For those of us with elderly parents, countless news broadcasts of bewildered residents cruelly exiled in care homes during this pandemic have been especially raw. Even so, I can’t be the only one who’s thought reflexively: “That will never be me.”

My friend Jolanta in Brooklyn has made that vow official. Put through quite the medical ringer herself, she tended to a difficult mother through a drawn-out decline. Not long ago, she declared to me fiercely that she’d no interest in living beyond the age of 80. Dead smart and not given to whimsy, Jolanta was already about 60, the very point at which old age starts to seem like something that might actually happen. I couldn’t help but wonder, should she indeed turn 80, will she take matters into her own hands – or not?

That, in a nutshell, is the genesis of my new novel, Should We Stay Or Should We Go. A nurse and GP in the NHS, Kay and Cyril Wilkinson have treated numerous patients eroded by ageing’s remorseless decay. After Kay’s father finally dies in a state of ruinous dementia, the couple are determined to avoid the same grim fate. Having concluded, like Jolanta, that beyond the knell of about eight decades life is all downhill, they make a pact: once they’ve both crossed that threshold on Kay’s 80th birthday, they’ll kill themselves. They’re still in their early 50s, and this prospect seems a long way off.

Whoosh, whoosh, we fast-forward their story, just as our time on this earth seems to race by before we know it in real life. It’s Kay’s 80th birthday. What do the couple do?

Despite the morbid premise, I’m hoping a playful parallel-universe structure makes Should We Stay improbably fun. The novel spins out a dozen alternative scenarios: one spouse goes through with it, the other doesn’t; they enter a Club Med care home, or their children section them into a Cuckoo’s Nest care home. Some chapters veer into speculative fiction – cryogenics, a cure for ageing. The point is to parse their dilemma. If they cut their lives artificially short, what delights might they miss out on, and what horrors might they escape? The novel considers what we all do, fleetingly, as the years advance: under what terms will we concede to keep living? Beyond what line does sticking around entail such suffering, diminishment, or humiliation that we’d rather call it quits?

Whether or not we feel like thinking about it now, many of us will turn to this issue in time. Elderly people have the highest global suicide rate of any demographic. Derek Humphry’s 1991 self-published how-to, Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying, became an unlikely New York Times bestseller for 18 weeks.

This is a personal matter for me, and not only because I’m already 64 myself. Both my parents are still alive – although in my mother’s case that may be stretching the meaning of the word. My father is 93; my mother turns 90 in July. Watching their old age progress has been mystifying, painful, and sometimes heartening.

