Joyce's Ulysses and Eliot's The Waste Land are rightly hailed as masterpieces – but they unfairly overshadow the year's other great books, writes John Self.

I

In our age of Covid-19 and climate change, it's easy to think that no one has had it tougher than us. But 100 years ago, people thought the same. World War One and the Spanish flu pandemic had each killed tens of millions of people, and the social order in Europe had been overturned. Even in the years before these cataclysmic events, an increasingly technological society – cars, planes, the first radio broadcasts – felt as revolutionary to those born in the 19th Century as the internet does to those born in the 20th.

More like this:

- Ulysses: A classic too sexy for censors

- The only surviving recording of Virginia Woolf

- The world's most misunderstood novel

The response of artists and writers was to remake their work: a way of seeking either to control the strange and uncontrollable, or simply to portray it more truthfully. If the world is chaotic and unsettling, went the reasoning, then the music, art and writing must be too. Spanning several decades, the modernist period gave us the atonal music of Berg and Schoenberg and the Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque.

In literature the response to the challenges and opportunities of the early 20th Century was Modernism – the rejection of traditional linear storytelling and the use of more challenging styles to reflect the new world – and its annus mirabilis is usually seen as 1922. It was an apt time for breakthroughs: the same year saw, among other world-defining events, the appointment of Joseph Stalin as General Secretary of the Communist Party in Russia, the first treatment of diabetes using insulin, and the creation of the BBC. In literary terms, this was the year stamped at one end by James Joyce's novel Ulysses (first published 100 years ago today, on 2 February; Joyce's 40th birthday) and at the other by TS Eliot's book-length poem The Waste Land, published in October. These were books like nothing quite seen before, in their style, scale and ambition: in England the novel in this era was dominated by social realists writing traditional narratives, and poetry by the so-called Georgian movement of pastoral poems in sing-song rhythms.

James Joyce is pictured with Sylvia Beach, who published Ulysses in 1922 through her Paris bookshop, Shakespeare and Company (Credit: Keystone/ Getty Images)

The two books had much in common. Both were determinedly new in subject matter: Ulysses reported on a day in the life of modern Dubliners, going everywhere with them including to the bedroom and the bathroom. The Waste Land addressed the bleak landscape of post-war Europe: "A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many." Both books foregrounded their innovative styles, every page stamped with the author's personality and unusual intelligence. They took a bricolage approach, assembling their texts from multiple voices and viewpoints (Eliot's working title for The Waste Land was He Do the Police in Different Voices). They were comfortable with both high and low culture: Ulysses is structured after The Odyssey, mixes Latin and Greek into its prose, but talks of toilet habits, masturbation and sex (it was the subject of seizures for obscenity on both sides of the Atlantic); in The Waste Land multilingual ostentation sits alongside nursery rhymes and the voice of a pub landlord.

Both, too, are difficult books but filled with beautiful, traditional literary language that anyone can enjoy, from Joyce's "The summer evening had begun to fold the world in its mysterious embrace," to Eliot's "A current under the sea / Picked his bones in whispers". They knew how to please as well as challenge the reader. This, and not just their newness at the time, is why they continue to be read and reread.

Because of books like Ulysses and The Waste Land, 1922 changed the reading public's perception of what literature could be – the poet WH Auden later said that the "climate" had changed. The year deserves its reputation as a moment beyond which nothing would be the same. Yet there is a danger, in rightly celebrating the centenary of these two monuments of modern literature, of allowing their bulk to block our vision. Colm Tóibín exemplified this myopia when, writing about Ulysses last month, he said, bluntly, "The other great literary event of that year was TS Eliot's The Waste Land". There were many other writers producing innovative, daring, satisfying work in 1922 who are not this year being as feted as Joyce and Eliot, perhaps because their work is less showy in its newness, or hides its strangeness under a friendly surface. And most of these writers had views on Ulysses or The Waste Land too.

