by Deirdre Mask

In the early weeks of the COVID pandemic, several members of Congress introduced a bill to name the D.C. street in front of the Chinese embassy after Li Wenliang. Wenliang was the Wuhan doctor who was reprimanded after sounding early alarms about COVID-19, and later died of the disease himself. “May this serve as a constant reminder to the world and to the Chinese Government,” Representative Liz Cheney announced, “that truth and freedom will prevail, that we will not forget the bravery of Dr. Li, and that the Chinese Communist Party will be held accountable for the devastating impact of their lies.”

The practice of retaliatory street renaming is so familiar it has its own Wikipedia page. In 2016, the Senate had voted to rename the same street Li Xiaobo Plaza, after the Chinese Nobel Prize Laureate who has criticized the communist regime (the Chinese government threatened “serious consequences” if the bill passed and President Obama said he would veto the bill, arguing that there were more productive ways to engage with China). In 2018, the D.C. City Council voted to change a section of the road in front of the Russian embassy to Boris Nemtsov Plaza, after the slain critic of Vladimir Putin. The area in front of its old embassy had been named Andrei Sakharov Plaza, after a Nobel Prize-winning dissident.

Americans aren’t the only ones to see the value in retaliatory street naming. In 2018, amidst disagreements over the U.S’s stance on the Syrian War, Turkey named the street for the new US Embassy in Ankara after Malcolm X. Long before that, Calcutta named the street the American consulate sits on Ho Chi Minh Sarani to protest the Vietnam War. And, as I describe in The Address Book, a group of teenage boys changed the name of the street in front of the British embassy—Winston Churchill—to Bobby Sands Street, after the Northern Irish hunger striker. The embassy knocked through a wall to devise a new entrance and avoid using the name.

And then there’s Kudirat Abiola Corner, right in front of the Nigerian consulate in Manhattan, at Second Avenue and 44th Street. Kudirat Abiola was the second wife of Moshood Abiola, the twenty-third and first surviving child of a cocoa merchant. (His parents called him Kashimawo,” which in Yoruba reportedly means “Let us watch and see whether this one too will die.” On his fifteenth birthday, they finally gave him his proper name.) Moshood Abiola became a wildly rich businessmen and keen politician, easily winning Nigeria’s 1993 presidential election. But soon after, the military government annulled the election and threw him in prison, where he would eventually die in custody. His wife and greatest champion, Kudirat, was shot in the head the same day she was supposed to leave to attend her daughter’s Harvard graduation.

So why name a street after her in New York, more than five thousand miles from her home? Around the time she was assassinated, activists like Michael Fleshman at the Africa Fund were fresh off successes in the movement against apartheid. They decided to try to direct the energy of that movement toward protesting Nigeria’s brutal military rule. Soon, they struck on a cheap but effective weapon: a New York street named after Kudirat, right outside the Nigerian consulate. Hearings for Kudirat Abiola Corner became a public circus, with protesters hired by the Nigerian government catcalling speakers like Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka and former Mayor David Dinkins.

When the street name was approved, the Nigerian government furiously petitioned the State Department and challenged the renaming in New York Supreme Court. The judge was unimpressed with the argument that the city’s decision intruded on U.S. foreign policy. “But what dangerous adverse name-calling could occur?” the judge asked. “Might Nigeria offend New York City by naming the street outside the United States Embassy ‘Boston Red Sox Boulevard’ or ‘Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra Drive’?” Nigeria, unable to change New York’s mind, instead named the street in front of Lagos’s U.S. Embassy after Louis Farrakhan.

Changing a street name sounds harmless, but countries care deeply about their reputations. Simon Anholt is an expert on the links between national reputation and international relations. Most people, he has explained, don’t really go beyond clichés when they think about other countries and cities—Paris is about style, Tuscany the good life, Japan technology, and so on. A key task of any government is, according to Anholt, to “earn a national reputation that is fair, true, positive, attractive, memorable, genuinely useful to their economic, political and social aims, and honestly reflects the spirit, the genius, and the will of the people.” So targeting a nation’s pride with an embarrassing street name is surprisingly effective.

One man who testified in favour of Kudirat Abiola Corner was Walter Carrington. Carrington, the former American ambassador to Nigeria, had been just one of four black students in his class when he came to Harvard in 1948, and had founded the university’s NAACP chapter. As a young man, he had befriended Martin Luther King, Jr. and debated Malcolm X as an undergraduate. Later, he became a director of the Peace Corps and an ambassador to Senegal. Throughout his time as an ambassador in Nigeria, he had spoken out vigorously against the military regime, at great personal risk. Kudirat Abiola had been in his office just days before she was assassinated.

When I spoke to Carrington, who died late last year, he told me how even his farewell party was broken up by gunmen. When he left Nigeria, the country was still a dictatorship. But when democratic rule was at last restored in 1999, Carrington and his wife returned for the celebrations. There, on a bright sunny day the governor of Lagos announced that the city was taking Louis Farrakhan’s name off the street signs in front of the embassy.

The street’s new name? Walter Carrington Crescent.

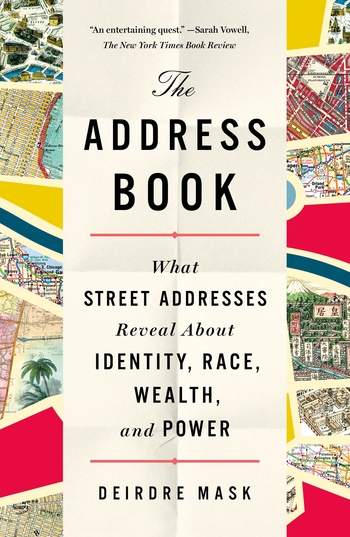

Deirdre Mask graduated from Harvard College summa cum laude, and attended University of Oxford before returning to Harvard for law school, where she was an editor of the Harvard Law Review. She completed a master’s in writing at the National University of Ireland.

The author of The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power, Deirdre’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Guardian. Originally from North Carolina, she has taught at Harvard and the London School of Economics. She lives with her husband and daughters in London.

Tags: Deirdre Mask, The Address Book, US history