Today we take them for granted, but in the 1960s interracial duets were almost unheard of. Diane Bernard explores the forgotten story of Storybook Children, the taboo-busting song that became a hit.

I

In May of 1968, just a few weeks after Martin Luther King Jr's assassination, singing duo Billy Vera and Judy Clay entered the Apollo Theater in Harlem, then an all-black neighbourhood of New York. Vera had teamed up with gospel-and-soul diva Clay to sing their new hit love song, Storybook Children. When Apollo announcer Honi Coles saw the couple, he said to Billy Vera, "The Apollo hasn't seen you before," Vera tells BBC Culture.

More like this:

- Who was the real Elvis Presley?

- Inside Kate Bush's alternate world

- The music embedded in our psyches

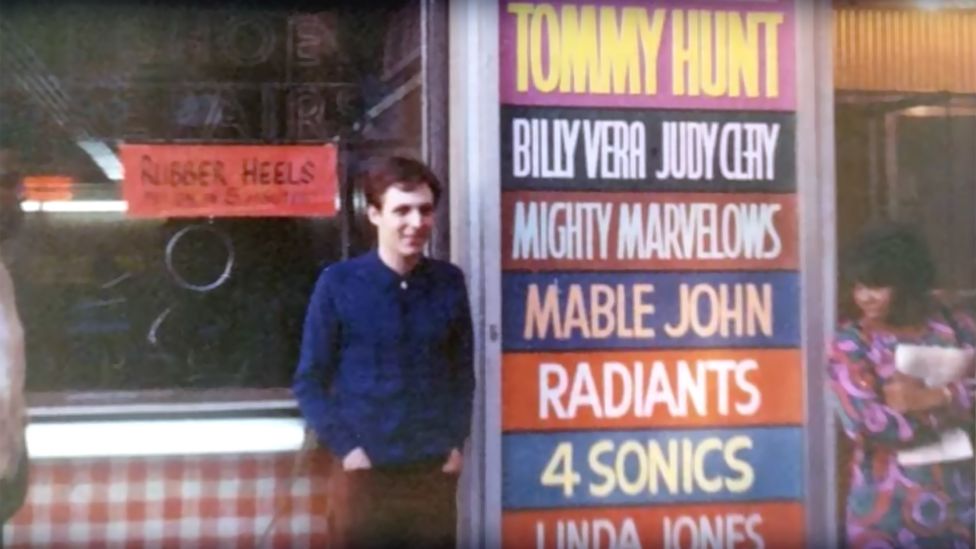

Ever the showman, Coles told the couple to stand on opposite ends of the Apollo's storied stage. Judy came out first on the right, her floor-length cream-coloured gown shimmering under a spotlight. Then, the left spotlight shone on Vera as he stepped forward in an olive-green mohair suit and tie. When the audience saw the young white man, the entire auditorium gasped in shock. "That's him? That skinny little white boy?" Vera overheard someone in the crowd say. A major hit in the New York area, no one knew the male lead on Storybook Children was white. The couple burst into the song, serenading each other with powerful harmonies, building a gritty, emotional surge of heartrending longing: "Why can't we be/ Like Storybook Children/ Runnin' through the rain/ Hand in hand/ Across the meadow?"

The duo caused a stir when they performed together at Harlem's Apollo Theater (Credit: Billy Vera)

"On stage they were electric," says blues singer Mabel John, who was on the same bill at the Apollo that week, and saw the duo's live performances: "This being the first black woman and white guy teaming up together and singing at the Apollo – and they're not just making noise, they are making music. And the people stood to their feet."

With rioting surrounding Martin Luther King Jr's assassination still raging across the Hudson River in Newark, New Jersey, music history was being made in Harlem. America's first interracial singing duo to hit the Billboard charts was singing live for the very first time, playing five shows a day for seven days.

"It was groundbreaking," says Vera, who became an R&B historian, winning a Grammy for writing liner notes to a Ray Charles CD box set. "America was just on the verge of being ready for an interracial duo singing love songs – but they weren't quite there yet."

But for that night, and many others that week, Vera and Clay could hardly get off the stage, there were so many calls for encores, John says.

