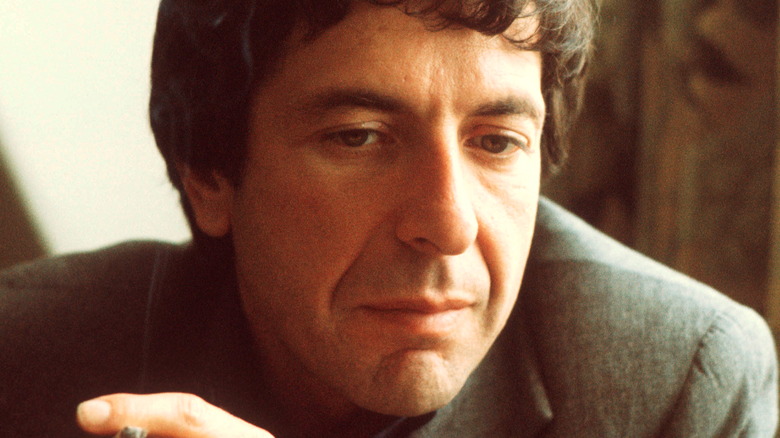

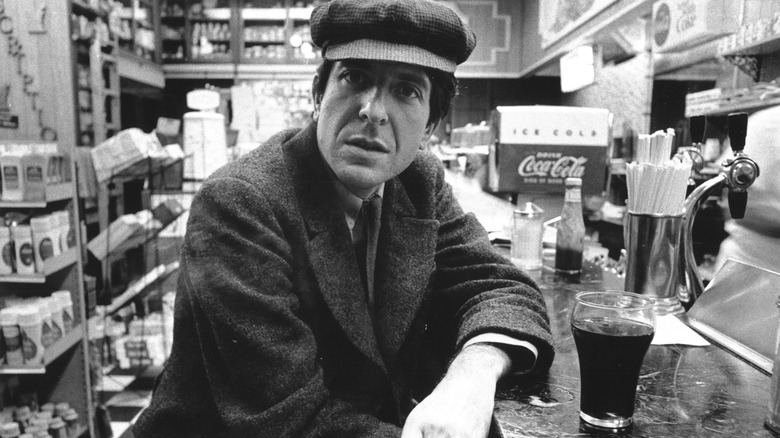

Michael Putland/Getty Images

"There is a crack in everything," the Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen famously sang in his 1992 song "Anthem" (via Genius). "That's how the light gets in." In some ways, this particular lyric encapsulates Cohen's life and work. He was famously moody — in fact, his moodiness boosted his fame. Which is to say, the acute poignancy of Cohen's writing is a major part of the reason why his songs were and continue to be so impactful.

"Depression has often been the general background of my daily life," Cohen once told Rolling Stone. "My feeling is that whatever I did was in spite of that, not because of it. It wasn't the depression that was the engine of my work ... That was just the sea I swam in."

Cohen spent much of his life pushing through his inner darkness, whether through religion and spirituality, through romance or sex, through travel or reclusivity, or through poetry or lyricism. The singer-songwriter was ultimately a testament to the fact that age or internal struggles or popular commercial interests cannot keep a person from living out their dreams and letting the light in. Here's more on the singular life of one of the greatest songwriters of all time.

Leonard Cohen's relationship to Judaism evolved

Colin Woods/Shutterstock

Leonard Cohen was born to Jewish parents in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. "I had a very Messianic childhood," he told Richard Goldstein in 1967 (via Crawdaddy magazine), "I was told I was a descendant of Aaron, the high priest." Cohen's grandfather, Rabbi Klinitsky-Klein, wrote a thesaurus of the Talmud, according to the Jewish Chronicle. His other grandfather founded many important Jewish institutions in Montreal, including the Montreal Anglo-Jewish Times and the city's Sha'ar Hashamayim synagogue. Cohen was even a youth leader in summer camps run by the Jewish organization B'nai B'rith. As an adult, he paid multiple visits to Israel, including during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when he tried to join the fight but was persuaded to do so through music.

As Cohen grew older, he began to explore religion on a wider scale. "Anything, Roman Catholicism, Buddhism, LSD, I'm for anything that works," he once said (via The New Yorker). He briefly studied Scientology, and later in life spent countless hours at the Ohr HaTorah synagogue on Venice Boulevard, where the rabbi, Mordecai Finley, occasionally read aloud from Cohen's 1984 collection "Book of Mercy."

