away the chair so he couldn’t sit. Sanfilippo threatened to defecate on the floor until he was allowed to use the toilet.

Sanfilippo soon overheard a phone call. “Don’t worry, Johnny,” he heard the officer say. (Of the roughly 3.2 million men named John in America, Sanfilippo was sure the cop was talking to John Reardon.) “We got his fuckin’ photo goin’ to everybody. The only one left I gotta fax it to is Newsday.”

That night, officers cranked up the air conditioning and handed out blankets to other inmates. Sanfilippo shivered on a concrete bench. If he’d had his phone, he could have read Newsday’s breaking story, published just after midnight: youth baseball coach stalked rival.

In the morning, TV cameramen gathered outside the Fourth Precinct, where they had a clear view of Sanfilippo as officers marched him out in handcuffs. He was still wearing his black Vengeance shirt. “Disgruntled parents that don’t make travel teams do crazy things,” Sanfilippo said to a camera crew, a reference to his refusal to let Jack Reardon join the Vengeance. “That’s travel baseball for ya.”

“So you’re innocent?”

“Absolutely. Absolutely.”

A judge released Sanfilippo, and a producer drove him home. Sanfilippo’s wife was a mess. After the arrest, she had downed two Xanax. Parents gathered to “help,” including the dad in the midst of a credit-card-skimming case. He was so paranoid that he burned Sanfilippo’s cell phone charger on the barbecue, suspecting it contained a police bug.

The Vengeance had previously scheduled a pool party for that afternoon, and Sanfilippo insisted on going ahead with it. Parents arrived with food and a cake decorated with the team’s skull logo. The TV crew trailed Sanfilippo around the party. Away from the kids, he unloaded.

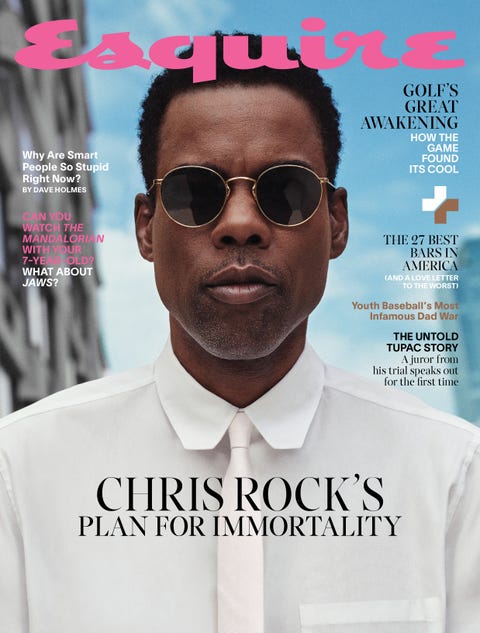

This article appears in the Summer 2021 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

“I tell you what, this fuckin’ John Reardon is the reason why I spent the past twenty fuckin’ hours in jail, because of that cocksucker,” Sanfilippo said, gesturing wildly. “And if he was here right now, I would fuckin’ beat him down to the ground.”

The Vengeance parents weren’t sure what to make of it. Some thought the whole thing was a practical joke. Schroder, the producer, suspected Sanfilippo had staged the arrest to create drama for the sizzle reel.

As details emerged, though, the gravity of the situation sank in. Detectives had tracked the sale of a phone card to a CVS pharmacy a few towns away. Reardon had come down to the Fourth Precinct to look at security footage. He couldn’t quite make out the face, so he asked Coach DiRocco to come, too. They fingered Sanfilippo in his Vengeance gear, leaving the store with a phone card and a case of water.

Reardon feasted on the media attention. Suffolk County police had indeed called to say they were tipping off journalists, he told me. (They also relayed that Sanfilippo cried all the way to the precinct.) Reardon obtained an order of protection against Sanfilippo. The more Reardon talked to reporters, the more the story went viral—a sports dad turned stalker over a strikeout. “It all started with a swing and a diss,” the New York Post wrote. On Good Morning America, George Stephanopoulos chuckled at the end of a two-minute segment and asked, incredulously, “Long Island Vengeance?”

Sanfilippo had become a celebrity, and in all the wrong ways. After his arrest, at a game on Staten Island, a dad heckled the team from the stands. When the Vengeance pulled ahead, he started in on Sanfilippo: “What are you gonna do?” he shouted. “You gonna come take pictures of my kid?”

Called Strike Three lit up with comments from parents reveling in schadenfreude at a rich dad finally cut down. “I heard a new shipment of furs fell off the back of the truck. I guess Sanfilippo can go shopping for a new player!”

