The cheaply produced, easily digestible stories were once the perfect cover for state-produced propaganda.

In World War II and the Cold War, government agencies recognized how powerful comic books were and exploited the medium to sell the idea of America across the world. Although by 1954, legislators had become alarmed by the violent and sexual content of comics, and stepped in to force the industry to self-regulate—see: the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, the Comics Code—other parts of the federal government saw potential in the medium’s reach and appeal, and exploited it. The Writers’ War Board and, later, agencies within the State Department found ways to use comic books to sway hearts and minds across the globe toward the objectives of the American government.

This is the argument of a new history of government involvement in the production of pro-American comic books, Pulp Empire: The Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism, written by Paul S. Hirsch. I asked Hirsch to walk me through a show and tell of a few of the most telling government-endorsed and government-created images from his book.

Paul S. Hirsch: During World War II, comic books were prevalent to a degree that it’s almost impossible to imagine now. They were selling close to a billion copies a year—and they were selling them all over the world. Not just in the United States, where they were certainly consumed ravenously on the homefront. The government viewed comics as essential material, like tobacco—something that that soldiers needed to function in the field. So, they were shipping comics everywhere that American soldiers were.

The Writers’ War Board was an organization staffed by writers and artists who were big in popular culture at the time. And they were not paid—on paper, anyway. The board was very consciously trying not to be like German and Japanese state-sponsored propaganda arms. That’s one of the main reasons they self-describe as volunteers, and why the heads of the board were culled from American popular culture, instead of from the government.

The board secretly got all its funding from the Office of War Information, which was a larger propaganda agency during the war. But on its face, the board was a volunteer agency helping fight fascism through popular culture. So they didn’t have any final say over what publishers printed—they were not a censorship organization. That said, the publishers had a lot of compelling reasons to cooperate with the board. So, if the board told them not to print something, at least from my reading of the documents, it seems like in most cases, it wasn’t printed.

The board had pretty frequent communication with the major publishers cooperating, and they knew that if they were going to print anti-Japanese stories, or stories about Nazi atrocities, they may want to submit it to the board, and they may actually ask the board for assistance scripting it. In some cases, the board would go to the companies and tell them, Please write a story with these characters and this plot. And when that happened, the publishers would submit drafts for editing.

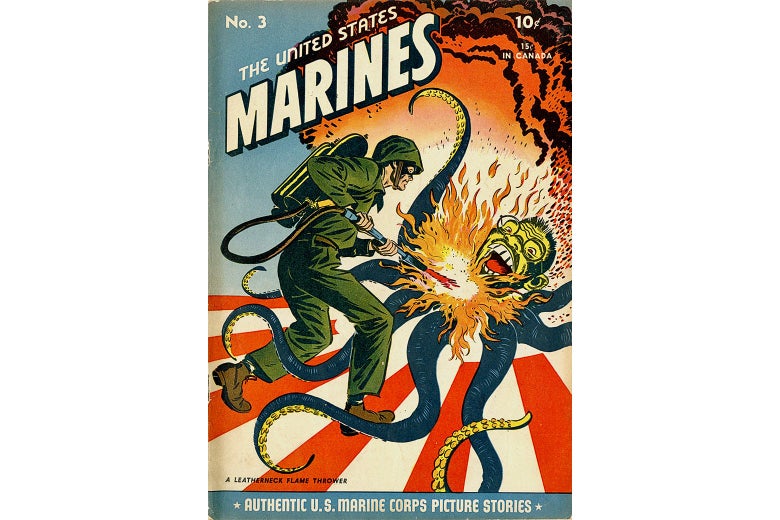

A big part of the program to co-opt comic books was to get publishers to make very specific images of Japanese characters. Above all, they wanted to make sure that there’s no such thing as a “good Japanese person” in comics. There was a story submitted to the Writers’ War Board by one of the big companies, and in it, there is an anti-fascist resistance in Japan. There’s a woman who is presented as anti-fascist, and pro-democracy, and she’s fighting for democracy in Japan. And the company submitted this to the Writers’ War Board, and immediately the board says, No, there’s no such thing as a good Japanese person.

This picture we’re looking at was made by a company trying to appease the board by showing Japanese soldiers as something totally deserving of extermination. I had always imagined that this was an individual choice on an artist’s or writer’s part, so what really melted my brain, going through the Writers’ War Board documents, was understanding that this was a state-sanctioned covert program to shape popular perceptions, and it was done very specifically, with guidelines for how Japanese and German people were to be represented.