Cohen later spent years living in a Buddhist monastery — more on that later. "I even danced and sang with the Hare Krishnas," he once said (via The New Yorker). "No robe, I didn't join them, but I was trying everything."

Leonard Cohen began with a focus on poetry

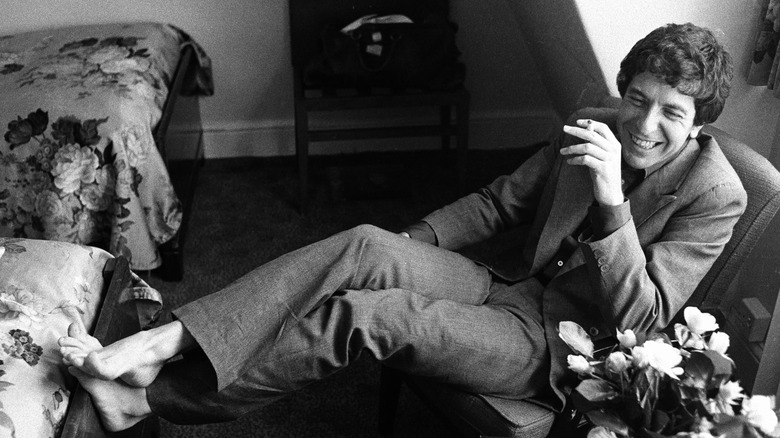

Michael Putland/Getty Images

In 1951, Leonard Cohen enrolled at McGill University in Montreal. He was mentored by his professors, the Canadian poets Irving Layton and Louis Dudek, as noted by Vice. In 1956, a year after Cohen graduated, Dudek oversaw the publication of his former student's first poetry collection, "Let Us Compare Mythologies," per McGill News. Cohen also earned a McGill literary prize for his poem, "Sparrows," which features the line, "But what shall I tell you of migrations/when in this empty sky/the precise ghosts of departed summer birds/still trace old signs" (via Vice).

"There was ... a very fine group of poets in [Montreal], where I got my training," Cohen told Crawdaddy magazine in 1975. "We'd put out our own books, our own magazines, there was no contract or deals made with any other part of the world, we did consider ourselves self-sufficient, and the training was quite rigorous."

By the time Cohen's second book, "The Spice-Box of Earth," was published in 1961, he was nominated for the prestigious Canadian E.J. Pratt Medal for Poetry and even called "probably the best young poet in English Canada right now" by one critic (via Vice). His first novel, "Beautiful Losers," was published five years later. It was a commercial flop but a critical darling. Cohen's talent and passion for poetry and literature naturally laid the groundwork for him to become one of the greatest songwriters of all time.

Leonard Cohen had a strong connection to the Greek island of Hydra

O.I. Tusitala/Shutterstock

In April 1960, a 25-year-old Leonard Cohen was holed up in London, trying to write three pages a day on a Canadian Arts Council grant, as noted by The Guardian. One night he met someone at a party whose fiance owned a mansion on the Greek island of Hydra, where creative figures including the writer Henry Miller sometimes stayed. Cohen was sold, and he headed from his rainy London boarding house to the 40-room mansion on the sunny island. When he got there, he was met with a rude awakening: A housekeeper turned him away for being Jewish. Cohen later claimed he put a curse on the house, and it burned down the following year.

Still, Cohen ended up buying his own house on the island and staying there for several years. It was on Hydra that he isolated himself from much of the world and worked tirelessly on his writing work, including his debut novel, "Beautiful Losers." According to Suitcase magazine, Cohen looked out his window one day to find a telephone wire being installed outside, much to his disappointment. "Civilization had caught up with me," he later said of that moment (via Suitcase). "I wasn't going to be able to escape after all. I wasn't going to be able to live this 11th-century life that I thought I had found for myself." That development, and the island as a whole, inspired Cohen's song "Bird on a Wire."

Leonard Cohen had a passionate romance with Marianne Ihlen

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In the spring of 1960 on the Greek island of Hydra, Leonard Cohen met and befriended a single mother named Marianne Ihlen, as noted by The Guardian. They soon became lovers, and Ihlen sent her son back to Norway to live with his grandmother while Ihlen herself moved in with Cohen on Hydra. He provided for her, and she took care of him while he spent hour after hour working on his novels.

When his debut novel, "Beautiful Losers," was finished, Cohen was hit with the troubling realization that he would never fully be able to provide for himself, let alone Ihlen, as a writer. He then turned his attention toward music, which marked a beginning for his career, and the beginning of the end for his romance with Ihlen. Their relationship continued sporadically throughout the decade and across the world.

