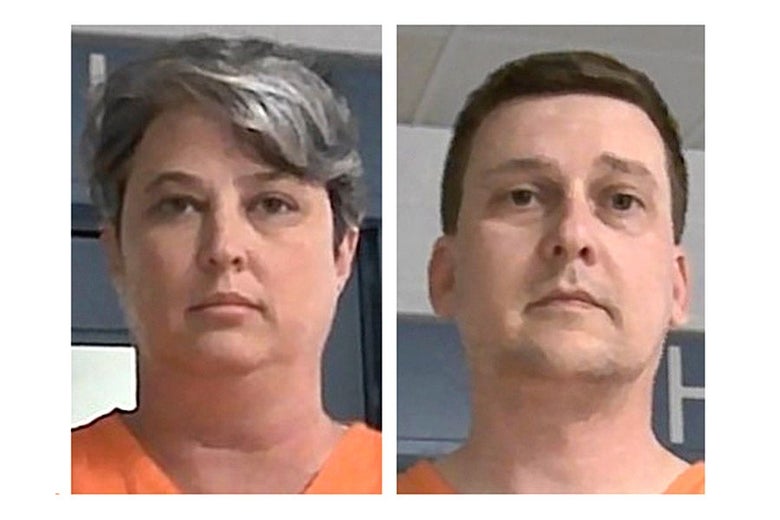

A pathetic spy trial is going on in West Virginia. Unlike our most cherished spy films and novels, as well as the most ballyhooed real-life cases of espionage, the grim tale of Jonathan and Diana Toebbe does not bank on high drama and ideological ideals. Jonathan, a 42-year-old Navy nuclear engineer, and Diana, a 45-year-old private school teacher, residents of a modest home in Annapolis, Maryland, plotted to sell secrets to a foreign intelligence agency but screwed up in the very first step of what they’d thought was a finely honed scheme.

Their motives are not yet clear; their first hearing before a judge takes place this week. But judging from the Justice Department’s 23-page criminal complaint, filed earlier this month in a U.S. district court, the couple seemed to be driven by a desire for money (not a fortune, simply a comfortable nest egg) and a bit of adventure, the prospects for which they seem to have gleaned from romanticized books and movies.

Subscribe to the Slatest Newsletter

A daily email update of the stories you need to read right now.

In April 2020, Jonathan Toebbe sent a letter to a foreign government—which the complaint refers to as “Country1,” but it seems to be France (for reasons I’ll explain later)—containing some fairly routine manuals on the nuclear propulsion system of the U.S. Navy’s Virginia-class submarine and promising much more if the recipient sent him a down payment.

That’s already where he went wrong. In December (it’s unclear why this took so long), the foreign government turned over the package to the FBI, which then assigned a special agent to the case. That agent, Justin Van Tromp, the author of the affidavit, spent the better half of the following year corresponding with Toebbe, pretending to be the foreign intelligence contact of the wannabe spy’s dreams.

What follows in Van Tromp’s affidavit is a chronicle of encrypted letters, dead drop locations, and cryptocurrency transfers, all rather expertly instigated by Toebbe, a self-proclaimed “amateur” in this realm, which suggests that he picked up the lingo and tools of tradecraft from the world of cinema and publishing. (Some of Toebbe’s letters, reprinted at embarrassing length in the complaint, seem to lift entire quotes from The Courier, the underrated movie about the Oleg Penkovsky case, which, by coincidence, I recently watched.)

Over the brief time when they lived out their fantasies, the Toebbes dropped off more than 11,000 pages of “Restricted Data” in thumb drives—in one case, tucked inside a peanut butter sandwich—in exchange for a total of $100,000 in crypto payments, with visions of much more money to come.

Then, on the morning of Oct. 9, they hired a babysitter to watch their two small children and drove to a prearranged drop spot in rural West Virginia, where FBI agents—who’d followed them there from the start of their trip—closed in for the arrest. If found guilty, the couple could be sentenced to life in prison.

What can we infer from the story, as we know it thus far?

First, it is likely that the Toebbes were trying to sell the documents to a U.S. ally. There are a few bits of evidence for this. The country’s officials turned over the initial documents to the FBI—something that Russia or China would not likely do. Early on in this caper, Toebbe asked the FBI agent, whom he thought was a foreign official, to display a signal from some property that his country owned in D.C.—likely an embassy—while the Toebbe family was visiting there over a Memorial Day weekend. Apparently the signal was sent, which means the FBI persuaded the foreign embassy to play along. Again, the Russians or Chinese would probably not have cooperated. Finally, there is this bit from a letter Toebbe sent to his contact:

Thank you for your partnership as well, my friend. One day, when it is safe, perhaps two old friends will have a chance to stumble into each other at a café, share a bottle of wine, and laugh over stories of their shared exploits. A fine thought, but I agree that our mutual need for security may make that impossible. Whether we meet or no, I will always remember your bravery in serving your country and your commitment to helping me.

