By Tracy Nguyen

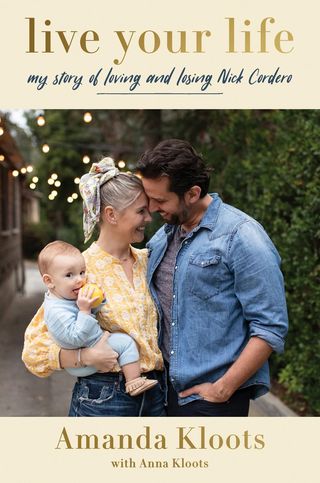

In mid-March of last year, with coronavirus cases spiking around the country, Amanda Kloots, a fitness instructor and online influencer, and her husband, the actor Nick Cordero, flew to Los Angeles from New York City. A few months prior, the couple had purchased a small three-bedroom fixer-upper in Laurel Canyon. While Kloots was reluctant to leave her life of 19 years in New York, where she had family and a thriving fitness business, Cordero had hopes of breaking into the music industry in L.A. In her new book, Live Your Life: My Story of Loving and Losing Nick Cordero, out this month from Harper, Kloots explains her mindset at the time. Like most of the country, she and Cordero thought the hysteria seemed “overhyped.” It is poignant to read her analyzing her errors in hindsight.

The couple landed in Los Angeles on March 17. The city announced its stay-at-home order two days later, on Kloots’s thirty-eighth birthday. The following morning, Cordero began complaining of exhaustion, but he didn’t have the cough, body aches, or fever commonly associated with the virus. Kloots recalls feeling “a little frustrated” by his lethargy—they had a nine-month-old baby; she had just launched an online subscription service for her classes—but she chalked it up to the massive changes of the moment. Cordero, an extrovert, was prone to depression, and the musical he was starring in, Rock of Ages, had just been canceled. But when Cordero fainted while changing their baby Elvis’s diaper—all 6 feet 5inches, 225 pounds of him crashing to the ground with a thud—Kloots realized something serious was going on and took him to urgent care, where he was told he likely had pneumonia. Days later, he was struggling to breathe. On the morning of March 30, Kloots dropped him off at the emergency room at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. “I had no idea,” she writes, “that that would be the last time I would ever see him as him.”

Cordero would spend 95 days in the hospital, most of them in a coma, before passing away due to complications from COVID at the age of 41. Kloots, meanwhile, chronicled the arduous, emotional ordeal on Instagram, where she maintains a prolific presence. During the two Zoom meetings we have together, I ask Kloots, who never tested positive for the virus, if she knows how or why her husband contracted such a severe case. After all, he was young and had no preexisting conditions. “We’ll never know how he got it or why he got it,” she tells me. “It doesn’t even make sense. I was around him. My parents were around him, my sister, our friends...and nobody else got it,” she says, shaking her head. “None of it makes sense. It never will.”

Courtesy of Amanda Kloots

Face to face, Kloots is warm, unguarded, and candid, with a demeanor that is fiercer and more blazingly intense than her sunny online persona would suggest. In Live Your Life, she notes that she is “type A to my core.” She tells me that her four siblings call her a “go-getter” and a “workaholic.” As she talks about her life, she is sometimes serious and emotional, her eyes welling up with tears. At other moments, she’s animated and funny, tilting her head dramatically and doing voices, like the former theater performer that she is. She has been in the ensemble casts of several Broadway musicals, including Good Vibrations, Follies, and Bullets Over Broadway, where she met Cordero in 2014, around the time her seven-year marriage to actor David Larsen was ending. She was also a Radio City Rockette and has run her own fitness business since 2016. “Amanda is always going,” her older brother Todd, 45, a software engineer who works for Slack, told me. “She’s ‘execute, execute, execute,’ ” he adds, comparing her to their father, a successful insurance salesman, now retired. (Her mother is a homemaker.)

We speak on a Wednesday afternoon in late February. Kloots, who is pretty in a classic way, is sitting in her dressing room on the CBS lot in Studio City, California, having just finished filming an episode of The Talk, which shoots four mornings a week. Kloots is one of five cohosts on the daytime talk show. She was hired in late November, nearly five months after her husband’s death. “Just to be able to go to work and talk to four other women is so important for me right now,” she says. Behind her hang three framed photographs: one of her holding Elvis, an adorable baby with wise eyes and wispy blond hair; another of a toddling Elvis in tiny overalls; and, in the middle, Cordero, hands in the pockets of his shorts, carrying Elvis, who is now two, in a Baby Björn on his chest.

Five days earlier, Kloots posted a photo on Instagram. She is sitting in a car at a drive-through vaccine clinic, wearing a denim mask with the name“Elvis” stitched in red. Outside the window, a National Guardsman can be seen administering the vaccine into her left upper arm. “I just got my COVID-19vaccine!” she wrote in the accompanying caption. “I went to a site and waited in my car until all of the appointments were over in hopes that they had any extra vaccines.... I have been terrified since Nick has passed, as a single mother, of getting this virus, and now I am one step closer to safety.”

