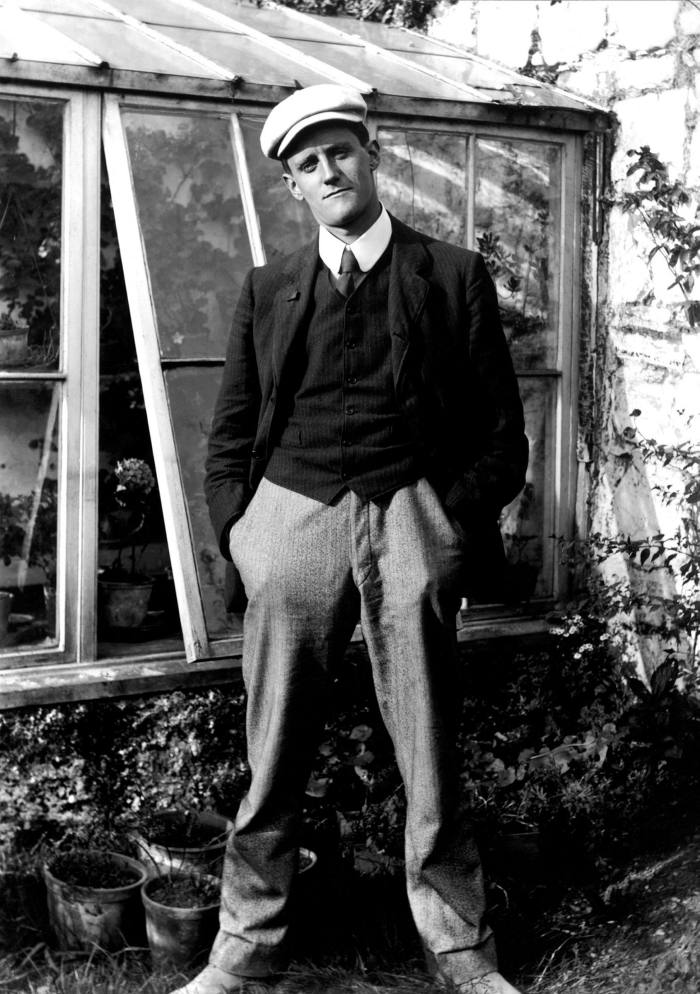

Millions of litres of turbulent Atlantic water are funnelled into a narrow briny bottleneck between Ireland and Britain, making the 100-odd km stretch of the Irish Sea between Dublin and north Wales a lot choppier than you’d think. Sailing horizontally east to west across vertical Atlantic winds is no joke. Yet on an unseasonably warm October night, a lanky 27-year-old in tennis shoes does just that. He staggers along the galley of the Holyhead to Dún Laoghaire mail boat, and pukes violently overboard.

James Joyce is coming home. But why?

A month earlier in September 1909, Joyce’s sister, Eva, was enjoying the cinemas in Trieste where Joyce had exiled himself. By 1909, there were 21 cinemas in Trieste. Eva mentioned she thought it odd that Trieste had so many cinemas yet there wasn’t one in Dublin, a far bigger city. Joyce, himself a cinema buff, saw his opportunity: he’d open the first cinema in Ireland and make his fortune. But he had no money; he must find backers. Luckily for our young entrepreneur, Trieste, cosmopolitan and commercial, was an ideal spot to raise money. Joyce quickly found a syndicate of potential financiers.

At the critical elevator pitch, Joyce whetted investors’ appetites with the opening gambit: Dublin, a European city of 350,000, had no cinema and two more cities in the same country, Cork and Belfast, were also without a cinema. (Joyce the hustler bumped up Dublin’s population to 500,000 for effect.) Ireland, with close to a million urban dwellers, was virgin trading soil ripe for far-sighted operators. For a man who was a better spender than saver who would experience money problems throughout his life, the contract Joyce negotiated reveals a canny financial operator, and a true salesman. He convinced the partners to give him 10 per cent of the equity and profits, although he didn’t invest a penny. He was also paid expenses and a wage. Hands were shaken, the deal was done, Joyce was off. The portrait of the artist as a young entrepreneur.

Why do we still find it so hard to accept that these two roles — the artist and the entrepreneur — are not mutually exclusive? A century after Joyce’s Ulysses introduced the world to a new sort of novel, the lazy idea of the indigent creative set against the uninspired commercial, the ingenious bohemian versus tedious bourgeois, remains as powerful as ever. Yet as Joyce’s cinema venture showed, the mind that wrote Ulysses was also the mind that opened Ireland’s first cinema.

