Dear George Orwell,

Why do we write? Given that words and reality, as you once put it, are so often « no liker » to each other « than chessmen to living beings ».

Because I’m writing to you now from a future no-one could have seen coming –– except maybe yourself, and H G Wells, and J G Ballard and the furthest-seeing writers over the centuries from Sophocles to Margaret Atwood.

Because everything you wrote gifts us with the knowledge that words are the chesspieces by which the powers that be will play their games with our lives. You know, as the current UK Prime Minister puts it, that « human beings are creatures of the imagination », that « people live by narrative ».

I’ve been reading your 1946 essay Why I Write, with its portrait of yourself as a child who already understood our natural attraction to narrative, our need of it to make sense of, mark and question who we think we are, and above all to let us be conscious of and about what it is we’re doing, both in reality and when we narrate ourselves via our fantasies of self and reality:

I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my « story » ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing … For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a matchbox, half open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window.

What a double-strength consciousness in you at this early stage, of how our versions of reality will involve not just a form of narration but also to some extent a crucial consciousness of that narration as construct. Look at the way that making a version of reality also involves a transformation into past tense. Why is that? Is the past tense more ceremonious? More handle-able?

« Who controls the past controls the future, and who controls the present controls the past. » This is one of your most famous examples of sloganeering, straight out of the totalitarian state, Oceania, in your great novel 1984. I was a latecomer to reading 1984, and when I found out that some of its original possible titles were The Last Man in Europe and The Last European I shook my head at the synchronicity, because I finally read it for the first time in 2016, in the initial shock of the EU referendum which, by proffering what looked like a future, shunted this country back into its past.

I was a much earlier reader of Animal Farm, 40 years earlier, in a class in Inverness High School in the Highlands of Scotland, where it was on the excellent school curriculum. I see now how it equipped me at the age of 14 with a way to register not just that power will corrupt but how it will. It also gave me an acute consciousness of the working of power in language.

Two legs bad.

Four legs good.

Such small words. Monosyllables. Such power when they’re put together.

Though some are more powerful than others, all slogans are powerful. The word slogan derives from Scottish Gaelic, from the words sluagh and ghairm, meaning war and cry. At root, a slogan’s a war cry, whether it’s take back control, make America great again, kauf nicht beim Juden, it’s the real thing, I’m lovin’ it, just do it.

Because of you we all know how to read with our eyes open. Take the contemporary terms woke or virtue signalling, their reduction, dismissal and patrolling of people’s ethical attentiveness easily unmasked as one of the oldest tricks in the book, as blatant persuasion to get people to press the sleep button not just on activism but on any articulation of ethical consciousness. Or the word antifa, an edited-down version of the word antifascist, coined specifically to cloak then remove the verbal presence, the threat, and the real history of the word fascist, and replace it with a coining that changes the act of opposing fascism into something made to sound a bit foreign, a word not from round here.

« A sleepwalking people ... the phrase that Hitler coined for the Germans », you wrote. Doublethink is the word you yourself coined in 1984. At its heart, you said in the novel, doublethink performs « the ultimate subtlety: consciously to induce unconsciousness ».

All narrative is hypnotic. Some narratives are more hypnotic than others. Because of you, we can be conscious of the kinds and the workings of the narratives that set out to deaden us, lessen us, make us lie, make us part of the lie.

II

So here we are in all the consciousness, subconsciousness and unconsciousness of the 2020s. In a time when we’ve globally been united by having to consider like never before what it means to be able to breathe freely, I’ve just read, for the first time, your 1939 novel Coming Up for Air. You wrote it in Morocco where you went in 1938 to try to scotch the start of what would later be diagnosed as TB, the disease that would get you in the end. You’d also not long before been wounded by a bullet in the throat in the Spanish Civil War, where you encountered « human beings ... trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine » at the same time as you encountered the bitter lying, the fake news, the internal treachery, that happens no matter what side you’re on when power and politics make real mincemeat of real people then lie about it afterwards.

