Creative nonfiction can take many forms, be it a meandering lyric essay or longform narrative journalism, and its practitioners don’t always agree on how creative one can be with the truth. When a writer does decide to adhere to fact, they have at their disposal two main subjects—the self and everything outside the self. But even when nonfiction writers plan to turn their gaze outward, what they discover can have a tricky way of bringing them back to themselves. Exploring the world through interviews, travel, and library stacks can help clarify facets of experience that might have seemed singular or ordinary. Put another way, when writers get away from what’s going on inside their head, they just might see their own life in a new light and find something universal in the personal.

What results is what you might call a “backdoor memoir”: a book that seems at first to focus on an outside phenomenon—the reproductive cycle of eels, say, or the love letters of a Southern Gothic novelist, or the oil-and-gas industry in the North Sea—but ends up revealing just as much about its author as it does its topic. In the list below, nine authors’ outward exploration of their subject complement their inward gaze. Both strands of inquiry are necessary to fully share the stories they set out to tell.

Coming Into the Country, by John McPhee

McPhee, a pioneer of creative nonfiction and a prolific chronicler of the natural world, has published more than 30 books. Some recent works, such as Draft No. 4, invite readers inside his head as he outlines his writing process. But of the early titles that made his name, Coming Into the Country, from 1976, is the one in which McPhee is most a character. A detail-rich chronicle of McPhee’s travels in Alaska, it explores the frontier myth and remote terrain. McPhee serves as the reader’s guide down rivers in the Brooks Range, through urban settlements, and into the bush of the upper Yukon (known by its settlers as “the country”). His first-person account also offers the sort of self-portrait that is missing from many of his other, more detached narratives. In the last section, about “the country,” McPhee admits that though he “may have liked places that are wild and been quickened all my days just by the sound of the word,” camping out down by the Yukon River teaches him that he had never before imagined wilderness like this.

Read: The terror and tedium of living like Thoreau

The Women, by Hilton Als

Published in 1996, Als’s first book braids the cultural criticism that won him a Pulitzer Prize in 2017 with memoir to deconstruct how the intersection of race and sexual identity can circumscribe a person’s life. The Women unfolds in three portraits, with his own self-investigations threaded throughout. First, we meet Als’s mother, who emigrated from Barbados to New York and called herself a “Negress”—a long-suffering Black woman who never spoke of the burdens she carried; Als once used the term to identify himself too. The two other portraits—of Dorothy Dean, a Black, Harvard-educated socialite in 1950s and ’60s white gay New York City, and Owen Dodson, a Black poet and dramatist who Als writes “did not consider himself to be” a man and who was Als’s mentor and lover—add further nuance to the concept of “Negress” and to Als’s sense of self. He compellingly pushes back against his mother’s self-abnegation, telling her story in a way that she refused to do herself. In the process, he builds a narrative outside the one that the women in his family built for him.

Hiroshima in the Morning, by Rahna Reiko Rizzuto

In June 2001, Rizzuto left Brooklyn and arrived in Hiroshima on a six-month research fellowship with the goal of interviewing the remaining survivors of the atomic bombing there, or hibakusha. She had planned to write a novel based on her research, and she would eventually, but what she discovered in Hiroshima—about the construction of memory and history, her Japanese family, and her marriage and motherhood—pushed her down the path of what would become Hiroshima in the Morning. Rizzuto was still in Japan on 9/11, and in the aftermath, the hibakusha began to drop their carefully rehearsed narratives of the bombing, seeing her as a fellow traveler in tragedy. Through the survivors’ testimonies and diaristic reflections on her travels in Japan, Rizzuto realizes “that we rewrite ourselves with every heartbeat.”

Read: Preserving the horrors of Hiroshima

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, by Robin Wall Kimmerer

In this collection, Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, attempts to use stories as “medicine for our broken relationship with earth,” she writes. The 31 essays highlight the places where Indigenous and scientific understandings of botany meet, taking Kimmerer’s work at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, where she founded the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, outside the walls of the academy. Kimmerer grounds the lessons that plants teach us in her own experience. Readers learn, for instance, about her connection to pecans—her grandpa collected them in his pant legs as they fell off trees in 1895 Oklahoma, after her people were violently removed from their land near Lake Michigan—and follow her to those pecan groves when her family returns to the state for the Potawatomi Gathering of Nations. In moving from stories of her upbringing to broader meditations on the necessity of ecological consciousness, Kimmerer reflects on her own relationship to nature in order to inspire the same in the reader.

