Sex sells – and the message couldn’t have been any clearer when it came to advertising in post-revolutionary Mexican. Images of beautiful people served a multitude of purposes: a nationalistic one to quite blatantly plug the new regime, that of a new bountiful and fertile country, modern, productive and populated by good-looking folks from a rich historical pas – as well as to flog every product and service under the Mexican sun and beyond. The medium for this enlightened show was the printed calendar, mass produced for the masses who, throughout their history, have placed great significance on the days, months and years. These vivid calendars have possibly been some of the most noticed, yet least recognized of the visual arts.

Let’s take a giant step back into Mexican history. You must’ve heard about the Aztecs’ famous sacred ceremonial timekeeping stones based on the Mayan calendar; how they measured time with a super sophisticated triple calendar system which followed the movements of celestial bodies and listed important religious festivals and sacred dates.

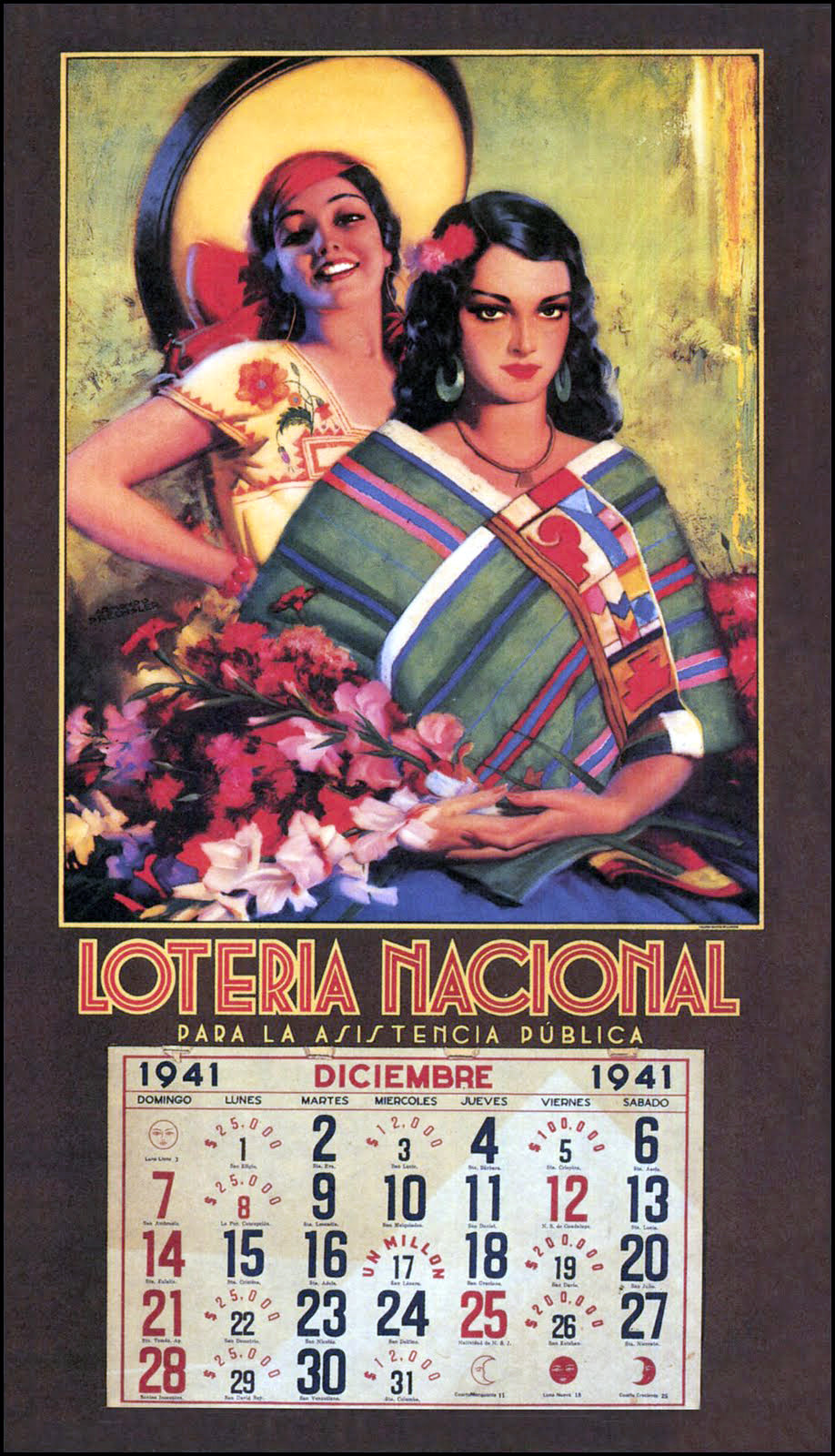

Not only was each day in the calendar given a unique combination of a name and a number, but individual days and periods of days were given their own gods in the calendar. The face of Mexican calendars may have changed drastically since the time of the ancient Aztecs’ stones, but these iconic 20th century wall-hanging date charts with their dramatic, glossy and epic depictions of Mexican beauty, life and culture, would become an intrinsic and much-adored part of the Mexican cultural heritage between the 1930s and 1960s.