“All the wins in the world can’t hide the fact that you allow your kid to be around, coached, bought, and sold by a crazy, stalking, lunatic criminal.”

Sanfilippo said he began to worry about his safety. He spotted unmarked cars tailing him as he left his home. His wife was at the nail salon when she noticed the detective who had arrested her husband watching her through the window.

“I think we gotta move,” Sanfilippo told his wife. “They’re gonna make me disappear. I know it.”

In the meantime, Sanfilippo paid $500 to have off-duty law enforcement shadow him at games; he wanted witnesses in case Reardon falsely claimed he’d violated the order of protection.

The producers pressed ahead with the sizzle reel. “I know I could depend on every single person on this team,” Sanfilippo’s wife told the camera.

But she was wrong. “It was fifty-fifty people believing the stalking charge,” said Giacometti, the chef and father of a Vengeance player. He wasn’t sure what to think, but he’d had enough. In May 2013, Giacometti and a few others pulled their kids off the team. Sanfilippo was furious. They had eaten at his home, swum in his pool, and worked out on his dime. Now they were splitting. A few months later, Sanfilippo saw Giacometti near the snack bar at Baseball Heaven and went out of his way to brush past, looking for a fight.

“Sanfilippo, no handshake?” Giacometti asked. “Mark,” he said, “why don’t you go fuck your mother?”

The case against Sanfilippo seemed weak, said his lawyer James O’Rourke. And Sanfilippo’s hunch about the police hadn’t gone away. He had friends in law enforcement, and he told me one of them had made a frightening connection: John Reardon was distantly related to James Burke, the police chief of Suffolk County. (Reardon denied this, saying that he “never met that guy. I never talked to him.”) Around this time, Newsday began reporting on Burke and corruption in his department.

Sanfilippo weighed his options. He was tempted to go to trial—so tempted that he bought vanity license plates that read DISMSSED. But a good defense might cost $40,000. And even if he won, his reputation had already taken a beating, and his son had been humiliated. In February 2014, Sanfilippo pleaded guilty to a single count of disorderly conduct and paid a $120 fine. Outside afterward, a friend photographed him flipping off the courthouse.

But Sanfilippo’s friend in law enforcement assured him something big was going down at the Suffolk County Police Department. “Shit’s gonna hit the fan,” he promised. “Sit back and watch. Get some popcorn.”

It was still dark out on the morning of December 9, 2015, when unmarked cars pulled up to a home in the hamlet of St. James. Agents wore trademark FBI windbreakers. Burke, the police chief, chatted calmly with them as they placed him in handcuffs.

Sanfilippo’s friend had been right. The Suffolk County Police Department wasn’t just dirty—it was about to become one of the most notorious law-enforcement agencies in America. Burke had run the department like the KGB, federal prosecutors later said. Loyal officers, whom Burke dubbed his “palace guards,” routinely surveilled and harassed rival cops and carried out personal vendettas. Thomas Spota, the county district attorney and Burke’s close ally, meanwhile “operated in a manner more akin to criminal enterprise,” federal prosecutors alleged. In December 2012, just a few months after Sanfilippo was arrested, police had nabbed Christopher Loeb, a young heroin addict, for breaking into Burke’s car. In an interrogation room, Burke and others beat Loeb and threatened to give him a “hot shot,” a fatal injection of heroin, and make it look like an accidental overdose. A judge later set Loeb’s bail at $500,000, an astronomical figure for such a petty crime.

Sanfilippo ticked off the similarities to his own arrest—same precinct, same jailhouse beating, same bogus judicial proceedings.

BOBBY SANFILIPPO

“Anything goes with Burke,” said Pat Cuff, a former Suffolk County police commander who testified about his disgraced former boss at a related corruption trial. “There is no bottom. Nothing would surprise me.”

Sanfilippo felt vindicated. But the stalking case still trailed him. The reality show never got picked up. In 2016, Sanfilippo wrote a memoir, Called Strike Three, to exonerate himself—some iteration of the word fuck appears ninety-three times in 182 pages—but he never published it. He considered hiring ReputationDefender, a company that specializes in cleaning up online search results, but balked at the cost.

And all the while, Sanfilippo claimed, although his son was working hard and getting better at baseball, coaches, college scouts, and journalists who compiled power rankings looked askance at the boy.

In 2017, when Sanfilippo’s son was in tenth grade, his school faced off against Jack Reardon’s. Sanfilippo left the game early to avoid a scene. When he reached the parking lot, he heard heavy footsteps behind him. Like so much of their saga, both men remember it differently. But they agree that Sanfilippo brought up Reardon’s tax-evasion conviction, and they nearly came to blows.