This comic, which has this almost indescribably vicious anti-Japanese racism, did break with the board’s policies in one way, on the cover. The board actually encouraged publishers to present Japanese characters as people—not as subhuman, or as animals. They wanted American soldiers and civilians to understand that Japanese people were an extremely powerful, devoted, and tough-to-beat enemy, and portraying them as subhuman or as animals was, they thought, a disservice that would confuse Americans about the seriousness of the threat they faced.

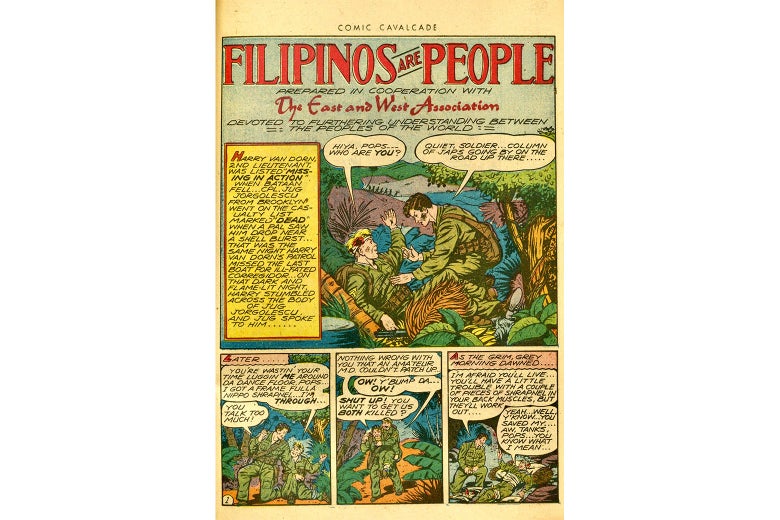

We’ve talked about the way the Writers’ War Board laid out how characters should be represented, but they also had very specific instructions about how to represent U.S. allies. They understand that Americans are going to be confused, being told to exterminate one variety of Asian people at the same time that the U.S. is allied with other Asian countries, like the Philippines and China.

This story is an example of a board-sanctioned effort to get Americans to sympathize with some of their allies of color. The board put less effort into promoting tolerance—I’d say, dramatically less effort—than into promoting hatred. But there was some. You can tell from the plaintive tone of this title how low the bar was!

They also wanted to promote, however mildly, equality on the homefront between races, not out of any sense of altruism, but to make sure that wartime production was not disrupted by riots, and that dissension in the United States wouldn’t offer propaganda opportunities to Germany and Japan.

The rest of this story includes Japanese and Filipino characters sharing space in comic book panels, and they are virtually indistinguishable. It’s very visually haphazard, and the words on the page clash with the visuals on the page.

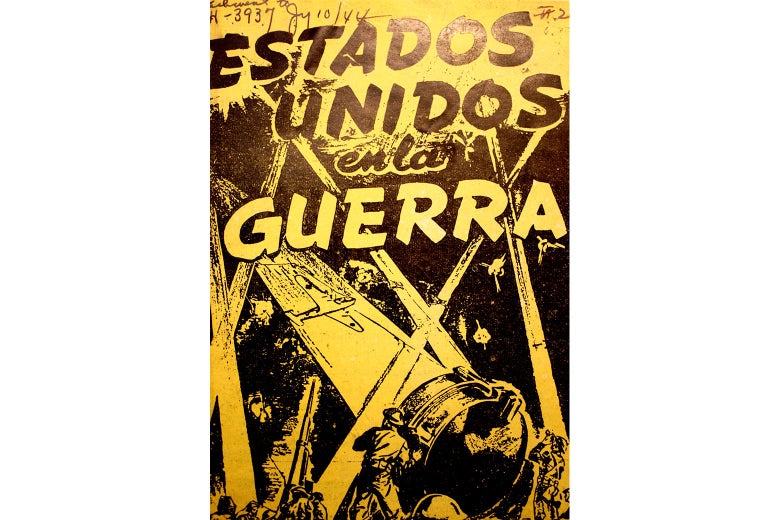

This is the cover of a comic book published by the Office for Inter-American Affairs, or the OIAA. This is another wartime organization taking a different approach to comic books and propaganda. The WWB was embedding its stories inside commercial comic books, publishing them in English, and using them primarily for American readers, whether at home or abroad. The OIAA published comics in the languages of the countries where they were distributed, throughout South and Central America.

These are overtly propagandistic comic books, not stories embedded in commercial books, but complete comics unto themselves. This is an example of a comic distributed throughout Latin America in an effort to convince audiences there that it’s worthwhile to join the fight against fascism—that they shouldn’t be neutral.

