A neighbor saw the boys first.

Four-year-old Kenneth was crying as he led his younger brother, William, down 97th Avenue in Oakland. William, too, was weeping. They couldn't have looked more lost if they'd tried. When the woman asked them what was wrong, Kenneth sniffled. "Grandma told us not to leave home," he said. "She was going to the store to buy doughnuts and chocolate milk."

The woman said she would help them. After all, their grandmother couldn't have gone far if she was just making a trip to the corner store. But they wandered the streets for an hour without any sign of her. The boys were exhausted, so the good Samaritan flagged down a passing patrol car. An officer gently loaded the boys into his vehicle and drove them down to the station.

There, Kenneth chatted willingly. He said his parents had died in a car crash, and their grandmother had brought the boys by bus to Oakland. When Kenneth said they lived in Florida, one officer felt the hairs on the back of neck stand up. He grabbed the day's newspaper, its front page plastered with images of America's most wanted murderer.

"Do you know who this lady is?" the officer asked Kenneth.

"Oh," the boy exclaimed. "That's grandma!"

---

For nearly 200 years, San Francisco has been the last stop of petty thieves, con artists and killers. Iva Kroeger was all three.

Iva was born Lucille Hooper in Kentucky in 1922, the daughter of day laborer William Hooper and Norwegian immigrant Zellma Hergis. The details of her childhood are sparse, but she burst onto the police blotter in 1945 with the first salvo in her lifelong crime spree. She was arrested in Chicago after police were tipped that a young woman was going around pretending to be a war hero. Lucille Hooper was apparently bragging that she was a Navy nurse who had survived a stint in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. The War Department had no record of any such person, and she was charged with illegally wearing the uniform of a military nurse. She pleaded guilty and immediately violated the terms of her probation by heading west.

In her dust, she left behind a husband in Louisville, their two sons and her old identity. As she racked up misdemeanor theft charges, she also accrued a rolodex of fake names. Depending on who she met, she was Paula Marie Pearson, Lucille Cecelia Huffman, Paula Mydel Byrd, Paula Shoemaker or Lucille Cooper, just to name a few. For reasons unknown, she had settled on Iva when she met and married Ralph Kroeger, a San Francisco man who made a living carrying bricks (seriously), in 1954.

There was no marital bliss in the Kroeger home at 490 Ellington Avenue in San Francisco’s Outer Mission. They were perpetually broke, and they complained often about creditors nipping at their heels. Fleeing bill collectors, the Kroegers, using the names Eva and Ralph Long, moved into a cheap Santa Rosa motel in November 1961.

The seeds of Iva’s plan quickly sprouted. Across the street was another low-rent motel, the Rose City Motor Court. Iva began inquiring if the motel was for sale. It wasn’t, so she next ingratiated herself with the owners, Mildred and Jay Arneson. Mildred, 58, was a nurse, and Jay, a World War I major, was suffering from the advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease.

Although photos show a dead-eyed, dour woman, Iva’s career as a con artist suggests she must have been charming and persuasive. Within a month, she’d convinced her new Santa Rosa friends that she was awarded $100,000 in an accident claim. Iva said she wanted to spend the money on an all-expenses-paid girls’ trip to Brazil, and Mildred happily agreed. Mildred took out over $1,000 in traveler’s checks and wrote to her mother in Washington to let her know she was headed out of the country for a bit.

But weeks turned to a month, and Mildred’s family began to worry when they heard nothing from their loved one. They asked Santa Rosa police to send someone to the Rose City Motor Court. The dispatched officer was met by the new proprietor, Iva, who told him Mildred signed the deed over to her shortly before leaving on a trip. She figured Mildred was just on an extended vacation in Mexico. The officer gave her the phone number of Mildred’s sister, Beatrice Brunn — which he mistakenly wrote as “Brown” — and told Iva to give the family a call when she could.