At the time, the only people eligible for the vaccine in Los Angeles County, where Kloots lives, were health care workers or residents of long-term-care facilities. Kloots, a healthy 38-year-old leader of exercise classes who had no apparent preexisting conditions, clearly fell outside those criteria. Commenters accused her of white privilege, and of using her connections to jump the line and take a shot from someone who needed it more than she did. The site she visited was also on the Eastside of Los Angeles, a heavily Hispanic area disproportionately ravaged by the virus—though there’s no arguing that Kloots’s life was not ravaged by COVID, too. Kloots updated her original caption and took to her Instagram Stories to clarify, calling the response “vaccine shaming,” and explaining that she’d waited in line late at night for a leftover dose that would otherwise have been tossed. “I didn’t jump the fence, sneak into a tent, and shoot myself in the arm,” she says now. She describes getting vaccinated after losing her husband to COVID as “a full-circle feeling,” and says she was in the moment and posted without thinking.

The incident highlights not only how viperish the internet can be, but also how treacherous it can be to live one’s life very publicly on social media. Kloots has also been criticized for never stepping away from her public platform while her husband was sick, thus defying our ideas about how people should grieve. Her frequent posts on Instagram—memories of the couple’s relationship, heartbreaking updates on her husband’s condition and Baby Elvis’s milestones, plus clips and photos promoting her fitness classes and business ventures—reminded her followers that you can find yourself in truly awful circumstances and still find a way to, well, live your life. Hers is a thoroughly contemporary story, and not only because it’s about coronavirus. It is a tale of vulnerability, authenticity, and what it means to grieve in public, which, for better or worse, is how we grieve now, especially this year.

Courtesy of Amanda Kloots

Live Your Life, written by Kloots and her younger sister Anna (a writer and travel blogger working on a memoir of her own), elaborates on the history and memories that Instagram captions could not sufficiently detail. (The title comes from a song Cordero wrote that Kloots’s Instagram followers sang each day at 3 p.m. PST while he was hospitalized.) The book portrays Cordero as a serious artist, a lover of music and people, a devoted son and father, an excellent listener, and an impractical dreamer. Readers also get to see the pair’s relationship in all its humanness and complicated reality. Kloots tells us that they broke up twice before finally tying the knot in 2017. They fought about religion (she is Christian; he was not a believer) and what to name their baby (Elvis was her idea). They come off as well-paired opposites, like a couple in a rom-com. “Their imbalances kind of balanced each other out,” Anna says.“She would light a fire, and he would kind of tame her down. She was more conventional, whereas Nick was very avant-garde. It was a classic case of opposites attract.”

The book tunnels back to these memories while following Cordero’s harrowing medical odyssey chronologically. He was admitted to the ICU because his organs were oxygen-deprived. Doctors placed him in a medically induced coma and put him on a ventilator, an intervention that was readily used early on in the pandemic but eventually became a treatment of last resort because of the complications it can cause. Ten days into his stay, he got an infection and spiked a fever, which caused his heart to stop. At this point, the doctors put him on an ECMO, a machine that assists with heart and lung functioning. From there, Cordero experienced a cascade of medical problems: a blood clot in his right leg, which had to be amputated; internal bleeding; a lung infection; sepsis; acidosis. Four times, Kloots was told to rush to the hospital because her husband would be dead in a matter of hours.

Throughout the entire three-month ordeal, Kloots posted regularly on Instagram, where she has 654K followers, a number that has risen steadily in the last year. Kloots says that when she first starting sharing news about Nick being in the hospital, she thought he’d get better—she had no idea she’d be updating on his downturn and eventual death. Anna tells me that “there was never a doubt in our minds that he was not going to be okay.” Kloots also says she initially felt a duty to warn her followers that the virus didn’t exclusively affect old people.

“Things just kept happening, and I felt like, how can I not keep updating?”

In those early weeks of Cordero’s illness, when the pandemic was new and many people were glued to their screens, Kloots’s posts captured the public’s attention. She’s not sure the response would have been the same were people not “forced to stay at home and do nothing,” she tells me now. Tens of thousands liked each post. Thousands commented, including celebrities like Katie Couric and Selma Blair. Meanwhile, Cordero kept getting worse. And Kloots’s growing legion of followers—she calls them her “Instagram army”—became deeply invested. “Things just kept happening, and I felt like, How can I not keep updating, because now there are these people who are...clinging to this story?” She explains that she didn’t feel like she could be avidly online to promote and run her fitness classes and not tell the truth. “She kind of painted herself into a corner in a way,” says Zach Braff, who starred in Bullets Over Broadway with Cordero, and let Kloots live in his Laurel Canyon guesthouse while the bungalow the couple had bought was being renovated. “She didn’t want to let the community down, but there were days when she just wanted to disappear, you know?”