“Reardon, do me a favor,” Sanfilippo said. “Either throw the first punch or get the fuck away from me.”

“There’s gonna be a day when I bump into you and nobody’s gonna be around,” Reardon said. “There’s gonna be no cameras. No videotape. We’ll see what happens.”

Sanfilippo reminded me of my friend’s dad growing up in Brooklyn, who was unpredictable in every way except that he was always on our side. I didn’t want to believe he’d sent those horrible messages. But the more I dug into the corruption claims, the less I could verify.

Cuff, the former police commander, was dubious about Sanfilippo’s claims. “In all candor, I probably would’ve heard something about it,” he told me. Two other high-ranking officers stationed at the Fourth Precinct in September 2012 were skeptical as well. Sanfilippo wouldn’t connect me with the friend he claimed had found that supposed connection between Burke and Reardon. Rob Trotta, a retired detective who is now a Suffolk County legislator and outspoken critic of his old department, told me that after the corruption investigation came to light, prison inmates began regularly sending him letters claiming, conveniently, that Burke had framed them, too.

And I was learning more, not about Sanfilippo’s past but about his present. In 2019, an Alabama bankruptcy trustee sought to recover more than $3 million from Sanfilippo that he had received from Timothy McCallan, the alleged mastermind of a $107 million debt-counseling scam. The trustee alleged that Sanfilippo and his companies had helped McCallan hide stolen money. The case was dropped after Sanfilippo agreed to provide information to the trustee.

O’Rourke, the defense attorney, had recently destroyed his files for Sanfilippo’s stalking case. And Suffolk County had sealed the criminal files. Only Sanfilippo himself could access them, and I asked him repeatedly to do so. “It’s not happenin’,” he told me. “It’s stayin’ sealed, pal.”

I met with Sanfilippo this past February. He lives down south now. (Another condition for this article was that I not reveal exactly where.) He and his wife crossed the Verrazzano Bridge in September 2019 and never looked back. He’s building a new home on a quiet lane in a gated community. There will be plenty of room for the dozens of trophies, game balls, and other mementos from his summers at Baseball Heaven.

I arrived early at an overpriced brunch spot near his home and staked out the restaurant, hoping to observe him before we met. But Sanfilippo immediately identified me as he and his wife drove up in a golf cart. “I thought that was you,” he said, crushing my fingers in an iron handshake. “I looked you up on YouTube.”

BOBBY SANFILIPPO

Sanfilippo swaggered into the diner like a guy who could handle himself in a fight, took the seat he wanted, and marveled at his good fortune. “It’s a fuckin’ fairy tale,” he said in his Brooklyn accent, a little too loudly for the southerners at the next table. But he was circumspect with neighbors like these. He knew when someone had just Googled him. They went from friendly waves to giving his golf cart a wide berth.

We spoke for hours. Sanfilippo was still worried about Reardon, and he raged about the police, traitorous parents, and the toll the scandal had taken on his family. One dad who had bailed on the Vengeance, the credit-card skimmer, had recently reached out. “He said, ‘Tell your wife I miss her meatballs,’ ” Sanfilippo said and smirked. “I got some meatballs for ya.”

But his son was doing well. Sanfilippo was proud of the boy, who was now a young man playing college baseball and staying out of trouble. That afternoon, his son called every hour, as he always does when driving long distances.

Sanfilippo wanted to know if I had a kid. Other baseball dads I spoke to were the same. They usually asked right after revealing that they’d let their son play one hundred games of baseball in a single year, or the number of ninety-dollar half-hour hitting lessons they’d purchased, or why they’d stayed on a team after parents got in a fistfight at Applebee’s. They wanted to find out if I was a fellow traveler, someone who could understand what had been, in hindsight, collective insanity.

“I chose to be the opposite of my dad,” Sanfilippo said. His father’s final years were spent in a hospital bed in their living room, and Sanfilippo pumped gas after school to help pay the bills.

“How much of your parenting is a response to that?” I asked.

“All of it,” he said.

Sanfilippo excused himself to go to the bathroom. When he returned, he sniffled a few times, dabbed at his eyes, and then stared into the distance.

That night, I was sitting at a bar when my phone lit up with old videos of Sanfilippo’s son smacking base hits. The next night, after another lunch together, he texted me photos of game balls and plastic prizes.

Sanfilippo still couldn’t process the guilt: His notoriety had turned scouts off his son. “I deal with that every day, and it’s fucked up,” he said. But he couldn’t bear to dissociate from the experience, either. Those summers were the best of his life. They still made his heart full. Memory can be a garden or a prison, and Sanfilippo was trapped in Baseball Heaven.

