The old adage tells us opposites attract. Not only is it wrong – but it may be less true than ever.

P

People have long lived by the adage ‘opposites attract’ – the introvert will fall for the extrovert, the bad boy for the straight-A student. This belief is lodged in popular culture, and has been for years.

But while many people are quick to agree that opposites attract, and may even jump to an example in their own life, multiple researchers have debunked the idea throughout the years. “The research is pretty clear, actually, that it’s not true,” says California-based clinical psychologist Ramani Durvasula, an expert in toxic relationships. “People who have shared interests, temperaments and all that do tend to be more likely to date.”

Indeed, various studies have shown friends and romantic partners tend to share core beliefs, values and hobbies; people tend to be attracted to or trust those with similar physical features; and some research suggests people go for others with like personalities. Essentially, both researchers and psychologists largely say people have long been drawn to those with shared traits, beliefs and interests.

There's also a body of evidence to suggest that opposites repel – particularly around views and values. And in an increasingly divided social, political and cultural climate in countries across the world, it's possible that we’re even less likely to fall for someone who thinks very differently to us. Factors like social media indicate it’s becoming significantly easier for daters to jump into ‘bubbles’ of like-minded others, leaving the idea of ‘opposites attract’ more outdated than ever.

Seeing eye-to-eye – even if it looks otherwise

It’s difficult to exactly pinpoint the origin of the saying ‘opposites attract’, but American sociologist Robert F Winch suggested it in a 1954 paper in the American Sociological Review. His research focused on “complementary needs in mate selection” – the idea that people sought out partners who had certain qualities they lacked (like the introvert choosing the extrovert, perhaps as a way for the introvert to benefit from the extrovert’s influence).

Close on the heels of Winch’s research, however, other scientists began drawing different conclusions. Less than a decade later, another US-based social psychology researcher, Donn Byrne, challenged the opposites-attract hypothesis with his own paper. Byrne hypothesised that “a stranger who is known to have attitudes similar to those of the subject is better liked than a stranger with attitudes dissimilar to those of the subject [and] is judged to be more intelligent, better informed, more moral, and better adjusted”. His research supported both hypotheses.

“That was the beginning,” says Angela Bahn, associate psychology professor at Wellesley College, US. “Ever since, there’s been really strong, widespread evidence for similarity attraction.”

Bahn found this in her own 2017 study, in which researchers met pairs of people by approaching them in public spaces in Massachusetts. They observed that similarity between the pairs was statistically significant on “86% of variables measured”, including attitudes, values, recreational activities and substance use. More specifically, pairs of friends and romantic partners matched closely on attitudes about gay marriage, abortion, the government’s role in citizens’ lives and the importance of religion.

Still, there are plenty of reasons why it may seem like opposites attract, such as superficial differences that make people appear more opposed than they really are. A “straight-laced accountant” and “disinhibited artist”, for example, may look like an antithetical couple, suggests Durvasula – but “their values, whether that's around family [or] political ideology,” would likely be similar.

There's a body of evidence to suggest we prefer people who think similarly to us, particularly when it comes to views and values (Credit: Getty)

Interestingly, personality remains one area where conclusions are less straightforward. In Bahn’s study, for example, pairs displayed “lower levels of similarity” in personality, specifically when it came to what are known as the “big five” personality traits – openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Bahn explains that, for example, "two people who are highly dominant are not going to work well together, so that’s the one area where complementarity, which you can spin as ‘opposites attract’, is much more common”.

But another 2017 study by University College London social psychology lecturer Youyou Wu came up with different findings. Looking at the Facebook profiles of roughly 1,000 couples and 50,000 pairs of friends, Wu and colleagues “showed that there is similarity stronger than was previously found… for all five personality traits” among pairs – more indication that opposites may indeed not attract, even if it may seem the case.

Dating apps encourage seeking similar partners

This isn’t to say, however, that people with polarised values and views won’t find success together; it happens, of course, and there can be benefits to disagreement – or even fundamental opposition – in couples.

Paris-based Ipek Kucuk, 29, a dating and trends expert at dating app Happn, says she recently went from dating a person with whom she “agreed on everything” to someone who has alternate perspectives on hot-button issues like vaccination and religion. “Before I broke up with my ex, I didn't know how bored I was,” says Kucuk. “While it was quite a roller coaster of conversations with my current partner because he shocked me with some of his opinions, it really made me grow… it broadens my perspective. I really appreciate that.”