After one of those sets, "we finally came offstage and I saw [gospel great] Cissy Houston, Judy's adoptive aunt, with tears running down her cheeks, holding four-year-old Whitney," Vera says. They were so proud.

Vera and Clay released their single and album just three months after the 1967 US Supreme Court case Loving v Virginia, which legalised interracial marriage. Yet, few know of their accomplishment. Loving Day, an international holiday celebrating interracial love, which marks that case, was earlier this month, also coinciding with African American Music Month in the US, and Vera and Clay's album represents a pioneering development in America's social and musical history.

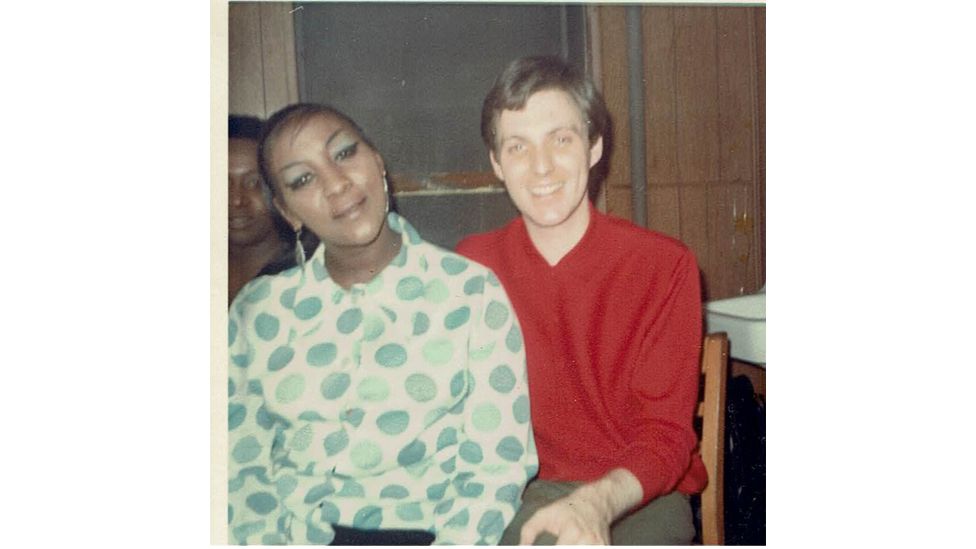

The duo – snapped here backstage – were the first interracial pair to record a love song in the US (Credit: Billy Vera)

Today, musical duos of different ethnicities are a usual part of the pop cultural landscape, but in the autumn of 1967, when the duo's album, also called Storybook Children, was released, it was a shock to see a white man and a black woman on an album cover, and singing a love song. Vera wrote the single, Storybook Children with songwriting legend Chip Taylor, who penned Angel of the Morning, Wild Thing and I Can't Let Go by The Hollies, among other hits. Taylor says the song was first inspired by seeing two children, a white boy and a black girl, holding hands walking through an open field in an area outside New York City. "It was a time when that wasn't so acceptable and it was such a nice feeling, like a storybook," he tells BBC Culture. He says he couldn't wait to get into the city to write about them.

Vera says after they finished writing the song, it actually became a song about adultery, although it was first inspired by a glimpse at the potential for race relations to heal. At the time, Taylor and Vera didn't necessarily seek out a black singer for the duet. They tried out several women, black and white, but no one blended well with Vera's voice. Then Vera turned to Atlantic Records producer, Jerry Wexler, who was in Memphis working with Aretha Franklin at the time, for advice. Wexler recommended a gospel soul powerhouse, Judy Clay, who was signed to Atlantic, but hadn't had much success on her own. In an audition, Clay's dynamic singing and Vera's smooth soul sound blended together perfectly. They recorded the song Storybook Children, and the album by the same name, in September 1967.

With widespread radio airplay in New York City and surrounding East Coast areas, Storybook Children shot up the charts, and reached number 20 on the US R&B charts and 54 on the pop charts. It also reached number one on black stations in the city and number three on white stations, Vera says. "Our audience was mainly middle-class black people and working-class white people," he adds.