This is more cheaply done, they’re often not in color in the interior; you can see this cover is just one color, just yellow beneath black. There’s really not effort to disguise who’s publishing this. Picking up this comic, you have no question where it’s from and the reason why it’s been published.

There are a few specific reasons why government agencies decided to go toward making comic books. The first was: They’re cheap to produce. The second was: They’re portable. You can shift huge quantities of comic books around the world without taking up much space. The third, in the case of stories published by the Writers’ War Board that didn’t identify themselves as coming from the government, is that the comic provides a perfect cover for propaganda. They look like such trash; people reading them are very unlikely to think that the government had anything to with producing them. The sleazy advertisements in comics, the poor printing, the general cheapness of the object itself—they all provided the perfect cover for state-produced propaganda.

And the fourth, really relevant to this comic and to other comics published during the Cold War for propaganda purposes abroad, is that there’s a prevailing belief among federal policymakers that comics are comprehensible to everyone, and particularly to uneducated, nonwhite audiences. There’s a prevailing prejudice amongst these policymakers and propagandists that throughout the global South, people are not sufficiently sophisticated to understand books. They don’t have the infrastructure to be shown moving pictures.

So the traditional propaganda avenues are closed off, and comics, they think, are the perfect alternative to that. They can be provided either cheap or free; they can be airdropped. They’re durable; they can be smuggled into places. They can be easily hidden, and the belief is that anyone can understand them, whether you’re a 6-year-old in Ghana or an 80-year-old in Guatemala—even if you’re illiterate. And the belief is also that not only will you understand it, but you will get the intended message, and be persuaded. Now, there was a total lack of scientific evidence that people pulled the intended message out of the comics—but nobody involved in producing them cared about that very much.

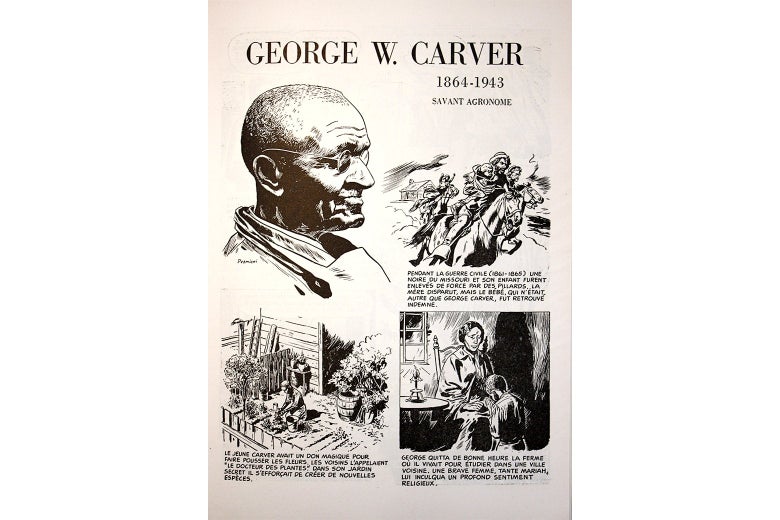

This one is a creation of the State Department’s, during the Cold War. This one interests me, because the U.S. government really wanted to keep comic books away from Western Europe during that time. They thought comic books were the perfect propaganda vehicle for the global South and the decolonizing world, but that comic books were an embarrassment among white audiences in Western Europe. So this was one of these rare comics that was intended for distribution in areas including Western Europe.

There was this fear in Europe that American comic books, along with American culture, were washing over the globe. Wherever American soldiers travel, wherever American tourists travel, they leave comic books behind them. And after World War II, since there was no censorship of American comics until 1954, the comics those people were bringing were free to be transgressive, violent, sexual, racist. Crime, romance, and horror comics hit the top of the sales chart, and these can be deeply problematic in a lot of ways. It’s this combination of violence, sexuality, and racism that could cause huge problems for the U.S. government abroad, particularly in Western Europe, which is the place where America most wants to appear cultured and sophisticated.

The State Department was aware of all this and trying to counteract it; this Eight Great Americans comic book is one of the things they tried. It was published in probably a dozen languages and was meant to show Western European leaders in particular that the United States was a very racially tolerant, socially inclusive society. This comic is physically different than most propaganda comics made by the United States; it’s printed on heavy paper stock, and the artwork is of a dramatically higher quality.

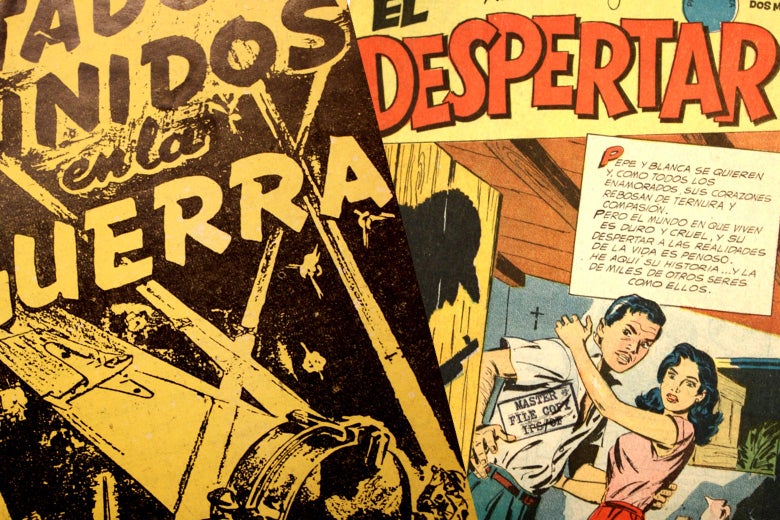

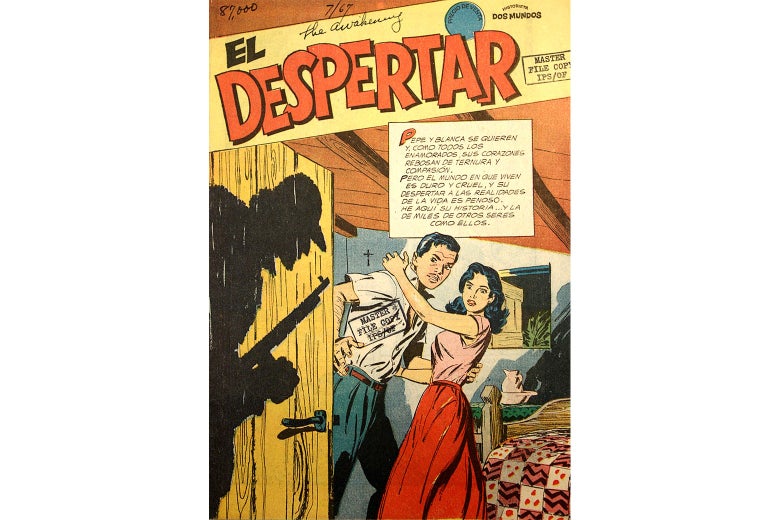

This one’s tough to date. As far as I can tell, it’s from the early 1960s through the late 1960s. I think it was used as part of something called Operation Mongoose, a multifaceted campaign to overturn Castro in Cuba, which began in late 1961 after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. My understanding is that this was part of perhaps a dozen titles that were printed in large numbers as part of Operation Mongoose.

I think this because I read discussions in State Department documents that have been declassified that decreed that the U.S. Information Agency, which was part of the State Department, should produce nonattributable comics to be distributed, throughout Latin America. They would be distributed in a remarkable series of ways: They were airdropped; they were smuggled; they were given to religious leaders to slip into prayer books; they were given to supermarket employees, who would sneak them into shoppers’ bags. And one document I came across said that in July 1962, the USIA recorded that it currently had in production or had already distributed 5 million copies of six anti-Castro comic books. … So that’s my basic reason for believing this one was part of Operation Mongoose.

This comic has the story of two friends who fought together to overthrow the former dictator, Fulgencio Batista, but their friendship crumbles because one of them becomes a communist, and prioritizes Castro and revolution over his friends and family, while the other feels that they have been betrayed by the revolution and decides to flee. He says he will come back, to organize counterrevolution, with others like him.

The State Department was overwhelmingly the producer of comics approved for propaganda purposes during the Cold War. As far as I can tell, what brings this to an end is Vietnam. The State Department was distributing comics in Vietnam as early as 1964, seeing it as no different from other parts of the decolonizing world, and so a target for comic book propaganda. But as the United States ramped up the war in Vietnam, it became increasingly difficult to present the U.S. to audiences in the decolonizing world as a sophisticated, enlightened place that encouraged racial tolerance. It’s because of that, I believe, that the comic book propaganda program began to wane.

American comic books spread around the world during the 20th century, and they infiltrated every aspect of cultural life—not just in the U.S., but in many countries. And these 20th century comics still exist as ghosts among us. All the excitement, trauma, rage they generated—they’re not dead. Contemporary global perception of the United States emerges from memory as much as experiences. And that’s the impact these comics still have.