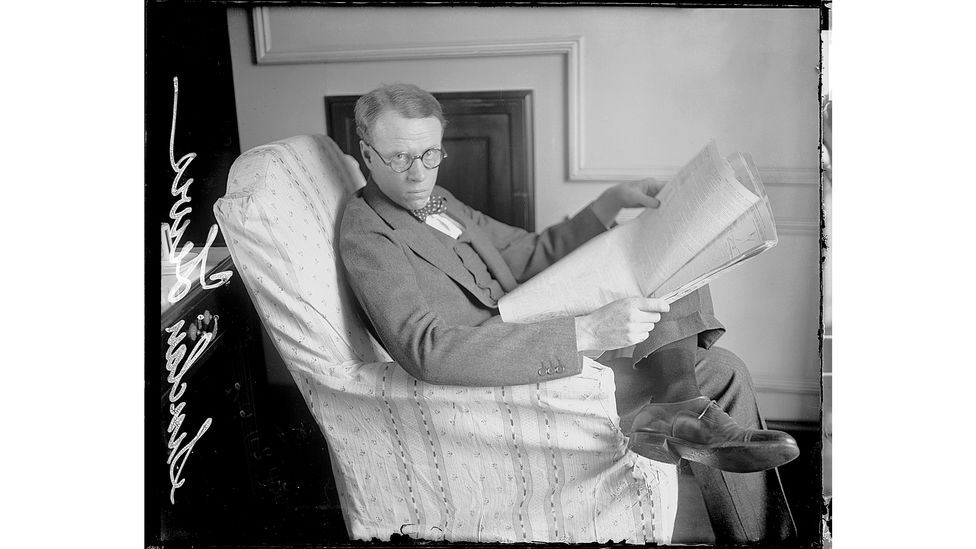

Sinclair Lewis, a prolific and uneven genius of fiction who would go on to become the first American writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, was one of those lukewarm toward Ulysses, calling it the "great white boar". Lewis had his own ground-breaking novel published in 1922. Babbitt was innovative not stylistically but in subject: his self-deceiving, conformist businessman anti-hero George Babbitt was struggling with an emptiness he could not identify, and therefore could not fill. "It was coming to him that all life as he knew it and vigorously pursued it was futile."

Its subject – of the individual's difficulty in identifying our true self apart from the roles and experiences assigned to us – was thoroughly modern, and highly controversial: the president of business association The New York Rotary Club said Sinclair was "a little bit off his trolley". But the book was a huge popular success, selling 250,000 copies in its first edition and making "Babbitt" a byword for a certain kind of blinkered business figure.

Sinclair Lewis's ground-breaking novel Babbitt was published in 1922 (Credit: Chicago History Museum/Getty Images)

Babbitt's exposure of suburban malaise tapped into feelings so powerful and under-represented that it sparked a whole genre of fiction about the hidden misery of successful middle-class men. Its successors include Sloan Wilson's The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955), Richard Yates's Revolutionary Road (1961), Joseph Heller's misanthropic masterpiece Something Happened (1974) and even Bret Easton Ellis's grotesque satire American Psycho (1991).