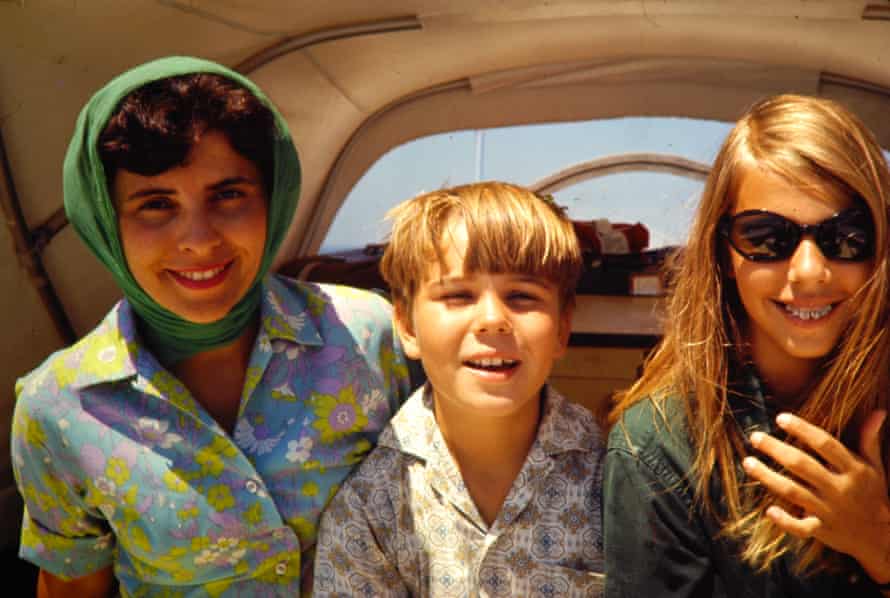

Class valedictorian in high school and college, my Iowan mother was a sharp cookie. She worked full-time as a researcher first for the Presbyterian church, then for the National Council of Churches. She played the cello and published two volumes of poetry. And it may mean too much to me, but my mother was a beautiful woman. A petite, brown-eyed brunette with a killer smile, she showed up with my forgotten bag lunch when I was in second grade, and the boy in the next desk gasped, “Your mom looks like a movie star!” She did. She looked like a movie star.

Whoosh, whoosh. After a massive stroke in 2015, my mother can’t walk. She can’t use her right hand. She’s incontinent. Her body has grown plump and soft. She can still talk – sort of. That is, she can form words, but rarely has much to say. Much of her scant discourse comprises polite vacuities. Asked how she is, she’ll say: “As well as can be expected.” Our sparse, formal phone conversations are full of silences.

When diagnosed with low-tension glaucoma in the 1990s, she was warned that, if she lived long enough, she’d go blind. She’s lived long enough. As of last year, this formerly voracious reader can’t discern a carry-out menu, nor can she lay eyes on her beloved husband. A television is a radio with lots of dead airtime. Mostly, she sits in her wheelchair, chin on chest. I’ve no idea what goes on in her head.

Her demeanour is pleasant. She’s undemanding and benevolent. She’s perfectly nice. But my real mother was not nice! Our relationship was often prickly. Real Mother was prone to sudden, unexpected bursts of resentment. Real Mother was a touchy, complicated woman who banged about the kitchen in unexplained white rages while giving us all the “silent treatment”. I’d trade all that niceness for one more night of crashing silverware in a heartbeat.

If Real Mother could see herself now, would she wish her elderly self were dead? Even Fraudulent Mother often asserts that she’s ready to die. This may be the most content-rich statement I’ve heard from her since 2015: “I don’t want to die, but I need to die.” In most meaningful senses, my mother is no longer here, but I’ve been cheated even of my own bereavement.

My Virginian father had a long, distinguished theological career culminating in 16 years as president of the storied Union Theological Seminary in New York. In his day a handsome, ambitious, vigorous man (he taught me to play tennis), possessed of a towering ego, he’s also published a stack of books. On retirement, he declared vehemently that he did not want his savings frittered on end-of-life care.

Whoosh, whoosh. Steadily, his savings are frittered on end-of-life care. Since my mother’s stroke, my parents have hired full-time live-in help. Like so many elderly pandemic shut-ins, they’ve barely left the apartment in more than a year. My father is still – pretty much – #cogent, but with odd lapses; someone seems to have put a cigarette out on the part of his brain that stores numbers. He announced three times not long ago that this summer he’ll have been married to my mother “for 268 years!” But we continue to conduct engaging conversations, and in the past month he’s finally stopped railing against Donald Trump.

His body, however, is failing. He can no longer bear his own weight. A recent infection mandated the amputation of one of his toes. His digestive system keeps packing in, and subsequent avoidance of food has made him gaunt. It’s disconcerting to see such a powerhouse contained in a vessel so weak.

I noted that some aspects of this parental passion play have been “heartening”. At 93, my father is still fundamentally himself. He has accommodated the steady shrinking of his life – no more New York Philharmonic or Metropolitan Opera – with resigned grace. Pre-pandemic, he resisted a mobility scooter at first, but rapidly reconciled to the perceived demotion, zooming the Upper West Side with gusto. These days, he accedes to his faithful carer’s necessary involvement in his intimate bodily functions without a fuss, for he’s not hung up on younger people’s strangely bathroomy version of what constitutes “dignity”. My father still has dignity, or the kind that counts. He remains in the grip of an astonishing life force. He’s proud of his accomplishments and won’t let anyone forget them. Despite the imposed compromises of advanced age – compromises that, in my naivety, I imagine would be unacceptable to me – my father clings ferociously to survival. Glimpsing this future, his younger incarnation would be sobered, but lifelong self-regard would preclude his ever vowing that he’d rather be dead.