A few weeks later, two mysterious notes arrived at the doors of Mildred’s family. Her mother got a letter signed “Mildred'; family members knew she always signed correspondence as “Mil.” Her sister Beatrice, meanwhile, received a telegram addressed to Beatrice Brown, the same mistake made by police. The family became even more convinced something sinister had happened.

The 1300 block of Santa Rosa Avenue in Santa Rosa, which was once the home of the Rose City Motor Court.

Google Street View"We know our sister," one sister told the press. "She wouldn't leave without letting us or her daughter know."

By this time, Jay Arneson too had disappeared. In late January, Iva, Jay and two friends drove to San Francisco. They stopped at the Ellington Avenue home, where Iva requested they help with some “plumbing” work in the garage. One of the friends dug a large hole in the floor while the rest watched, and then all drove to a nearby hospital for Jay’s doctor’s appointment. Iva escorted Mildred’s husband inside the hospital, and then returned a short time later to tell her waiting friends to head home without them; it was going to take a bit longer for the doctor to see him. The friends drove back to Santa Rosa, never to see Jay again.

To the frustration and horror of the Arnesons’ family members, police shrugged their shoulders, assuming the missing couple had indeed gone abroad. All of Iva’s paperwork was in order, and it seemed she did indeed lawfully own the motel.

Months passed. Iva put the motel on the market for $72,000. Ralph moved back to San Francisco. Finally, on August 20, eight months after Mildred disappeared, police executed a search warrant on the Ellington Avenue home. They noticed right away that there were two uneven, gray patches in the light blue garage floor. Police started digging.

They found Jay’s body first, the belt used to strangle him still around his neck. Under the other patch was Mildred, stuffed into a trunk. She, too, had been choked to death.

At last, the noose was closing in on Iva. But she was already gone.

---

A few months prior, Iva pulled a gun on a water company worker who came to the motel demanding she pony up $4,900 in unpaid bills. Furious, she waved around a pistol and threatened to kill him. Santa Rosa police issued an arrest warrant, and Iva went on the run.

Now accused of three violent crimes, Iva became America’s most famous murderess overnight. Her photo ran on front pages across the nation, accompanied by the description: "She has a bad temper, and is a proverbial liar." Papers dubbed the 44-year-old the "ghostly grandma," "glib grandmother" and, least flattering of all, "dumpy grandma."

Tips poured in, most of them worthless, but police did nothing to tamp down hysteria throughout the Bay Area. One detective casually speculated that Iva was likely laying low as a babysitter “for some unsuspecting San Francisco family.” A slightly more helpful detective warned Iva’s friends that anyone who aided the fugitive “might wind up under their own patio.”

"If anyone crosses her path and doesn't have enough sense to get in out of the rain, then they're sure going to get wet," San Francisco chief of inspectors Dan McKlem said.

Two days after the manhunt began, Iva’s grandsons were found wandering the streets of Oakland. The boys’ parents told a shocking story. After years without contact, Grandma Iva had recently appeared at their door. She said she’d just bought a motel in California, and she wanted help running it. She promised to take the boys first, and would soon send the money for her son Kenneth and his wife Joyce to join them.

"She was the type that could talk to anyone and make them think the moon's gold,” Joyce told the Oakland Tribune.

"We were having it real tough,” Kenneth added. “She made it sound so good we fell for it hook, line and sinker.”

Police guessed Iva had kidnapped the boys and set them loose in Oakland to throw authorities off her trail. Joyce had another theory. Several years after abandoning her children and husband in Louisville, Iva suddenly wanted custody of her sons. She asked Kenneth to come live with her instead of his father. He told her no.

"Mrs. Kroeger told someone that Kenny had hurt her deeply,” Joyce remembered, “and that someday she would hurt him the same way."

---

Meanwhile in San Francisco, crowds swarmed the Kroeger home. Police guarded it day and night after an over-eager souvenir seeker broke a window.

As was customary at the time, reporters were allowed to traipse all over the scene, taking photographs and touching whatever they liked. An Examiner reporter found a new, taffeta-bound baby book filled with cards. "Congratulations on your twins!" read one from the Longfellow Elementary School PTA. A list in the back of the book detailed dozens of gifts from friends. Iva hadn't had a baby — let alone two — in over a decade.