By Tracy Nguyen

TRACY NGUYEN

But Kloots didn’t disappear, not even in the days after Cordero died. “God has another angel in heaven now. My darling husband passed away this morning...I am in disbelief and hurting everywhere...,” she wrote in her post announcing his death, on July 5, 2020. The next day, she posted about the support of her family, writing, “In times of trauma, look for the silver linings.” And in the days and weeks that followed, she did just that, to the awe and admiration of many and the confusion of others. On July 18, she posted a video of herself, red-faced and smiling, executing a workout on all fours and advertising a jump rope she’d created for her class. “You’re so strong! Keep up the positivity [heart],” read a typical comment. Of course, some were not so supportive, suggesting she shouldn’t be smiling so soon after her husband’s death. “Oh, really?” she says now. “I should just be in my bed in tears then? Would that make you feel better?” When I watched the video, I saw a person, tired and a little puffy, trying to muscle through the pain and not entirely succeeding.

We meet over Zoom for a second time in early March. Kloots is once again in her dressing room. Wrapped in a pale gray robe, she peels and eats an orange as we talk. We discuss our culture’s rigid idea of what grief looks like—sobbing, breaking down, going to therapy—and the judgment that’s unleashed when people don’t adhere to this. She tells me that shortly after Cordero died, her three best friends came over one night and, in her words, “told me what I should do and what I shouldn’t do.” They suggested she go to therapy, get offline, and turn down a job she’d been offered: “ ‘Stop talking on social media. It’s not good for you.... If you do this, the world’s going to judge you.’ ” She says she was “taken aback,” though she knows her friends were only trying to protect her. “I just couldn’t believe that people were trying to tell you to do anything other than what you needed to do for yourself at that time. Yes, you might go right to therapy...but for me, it’s grabbing my jump rope and filming a workout.”

Kloots reiterates that she runs an on-line business, and when Cordero was hospitalized and out of work, perhaps forever, she realized that going offline was not an option. She recounts the criticism she received for promoting a Fourth of July sale on her fitness mats—the day before Cordero passed, as it turned out. “Oh my gosh, the shame,” she says. She went on Instagram Stories to address the negativity. “There’s a lot in my life that is uncertain right now,” she said. “I have a family. I have bills. I have no idea what Nick’s hospital bills are going to be. I have a mortgage. I have a car payment. I have a son. So I will work.” (Her friends also set up a GoFundMe that brought in more than a million dollars; the money helped with costs associated with Cordero’s illness.) Although the mix of promotional posts, medical updates, and grieving all together on the same page can occasionally be jarring, this is the way we live now, with all the facets of our lives on display. Yet Kloots also believes there was a frustrating double standard at work. “I wonder,” she says wryly, “if I was in the hospital and Nick was trying to provide for his family, would people be like, ‘What an exemplary father! What an amazing man trying to keep his business alive to support his family!’ ”

Kloots is clear that through it all, her belief in God was a source of great strength for her. Though she was raised Lutheran, her faith seems beyond the dictates of any particular religion, a seamless part of her life—she often mentions talking to God.“While it was happening, I noticed my faith getting stronger,” she says. Was it rocked by this tragedy? “Yes, of course,”she replies. “There were a lot of times where I was like, ‘Wow, God, this isn’t fair.’ And I could have easily just thrown my hands up and been like, ‘You don’t take a 41-year-old father for no reason!’ But that option sounds hopeless instead of hopeful. And I choose to be hopeful.”

Perhaps it is faith, then, that drives her ardent positivity. After all, what is optimism but a belief in the future? Optimism is Kloots’s brand: She posts a positive quote every morning, and has, with her sister, created “Hooray For” T-shirts that celebrate lovely parts of life, like birthdays and sisters. It can seem, at times, a tad forced. But her friends and family say she is a genuinely joyful person. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen her sad before this incident,” Braff says. And of course, no matter how authentic you are online, Instagram is only ever a snapshot of a moment. (In the book, she’s a lot more like the rest of us, occasionally popping a Xanax.) “There would be nights she would come home from the hospital, and...her mood would be completely destroyed by some news she got,” says her brother Todd. “Yes, she’s super positive. Yes, she’s superwoman. But she’s still human.”

Six months after Cordero’s death, having partly processed the experience by writing her book, Kloots felt ready to start therapy. “There’s just an innate part of me that is a fighter, I think,” she tells me, discussing one of her therapeutic epiphanies. “I don’t know where it comes from, but it’s there.” These days, she says, she’s not crying as much. “Every night, when I’m holding Elvis, before I put him down for sleep, I say our prayers. We always say goodnight to Dad. I cry every night, in that one second, and then it’s...then I wipe my tears and start cleaning up the kitchen.”

This article appears in the June/July 2021 issue of ELLE.

Amanda Fortini Amanda Fortini, has written for Elle and The New York Times, among other publications, and is the Beverly Rogers Fellow at the Black Mountain Institute at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io