Photography by and of *das gemeine Volk.*

Anthony Morganti is one of my most trusted and valued online mentors, the person I turn to first and more than any other. His newsletter discussed vernacular photography this week, something I had never heard of, nor had Tony.

Excerpted from Morganti Online Photography Training Weekly Newsletter #197.

This week, I learned about a type of photography I never heard of before –

Vernacular Photography.Included in the vernacular of photographs are the vast majority of images most of us take, day in, and day out.

Snapshots.

Pictures of our family are most often associated with this type of imagery –

such as the picture above of my mother, taken by my Aunt Mary many years

before I came into this world. Additionally, the past few weeks I shared, in this

newsletter, pictures of my sons — those are vernacular photographs.Vernacular photography isn’t limited to family snapshots. Our horrid school

pictures are considered vernacular as well as portraiture from cookie-cutter

portraitists such as Olan Mills, J.C. Penny, and Lifetouch. Driver license photos as well as any I.D. photograph are vernacular. Standard, run-of-the-mill wedding photography is vernacular. Vernacular are those functional photographs we all take, see, and use every day.But, are they museum-worthy?

Back to the picture above of my mother — aesthetically, it’s pleasing to me

because that’s my mom but technically, it’s a disaster. Bad framing. Crooked

horizon. It appears to have been lacking in a good archival storage method. But, it’s still beautiful. It has an aesthetic charm that transcends my mother the person in that it projects a time, a place, a feeling to anyone that looks at it.John Szarkowski, whom I’ve mentioned many times in this space was one of the first to recognize that snapshots could be, and are so much more than functional — they could be a type of photographic art in their own way and he was one of the first to organize vernacular photographic exhibitions via his position at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

So, try to look at those everyday snapshots in a different way. You might have

had an aunt, who over 70 years ago, unbenounced to her, was creating art with the click of a button. — Anthony Morganti, Feb 21, 2022

It is a lovely picture, flaws notwithstanding. I like the gentle S-curve of her body, the soft swirl of her skirt in the breeze. She is relaxed and contemplative, on a warm excursion to the beach. We wouldn’t know who she is except for Tony identifying her, but it would be an attractive picture regardless. Snapshots of entirely unknown people going back to the dawn of photography in the 1840s are bought and sold specifically because they have that ethereal beauty and because they are literal slices of time preserved. We can see what our closest ancestors looked like, how they dressed, where they lived, how they lived, thanks to a technology that is not yet 200 years old.

ver·nac·u·lar

/vərˈnakyələr/

noun

the language or dialect spoken by the ordinary people in a particular country or region:

“he wrote in the vernacular to reach a larger audience”

Photography in the vernacular is the visual language spoken by ordinary people.

not long ago published this piece on an unusual tintype she acquired:

Cobie is fascinated by all things photographic, not limited to pictures/art made only with cameras. She is mindful of the history embedded in a photograph, no matter its provenance, where it was taken, or who’s in it.

These people live again in print as intensely as when their images were captured on old dry plates of sixty years ago… I am walking in their alleys, standing in their rooms and sheds and workshops, looking in and out of their windows. And they in turn seem to be aware of me. — Ansel Adams

Most of these old photos are presumed to be in the public domain by their age. I love the young woman in rowing costume with her perky porkpie hat.