Your subject, I think, all through your oeuvre, is the urgency of unmasking both truth and lies, and narrative’s role in these, and the question of the life it’s possible to live between truth, lies and fiction in a world where « yesterday’s weather can be changed by decree », when the fragile balance that lets us live lives without being reduced to bloody mincemeat starts to tremble. On the one hand, the knowledge that « however much you deny the truth, the truth goes on existing. » On the other –– and we’re all deep in this seductive divisive quagmire right now nationally and internationally all over again –– how « everyone believes in the atrocities of the enemy and disbelieves in those of his own side, » how « the truth becomes untruth when your enemies utter it. »

Coming Up for Air is a funny, mordant piece of English disabuse, a novel about the big and little truths and lies in the average life of a man with an average wife and two kids, « Tubby », or George Bowling, 45, who loves his family in that qualified English way, and is rising in the insurance trade, but not very far, probably not much further. He’s had a not very idyllic childhood in a place not very hopefully called Lower Binfield. By chance he’s read a few books, nothing too grand or intellectual, but he likes how they make you think. He loves fishing, but hasn’t been fishing for years. He’s put on enough weight to feel the eye of social judgement on him. But he understands that. He’s a modern chap in a time where, « if you see a man down », the thing to do is « jump on his guts before he gets up again. » George bowls along like the novel itself does, with heady lightness tethered to a claustrophobic undertow, one world war behind him and another round the corner. Doomed, cheeky, like the novel’s epigraph straight from a funny Gracie Fields song, he’s dead but he won’t lie down. What can bring him truly alive? Going back to the past, maybe? « Sometimes when you come out of a train of thought you feel as if you were coming up from deep water, but this time it was the other way about, it was as though it was back in 1900 that I’d been breathing real air », he thinks, before the novel makes clear the lie at the heart of any return to a perfect past, because this is a novel about irrevocable change, and about facing that change. That pond where you first fell in love? It’s now a rubbish dump. The big house everyone aspired to? Now a lunatic asylum. George looks around him at the learned, at the blindly loyal politicos he encounters, and at himself, and thinks « perhaps a lot of the people you see walking about are dead. ... Perhaps a man really dies when his brain stops, when he loses the power to take in a new idea. »

The book’s most cold-eyed moments, when the truth of a life cuts through the self-serving myth of that life: these are what let George and the readers of this book catch their breath, get their breath back, remember the difference between the inspire and expire of breathing –– in other words between living and dying. How not just to stay alive, but truly to be alive, to the changes, through the changes. The novel brings its England up from its deeps to the surface and says, go on, take a breather, but it never compromises on the dark of the undertow. Insurance? against totalitarianism? when « the world we’re going down into », as George says, is « the kind of hate-world, slogan-world. The coloured shirts, the barbed wire, the rubber truncheons. The secret cells where the electric light burns night and day, and the detectives watching you while you sleep … »

How outlandish fiction is! Not here. That’ll never happen here. Well. Let’s take just one of those images: those night and day burning electric light cells. They’re how the UK government, right now, houses the most mentally traumatised of its detained refugees in the private security-company-run detention centres up and down England. Solitary, 24 hour lock-in, checks every few hours through the door-hole, in a country whose government is determined, as I write, to legislate to criminalise refugees along with other « outsiders » like travellers and protesters. That’ll sound very like something you watched happen not that far from home in your own lifetime, Mr Orwell, something against which you judged it worth fighting a world war.

« And what’ll happen », here’s George Bowling’s voice nearly a century ago, « to chaps like me when we get fascism in England? The truth is it probably won’t make the slightest difference. ... It’s all going to happen. ... it was as though the power of prophecy had been given me. ... I could see the whole of England, and all the people in it, and all the things that’ll happen to all of them. »

Of course I expected prophecy. What I didn’t expect was to find quite such piercingly personal shades of my own life experience. In Coming Up for Air, George Bowling’s parents are small shopkeepers. They run a meal supply business and a store. It looks like it’ll last forever. Then a conglomerate opens in Lower Binfield and kills off George Bowling’s father’s shop and business. My own father was one of the few electricians in Inverness when we were growing up; he had 30 men working for him and a shop that mended goods and sold lightbulbs, batteries, toasters, hairdryers. When Dixons and Currys and Thatcherism happened it did his business in. Why mend a toaster when you can buy a new one so cheap?

