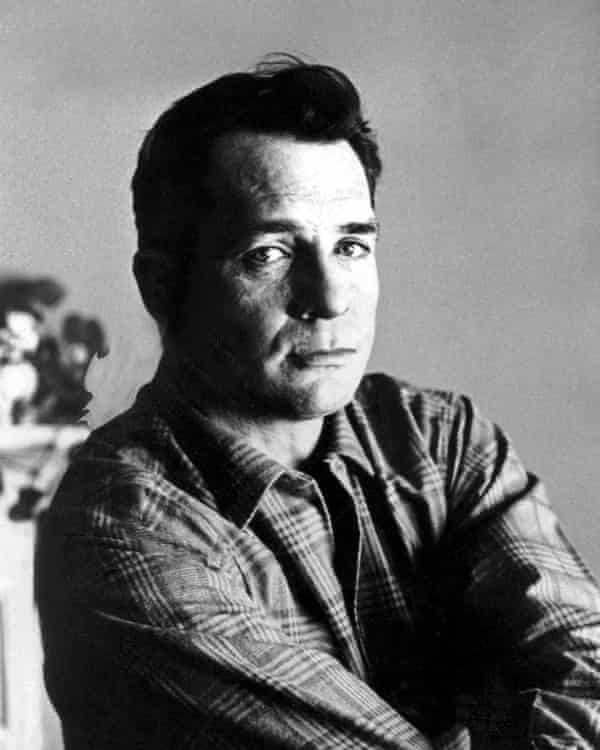

The King of the Beats, Jack Kerouac, was renowned for laying bare his life in more than a dozen roman a clef novels, his most famous being On the Road, which documented the birth, rise and final days of an enduring counterculture.

But while larger-than-life characters such as Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Neal Cassady wandered in and out of Kerouac’s works under a variety of pseudonyms, one important figure in the writer’s life is conspicuously absent: his daughter, Jan Kerouac, who died 25 years ago this week.

Jan was pretty much erased from the Kerouac legend even before she was born. She met her father only twice before he died in 1969, and in the quarter of a century between his death and her own, she had to fight for recognition and monetary support from his estate.

But Jan wasn’t only the secret child of a famous author. She was a writer in her own right, with two published novels and a third one almost finished when she died at the age of 44, following years of drinking, drug abuse and kidney failure.

Jack had a complicated relationship with women. He was married three times: in 1946 to art student Edie Parker, which lasted less than two years; then in 1950 for eight months to Joan Haverty, Jan’s mother; and in 1966, three years before his death, to Stella Sampas, the sister of a childhood friend from his hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts. But the freewheeling godfather of the Beats, who espoused a dream of mystical hobo liberty, never quite managed to cut the apron strings. It was his mother Gabrielle, says Gerald Nicosia, his biographer and a longtime friend of Jan’s, who fed his lifelong estrangement from his only child.

Nicosia first met Jan in 1978 when he was researching his Kerouac biography Memory Babe. She had inherited her father’s wanderlust and was living a life on the road, sofa-surfing around the US. Nicosia tracked her down to Russian Hill in San Francisco, where she was crashing with a friend. From the moment he clapped eyes on her, Nicosia knew she couldn’t be anyone else’s daughter – “that black hair and those blue eyes” – but it wasn’t until Jan was 10, having grown up in poverty, that Kerouac began to pay maintenance cheques of $52 a month, after a blood test confirmed his paternity.

Nicosia says Kerouac took so long to recognise Jan because of his mother’s beliefs: “Gabrielle was a very devout Catholic and when Joan got pregnant with Jan, Jack asked her to get an abortion because he wasn’t making any money and didn’t think he could support a kid. His first book, The Town and the City, had sold 400 copies and he couldn’t get anyone to even look at On the Road at that point.” But Joan didn’t want an abortion – they were also illegal when Jan was born, in February 1952 – and Kerouac’s mother had told him that he could never leave a pregnant woman.

So he claimed Jan wasn’t his child. “That was his way of placating his mother and being able to leave Joan,” says Nicosia. “The trouble was, he was stuck with that lie for the rest of his life. He could never come back and say, actually, she is my daughter. Jack’s mother outlived him, so he always had to deny it.”

Jan met her father for the first time at the paternity test. She would meet with him once more, later in his life, when he lived in Florida, and had one conversation with him on the phone. Nicosia says that privately, Kerouac would talk about Jan to fellow Beat figures such as John Clellon Holmes, and he carried a photograph of her in his wallet, “hidden beneath some other pictures”.

Growing up with a famous but absent father was difficult for Jan. As she began to move into literary circles, she met her father’s friends such as Ginsberg and others who knew more about her father than she did, which she found frustrating. She began to write: her first book, a raw, autobiographical novel called Baby Driver, was published in 1981 and uncompromisingly detailed her life with drink, drugs and a string of unsuitable men. If Kerouac sometimes put a spiritual gloss on poverty and life on the edge, his daughter offered an unflinching vision. A follow-up novel, Trainsong, followed in 1988. She was working on a third, Parrot Fever, when she died in 1996 at the age of 44 – just three years younger than her father was when he died of drink-related illnesses.

Jan’s last years were taken up with a series of legal actions to try to wrest control of her father’s works and archives from the Kerouac estate, run by the family of his third wife Stella Sampas. Nicosia, who acted as her executor for three years after her death, thinks the estate has effectively tried to erase Jan from the record of the writer’s life. “There’s an exhibition in Lowell that runs to three rooms and there’s not a single photo of Jan,” he says. (The Kerouac estate has not responded to requests for comment.)

Parrot Fever was never finished, though Nicosia and others worked on editing Jan’s drafts together into a completed manuscript. Baby Driver and Trainsong have fallen out of print. Nicosia would like, with celebrations of the centenary of Kerouac’s birth planned for next year, to see more recognition given to Jan, both as Jack’s daughter and as a writer in her own regard.

Had she lived, she would have been 69 now. Nicosia believes she could have become “a really great and powerful writer”.

Did Jan become a writer because of Jack? “I think so,” says Nicosia. “I think that she couldn’t find her father in the outside world, and then he was gone and dead, so the only place she could find him was inside herself. I think in many ways she tried to become him, with the rambling and the travelling with no money, the alcohol and the drugs and the sexual wildness. I think in some ways she was trying to find her father by becoming her father.”

It seems tragic that father and daughter were so obviously alike, and were on similarly destructive trajectories, and yet they were estranged. It’s hard not to imagine how their lives could have been different if that hadn’t been the case. “It would have changed them both, I think,” Nicosia says. “For Jan, she would have had her father with her when she was growing up. And Jack basically died a depressed and lonely alcoholic. If he’d had a brilliant, beautiful, loving daughter … you know, how might that have changed his whole life?”