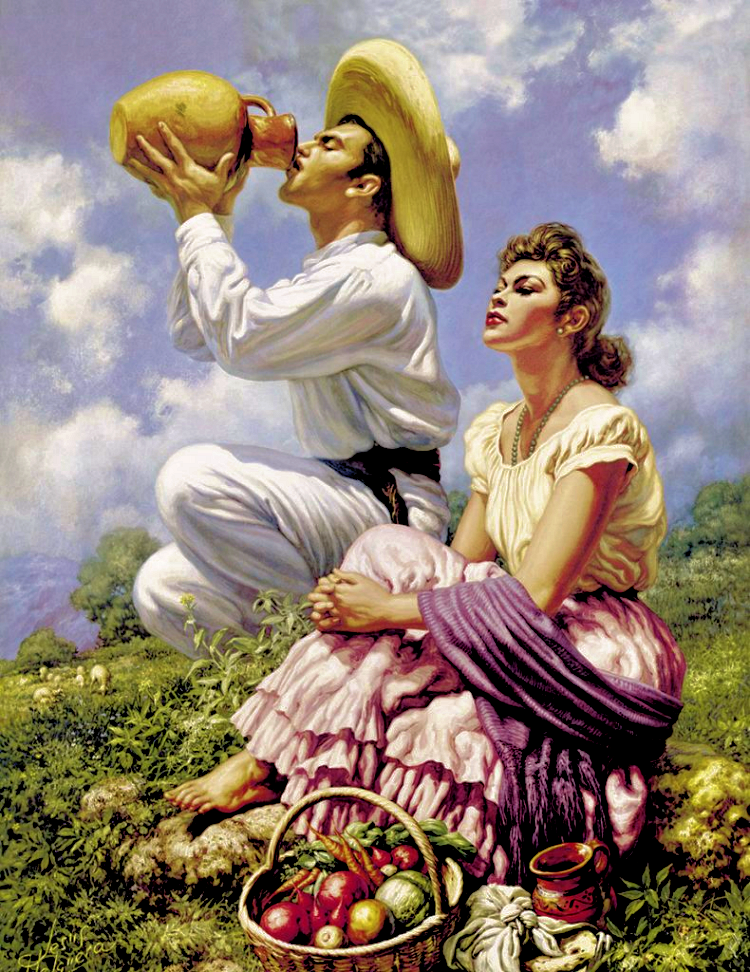

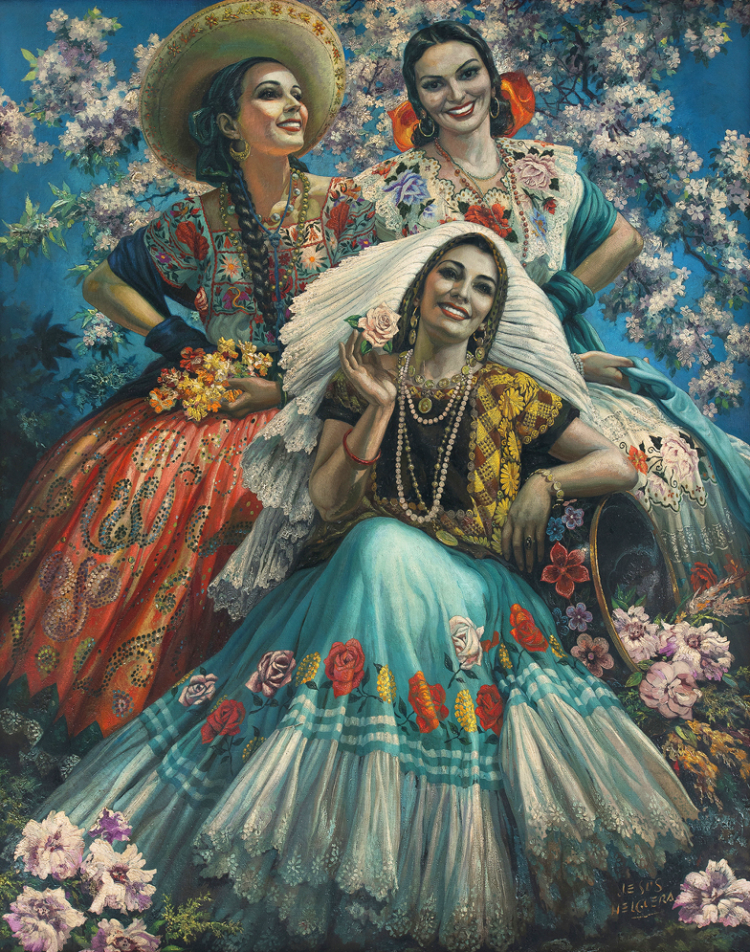

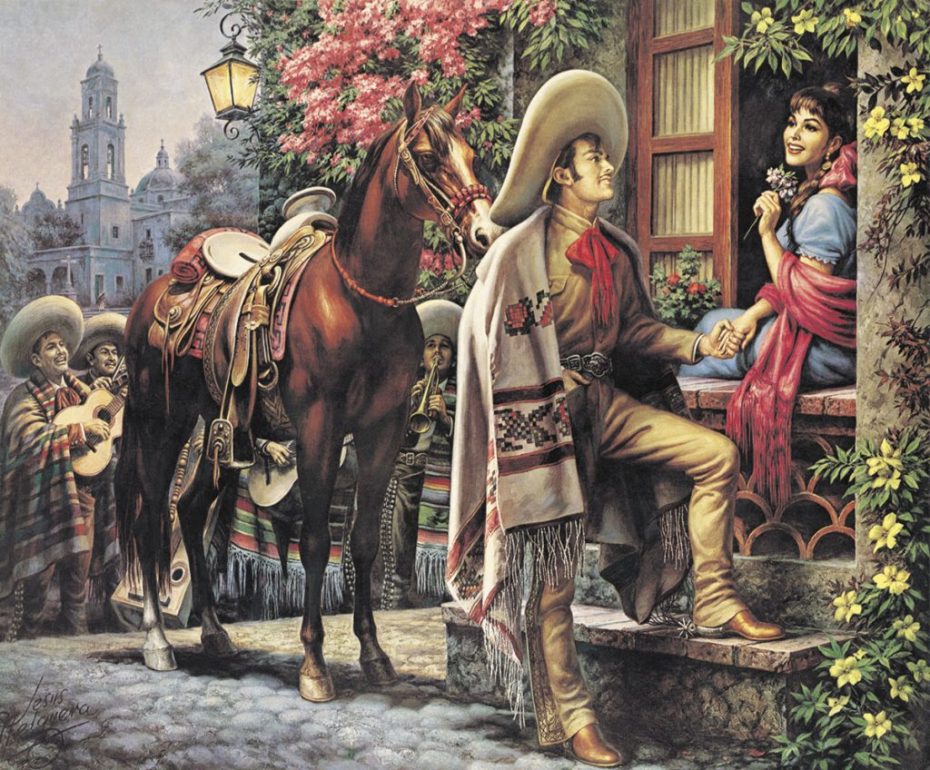

The Mexican calendar girl is both the gorgeous hoop-ear-ringed Aztec princess and the sexy gun-wielding female revolutionary with not as much as a hair out of place. She’s the voluptuous brunette carrying baskets overflowing with fruit and flowers, the doe-eyed señorita in her frilly Tehuana blouse looking adoringly into the eyes of her perfectly chiselled beau. Whilst the revolution may have sought a total Mexican image, this was mostly limited to setting and dress.

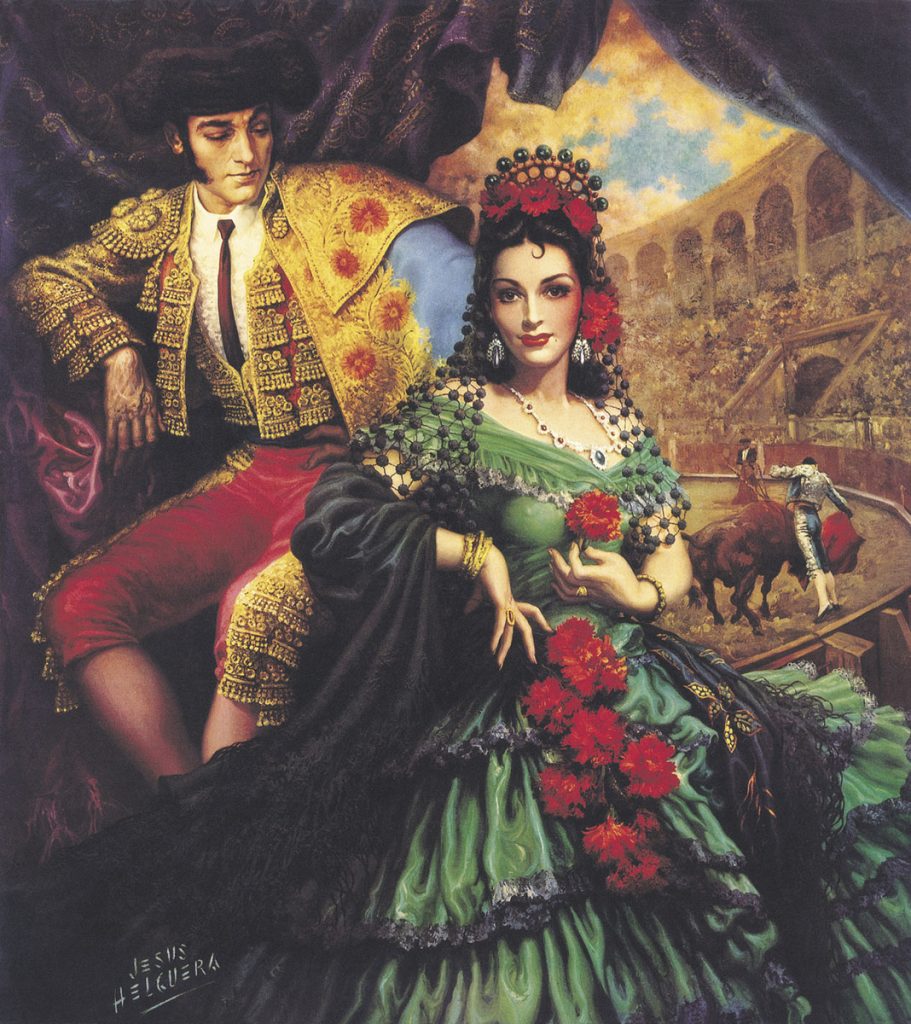

The physical appearance of the calendar girls was ironically based on the European or American concept of beauty – paler skin, high cheekbones, large eyes, long legs, a modern hairstyle and the likes which, to this day, remains the ideals for Mexican beauty (possibly a hang-up from the Spanish past). Very often the faces of the subjects would be modelled on a famous movie star such as Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland, Mexico’s silver screen sweetheart María Félix or Vivien Leigh, whose likenesses stared out from under a broad sombrero or from behind a traditional Tehuana shawl.