We enter into an implicit contract with ourselves regarding what we’re willing to put up with in order to stay in the game, and when we’re younger the conditions under which we’ll submit to continued existence can be strict. Maybe it sounds ludicrous, but for much of my life I’d have told you that a future in which I could no longer play tennis was out of the question. I’m an intensely physical person, and the notion of sitting indefinitely in my mother’s wheelchair strikes me as intolerable. Faced with some mildly disagreeable prospect, I’m given to tossing off carelessly: “I’d rather kill myself!”

Yet during one short period I made that declaration in earnest. For this implicit contract with ourselves must be at its most sincere in respect to physical pain. For five days last summer, I experienced a degree of agony that, had it endured as a condition of my existence, I’d have headed for the ultimate exit to make it stop. (There’s nothing worse than nerve pain. Fellow sufferers know what I mean.) Dial up the pain high enough, and five seconds passes like a week. Above a certain subjective threshold of torment – the limit must be particular to the person – life is not worth living. It fails a primitive cost-benefit analysis. Being is purchased at too high a price, and pain is so despoiling that existence compensates with little, if any, reward.

That’s why the cause of legal assisted dying is usually taken up by people who are physically suffering, often from a condition that will only get worse. Although physician-assisted death is now permitted in half a dozen countries, it’s still illegal in the UK, where a doctor who helps someone to die can get up to 14 years in prison. Yet the MP Andrew Mitchell, co-chair of the all-party parliamentary group for choice at the end of life, believes British laws on assisted dying could be liberalised within this parliament. Already under-prosecution is rife, and in plenty of grey-area instances, fading patients are quietly allowed to die or given extra pain meds that speed the process.

Katie Engelhart’s compelling 2021 book, The Inevitable, is about people determined to exercise control over their own deaths. While some of the author’s interviewees are aiming for Dignitas in Switzerland (where locals allude drily to the “suicide tourism industry”), to which 475 Britons have travelled to end their lives this century, the majority are taking death into their own hands, regardless of the law. Yet most people who ask to die, Engelhart reports, are “not in terrible pain, or even afraid of future pain”. Instead, they want to die at a time of their choosing for “existential reasons”. They fear “losing autonomy”, “loss of dignity”, and “losing control of bodily functions”. Indeed, the latter two anxieties are often synonymous: “A lot of people I interviewed equated dignity precisely with sphincter control.” (In one hospital survey, more than two-thirds of patients over 60 considered double incontinence “as bad as or worse than death”.) Strikingly, for me, one entirely healthy subject announces: “I’ll be 80 in four years’ time and 80 is the time to die” – just like my fictional Wilkinsons. Four years later, the woman overdoses peacefully on barbiturates, right according to plan.

Most of all, Engelhart’s subjects dread losing their identity to dementia. Yet nipping dementia in the bud requires acting before the disease has advanced – thereby sacrificing a period of unknowable duration when you might have been nearly yourself. That is, only giving up some good life guarantees being spared bad life. I’ve another friend in the US whose droll, beguiling husband was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s last year at only 67. (He’d played a lot of American football.) With his wife’s sorrowful blessing, while still of broadly sound mind, the talented architect ended his life at Dignitas a few months later. That took stupendous commitment and courage. Most of us couldn’t do it.

In the 2014 film Still Alice, Julianne Moore plays a linguistics professor diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s at 50. She leaves a list of simple questions for her future self, along with the location of the sleeping tablets if she draws a blank. But when Alice fails her own competency test and finds the tablets, she gets distracted and forgets what she was about to do. She’s missed her chance to exert control. In dementia circles, this is known as the “five-minutes-to-12 syndrome”. The temptation is to hang on until it’s too late, and the opportunity to exercise agency over the end of your life has passed.