With a material upside if things worked out, Joyce went about his business with uncharacteristic freneticism, negotiating property with landlords, discussing colours with painters and decorators, selecting films with distributors, talking to newspaper admen about publicity, buttering up journalists for flattering reviews, becoming expert in many fields from seating and upholstery to lights, technical projector operation, and pricing structures for his various shows (cheaper for matinees, more expensive for the evening headliner). Joyce, the perennial bankrupt, proved to be a dab hand at cash flow management. In terms of publicity, something he took to naturally, Joyce generated enough hype to ram the opening night, making the grand opening on December 20 1909 a must-see event.

Any new venture in Dublin can count on half the city cheerleading your impending failure, particularly if you’re a returned local, made-good, showing up the inactivity of the left-behinds. How many peers must have spat into their pints when they read the Evening Telegraph’s review of the Volta?

Remarkably good . . .

Admirably equipped . . .

Large numbers of guests . . .

No expense spared . . .

Particularly successful . . .

Excellent string orchestra . . .

Mr Joyce has worked apparently indefatigably and deserves to be congratulated on the success . . .

In January 1910, having acquired the finance and successfully established the brand, Joyce headed back to Italy, leaving a manager from Trieste to run the show in Ireland. (Without the entrepreneurial Joyce in Dublin, the cinema faltered, the shareholders squabbled and the hired management ran an initially successful business into the ground.)

The artist as entrepreneur

It should not surprise us that Joyce the artist was also Joyce the entrepreneur. Artists and entrepreneurs are blessed with similar convictions. Both are innovators. They see possibilities where others see limitations, bringing the previously unimagined into being. Both have skin in the game, living in the theatre of risk, performing on the public stage of jeopardy. Failure can be brutal and success is often a prelude to future disappointment but they are driven ever-forward by self-expression; it’s in the DNA of these independent, slightly unreasonable, regularly difficult people. Cussed mindsets have no alternative. Both the artist and the entrepreneur suffocate when shackled by a boss, a wage or an insurance premium.

Born disrupters, truly great artists and entrepreneurs are modernists, creating demand where none previously existed, conjuring something out of their imagination and courage. Unlike the critic, the artist and entrepreneur are eternally optimistic. They must believe in the future. The optimism of their will overcomes the pessimism of their intellect. Originality is their currency and constant adaptation their tool. The artist and the entrepreneur, so often pitted against each other, are in fact on the same side. Historically, societies that welcome these dissenters are rewarded with the most dynamic economies. Healthy economies, like healthy artistic cultures, thrive on dissent and diversity. As the 20th-century economist Joseph Schumpeter noted, the essential fact of any economy is innovation, or what he termed the “gale of creative destruction”.

Any country open to independent thought, that venerates diversity, is also likely to generate innovative energy. Societies that dignify outsiders prosper economically and artistically, as courageous types express themselves creatively and commercially. These are the traits of a liberal society: open, non-judgmental, preferring rationality over superstition, science over falsehood, proof over conjecture, reason over religion, and questioning over dogma. This is what Joyce saw all around him when writing Ulysses in multi-ethnic, mercantile, tumultuous Trieste, a thriving, bustling city in the centre of Europe, yet on the edge of everything. Dublin was not such a place. Leopold Bloom, the anti-Homeric hero with whom we spend the novel’s single day, may have been at home in Joyce’s Trieste but by placing him in Dublin, Joyce invented the ultimate Irish outsider.

Today, where does the creative cosmopolitan of Joyce’s imagination, Bloom — a Jew by his father’s name, yet baptised three times, once Protestant, once Catholic and once for the craic — feel at home? In 2022, the country or city that provides refuge for these commercial, social and creative dissidents will be rewarded both culturally and financially. Art and commerce go together.

Bloomonomics

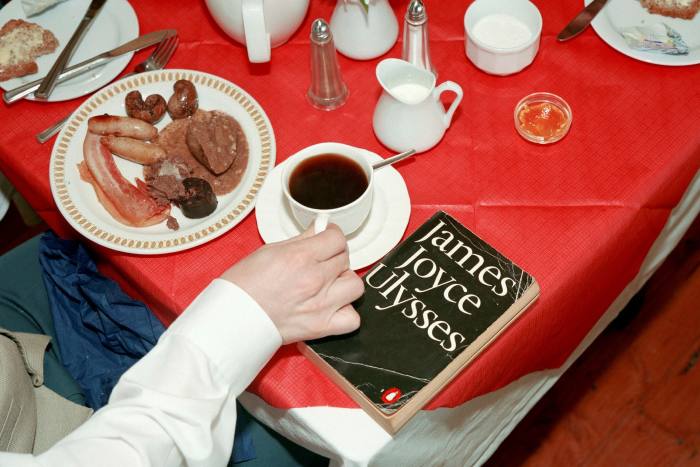

In Dublin, to celebrate Bloom’s love of offal, Bloomsday breakfasts on June 16 have become an exuberant embarrassment of innards, suitable only for those of a certain constitution. This coming Thursday, the city will be awash with dressed up Joyceans chomping down all classes of offcuts. One hundred years on, his dietary delectations are well-appreciated, but Bloom’s sophisticated economic mind is sometimes forgotten. In “Calypso”, the fourth episode of Ulysses, Bloom’s opening concerns rest squarely in the realm of the economy. With a combination of engineering exactitude softened by a profound understanding of human emotions, Bloom displays the foundational elements for what John Maynard Keynes, Joyce’s contemporary, suggested is the basic chemistry of the master-economist:

[T]he master-economist must possess a rare combination of gifts. He must be mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher — in some degree. He must understand symbols and speak in words. He must contemplate the particular, in terms of the general, and touch abstract and concrete in the same flight of thought. He must study the present in the light of the past for the purposes of the future. No part of man’s nature or his institutions must lie entirely outside his regard. He must be purposeful and disinterested in a simultaneous mood, as aloof and incorruptible as an artist, yet sometimes as near to earth as a politician.

Crucially as befits a constantly curious mind, Bloom was non-ideological. In time, we will see him support some contemporary economic ideas identified with both the left and the right, such as the universal basic income, public investment in utilities, municipal reform and annuities to minimise inequality at birth. He values hard work and innovation, displaying an acute dislike for casino capitalism with its speculation or easy gains. Living off his wits, Bloom earns his crust as an advertising copywriter, and with that detail, Joyce immediately makes Bloom the scourge of all Marxists and assorted materialist dialecticians. Preferring reason to rules, he doesn’t fit neatly into any ideological box.

In the opening pages of “Calypso”, we see a fertile economic imagination at work. Once outside his Eccles Street home, at 8am on June 16 1904, Bloom’s first calculation is a purely commercial one. Can he flog an ad? The sun is rising, he’s daydreaming of Arabic markets, stale turnover bread, his father-in-law’s moustache and Molly’s scarlet garters. Bloom sizes up the moneymaking potential of corner publican Larry O’Rourke.

The next thought has Bloom contemplating an imagined map of the city that allows a walk across Dublin without meeting a pub. Surveying the street down from O’Rourke’s bar, he muses in the same breath that if the council were to run a tramline up the road, “value would go up like a shot”. In one half-thought, Bloom captures the essence of the argument outlined in the popular economics book written just before Joyce’s birth: Henry George’s Progress and Poverty. With admirers as diverse as Shaw and Tolstoy, this book was a bestseller in America. Central to George’s work was the notion that public investment, such as a tram for example, enriches private owners rather than the general citizenry, and this is precisely what concerned Bloom.

The issue — considered by Bloom — comes down to who finances public investment and who should benefit: the taxpayer or the property speculator? Speculation and this type of “easy money” didn’t sit well with the creative and workmanlike instincts of Bloom. (Of course, his antipathy to the gambler may also have been influenced by his nemesis, Blazes Boylan, who was fond of a flutter on the horses.)

Moments later on Dorset Street, he observes the notices in the Zionist newspaper in which his morning kidney has been wrapped by the Jewish, but non-kosher, butcher Dlugacz. The ad promises orange groves and almond trees. The non-Zionist Bloom sees it as a property shakedown, dressed up as the promised land, the commercial equivalent of turning water into wine. As an advertising copywriter, Bloom understands economic value resides in the brain; highly subjective, open to persuasion and ever-changing. Like Joyce, Bloom would have been very much at home in the future; Bloom’s advertising mind was perfectly suited to the Instagram age, rooted in the power of suggestibility and emotion.

Having assessed O’Rourke’s commercial worth, noted the anti-democratic way public wealth accrues to private property owners, Bloom then (on the same page) muses on the profitability of dreams captured in the Zionist paper’s ad selling an imagined new life in what (spoiler alert) will become Israel. We are talking 1904 not 1948 here. This is not the mind of some ideologue but the mind of the marketeer, who spies opportunities.

Politically, Bloom holds fast to liberalism, occupying the tolerant centre where the outsider feels most comfortable or maybe least uncomfortable. Bloom celebrates diversity — on the street, in the bar, at the funeral, down in nighttown, in the cab man’s shelter, the shops and parks. As he strolls Dublin’s streets, he bumps into rich and poor, Dubs and culchies, young and old, spoofers and savants, nationalists and unionists, whores and coppers, Christians and dissenters, artists and entrepreneurs, bohemians and bourgeoisie. The city is neither one thing nor the other, but a fusion.