Ihlen was hopelessly in love with Cohen, but he kept her at an arm's length from the Chelsea Hotel scene. In 1972, a young woman named Suzanne Ehlrod knocked on the door of the house Ihlen shared with Cohen on Hydra, and asked when Ihlen would be moving out. Ehlrod was holding the infant son she shared with Cohen. Ihlen eventually moved on with documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield, whose documentary "Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love" was released in 2019. The love affair between Cohen and Ihlen is also immortalized through Cohen's song "So Long, Marianne."

Leonard Cohen originally planned to be a country singer

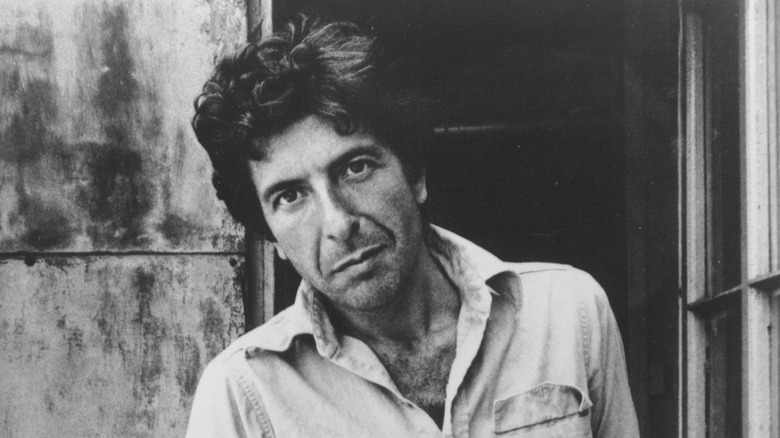

Michael Putland/Getty Images

In 1966, at the age of 32, Leonard Cohen found himself with the opportunity to host a local current affairs radio show called "Seven on Six" in Montreal, per CBC. One night shortly before he was due to sign the contract, he allegedly smoked some marijuana and had a change of heart. He called CBC TV producer Andrew Simon and reportedly told him that he couldn't do the show because he was going to be a songwriter instead.

Cohen's decision to foray into music was due in part to the exciting evolution of the music scene in the 1960s. "Living in Greece most of the time, I had been completely unaware of the whole renaissance in music that was taking place in the early and middle 1960s," Cohen told Rolling Stone. "Still, I was playing a lot of guitar and I thought, 'It's all right being a writer – I always want to be a writer – but I think I'd like to go to Nashville and make some country-western records ... I decided, 'That's going to build me up.' I had some songs sketched out."

"In Canada we listened to a lot of country and western music, and I used to be in a country and western group when I was quite young," Cohen told Crawdaddy magazine in 1975. "So I thought I would head down to Nashville ... This was mostly an economic consideration; I'd published a lot of books but I'd never sold very many."

Leonard Cohen started his music career at age 33

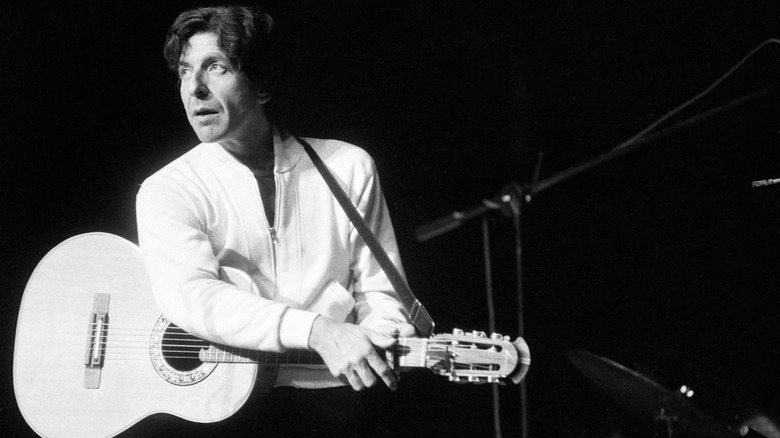

United Archives/Getty Images

On his way down south in 1966, Leonard Cohen made a fateful pitstop in New York City, where he met members of the musical renaissance including Bob Dylan and Lou Reed."Romantic figures, these troubadours," Cohen told Rolling Stone. "They were me; that's what I was, drifting around the world, speaking from the heart and occupying a certain mythological life. I felt very close to them."