It’s difficult to kill yourself painlessly – one reason most suicides fail. We produce drugs to put down suffering animals, but we don’t design drugs to kill people. Thus a slogan of the right-to-die movement runs: “I would rather die like a dog.” Lethal drugs are hard to come by and can be confiscated by customs or the police. In Should We Stay, Cyril readily acquires “an effective medical solution”, stored in an upper corner of the couple’s refrigerator for decades, only because he has prescribing privileges as a GP. The rest of us who live where assisted dying remains illegal are obliged to order underground books and commence furtive subterfuges to secure a stash.

Where the practice is permitted, qualifications for assisted dying vary, often involving a terminal diagnosis and a prognosis of death within six months. But more interesting to me is our private stipulations. In what circumstances do we personally regard life as unbearable?

While still on the cusp of this negotiation, I imagine that the journey from our often-hale 60s to the life of the “old-old” – my parents – entails getting stuck on the “bargaining” phase of the five classic stages of grief:

All right, maybe insisting that if I can’t play tennis I’ll dive off Blackfriars Bridge is unreasonable. Obviously, the number of press-ups I can do will gradually drop. No press-ups at all, you say? Fine. Bit of a relief, actually: no press-ups, good riddance. At least I can still cycle. No? You’re kidding me. I’ve cycled everywhere since I was eight! It’s part of who I am! OK, OK. They say walking is the best exercise anyway… Oh. Too painful? I can barely make it to the shops? Well, that’s what they make online delivery services for. Gosh, I just went through three solid days unable to remember the name of my best friend in primary school. Happens at any age; one of those “blocked neural pathways”. Came to me in due course. But it’s harder to explain why I just found a pair of socks chilling in my vegetable drawer.

I always thought I couldn’t live without my husband, but apparently I can, though some days I suffer under a cloud of desolation, like a low-pressure weather system that won’t budge. It’s at least a comfort to remain in the home we shared. What do you mean my relatives have expressed “concern”? What’s to be so bleeding concerned about? I do, too, wash! Well. After a fashion. See, I hate having to sit on that plastic chair in the shower. Nevertheless, I promised myself that I’ll never submit to a care home. I won’t, I won’t! Reluctantly, I concede my niece’s point: I forgot about the chicken. Without her impromptu visit, that grease fire could have proved my funeral pyre. Besides, I’m not as special as I imagine. Everyone thinks they’ll never submit to a care home – and then they do, and so do I. At least the staff are kind. The other residents aren’t all my cup of tea, but it’s a relief to talk to anyone. Bland institutional meals still punctuate the day. I used to love cooking – but only when fixing dinner for two. Nappies? You get over the embarrassment, and the carers are brisk and professional. No one here knows who I am, what I was, all the books I wrote. But that Lionel Shriver is one more thing I’ve learned to forego.

We make these compromises by degrees. Legalise assisted suicide in Britain and only a tiny minority will avail themselves of it, because most of us will put up with anything rather than die. My father is apt to put up with anything. He’s not checking out of Hotel Terra Firma unless he’s actively ejected by the management.

I fancy Katie Engelhart’s characterisation of a chosen death as “an authorial act”, and I’ve never cared for stories that end on ellipses. Thus I desperately don’t want to end up like my mother, who on my brother’s latest visit no longer recognised him. She’s grown, he said, “unreachable”. My mother’s dazzling, articulate younger iteration would recoil from a version of herself that is unseeing, inert, and unresponsive. Yet she long ago signed a living will, as I have. Had she kept an “effective medical solution” at the back of her fridge, after that blitzkrieg of a stroke she’d have lacked the self-possession to take the tablets. Genetically, I will have inherited many of her medical vulnerabilities. So how will I not end up like my mother?

I have no idea.

Should We Stay Or Should We Go by Lionel Shriver is published on 10 June by the Borough Press (£18.99). To support the Guardian preorder your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply