The Historians Are Fighting

Inside the profession, the battle over the 1619 Project continues.

People who don’t obsessively follow the ins and outs of the American history profession may have missed the news that, last Saturday, two leading historians of the founding period, Woody Holton, McCausland professor of history at the University of South Carolina, and Gordon Wood, Alva O. Way university professor and professor of history emeritus at Brown University, had a rowdy public throwdown over the role of slavery and racism in the U.S. founding, among other things. The debate, as it was billed, was hosted by the Massachusetts Historical Society for a live audience and streamed live on the internet. It devolved into a long, loud sequence when a revved-up, happy-warrior Holton started fast-talking over and relentlessly haranguing a clearly irritated Wood, who was reduced to defensive sputtering.

Subscribe to the Slatest Newsletter

A daily email update of the stories you need to read right now.

Given the tone of today’s public affairs TV, that might not sound like much. For those accustomed to the sometimes strained collegiality of more typical academic panels, the moment was memorable, in part for intensifying a recent trend in modes of dispute among scholars of the founding period. The August 2019 publication of the New York Times’ 1619 Project has changed everything—and, some might argue, not for the better. Battles among scholars have typically been waged in the pages of peer-reviewed journals that most members of the public never see. For generations, consensus achieved in the remotest groves of academe has trickled down to public consciousness through curricula, textbooks, trade publishing, museum exhibits, and other highly curated channels. Venerable traditions of academic history haven’t usually included mano a mano contests on fine points of interpretation, held for the excitement of the baying crowd or, as in this case, the edification of decorous history buffs.

An immediate contingency, for Holton and Wood: They’ve both recently published books—Liberty Is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution and Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution, respectively—and are making the promotional rounds. These new books build on significant careers. Wood is a lion of the “republican synthesis” interpretation of the founding, in which the multitude of social conflicts that marked the period are eventually resolved, if roughly, in a small-capitalist, anti-deferential ethos emerging in the Jackson era; the American Revolution thus represents world-changing, even human-consciousness-changing progress and should, for all of its flaws, be celebrated as such. Holton, a feisty inheritor of the “bottom-up” school of founding studies, has cracked open the frame adopted by Wood and others, asserting and documenting the multitude of contributions to the Revolution of free and enslaved Black people, Indigenous people, women, artisans, small farmers, laborers, and others traditionally left out of the synthesis, whose elitism Holton’s work criticizes.

The debate got off to a pretty rollicking start. Wood called Holton’s book “very malproportioned” and took issue with its focus and premises (he had also blurbed it, which might tell you something about blurbs); Holton, illustrating colonists’ ideas about their place in the empire before 1775, sang a line from Barbra Streisand’s “The Way We Were.” When Wood claimed Thomas Jefferson had no intention of exterminating Native nations, Holton pounced, quoting a letter in which Jefferson said he did intend extermination. (For some of us, at least, this qualifies as fun stuff.)

The moderator, historian and Massachusetts Historical Society president Catherine Allgor, then focused the discussion. These two historians had recently come at explicit odds, she noted. In July of 2021, a group of historians, including Wood, published an open letter disputing Holton’s claim, made in a Washington Post op-ed, that a desire to protect the institution of slavery was central to the colonists’ decision to rebel against Britain.

That, of course, is also a claim of the 1619 Project. In December of 2019, Wood joined in the crafting of an open letter to the editor of the New York Times Magazine (there’s a lot of open letter–writing going on), objecting to the project’s claim that protecting slavery served as a cause of the Revolution and asking for various editorial corrections. While Holton’s Post op-ed didn’t mention the 1619 Project, in many public statements, mostly on Twitter, he’s been explicit about his intention to defend statements regarding the centrality of slavery to the American decision to rebel, as made by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the project’s editor, in her lead article. On his Twitter, Holton has associated Liberty Is Sweet both with Hannah-Jones’ essay and with the imminently forthcoming book The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. As Allgor reminded the two pugilists at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the 1619 Project and its cultural impact provide key context for their contest.

So were Holton and Wood fighting over the role of slavery in causing the American Revolution? Or were they fighting over the relative validity of the 1619 Project, and the impact of both the project and Hannah-Jones’ work in general, on public understandings of American history? Or are those fights now more or less the same fight?

The questions arise amid ongoing political and educational controversies swirling around the project, and around Hannah-Jones, in which historians are closely involved. Right-wing state legislatures and school boards are scoring points with a political base by loudly shutting out of history curricula not only the 1619 Project but also any realistic discussion of American racism. Responding to blatant political pressure, the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media denied Hannah-Jones tenure, in a position for which tenure had always been presumed. As Allgor noted during the Holton-Wood debate, the Middlesex School, in Concord, Massachusetts, had just canceled a scheduled Hannah-Jones appearance. It may be no surprise that with dire issues of academic freedom and censorship at stake, disputes within the history profession have grown testy, even bitter. Historians are fighting in public over interpretations, partly because interpretations are under public attack.

This new mode of contest within the profession emerged suddenly and accelerated fast. After the 1619 Project was published, the December open letter seeking corrections was followed up by a January 2020 article in the Atlantic by Sean Wilentz, the Sidney and Ruth Lapidus professor of the American Revolutionary era at Princeton University, who had signed the letter; his essay criticized the project in detail. Strange-bedfellowship emerged quickly too. The biggest names among the letter writers are liberal, not left, and certainly not Marxist—as he made clear in the debate, Wood criticizes what he calls ”activist” interpretations of the founding—yet the hope of swaying public opinion induced some of them to give lengthy, highly involved interviews in November of 2019 to the World Socialist Web Site, the Trotskyist online presence where, in keeping with certain old-left traditions, nothing is published that’s not lengthy and highly involved. That seemed a bit weird.

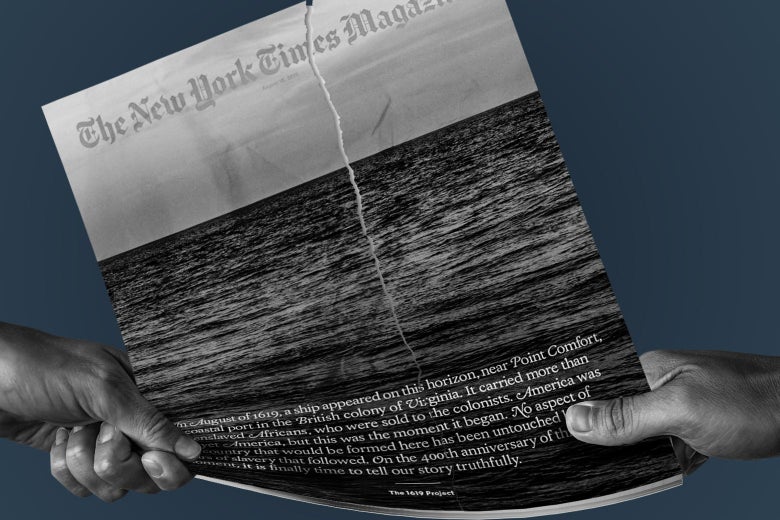

But it’s all a bit weird, because the 1619 Project has abruptly changed the ground. As an interpretation not only of the founding moment but of the whole of U.S. history, recentering the American experience on the Black experience in America, the project involved major scholarship. Yet it didn’t emerge from the usual processes for developing historical interpretations. It wasn’t slow, careful, academically curated, peer-reviewed, and opaque to public scrutiny. One random summer Sunday, the New York Times Magazine, of all things, unveiled for its big, middlebrow reading public what seemed a wholesale reframing of the nation’s entire history. If not all of the project’s content was as new as it might have looked to the uninitiated—aspects of the argument were well known, even possibly banal, in academic circles—initiation may have been part of the point. For it was this way of talking about big-picture history that had never been seen before.

Here was no history-nerd sidebar, no Father’s Day review of yet another soothing founder bio. A media company with a uniquely powerful legacy was launching a cross-company branding play by committing itself to a controversial position on a subject that the target audience was predisposed to recognize as the most important subject: the history of race in America. By awards season, the Times was running an ad for the project during the Oscars starring the singer, songwriter, and actress Janelle Monáe, wearing an 18th-century-style white dress on the beach in Virginia where the ships brought the enslaved Africans. “America was not yet America,” she said. “Yet this was the moment it began.” The ad’s tagline, “The truth can change how we see the world,” faded to that of the overarching Times campaign promoting the newspaper for the anti-Trumpian moment: “The truth is worth it.” The paper thus associated its project, in the most glamorous way, with Hollywood liberalism and resistance to Trump.