The duo was clearly in the vanguard. In 1967, when miscegenation laws were overturned in the US, just 3% of all newlyweds in the country were married to someone of a different race or ethnicity, according to the Pew Research Center. Since then, intermarriage rates in the US have climbed, the centre reports, and by 2015 they stood at 17%. "[Storybook Children] was radical," says Gayle Wald, historian and author of the 2006 biography, Shout, Sister, Shout!: The Untold Story of Rock-and-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe. "It represented a hopeful narrative of some kind of attenuation of racism: it was a material enactment of King's hope for a beloved community."

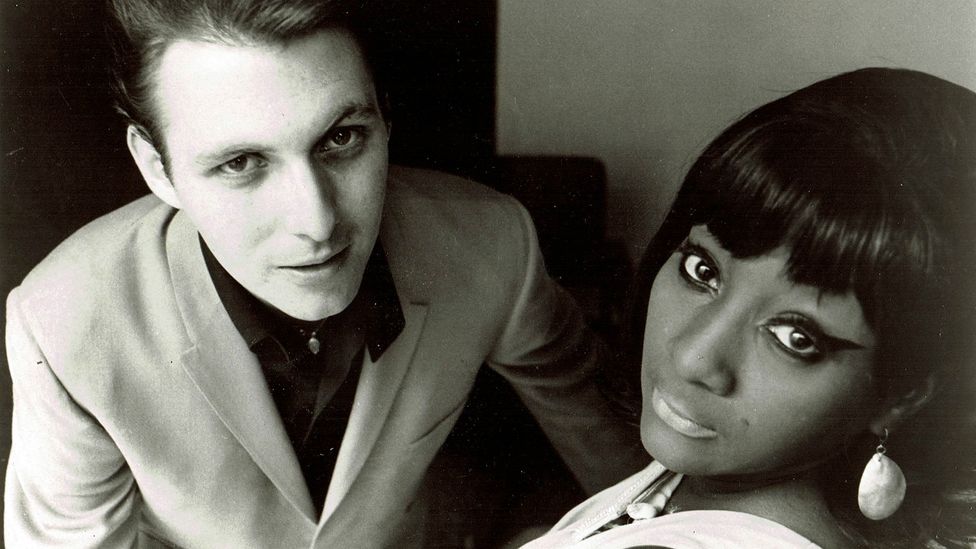

Groundbreaking duo Judy Clay and Billy Vera had a hit with their love song Storybook Children in 1967 (Credit: Billy Vera)

But Vera says the pair's influence was muted at the time. Music and television executives warned him the duo wouldn't get much TV airtime because Southern stations might lose sponsors if they showed a white man singing with a black woman on local television, especially a love song. The pair did however appear on one TV show in Detroit and a live show in Pittsburgh in the autumn of 1967 and winter of 1968 – as the song continued to rise on the charts. "We also taped a TV show in New York with disc jockey Clay Cole, but they never aired our segment," Vera says. Some have said it was because we were an interracial couple, but we'll never know for sure, he adds.

Another impediment to their rise in pop stardom was that Judy Clay became pregnant at the time of the song's release, and so wasn't able to tour. Seeing the album cover, a close-up of a white man in a brown mohair suit standing behind an attractive black woman in a blue gown and large hoop earrings, cocking her head to one side, must have come as a surprise to the record-buying public. Yet, famed Colony Records on Broadway and 51st Street featured an entire window of the album cover, Vera says.

Crossing boundaries

Vera and Clay weren't the very first interracial duo to release a song together, however. In 1952, R&B guitarist and singer Sister Rosetta Tharpe teamed up with white country artist Red Foley to record the Christian-themed Have a Little Talk with Jesus on Decca Records, according to Wald's book. The song was released as a B-side and didn't get much public attention. However, "the Tharpe/Foley duet was profound," Wald tells BBC Culture. "It shook up everything by crossing boundaries that had not been crossed before," she adds, especially in light of the US's miscegenation laws against interracial relationships. In many Southern states, what Tharpe and Foley did was so taboo it might have been considered illegal by some.

Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald had sung duets together, especially on Sinatra's TV shows in later the 1950s. But no interracial duo had recorded a record before Tharpe and Foley, Wald's research shows. "It just runs against so many of the social and musical conventions of the time," US music historian Peter Guralnick tells BBC Culture."Storybook Children and Just a Little Talk with Jesus help to surface histories of cross-racial connections that are not necessarily part of official histories," says Wald. "They help us understand American social and cultural life more fully."

The legendary Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York, pictured in 1967 (Credit: Billy Vera)

After Storybook Children in 1967, the music industry began seeing more and more interracial duo releases. "This was a time when pop music was starting to integrate more, with bands like Sly and the Family Stone, Wild Cherry and the Ohio Players just getting their start," Vera points out. "But there's a difference between a big group integration and a couple singing a love song – there were all these taboos around interracial sex."

In 1976, mixed-race couple Leon and Mary Russell released The Wedding Album, and later that year the couple performed the single Satisfy You on national TV show Saturday Night Live, showing wider acceptance of integrated singers both in the music business and the culture at large.

After Rick James's hits with white soul singer Teena Marie in the 1980s, many more interracial duos recorded hits, from Al Green and Annie Lennox's 1988 Put a Little Love in Your Heart to 1998's If I Told You That by Whitney Houston and George Michael, with Houston following a trail blazed by her adoptive cousin, Clay.

Unfortunately, Storybook Children did not experience the widespread success of these later recordings. Part of that was timing: "The culture was shifting more towards hippy influences and we were sort of old-school soul, even then," Vera says. "We weren't wearing long hair and bell bottoms – we dressed like old rhythm and blues artists."

Then, a distribution deal between Atlantic and Stax records that allowed Clay and Vera to record together ended, and the labels chose not to renew the relationship. "So Judy and I were no longer contractually allowed to sing or record together," Vera says. The next year, Clay was released from her Stax contract for the pair to record the country-tinged soul song Country Girl, City Man, which became another hit for the duo. When the Apollo asked the pair to return after the success of Country Girl, City Man, Clay refused, demanding more money. They never returned to the Apollo stage. Vera says Clay had developed a resentment grown out of frustration. Originally from gospel royalty, Clay grew up in North Carolina and in the late 1950s at just 14 years old, she moved up north to Newark, New Jersey. There, she joined New Hope Baptist Church, where music giant Dionne Warwick's mother, Lee Drinkard had formed her seminal gospel group the Drinkard Singers.

"Being without parental guidance and on her own, my mother took her in to stay with our family," Warwick, who's currently on tour in the UK, tells BBC Culture. "She was an integral part of the Drinkard Singers." Her vocal talent was "incredible", according to Warwick, "and she was a fun person with a wonderful personality."

Duo Billy Vera and Judy Clay pictured outside the Apollo in 1967 (Credit: Billy Vera)

After leaving the Drinkard Singers in the early 1960s, Clay recorded a few songs for Scepter Records, but they didn't chart. Meanwhile, the career of her adoptive sister, Dionne, was taking off. And other Drinkard Singers, including Cissy Houston, Dionne's aunt and Whitney Houston's mother, formed the Sweet Inspirations, singing backup on many Atlantic Records hits including the Storybook Children album. With her towering vocals, Clay wanted to be a star, too, Vera says. After Country Girl, City Man, Clay continued to sing back-up vocals for soul legends including Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Van Morrison and Aretha Franklin. She scored a hit with William Bell in 1970 with Private Number, which reached number eight in the UK singles charts, and did well in the US. But she never had the successful solo career she yearned for.

"Her contribution to the recording world with [Storybook Children] and her performances should be recognised as something that was truly meaningful," Warwick says.

In 1979 after surgery for a brain tumor, Clay returned to her gospel roots. Then in 2001, she died in a car accident at age 62, never receiving the acclaim she deserved.

More than 20 years after Storybook Children was released, in the 1980s, Billy Vera was producing albums for the Grammy award-winning soul singer, Lou Rawls. Rawls invited Vera along to an Apollo Theater event, and there they ran into legendary Harlem showman Ralph Cooper, who'd been affiliated with the Apollo since the 1930s.

"He saw me and threw his arms around me," Vera says. "He told me, 'your picture's in the lobby and will always be there.'

"What you did was so important," he said. "Welcome home."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.