And then, when I returned to New York, John Reardon surfaced again. He agreed to have lunch.

Long Island travel baseball today makes 2012 look quaint. Squads aren’t just “teams”; they’re “organizations,” some of which charge upwards of $3,500 a season, plus thousands more for airfare and high- profile “showcase” tournaments with college scouts. Vinny Messana, who remembered Baseball Heaven opening when he was in seventh grade, today runs Axcess Baseball, a website devoted to covering Long Island teams. The site has banner ads for local orthopedic surgeons who perform Tommy John operations on pitchers as young as twelve.

Baseball Heaven is owned by Steel Partners, a holding company with $1.6 billion in annual revenue and additional interests in banking, defense, and energy. The facility has a new $1.9 million indoor space and, before Covid, hosted more than half a million fans per year. Parents pay thirteen dollars per month to stream games online—and take screenshots of bad calls by umpires, which they post to social media. Andy Borgia, the office-supply- company owner who founded Baseball Heaven, has plans to replicate the model in Connecticut. I met John Reardon at Mannino’s, an Italian restaurant a short drive from Baseball Heaven. Reardon had grown a goatee, but he still had that stocky build and red face that looked ready to pop. He had been keeping tabs—he knew the cost of tuition at the elite sports academy that Sanfilippo’s son had attended ($85,000), where the kid played college ball, and even the town where the Sanfilippos had relocated. But over calamari, he denied framing his rival or even knowing Burke, the disgraced ex–police chief. “Imagine being able to go around having people arrested,” he said. “That’d be nice.”

Jack Reardon’s baseball career had flourished. He had ranked sixth on a local Blue Chip prospect list and was playing at the University of New Haven. It was still early days, but one former coach of his said he might yet be good enough to play pro ball.

But while Sanfilippo had continued to find financial success, Reardon’s life had gone in the opposite direction. A for sale sign hung outside his home. “Good time to sell,” he told me. In fact, the family was in financial trouble. His wife had recently filed for bankruptcy for a second time. On the petition, among their monthly expenses, she listed $400 for Jack’s travel baseball.

I asked about the Ponzi scheme, and Reardon was open about it. His good friend Kenny had recruited him, and they were sure they’d made their big break. They invested millions of dollars of family money before realizing they themselves had been duped. The convictions still haunted their professional lives.

“How did you know Kenny?” I asked.

“How?” Reardon asked. His face went red. “I was engaged to his sister.”

When she was diagnosed with cancer, Reardon gave up his whole life to care for her. “The worst part was after the third year,” he said. “They gave her the all clear that she was good.” The cancer came back soon after. She died in 1991. She was twenty-four.

We ordered lunch, but Reardon barely touched his sandwich. He was suddenly in an expansive mood. You’re not yourself when your son is on the field, he said. Something takes over your brain.

“Do you have kids?” he asked.

My first child was due in a month, I told him.

“So this is what’s gonna happen. You’re gonna have a kid. And you’re gonna be like, ‘Oh, man, this kid’s gonna be president. This kid’s gonna be on the Yankees. This kid’s gonna be, you know, whatever he wants to be.’ And then it’s like, ‘Well, he’s not gonna be president.’ ”

Reardon smiled. “I’ve kinda been lucky that Jack has kept me going, sports-wise,” he said. “So I can still keep that hope alive.”

Reardon and I said goodbye in the parking lot. The sun was setting, and I sped home to my unborn child. Across the median, fathers rushed past me into the Long Island suburbs. Amazon packages had landed on their doorsteps that afternoon containing bats, balls, wristbands, cleats, eye black, glove oil, andother adhesives to put broken things back together.

Reardon had lost someone he loved, and Sanfilippo wanted to love someone he’d lost. Sanfilippo’s life had not started as he deserved, and Reardon’s was not going as he’d hoped. Baseball Heaven wasn’t about ego, and it certainly wasn’t about baseball. It was a time machine, a black hole, a one-shot portal to pasts and futures that needed fixing.

But Sanfilippo and Reardon had ruined it for themselves and each other. And so they could not leave. Not yet.

The sun has set over the Long Island Expressway. The fans are gone, and the gate is closed. The grass that is always green has turned blue. And Sanfilippo and Reardon are in opposing dugouts, disappearing in twilight. They wait for what we all wait for: to suddenly be standing in the batter’s box ourselves. We’re ten years old and knobby kneed, behind in the count, when the man we will become stands up in his seat, cups his hands, and shouts that he loves us.

David Gauvey Herbert David Gauvey Herbert writes about crime, subcultures, and general weirdness for New York Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, and The New Yorker.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io