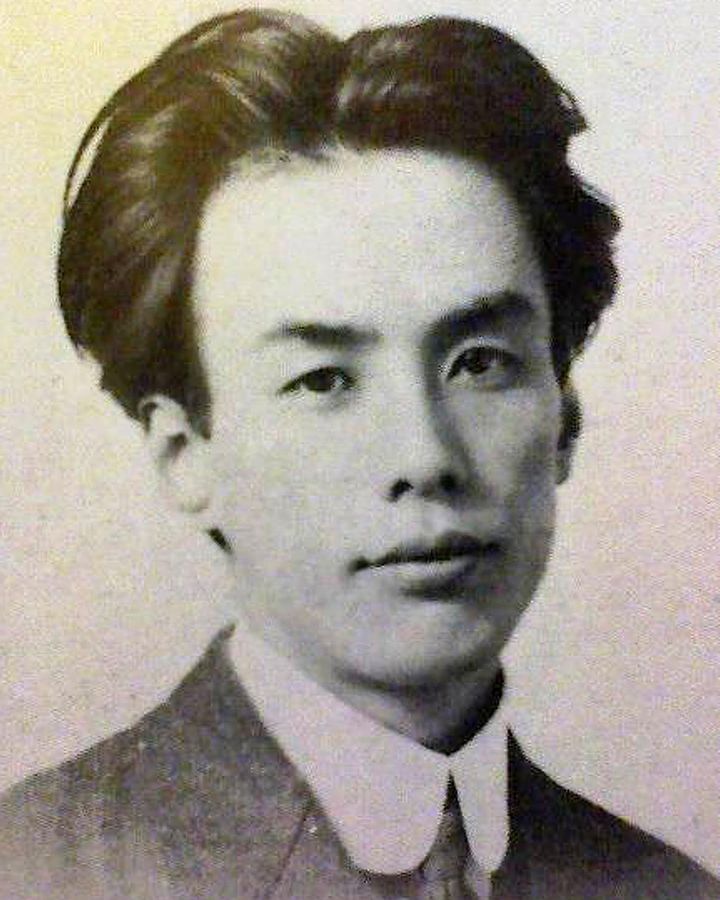

On the other side of the world, in Japan, Ryūnosoke Akutagawa began 1922 by redefining literature in his own way. In January, his story In a Bamboo Grove was published in the new year issue of literary magazine Shinchō. It's best known now as the main source for Akira Kurosawa's film Rashomon, but the story remains a masterwork in its own right. Akutagawa's innovation was to blend old and new at a time when Japan was emerging from centuries of isolationism: he retold a 12th-Century folk tale using a fractured narrative, reporting the murder of a man from numerous different viewpoints and witnesses, several of which are mutually contradictory. This has become a popular way of storytelling because it forces the reader to engage to work out the whole picture, not just in literature (Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire, Tommy Orange's There There) but in cinema: think of films like Pulp Fiction, Gone Girl or The Last Duel.

In a Bamboo Grove challenges the idea that the truth can be definitively known and undermines the concept of the narrator's authority, just as Joyce and Eliot did with their messy, chaotic constructions. Akutagawa's life too was marked with chaos: his mother suffered severe mental illness in the year of his birth and was hidden upstairs until her death; his father later had another child with her sister. In 1927, Akutagawa's sister's house caught fire: her husband, suspected of arson, then killed himself. Akutagawa took his own life a few months later; his death (according to his translator Jay Rubin) was "seen as a symbol of the defeat of bourgeois Modernism."

Ryūnosoke Akutagawa's story In a Bamboo Grove is best known as the source for Akira Kurosawa's classic film Rashomon (Credit: Alamy)

It's true that Modernism was sometimes seen – and not just in Japan – as a middle-class affectation, not least due to the snobbishness of some of its practitioners. Best known among these was Virginia Woolf, whose opinion of Joyce's Ulysses was mixed at best: she found herself at once "amused, stimulated, charmed, interested" and "puzzled, bored, irritated, disillusioned". She was condescending about it too: it was, she said in her diary, "the work of a self-taught working man, and we know how distressing they are".

She went on: "A first rate writer, I mean, respects writing too much to be tricky; startling; doing stunts." Nonetheless she rejected the old and traditional in fiction, favouring "the crashing and the smashing" acts of modern writers. And it was in 1922 that Woolf made her own break with literary tradition, with her novel Jacob's Room, which is her first experimental work and a transition from her earlier, conventional novels to her best-known books Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927). The stunts here were more subdued than in Ulysses, to be sure, but the experiments are unmistakable. From the first page, where a character asks: "Where is that tiresome little boy? I don't see him," to the end, where Jacob's mother and her friend rummage around in his belongings, Jacob is less a presence in the book than an absence. Instead of the title character centre stage, as we're used to, we get more than 200 characters and their fleeting relevance to and impressions of his life. In doing so Woolf paves the way for multiple viewpoints, as Eliot did with The Waste Land, and Akutagawa with In a Bamboo Grove.

Virginia Woolf's 1922 novel Jacob's Room was her first experimental work (Credit: Mondadori via Getty Images)

Eliot, a friend of Woolf's, called Jacob's Room "a remarkable success", and Woolf, who ran The Hogarth Press with her husband Leonard, in her diary early in 1922 noted that Eliot "has written a poem of 40 pages, which we are to print in the autumn". Woolf giving The Waste Land its first standalone publication (even though she was "not sure" how the parts of the poem linked together) was just one example of her role as key connector in modernist circles. Less well-known than Woolf but equally important was May Sinclair, who was admired by Eliot (the feeling was mutual: she was an early advocate for his 1915 poem The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock) and who provided patronage to Ezra Pound, enabling him to be the busy man at the centre of high Modernism.