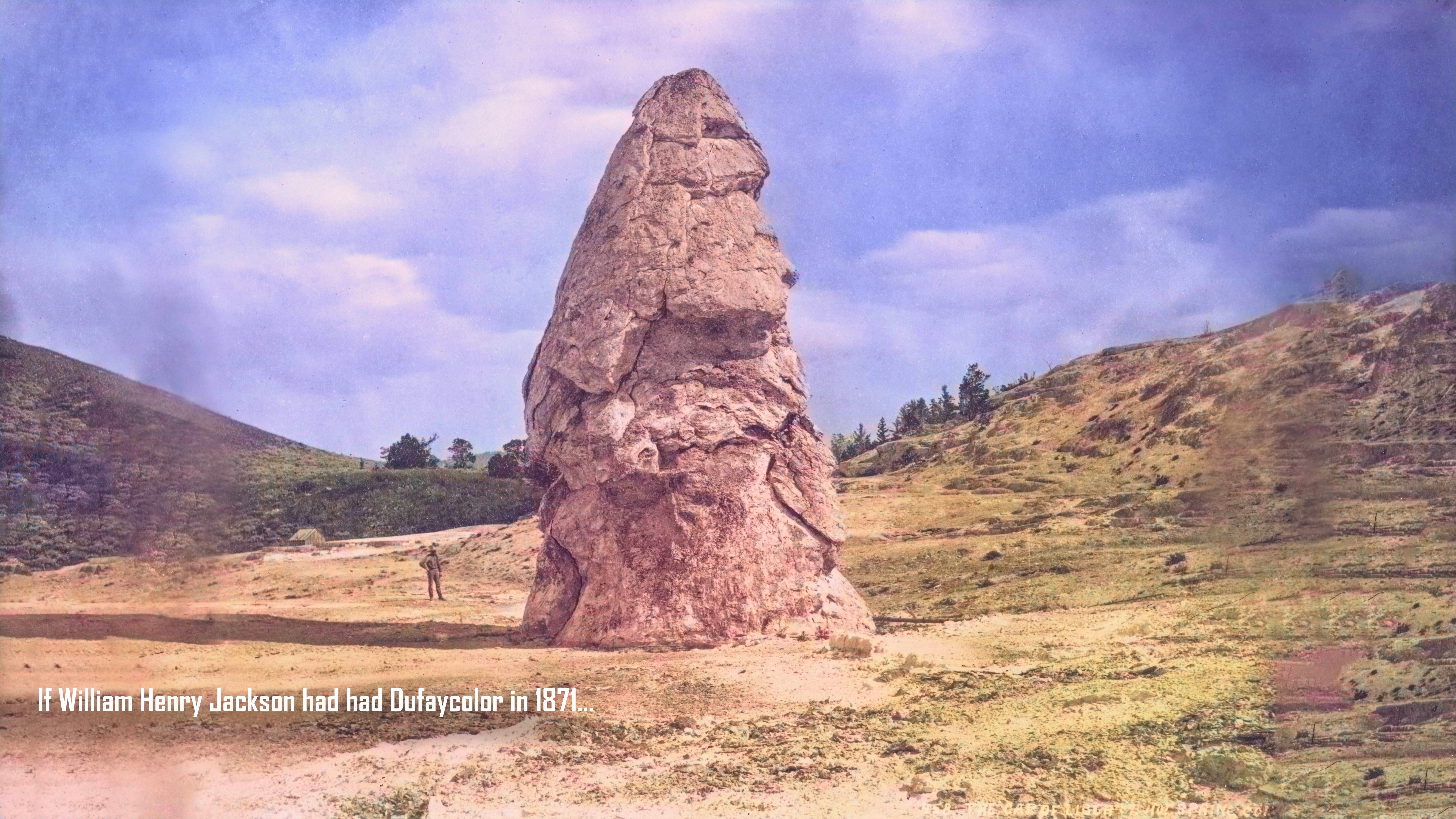

I have deep admiration for William Henry Jackson in the Yellowstone in 1870. State-of-the-art in his time was the incredibly cumbersome wet collodion process using glass plates. Ferdinand Hayden invited Jackson to join a government survey of the Yellowstone River and the Rocky Mountains as the expedition photographer. He went back in 1871 with the Hayden Geological Survey, which led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park. The excerpt below gives an idea of the challenges of photographing in the field in 1870–71.

WIKIPEDIA: Jackson worked in multiple camera and plate sizes, under conditions that were often incredibly difficult. His photography was based on the collodion process invented in 1848 and published in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer. Jackson traveled with as many as three camera-types — a stereographic camera (for stereoscope cards), a “whole-plate” or 8x10" plate-size camera, and one even larger, as large as 18x22". These cameras required fragile, heavy glass plates (photographic plates), which had to be coated, exposed, and developed onsite, before the wet-collodion emulsion dried. Without light metering equipment or sure emulsion speeds, exposure times required inspired guesswork, between five seconds and twenty minutes depending on light conditions.

Preparing, exposing, developing, fixing, washing then drying a single image could take the better part of an hour. Washing the plates in 160 °F hot spring water cut the drying time by more than half, while using water from snow melted and warmed in his hands slowed down the processing substantially. His photographic division of 5 to 7 men carried photographic equipment on the backs of mules and rifles on their shoulders. Jackson’s life experience (for example his military service, and his peaceful dealings with Indians) was welcomed. The weight of the glass plates and the portable darkroom limited the number of possible exposures on any one trip, and these images were taken in primitive, roadless, and physically challenging conditions. Once when the mule lost its footing, Jackson lost a month’s work, having to return to untracked Rocky Mountain landscapes to remake the pictures, one of which was his celebrated view of the Mount of the Holy Cross. [Emphasis added CGH]

Liberty Cap is a dormant, 37-foot high hot spring cone located in the northern portion of Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. — Waymarking. com

Wet collodion was state-of-the-art during and before the American civil war. One of the earliest photojournalists was Englishman Roger Fenton (1819–1869), who in 1854 was commissioned to photograph events during the Crimean War with Russia.

Fenton’s wet collodion emulsions were not very sensitive to light, so each picture required a long or longer exposure depending upon the light. He could only make pictures of stationary objects and posed images. He declined to make pictures of bodies, although that became common in the U.S. civil war seven years later.

The valley picture was not the location of the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade but several miles to the northwest, but there was no combat there at the time so that Fenton could set up and take his time. He made two exposures. One was just the rutted road, but cannonballs enhanced the other (above). Presumably, Fenton and his crew gathered cannonballs and placed them in the road for effect.

Photography in the vernacular is the meat and potatoes of nascent history. It’s only snapshots today, but their value increases with the distance of time. Treat your vernacular pictures with respect; back up your files. Digital photos are more fragile than you may think, easily lost, digital dust with the failure of a drive unless backed up on another drive plus (ideally) the cloud. Even better, print them. Above all, take them. Annie Leibovitz is another of my heroes…

Thanks as always for reading.