Ralph Kroeger, who Iva hadn’t bothered to warn of the impending chaos, had been living in the home, basement bodies and all. After he was taken in custody and charged with murder, he spent most of his time denying his involvement. (Although it’s unclear if he was directly involved in the killings, there’s no doubt he knew what was buried in his garage; witnesses placed him there at the time of some of Iva’s “plumbing” renovations). Ralph also complained loudly about the motel to anyone who would listen.

"That damn place! I worked up there cleaning that joint up. It was a condemned joint,” he whined to the Examiner from prison. “They were getting ready to close it up until I started painting it. It wasn't fit for hogs to live in. That's the reason I wouldn't live in a place like that under my own name."

On September 9, Iva was spotted at a San Diego church. Her choice to flee to San Diego sent alarm through the Arneson family; Jay's sons Jack and Dick lived five miles away. Police warned them to be vigilant. Both men began carrying guns with them at all times.

Later that day, a World War II POW named Joseph Bonamo saw a tired-looking woman on his street. He didn't recognize her and struck up a conversation. She said she was destitute and struggling to make ends meet with a sick nine-year-old daughter. Joseph, who hated to see anyone go hungry, invited her to dinner with his wife Christine.

Once inside the Bonamo home, the woman began acting strangely. She refused to take off a pair of dark sunglasses and twice requested to make calls, dragging the phone into a bedroom and shutting the door behind her. When the Bonamos began chatting about all the violence in the news, the woman lifted her head and commented, "The Bible says it is wrong to kill."

The next day, Joseph and Christine were paging through the newspaper when they stopped on a photo of a wanted woman named Iva Kroeger. Christine grabbed a pen, and drew two dark sunglass lenses over the woman's eyes. She looked exactly like their dinner guest.

Joseph called the local police, who told him they were done working for the day, and recommended he call back later. Luckily Joseph realized the urgency of his tip, even if the police didn't. He tried the FBI, which immediately sent officers to the woman’s east San Diego apartment. For the first time in her life, Iva gave up without a fight.

"I'm overjoyed and tremendously relieved," Jack Arneson told reporters. "Now I can take the shells out of the .38."

---

Relief would soon turn to disgust, though, as Iva kicked off a media circus that Court TV could only dream of.

Hoping to crack their cardigan-wearing murder suspect, police dragged Iva back to San Francisco for a shocking surprise. In her garage, they gathered four of the prosecution’s witnesses to confront her at the Arnesons’ makeshift graves. "The treatment, designed to break down the most hardened criminal, did not faze the elusive grandmother one whit,” the Santa Rosa Press Democrat reported. It did faze her attorney, however, who understandably hit the roof, shouting that his client’s constitutional rights had been violated.

Police brought Iva Kroeger to her San Francisco home where she buried two bodies, confronting her with witnesses to the crime. This front page ran on the Press Democrat on Sept. 13, 1962.

Santa Rosa Press Democrat archivesOn the way out, a crowd of 300 onlookers jostled for a closer look at the killer. Photographers’ flash bulbs snapped and lit up the normally quiet street. The Press Democrat described the scene as “reminiscent to the appearance of a Hollywood great attending a sure box office hit on opening night." Iva smiled, stopping briefly to proclaim her innocence to the gathered media.

“I sleep good, and I’m just a happy person,” she said.

The trial of Iva and Ralph Kroeger began in January 1963. In the intervening months, Iva had settled on a strategy: She was going to fake her way to a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. She kicked off the trial by escaping her guard and bum-rushing the assistant D.A., throwing a rosary over his shoulder. Iva spent the rest of jury selection glaring so hard at one woman that the judge ended up dismissing her. Iva also gleefully told reporters she’d been reading astrology books to pass the time. "I want to make up some charts,” she said. “I'm going to find out the birthdays of all the people in that trial and if any of them is lying, maybe I'll come up with some surprises." A few days later, one of the jurors’ husbands died of a heart attack. The media blamed Iva’s “hex.”