In 1922 Sinclair, a critic, poet and philosopher as well as a novelist, published Life and Death of Harriett Frean, a short novel that beautifully but brutally depicts the wasted life of the title character. It is an innovative but not difficult book (one critic called Sinclair "the readable modernist"), capturing scenes from Harriett's life in discrete snatches: "an experiment in compression," as she described it in a letter to Sinclair Lewis. A few years after women in England were finally given the right to vote, Harriett's life showed that women's lives remained constrained by society's expectations for them to "act beautifully." Sinclair's eye doesn't blink as she reports on Harriett's life passing as she repeatedly crushes her own prospects for happiness. "Months passed, years passed, going each one a little quicker than the last. And Harriett was 39."

Sinclair's writing was emblematic of the "New Woman" movement after the turn of the century, questioning the traditional roles of women in the family and the economy. Her 1910 novel The Creators: A Comedy, as well as being frank about female sexuality, was the first novel to depict writing as a plausible career for a woman. There's a danger, however, of Sinclair being best remembered not for her own books but for what she said about other people's: in a review of Dorothy Richardson's epic novel cycle Pilgrimage in 1918, she coined the literary term "stream of consciousness". This term has been widely used in the century since – not least when describing the novels of Joyce and Woolf when they tell their stories using a character's internal thoughts and impressions, flowing as seemingly randomly as thoughts do in our own heads. The stream of consciousness technique, wrote Sinclair, enabled Richardson to get "closer to reality than any of our novelists who are trying so desperately to get close".

May Sinclair's writing was symbolic of the "New Woman" movement, which questioned the roles of women in society (Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A determination to be one of the New Women also drove the last of 1922's overlooked geniuses, Katherine Mansfield. She moved from her birthplace New Zealand to London in 1903, and became a central connector in the literary world through sheer force of personality and talent. She had tea with James Joyce in Paris, had a wobbly long-term friendship with Virginia Woolf, and – in the view of Mansfield's biographer Claire Tomalin – caught from DH Lawrence the tuberculosis which would plague her final years and kill her in 1923, at the age of 34. When Mansfield died, Woolf wrote in her diary: "When I began to write, it seemed to me there was no point in writing. Katherine won't read it. Katherine's my rival no longer."

Mansfield was uncompromising in her views of other writers, both modernist – Eliot was "unspeakably dreary" – and traditional, feeling that the exquisite surfaces of EM Forster's fiction lacked substance. "[He] never gets any further than warming the teapot. He's a rare fine hand at that. Feel this teapot. Is it not beautifully warm? Yes, but there ain't going to be no tea." And her review of Woolf's 1919 novel Night and Day is said to have helped spur Woolf into the experiments of Jacob's Room and her later work.

Katherine Mansfield's The Garden Party and Other Stories was her last published work (Credit Keystone/ Getty Images)

Mansfield's own work is best represented in The Garden Party and Other Stories, the last book she published in her lifetime, in 1922. The stories – she never wrote a novel – are fluid, lively and funny, with open-ended plots and a light touch: characters are presented with minimal background information, allowing the reader to fill in the details. Narratives shift perspective, and Mansfield said she wanted to "intensify the so-called small things – so that truly everything is significant." As well as being modern in style, the opening story At the Bay, seems very timely right now when one character reflects on the horror of going back to the office: "I'm like an insect that's flown into a room of its own accord – I dash against the walls, dash against the windows, flop against the ceiling, do everything on God's earth, in fact, except fly out again."

The stories and books of these writers from 1922 – from Mansfield, Sinclair, Woolf, Lewis and Akutagawa – wear their newness and their brilliance less forcefully than Eliot's or Joyce's do. (Eliot, with faint praise, said that Mansfield's writing "handled perfectly the minimum material – it is what I believe would be called feminine".) But they were equally important responses to tumultuous years, and we can read their influence in today's writing just as clearly, both in style and subject matter. The practitioners were not always so confident. Mansfield feared that "I shall not be 'fashionable' long. They will find me out; they will be disgusted; they will shiver in dismay". And Virginia Woolf, near the end of 1922 – on Christmas Day – wrote to her friend Gerald Brenan, saying she worried that their generation of writers would be just a stepping stone for the next: "For I agree with you that nothing is going to be achieved by us. Fragments – paragraphs – a page, perhaps: but no more." She was, as we can happily see 100 years later, entirely wrong.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.