This “truth” tag, an effective bit of marketing, contradicted Hannah-Jones’ insistence that the project tells one origin story, not the only true one (the forthcoming book, too, is subtitled “A New Origin Story”—not claiming to be the one and only tale). But the combined corporate and intellectual ambition has been plain. A sense that the project reveals the truth, about race, about us, directly and accessibly to the public for the first time, lent it enormous charisma, backed by the Times’ hegemonic force in liberal culture. Lesson plans, books, and curricula were announced. The idea seemed to be to stage a takeover—from a media base, not an academic one—of the national consensus on what makes America, axiomatically, exceptional.

Such a big, fast, unpredictable move clearly upset some historians of the U.S., but not all—far from it. Well-regarded scholars were among the authors of the project’s essays, for one thing. Excitement naturally prevailed. Coming on the heels of Hamilton: An American Musical, the 1619 Project continued to popularize, if in a more serious and academic way than that Lin-Manuel Miranda show, areas of study once widely perceived as dry. And many had been objecting for a long time to what seemed the complacency, at best, of Wilentz, Wood, and others regarding the history of slavery and racism in America. Historians’ public support for the project, especially when Twitter-enabled, could be fervent. Reactions to the five letter writers’ objections ranged from eye rolls to body slams.

And so, last weekend, when the Holton-Wood debate reached its most intense sequence, the drama brought two and a half years of internecine conflict to a climax. Wood was doubling down. He didn’t blame Hannah-Jones, he said: She’s a journalist, taking her cues from the past 30 years of historical scholarship, which Wood characterized as a blanket condemnation of the American founding for failing its ideals.* Wood has been waging that particular war, within the profession and at times in the press, for decades. He persistently rules out on its face, as presentist and politically biased, any interpretation that dissents from celebrating the U.S. founding as a world-changing, liberalizing transformation, or that subjects the Founders’ values to close criticism. As he made clear in the debate, he’s not going to budge on that now. Wood is digging in.

At the other extreme, some historians who support the 1619 Project, including Holton, have begun calling the five historians who criticized it in 2019 and 2020 personally responsible for the political attacks on Hannah-Jones; for the rejection of the 1619 curriculum by school districts; and for some states’ moving to ban from the classroom, by legislation, honest discussion of race and racism in American history. From this angle, criticism of the project has become, in itself and on its face, illegitimate regardless of intention, because of the effect: right-wing seizure of the historians’ criticisms in enacting bans on the free exchange of ideas. Liberal criticism of the 1619 Project, from this point of view, has enabled the rise of Trumpian authoritarianism.

In the debate, Holton made that idea abundantly clear when calling out Wood, again and again, for placing Hannah-Jones, as Holton put it, “beyond the pale,” and thus giving aid and comfort to censorship in America. Hence all the talking-over, all the sputtering. Holton was forcing on a bemused Wood dozens of printouts of primary sources, supposedly proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that preserving slavery was a major cause of declaring American independence. In virtually the same breath, he seemed to be trying to get Wood to accept personal responsibility for having deployed a category of criticism that has placed both the 1619 Project and Hannah-Jones herself in danger. And he demanded that Wood prove his commitment to the principle of free speech by doing what Holton and everybody else know Wood, of all people, is never going to do: write a new open letter, condemning the right wing for misappropriating his opinions. Not intellectually, but in a sense rhythmically, melodically, dramatically, Holton’s push to obtain from Wood the unobtainable concession that preserving slavery motivated the Revolution became inextricably enmeshed with his push to obtain from Wood something equally unobtainable: public disavowal of the terms in which Hannah-Jones’ essay was criticized by the five historians’ December 2019 letter to the Times.

So it wasn’t a debate. More a strange kind of improv—funny, painful, oddball—showcasing the unexpected position in which professional U.S. history now finds itself, in the wake of the 1619 Project. Such a spectacle might seem anything but edifying. Maybe it’s not a good look for the discipline. Yet if this new mode of public fighting among historians knocks some of the academic mystification off the profession, reveals its practitioners as driven by emotion as well as by logic, exposes argument as inherently partial, and suggests that the truth has elusive properties, that might not be all bad, after all.

Correction, Oct. 30, 2021: This piece originally paraphrased Gordon Wood describing the 1619 Project as having been drawn from the past 50 years of scholarship, when it was the past 30.