Throughout witness testimony, Iva talked relentlessly and took off her shoes to bang on the defense table. "Irascible Iva Kroeger didn't take the witness stand yesterday but she might as well have,” the Examiner reported. Ralph pinched her arm “black and blue” as he “repeatedly jabbed her and asked her to keep quiet.”

Then, for utterly incomprehensible reasons, Iva’s lawyer decided it would be a good idea to put her on the stand. She screamed for 15 minutes straight while the judge begged her to calm down. “You should force her to testify,” he told her lawyers. “This is the time.”

“I can’t be forced to do nothin’,” she shouted back. “You can’t make a horse take a drink.”

After calling a recess for Iva’s lawyers to talk her down, she returned willing to testify. It went extraordinarily poorly. She started off monologuing for an hour straight, listing off grievances and rambling about police wrongdoings. When the prosecution was allowed to cross-examine her, the farcical proceeding hit a new low.

"Iva Kroeger tried to match wits with the prosecution yesterday but it was the St. Valentine's Day Massacre all over again,” the Examiner wrote. “By actual count she tripped herself up 42 times."

Seeing that things were not going her way, Iva broke free of her seat and “leaped around the court like a deer,” eliciting gasps from the gallery. When this was not enough to end the cross examination, Iva raced over to the district attorney’s table and swept his papers off it with hysterical yelps. The bailiff had to pick her up and forcibly remove her from the courtroom.

Three psychiatrists then testified that Iva was perfectly sane and only faking her madness to get out of legal consequences. "She's naughty,” said one on the stand. "She lies with ingenuity, cruelty, wickedness, cool calculation and evil conduct and intent — like a devil."

After nearly two months of courtroom antics, the jury was sent to deliberate. It took them only five hours to return guilty verdicts for both Iva and Ralph. Neither made much of a fuss, with Iva feebly declaring the jury was “paid off” and Ralph, ever the sad sack of a man, murmuring, “I didn’t expect it.”

---

This was not the end for Iva Kroeger, although it was for Ralph. In 1966, two years shy of Johnny Cash’s infamous visit, Ralph died of cancer at Folsom Prison. His obituary noted that he would have likely been found not guilty if he’d elected to be tried separately from Iva. There was, after all, no physical evidence directly linking Ralph to the murders. But he’d been loyal to the end, and he died alone in prison.

Iva, it was reported, was going blind and learning braille to cope. In 1975, she was granted parole; the board praised her behavior while incarcerated and cited her failing vision as a factor in her being unlikely to reoffend. The Press Democrat said she moved to Riverside, where she was taking classes at the University of California and attending a local church of Scientology. Her parole officer told the paper she was back to using her birth name, Lucille, and was known as “a bit of a nuisance” among city bus drivers. She apparently liked to ride around, white cane in hand, and complain to strangers about serving “13 years for a crime she didn’t commit.”

It seemed her years of infamy were over when, out of the blue, she made headlines again in 1987: Police in Cape Coral, Florida were seeking her arrest for allegedly threatening to murder a man she blamed for the tragic drowning of one of her grand-nieces. The man told police the 69-year-old had repeatedly made violent calls to his home before showing up to kill him. When police ran her name, they found her criminal record. They were astonished, in no small part because the woman they were investigating showed no sign of visual impairment. They wondered if she’d faked it in order to secure an early release and, having achieved her goal, could then apply for state aid for blind residents.