Bloom’s Dublin was a diverse ecosystem, fragile and strong at the same time, interdependent and complex, but ultimately alive and diverse. Diversity loves freedom, and Bloom, the outsider, revelled in it, musing on Dublin’s sanitation, water pressure, tram timetables, canals, housing, electricity, rates, politics, sex, music and everything in between. Bloom extols diversity in residential and commercial buildings, diversity in transport, racial and social diversity, diversity in the public and private economy, diversity in architecture, and the dream of a future-orientated city, embracing science, progress and difference, turning its back on fundamentalism, nostalgia, mythology, sexual strictures, opening itself up to the adventure of the day and, of course, the night which all proper cities promise. Above all, the city is somewhere where synthesis can occur, common ground can be found, facilitating the great revolution of economic innovation.

The bohemian bourgeois

At its heart, Ulysses is about the unlikely friendship between the bohemian young artist Stephen and an older, wiser, bourgeois Bloom. The novelist son with the adman father; the poetry with the prose. At around 4am, as the book moves towards its conclusion, a sober Bloom takes brothel-weary Stephen to the cabman’s shelter. It’s time to get serious. Fatherly Bloom seeks to help the younger man navigate the obvious pitfalls of Dublin, both the source of creativity and (as my own mother warned me) the graveyard of ambition. Exhausted, the pair head to the sanctity of the cabman’s hut under Butt Bridge. Like Bloom, Joyce knew that Dublin was full of the “what might have been”, the great talents unrecognised, dragged down by the immaturity of the artist waiting for something to happen. This is Stephen’s Eminem “Lose Yourself” moment. And Bloom knows it. Bloom, ever pragmatic, insists that theory and practice, brain and brawn must be reconciled; the bohemian can only reach his full potential by succumbing to the discipline of the bourgeois.

Picture the lanky Joyce of October 1909 puking on the Dublin mail boat: the moment the artist and the entrepreneur merge, combining the best of both impulses. The brothels and the carousing pubs of Dublin are faux bohemia, swamps of bitter mediocrity, places that will sap Stephen of his genius. It’s time to sober up and knuckle down. This is something Joyce himself understood when he opened the Volta. The creative business mind and the creative artistic mind are one and the same type of machine: iconoclastic, irreverent, innovative but ultimately liberated by work, hard work.

Bloom, like Joyce himself, is juggling the bohemian and the bourgeois. Joyce wanted the family life, but also the excitement. Bloom wanted the stable marriage — which he couldn’t achieve — and the bohemian street life. Both realise that bohemian brilliance can only be fashioned by bourgeois discipline, artistic vision with entrepreneurial execution. Joyce, through the older more experienced Bloom, is trying to lead Stephen towards the sunlit uplands of application and grit. This is the moment of commercial fusion: when inspiration meets perspiration, when innovation and human ingenuity fuse with mercantile determination. In a Schumpeterian gale of creative destruction, the old is destroyed and something new is created. Modernism incarnate. Great art, great literature and great economies are designed, fashioned and completed in the same way, on the same road; and Leopold Bloom knew all the signposts.

David McWilliams is an economist who hosts the Dalkey Book Festival (dalkeybookfestival.org), which kicks off next week on Bloomsday in Dublin. His Joycean essay will be published in ‘The Book About Everything: Eighteen Artists, Writers and Thinkers on James Joyce’s Ulysses’ by Head of Zeus

This article has been amended since original publication to reflect that Joseph Schumpeter wrote of ‘creative destruction’, not ‘creative disruption’

More on Joyce and his masterpiece

Ulysses at 100: the birth of the modern

Colm Tóibín examines how James Joyce’s groundbreaking novel overturned traditions of storytelling — and of Irish nationhood

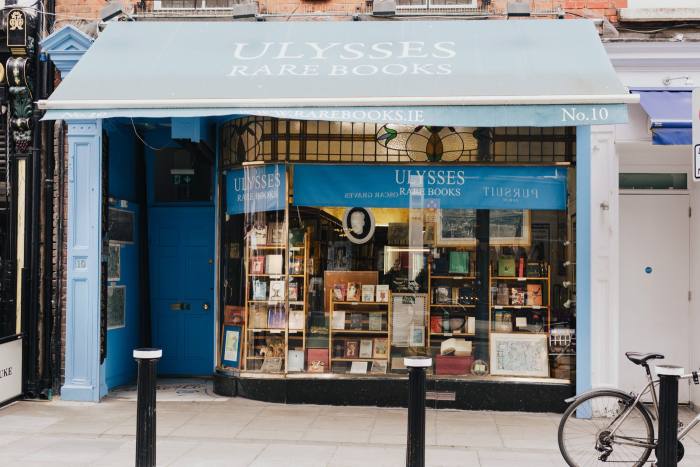

Bloomsday Trip to Ulysses Rare Books

As part of the HTSI ‘cult shop’ series, we venture into the specialist bookshop on Dublin’s Duke Street dedicated to Irish works

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Letter in response to this article:

Greek philosophers can do moneymaking — if pressed / From Alec Burt, Manchester, UK