The Book of Eels: Our Enduring Fascination With the Most Mysterious Creature in the Natural World, by Patrik Svensson

Svensson’s book initially appears as though it will be a scientific exploration of, well, eels. The fish appear to be sexless; how they reproduce has long been a mystery, and that question seems to drive the cultural journalist’s inquiry. But underneath his fascination with eels lies the story of his relationship with his late father, a road paver with whom Svensson bonded over nighttime eel-fishing trips in rural Sweden. “I can’t recall us ever talking about anything other than eels and how to best catch them, down there by the stream,” Svensson writes of these trips. “I can’t remember us speaking at all.” As he jumps between natural and personal history, pulling in thinkers as disparate as Aristotle and the marine biologists Rachel Carson and Johannes Schmidt, Svensson considers not just the elusive eel but the conundrums of human life. Ultimately, The Book of Eels is a reckoning with how to face death.

My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, by Jenn Shapland

Shapland’s unusual title refers to her book’s dual functions: uncovering how the novelist Carson McCullers, a chronicler of outsiderness, was kept in the closet after her death, and examining Shapland’s own life as a lesbian writer. When she was 25, Shapland interned at the Harry Ransom Center archives at the University of Texas at Austin, which holds McCullers’s papers and effects. There, Shapland stumbled on love letters between McCullers and a woman with whom she had had an affair. What followed was a sort of obsession with and possession by McCullers, as Shapland experienced a belated coming-of-age in her own sexual identity that brought her to this book—a project she describes as taking place “in the fluid distance between the writer and her subject, in the fashioning of a self, in all its permutations, on the page.” Through her accounting of McCullers’s life (and her own), Shapland argues that the author’s work must be understood through her lesbian identity.

The Undocumented Americans, by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

When she was a 21-year-old Harvard senior, Cornejo Villavicencio was asked to write a memoir. She had just published an essay about being an undocumented immigrant from Ecuador and was angry at the inquiries she got from agents, who she says wanted her to tell a sob story about migration. Instead, years later, Cornejo Villavicencio traveled to Staten Island, New York; Miami; Flint, Michigan; and New Haven, Connecticut, to “tell the stories of people who work as day laborers, housekeepers, construction workers … people who don’t inspire hashtags or T-shirts”—people she would come to see as her chosen family, who all struggle to eke out a living. Although she pushed back against the kind of story agents wanted her to write, there is ample mining of the personal here. Cornejo Villavicencio’s stories of connecting with former Ground Zero cleanup workers, for instance, return her to her family’s own days following 9/11, when her father, the family’s breadwinner, lost his job—and his identity—as a taxi driver after a new law under then-Governor George Pataki made it practically impossible for undocumented immigrants to renew or acquire a driver’s license. In The Undocumented Americans, Cornejo Villavicencio succeeds not just at making her subjects stand out through vivid details but at grappling with questions of familial duty and survival.

Read: What isolation does to undocumented immigrants

Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements, by Jay Kirk

Avoid the Day starts out as a journey in search of a missing text: the handwritten manuscript of the Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Béla Bartók’s third string quartet. Kirk begins by retracing Bartók’s travels through Transylvania, where he recorded peasants singing folk songs on a phonograph in order to transmute what he saw as their “essence” into his own work. But Kirk starts to lose the thread in Romania as he writes himself into another Bartók composition, the “Cantata Profana”—the composer’s most intimate work, about a cursed father and his sons, something Kirk can relate to all too well. While he’s chasing Bartók, he’s also running away from the imminent death of his difficult pastor father, and his fear. In the final act, he escapes Transylvania to accompany an old friend, a documentary filmmaker, on a cruise of the Arctic Circle, where they shoot a horror flick. Of course, you can’t outrun the churning whirlpool of grief, and eventually Kirk is forced to “look straight into the vortex,” he writes.

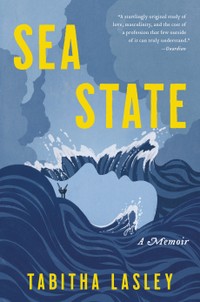

Sea State, by Tabitha Lasley

After Lasley’s laptop containing four years’ worth of work on a novel about oil rigs was stolen from her London apartment, she broke up with her boyfriend and moved to Aberdeen, Scotland. There, she spent six months with the men who work for weeks and months at a time on oil and gas rigs in the North Sea, many miles from civilization. On the second night, though, she slept with one of her sources, a married rigger she refers to by the pseudonym Caden. This breach of ethics ends up making Sea State a far more interesting book than the distanced, sociological reportage on riggers that Lasley had planned. The hybrid work of memoir and unconventional journalism chronicles Lasley’s doomed romance with Caden alongside a consideration of the dangers of a life of oil extraction. Along the way, she learns not to trust her assumptions about men like Caden, places like Aberdeen, and women like herself.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.