Leaving aside for a moment the pitiful naïveté that this letter conveys in retrospect, where might the daydreaming Toebbe envision such a future run-in to take place? The wine, the café—it could be anywhere, but sounds a lot like a wannabe spy’s vision of post-heist life in Paris.

So let’s say it’s France. If French officials cooperated with the FBI on this matter, it must have been particularly galling when the Biden administration then struck a deal to share nuclear technology with Australia, thus squelching a contract that France had negotiated long ago. This is the same nuclear technology that the Toebbes thought they were providing to France. If France had taken the Toebbes up on their offer, it might have been able to save the contract with Australia. Instead, the French notified the FBI—and for their trouble, they got screwed. This may be the backstory on why French President Emmanuel Macron was particularly peeved.

This leads to a larger question: Just how traitorous were the Toebbes? How damaging would it have been to U.S. security if France—or whatever nation was involved, assuming the nation was an ally—had acquired this technology?

It’s not entirely clear from the complaint, which redacts several passages of Toebbe’s letter describing the contents of the documents and how they might help “Country1’s” navy. However, their indiscretions seem pretty severe—and unambiguously criminal.

Jonathan Toebbe was a Navy engineer, working on the Virginia-class submarine’s nuclear propulsion system since 2012. He also worked on the technology that makes those submarines particularly quiet—and thus undetectable to any adversary as they prowl underneath the ocean’s surface.

If Country1 is France, would it have mattered if the French acquired these secrets? Maybe not. But maybe so, especially if some French spy passed the secrets on to some other country. In one of the most infamous spy cases of recent years, Jonathan Pollard, a Pentagon official, supplied U.S. nuclear weapons secrets—true “crown jewels” of intelligence—to Israel, which, according to some reports, passed them on to the Soviet Union, in exchange for a more liberal policy allowing the emigration of Russian Jews.

On the scale of perfidy, the Toebbes don’t remotely approach Pollard. They are charged with violating the Atomic Energy Act, which, in the words of the complaint, prohibits, among other things,

individuals who have possession of, access to, control over, or are entrusted with any document, writing, sketch, photograph, plan, model, instrument, appliance, note, or information involving or incorporating Restricted Data from communicating, transmitting, or disclosing it to any individual or person, or attempting or conspiring to do so, with the intent to injure the United States or to secure advantage to any foreign nation.

This statute covers a broad swath of offenses. It bars not only disclosing this material but merely “attempting or conspiring to do so.” (In other words, legally, it doesn’t matter that the Toebbes didn’t actually provide much to Country1.) And the leak is criminal if its consequences “injure the United States” or if they “secure advantage to any foreign nation.” And note the phrase “any foreign nation”—it doesn’t matter if the country is friend or foe. Note also that it’s immaterial whether the leak actually injures the United States or helps a foreign nation; it is criminal merely if the leaker acted “with the intent” to do so.

And the Toebbes seemed to have that intent, or at least Jonathan Toebbe did. In one letter to his contact, he wrote, “I have considered the possible need to leave on short notice,” presumably if the feds found out what he was doing. “Should that ever become necessary, I will be forever grateful for your help extracting me and my family.” (This too, by the way, is a near-verbatim quote from The Courier.)

Jonathan and Diana Toebbe reportedly have obtained separate lawyers for this trial—which raises the possibility of a schism in the defense. Diana’s lawyer may argue that she had no knowledge of what was going on—hence, no intent. The Justice Department’s complaint portrays her mainly as a lookout—making sure that no one was watching while her husband planted the thumb drives in various drop boxes. The complaint quotes no letters from her, nor does it cite evidence that she had possessed or saw Restricted Data. (Jonathan had a Q security clearance, providing access to atomic secrets; Diana did not.)

This legal tactic—a sensible move by any defense attorney—would abase the proceedings with another cliché of human banalities: the family squabble.

Jonathan Toebbe, and perhaps Diana too, aspired to join the ranks of dashing secret agents from literature and history. But their story, at least what we know of it so far, is pulp of the grimmest, saddest sort—no heroes or antiheroes, no grand visions, just an all-too-ordinary, stupid plot set in motion by smart people who weren’t nearly as smart as they thought they were.