Cohen was already in his early thirties by the time he entered the New York music scene, but in it, he finally felt somewhat understood. "There was a sensibility — not in any way new to me, because I was already 32 or 33 years old — but a sensibility that I thought I was quite alone in," Cohen recalled to Crawdaddy magazine. "It wasn't quite Kerouac, it wasn't quite Ginsberg, it was something after that ... I found that or a compatible sensibility flourishing [in New York]! So I was very happy, I felt very much at home."

Judy Collins helped kickstart Leonard Cohen's career

John Byrne Cooke Estate/Getty Images

In 1966, a mutual friend arranged for Leonard Cohen to play some songs for the singer Judy Collins. Cohen showed up at Collins' apartment with a guitar, and began playing "Suzanne." "I fell right off my chair," Collins recalled to CBC. "It was so different and so evocative of something that was almost ethereal — and how could that be in a song that was so grounded?'" Collins went on to record several songs Cohen had written.

In 1967, Collins asked Cohen to perform at an anti-Vietnam War benefit at The Town Hall in New York City. "I can't do it, Judy," he reportedly told her, per The New Yorker. "I would die from embarrassment." Collins managed to persuade him, but watching him on stage from the wings that night, she saw "his legs shaking inside his trousers," as she recalled in her autobiography "Trust Your Heart." Cohen stopped halfway through the first verse of "Suzanne" and left the stage. He managed to return following encouragement from Collins and the audience.

"It stems from the fact that you are not as good as you want to be — that's really what nervousness is," Cohen told The New Yorker. "That first time I went out with Judy Collins, it wasn't to be the last time I felt this."

'Hallelujah' didn't see immediate success

Oliver Morris/Getty Images

Many people regard Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" as the seminal work of his career, but the poignant ballad was no overnight success. In fact, by the time Cohen began writing it in 1984, he had been out of the spotlight for several years, following a few albums that performed poorly. According to one episode of Malcolm Gladwell's podcast, "Revisionist History," it took Cohen five years to write a version of "Hallelujah" he was satisfied with. When he first played the song for record label executives, they did not hear anything special in it and nearly refused to release it.

Luckily, the song took on a life of its own thanks to several of Cohen's fellow musicians. John Cale heard Cohen perform the song live in New York, and decided to record a cover version with a few lyrics of his own, moving it closer to the popular version many know today. Nearly a decade after Cohen's song was first released, Cale's version caught the ears of a young Jeff Buckley, who went on to perform a cover of Cale's version at a bar in the East Village. A Columbia Records executive was in the audience, and he subsequently signed the singer, who then recorded what is now one of the most beloved versions of "Hallelujah."

Countless other artists have since thrown their own "Hallelujah" covers into the mix. "I think it's a good song," Cohen said of "Hallelujah" in 2009 (via Rolling Stone). "But I think too many people sing it."

His affair with Janis Joplin

pxl.store/Shutterstock

At 222 West 23rd Street in New York City lies the infamous Hotel Chelsea, which is where countless artists, writers, rock stars, and starlets have lived, created, loved, and even died. "I came to New York and I was living at other hotels and I had heard about the Chelsea Hotel as being a place where I might meet people of my own kind," Leonard Cohen told SongTalk in 1993 (via Rolling Stone). "And I did. It was a grand, mad place."

One night in the spring of 1968, Cohen found himself in the hotel elevator with none other than Janis Joplin. "My lungs gathered my courage," he recalled in 1988 (via Rolling Stone). "I said to her, 'Are you looking for someone?' She said 'Yes, I'm looking for Kris Kristofferson.' I said, 'Little lady, you're in luck, I am Kris Kristofferson.' ... We fell into each other's arms through some process of elimination."

The artists' fling only lasted that one night, they only ran into each other a few times thereafter, and Joplin died of an overdose two years later, in 1970. In 1971, Cohen began immortalizing that night by writing a few lyrics on a cocktail napkin, which would become one of his most notable songs, "Chelsea Hotel #2." He revealed that the song was about Joplin during a 1976 concert, but grew to regret it. "There was the sole indiscretion, in my professional life, that I deeply regret," he told the BBC in 1994 (via Rolling Stone).

He spent years in a Buddhist monastery

Kit Leong/Shutterstock

In 1993, Leonard Cohen journeyed to a Zen monastery in Mount Baldy in Southern California, where he had previously studied meditation and Zen teachings for months at a time, per The New Yorker. This time, he stayed there for nearly six years straight.