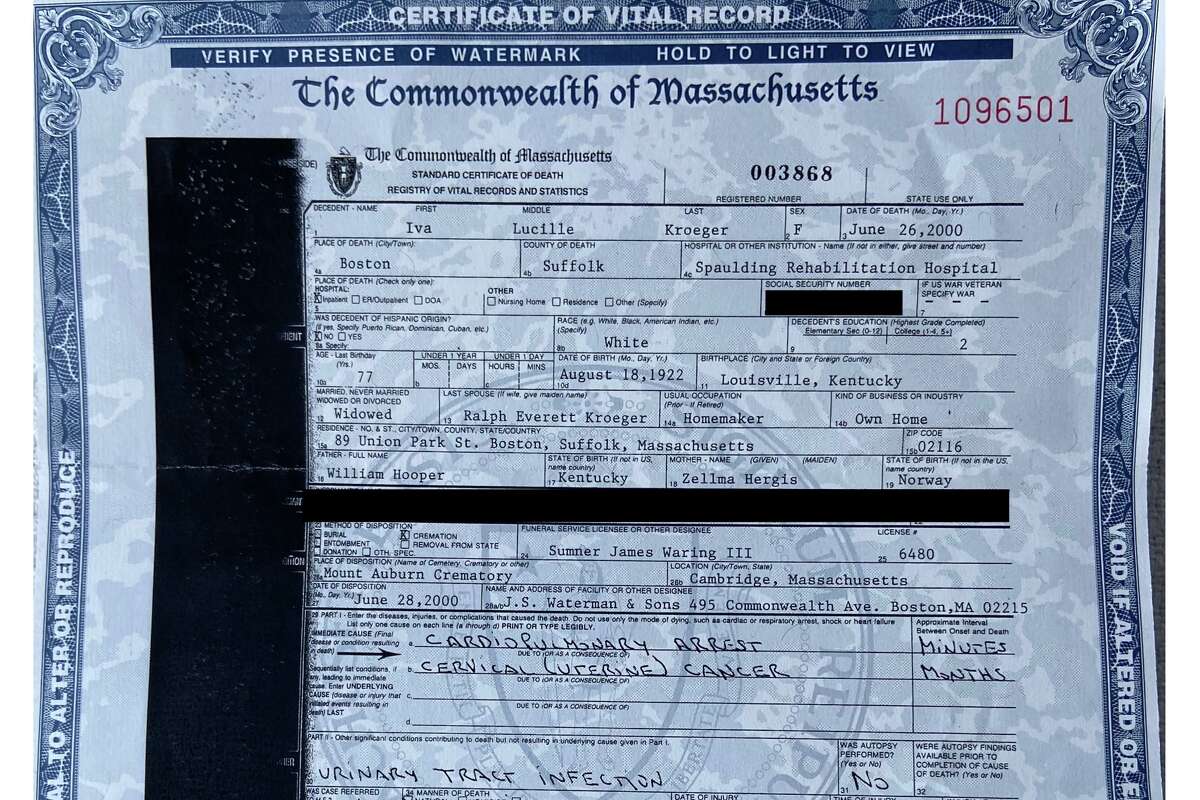

What happened next is a mystery. There are no further stories about an arrest, and Iva disappeared permanently from the public eye. No obituaries ran when she died in 2000, but a gravestone with her name surfaced upon searching public cemetery records. The grave was in Boston, so we sent a request to the city for her death certificate.

It arrived in a few days, the last known bits of Iva Kroeger’s life. She is listed as Ralph Kroeger’s widow, her occupation “homemaker.” At the time of her death, she was living in what appears to be public housing on Union Park Street in Boston. Her next of kin was not kin at all, but a social worker. She died of cervical cancer.

The death certificate for Iva Kroeger, issued by the city of Boston. She died of cancer in 2000.

Katie Dowd/SFGATEAs for the Kroeger house on Ellington Avenue, it was seized by the bank in 1962. A year later, it was back on the market. A real estate listing in the Chronicle asked $22,500 for the property. “Four bedrooms, 2 baths! ½ block Mission St.! Vacant!” the listing read.

It’s not clear what happened to Iva’s many furnishings inside the home. More likely than not, they were sold off by the bank to make a few bucks. Somewhere in the Bay Area, someone may unknowingly have Iva’s table or chairs. And it’s possible someone ended up with the plaque that once graced the entryway, a poem dedicated to the joys of friendship.

"My friend is one who knows me well,” it read. “Yet loves me just the same."