Most of these paintings took their cue from earlier European art, the grand Rennaissance compositions and their idyllic landscapes. Perhaps overly romantic, unmistakeably corny and deeply nostalgic, the calendar pictures adorned the rich chocolate box of Mexican culture with its abundance of important dates that had to be remembered and planned for. From ‘The Day of the Dead’ and the Battle of Puebla to the dozens of saintly days, all needed flagging.

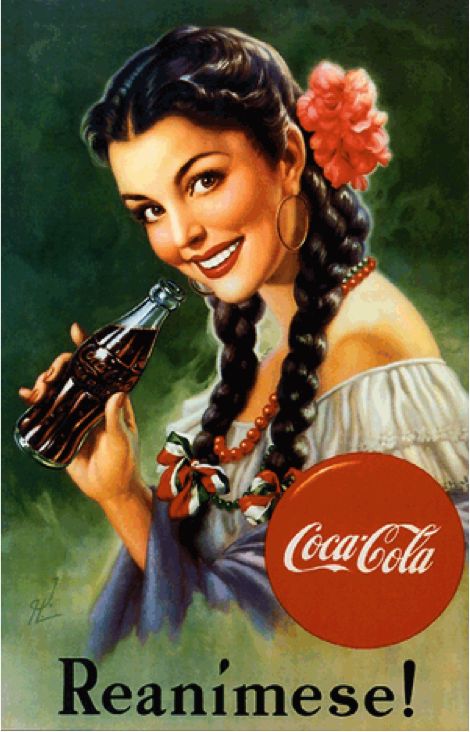

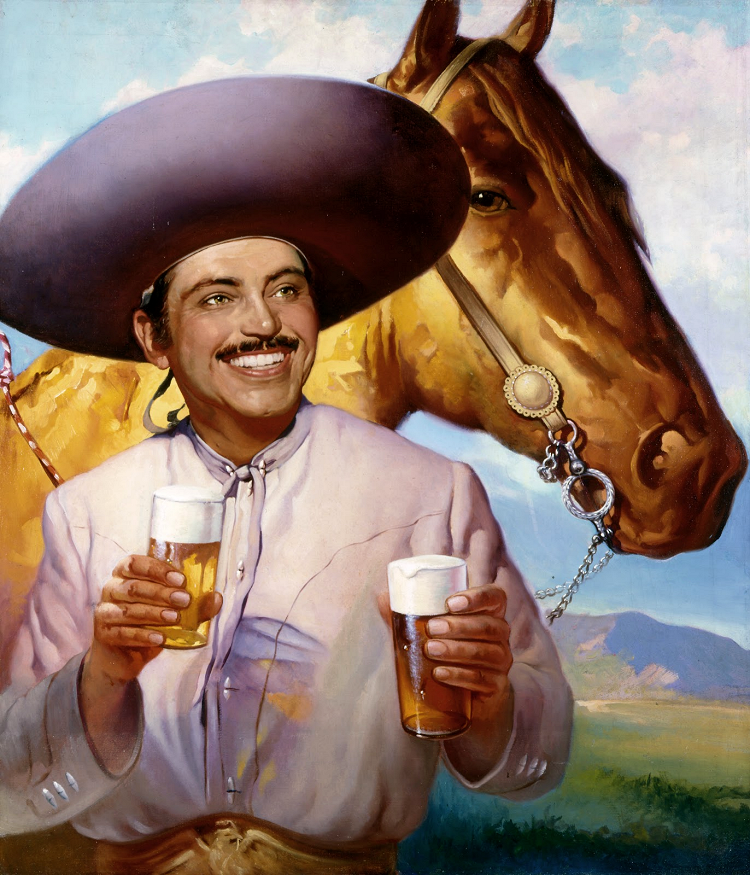

Wall calendars faithfully marked births, celebrations, deaths and even the all-important phases of the moon, but they were also the vehicle to advertise products and promote the new state to the far-flung corners of Mexico and beyond. They conveyed idyllic, stage-managed snapshots of a proud Mexican universe – young, romantic, sensual, patriotic and ready to celebrate their culture. Such is the allure of these scenes, to this day, that we all want to be part of that sentimental, wholesome and exciting picture-perfect world. But don’t be fooled by the comfortingly kitsch appearance – every aspect, from the colour, content and details of the composition to the allegorical and metaphorical connotations, were carefully stage-managed to send an enticing retail message to sell chocolates, cigarettes, beer or tequila.