However, Kucuk says she holds certain beliefs that she must share with her intimate partner – like feminism and the support of LGBTQ rights. And many others seem to have the same preference.

The role technology plays in how we interact today makes it more likely the people we meet will have similar views to us (Credit: Getty)

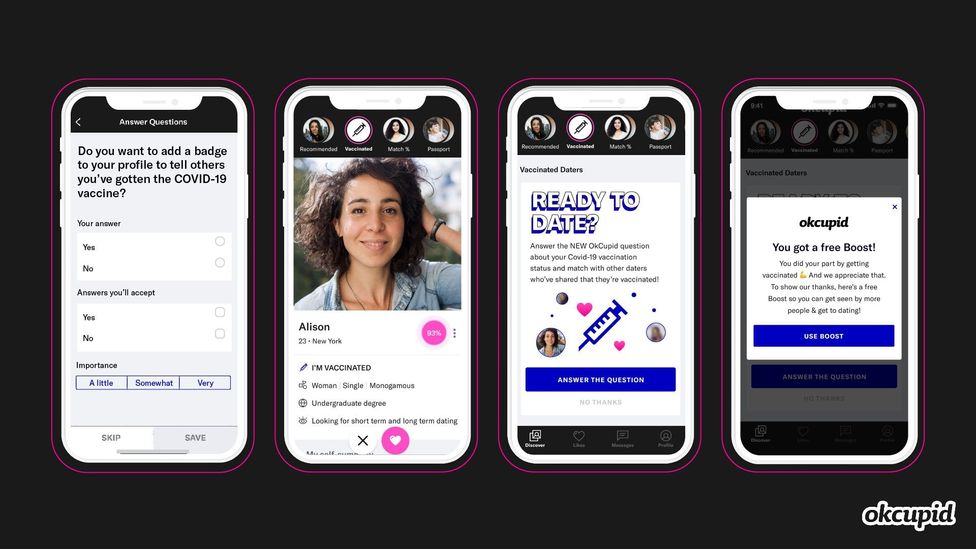

Today, sharing political views has been essential to couples matching up. In one example, mentions of “Black Lives Matter” (or BLM) increased by 55 times in 2020 on the dating app Tinder, indicating that people were unwilling to compromise on partners who didn’t share their most crucial convictions. After OkCupid released a badge users could put on their profiles to show their support of BLM, users who included the badge became two times more likely to match with other users who had the badge, an OkCupid representative told BBC Worklife over email.

The outsized cultural influence of social media – and its algorithms that connect people with similar beliefs – may be pushing daters even more towards those who share the same views and attitudes.

As Wu explains, several dating apps recommend people in your social media networks, or based on shared ‘likes’ on Facebook or follows on Twitter. And roughly 48% of US adults between ages 18 and 29 used dating apps, per a 2019 Pew Research study. “Based on our research showing that friends are similar in personality to begin with,” says Wu, the people using dating apps that recommend friends of friends are essentially just meeting more people like themselves.

Dating apps that cater to people with specific views have also been cropping up over the last several years, specifically surrounding the divisive 2016 presidential election in the US. Apps that debuted around that time targeting politically conservative users included Righter, Conservatives Only and Donald Daters. Two years after the election, Bumble instituted a ‘filtering’ feature that allowed users to pass over profiles of people who didn’t fit their political and lifestyle preferences.

“It's easy to connect with people who you agree with online,” says Bahn. “The algorithms on social media platforms show us things that they think we're going to agree with already.”

Online dating services appear to embrace this – it’s a feature, not a bug. According to the OkCupid spokesperson, “OkCupid is notorious for helping people connect on social and political issues due to our questions-based algorithm.” She further specified issues the dating site helps people “match on”: reproductive rights, gun control, the Covid-19 vaccine and BLM. The company’s release of badges, like the BLM badge and a “Climate Change Advocate” badge, to help people easily find others who share their key beliefs, suggests that this trend is only growing.

Now, the online networks and sites many of us use to find friends, dates and, ultimately, love are all nudging us towards people who seem to think similarly to us. That’s not all bad – the plethora of data showing the high percentage of couples who share views and values suggests it’s a good indicator of a lasting relationship. But there are downsides too; if we only date people who think just like us, we’re less likely to have the kind of conversations Kucuk is enjoying with her partner – the debates that challenge our assumptions and perhaps even open our eyes to different world views. Yet given the prevalence and power of technology – and the fact that opposites didn’t exactly attract to begin with – the adage may well be on its way to obsolescence.