At the monastery, Cohen lived in a tiny cabin. He woke up at two-thirty in the mornings to shovel snow, light fires, and clean toilets, and he meditated for several hours each day. "Nobody goes into a Zen monastery as a tourist," Cohen told The New Yorker in 2016. "There are people who do, but they leave in ten minutes because the life is very rigorous ... In a certain sense you toughen up. Whether it has a spiritual aspect is debatable. It helps you endure, and it makes whining the least appropriate response to suffering. Just on that level it's very valuable."

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg once asked Cohen how his devotion to Zen affected his relationship with Judaism. Cohen maintained that he was loyal to Judaism, and that he thought of Zen more as a discipline than a religion. He became a monk in 1996 but left the monastery a few years later. "I left my robes hanging on a peg/in the old cabin/where I had sat so long/and slept so little," he wrote in his 2006 poetry collection "Book of Longing," adding, "I finally understood/I had no gift/for Spiritual Matters."

A friend's betrayal left Leonard Cohen almost broke

Roz Kelly/Getty Images

In the fall of 2004, Leonard Cohen discovered that his finances, which he believed totaled over $5 million to fund his retirement, had been reduced to a mere $150,000, as reported by Macleans. "I was devastated," he told the Canadian magazine. "You know, God gave me a strong inner core, so I wasn't shattered. But I was deeply concerned."

Cohen was tipped off about the missing money by an "insider" with loose ties to Cohen's longtime friend, former lover, and personal manager of 17 years, Kelley Lynch. The songwriter then discovered several "improprieties" with his accounts, including the fact that he had unknowingly paid Lynch's $75,000 American Express bill. The day he discovered this fact, Lynch tried to withdraw another $40,000 from Cohen's accounts. The songwriter and his legal team then discovered an elaborate system of financial impropriety orchestrated by Lynch.

Cohen and his lawyers then wondered whether Cohen's investment adviser, Neal Greenberg, was involved in the improprieties. At the suggestion of involvement, Greenberg filed a lawsuit accusing Cohen and his lawyer of conspiracy, defamation, and extortion, and Lynch of stealing money from Cohen. The lawsuits kept Cohen from accessing any of his remaining money but ultimately led him to kick his music career back into gear. "This has propelled us into incessant work," he told Macleans in 2005. The songwriter was ultimately awarded $9 million in a Los Angeles civil suit filed against Lynch, per CTV.

Leonard Cohen predicted his own death

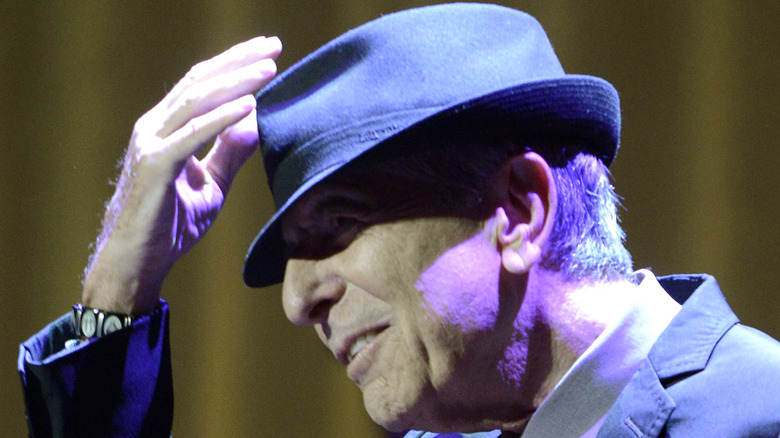

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

In July 2016, Leonard Cohen's longtime love Marianne Ihlen was diagnosed with leukemia. Cohen heard the news and wrote her a final letter, via email: "Dearest Marianne," it read (via The Conversation), "I'm just a little behind you, close enough to take your hand. This old body has given up, just as yours has too, and the eviction notice is on its way any day now." Ihlen died that month.

A few months later, Cohen spoke to The New Yorker about his 2016 album "You Want it Darker." "As I approach the end of my life, I have even less and less interest in examining what have got to be very superficial evaluations or opinions about the significance of one's life or one's work," he told the magazine. "There's the element of time, which is powerful, with its incentive to finish up ... The big change is the proximity to death ... My natural thrust is to finish things that I've begun."

Cohen died 17 days after the release of "You Want it Darker," at age 82. It was later revealed that he had been battling cancer, per The New York Times. Cohen's manager, Robert B. Kory, then gave further information about the songwriter's death. "Leonard Cohen died during his sleep following a fall in the middle of the night on Nov. 7," he said in a statement (via The New York Times). "The death was sudden, unexpected and peaceful."