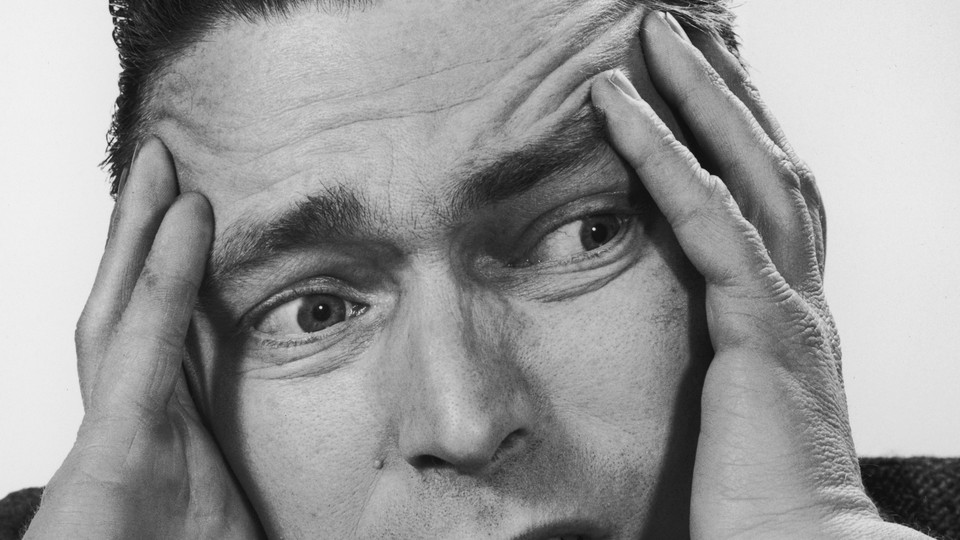

The internet’s new social norms mean there are countless new ways to be humiliated.

Sign up for Caleb’s newsletter here.

Gee whiz. There’s nothing like a good interjection: Those little words or phrases that litter our language (Yippee!!) for no semantic reason beyond the need to express an emotion too deep to be contained by classical grammar. You’re just going along, reading some writing, and BAM!—an interjection takes you to the next level of visceral understanding. Shit … you can keep your verbs and nouns. Big deal. Just leave me those Booyahs and Cowabungas and Good griefs and Duh, duhs, and I’ll be a happy man. Defiant and independent, interjections don’t even change morphologically for other words, for heaven’s sake. They slip between the cracks of a sentence to spice up the experience, like syntactic hot sauce. They also have the unique power to stand alone in a sentence. Bravo! Mamma mia. My, my. And, indeed, there may be no word that speaks to the deepest, most inexpressible feeling of the internet than the interjection Cringe.

Though it has reached peak usage with the internet age, cringe has been around since the Old English cringan, which meant, variously, “to fall, to yield in battle, to give way, to become bent, to curl up.” It’s the same word that gave us crinkle. As anyone who has recently seen a photo from their pubescent years can tell you, the modern sense of cringe is not too different. To cringe at something is to yield a battle of the soul—and instinctively to contort one’s body to match. Cringan evolved into its current form, cringe, in 16th-century Middle English, when it came to mean “to bend or crouch in embarrassment, servility or fear” (see: Robert Greene’s 1591 pamphlet describing a “fellow courteously making a low cringe”). By the 19th century it had been generalized into the current meaning: “to recoil in embarrassment, shame or fear.”

Read: How a crossword editor plays Wordle

Cringe gained new relevance online. The latter half of the 20th century saw the rise of cringe comedy, in which an obnoxious and/or socially awkward protagonist wreaks havoc, typically in a documentary or mockumentary setting. From Curb Your Enthusiasm to The Office, cringe comedy became a staple of modern TV. Cringe soon proliferated on social media, and so perfectly captured a contemporary feeling that it has been used as a verb (“I’m cringing at that post”), adjective (“Such a cringe post”), collective noun (“Stop posting cringe”) and, yes, even the holiest of holies, an interjection: “Did you see that post? Cringe!”

Cringe’s newfound versatility reflects its special relevance to life today. With a new form of public space—the virtual—comes the navigation of new social norms and, consequently, new ways to be humiliated. Our instinct to cringe reinforces the new norms of online social behavior on a bodily level. The proliferation of online public embarrassment necessitates a new, informal way to describe it—and in skulks cringe, a word already well suited to express instinctual contortions of public shame. For our Tuesday clue, I wanted to feature my favorite interjectional usage, which cuts through grammar to the emotional core of the word: “That’s awkward and embarrassing.”