Commercial printing arrived in Mexico in the 19th century, but the first true calendars weren’t printed until 1935, by the company Enseñanza Objetiva who employed esteemed Mexican painters like Jesus Helguera, Antonia Gomez and Eduardo Cataño to create the artwork. The revolution had increased urbanization and demand and this new consumer class craved not only local products like cigarettes, soda, chocolate, tequila and beer, but also ‘goodies’ imported from the United States such as Coca Cola, light bulbs, car tyres and radios. Hypnotized by the alluring colourful and idyllic calendar images, the supporting advertisements seduced the ‘new’ Mexican to aspire to a higher standard of living and desire the luxuries they saw flaunted in front of them. As a ‘bonus’, the paintings would also serve to subliminally convey aspirational cultural and political messages. The baskets of fruit and flowers, the capacious pots, the modern tractors in the fields and the guns across the breasts of beautiful revolutionaries not only fostered national pride but sent a message to the rest of the world that Mexico was beautiful, modern, prosperous and open for business.

The early 1920s Post-Revolutionary government of President Alvaro Obregon and in particular his then-minister of Public Education, Jose Vasconcelos, went out of their way to instill a sense of nationalistic pride in all things Mexican. A national arts resource would be created by dispatching writers, photographers and artists on funded missions to the villages, markets and farms across the land to record daily life and culture. Photographers like Luis Marquez returned with thousands of original images of remote Mexico, which artists would then rent to recreate their oil paintings.

Jesús Helguera was perhaps the most prolific artist of the Mexican calendar era with a legacy of over 600 original artworks. He would capture the allure of the impossibly irresistible Aztec ‘princesses’ and godlike stacked warriors alike, all superimposed on backdrops of epic Mexican mountains, backlit billowing clouds, elysian fields and cascading waters. Very often it was his wife and children who posed for these ghosted worlds. José Bribiesca Ruvalcaba was another noteworthy artist who produced a vast output for the Galas Printing Press of Mexico. His offerings were less landscape and more figurative, featuring many a leggy ladies. His most famous work is ‘Moctezuma’s Daughter’, Aztec goes to Hollywood.

These calendars became the ultimate tool, an ingenious way of swaying and seducing – sometimes subliminal and covert, at other times blatant and overt. These spectacular bursts of cultural and consumer propaganda were cleverly conceived to find pride of place over the mantelpiece, ever present and always in eyeshot, a necessity for daily planning. Many of calendars would be ‘exclusive’, commissioned by large companies to advertise only their soap or tequila or cigarettes. The best artists would be hired with the product specifications or the name of a store emblazoned across the artwork.

The rise of film and photography in the late 1950s spelled the end of the painted calendar. It was far more costly to paint these realistic pictures than to photograph similarly staged scenes, and overnight, calendar artists became obsolete. Today there are still a few companies promoting calendar art, most notably Calendarios Landin in Guanajuato, who owns the rights to Jesus Helgueras’ paintings. In Mexico City, a local blog found the last news stand selling Mexican calendars which once would have been found on every street corner.

Mexico wanted a new start after the turmoil of revolution and what would be a better way than to use its rich cultural history, diversity and most of all, its spectacular beauty. The gorgeous girls, idyllic landscapes, abundant harvests and revolutionary feats could all work together through the medium of a humble composite calendar illustration to promote this brave new state, not just to Mexico, but the world. Advantageous to the advertising companies and a delight for the consumer (not to mention promoting the national myths), this inexpensive print was all-powerful for decades. Not only part of the Mexican memory, we all shared the Mexican dream through these treasured images. Art to promote nationalism has had many guises, that of Mexico’s calendars are perhaps the most memorable and endearing.