Or no, okay, it’s just time, and change, that did his shop, his business, his life, in. Time’ll do us all in. As to change, I wonder what you’d reckon to the England I’m writing from right now, with its spanking new Westminster media centre union jacks, and with the constituent parts of the nominal unitedness of the kingdom now pulling away from England in all directions. Scotland will leave; brexit has reignited its european roots. And Ireland will reunite. And Wales has seen the potential too for another future. This is real change, and it’s been brought to surface by the actions of the same-old same oldness that you write about in The Lion and Unicorn in 1940: « Right through our national life we have got to fight against privilege, against the notion that a half witted public schoolboy is better for command than an intelligent mechanic. »

I think our current version of this public schoolboy has all his wits about him and is one of the best fictionalists I’ve ever seen in politics, and always in service to the lie. Well, as you say, « such leaders only appear when the psychological need for them exists. » But much bigger than this, and them, is real ancient change, change by plague and pestilence, and a whole new ordeal by fire and flood, climate change, which’ll teach us all the truth: that borders are random, that the planet is way bigger than the lies the conglomerates and self-serving leaders have been selling us.

So. Why write anything?

Here are two past tense moments from my own life that’ve let me come up for the kind of air that means we know the imperative to envisage a better future.

The first comes from a visit I made myself to Morocco twenty years ago when I spent a week with Medicin sans Frontiers in Tangiers, meeting refugees from sub-Saharan Africa who were trying to get to Europe. My guide and interpreter was a man who asked me to call him Pascal; he didn’t want anyone to know his real name. He was on the run from people who wanted him dead because they thought he was the wrong religion. He could speak more languages than most people I’ve met; he had the top segment of a finger missing, and an earlobe gone too, and when I asked him what had happened to him he told me he lost both to the netting of an underwater barbed wire fence he’d been trapped in and had had to tear himself free of so as not to drown.

The other moment is to do with my father’s life; it’s something I’ve written about before, elsewhere, but think it makes sense here to tell it again. It relates to your own vision, Mr Orwell, of how this country and its countries would come up for air after the Second World War –– when « the working class », as you put it, would, « want some kind of proof that a better life is ahead for themselves and their children. » Your vision was of a benign revolution. The welfare state, it turns out, was revolutionary. It wildly brightened people’s life chances. My family’s for sure. But my father’s take on this betterment was less about us all being given an equal chance and more about levelling up, to use a hollow slogan from our own times. He went from poverty into the navy, enlisted in 1942 as soon as he was 18 because the navy paid more than the brick factory. And the navy taught him a trade for life, and the war gave him nightmares for life. To assuage these nightmares he’d often proclaim to us, his kids, we fought that war so that the sons of common men like me would be admitted to the playing fields of Eton. Not the daughters, note. My dad was of his times too. We all helplessly are.

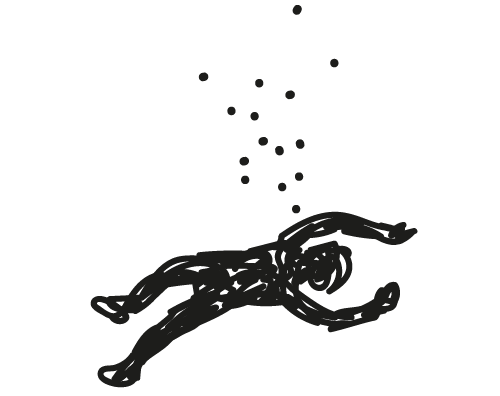

Anyway, at the time in the war when the Italians switched sides, and the ship my father was serving on was sailing up to Italy, one day he was leaning over the side miles from land when he saw a horde of paratroopers, allies, Americans, and they were all hitting the water because they’d been dropped too far out at sea. Hundreds of them waving up at the men on the ship. There’s no way a ship can stop, my father said when he told us this story half a century later. So they called down to the men in the water that they’d come back for them, they’d pick them up on the way back. Of course, the men on the boat knew they wouldn’t, and the men in the water knew they wouldn’t too.

Some waved down. Some waved up.

The ship sailed on.

Why we write.

Much love, dear George Orwell, from this writer, this lifelong grateful reader.