As the world heats up and sea levels rise, communities in the U.S. could spend more than $400 billion on seawalls to try to hold the ocean back over the next couple of decades. But there’s a catch: Building a seawall in one area can often mean that flooding gets even worse in another neighborhood or city nearby.

“Basically, the water has to flow somewhere,” says Anne Guerry, chief strategy officer and lead scientist at Stanford University’s Natural Capital Project. Guerry is also coauthor of a new paper in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that models how seawalls in the Bay Area could lead to unintended impacts. “What we found is that it ends up flowing into other communities, making their flooding much worse,” she says.

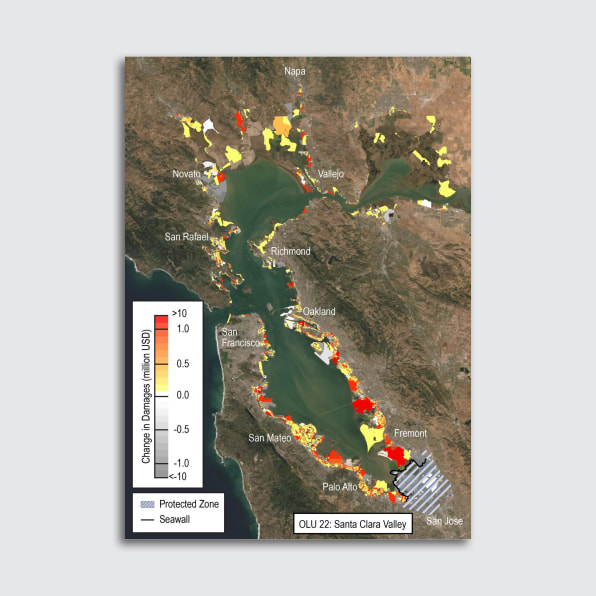

Researchers used complex hydrological and economic models to map out what could happen along the shoreline in the Bay Area, which faces nearly seven feet of sea level rise this century, if long seawalls were built in various locations. “We divided the shoreline into chunks, and modeled changes in flood depths and economic damages along all other chunks of the shoreline that will result from building a great big seawall along each shoreline chunk in turn,” Guerry explains. A seawall built in the San Jose region, for example, could add $723 million in flood damages to other communities in the area after just one high tide.

Natural flood protection can often have a better result, such as “allowing low-lying areas to act as a sponge for flood waters,” she says. “They can act as overflow zones.” That might mean restoring marshes or oyster beds, or simply including parks or other open space where intermittent flooding will cause less damage. When the researchers looked at a highway in Napa and Sonoma counties that is now at risk of flooding, they found that building a higher embankment would make floods worse in cities as far south as San Jose. Rebuilding a low causeway that would let the water be reabsorbed naturally, on the other hand, would avoid that problem.

In some locations along the shoreline, a seawall might not cause major problems elsewhere. An individual project might also not seem to have significant impact. But without modeling the effects and understanding how they interact with multiple other projects in an area, it’s hard to know where heavily engineered protection makes sense. Cities will have to work together to plan infrastructure, something that isn’t happening now. It’s critical for equity: In many areas, both in the U.S. and around the world, low-income communities are already living in areas that are more likely to flood. If richer neighborhoods can afford to build seawalls nearby, the situation could get even more dire. “In some cases, building a seawall might directly protect wealthier communities while leaving poor neighboring communities at higher risk of flooding,” Guerry says.

“Every community around the Bay is hydrologically connected,” she says. “So it makes sense for our adaptation plans to be connected as well.”