It was the only time Carl Busch, now 85, had ever seen his father cry.

He was 4 years old in early December 1940, living on a 120-acre farm in Jefferson County, Indiana. His family got a knock on the door. They had 30 days to uproot their lives and clear the property.

The federal government dropped the same bombshell on 500 other families in southeastern Indiana that week, who suddenly found themselves war refugees.

Their homes, schools, churches and cemeteries across 55,000 acres in Jefferson, Jennings and Ripley counties would soon be bought by the government and turned into an army weapons testing ground, the War Department told a meeting of local, state and federal leaders at the Jefferson County courthouse the evening of Dec. 5, 1940.

Busch's father expected to live out his days on the farm, which had been in the family since at least Busch's great grandfather's time. During the Great Depression, Busch's family lost $10,000 in a bank failure, or about $200,000 in today's dollars. And then the knock on the door came.

"It just broke him," said Busch, who now lives in Greensburg. His father died in 1950 at 64 years old.

Newspapers reported the formal announcement Dec. 10. A year and a day later, the United States officially entered World War II.

"With the swiftness of modern blitz warfare," wrote The Indianapolis Star on Dec. 14, 1940, "families whose lives have been spent in this rolling Indiana country must pack up and move."

Morose shock swept communities. The government would pay for their property and relocation expenses, but it would not buy farmers' crops or a businessman's stock.

It was expected the entire area would be swept clean within 45 days, The Indianapolis News reported on Dec. 10. This would become known as Jefferson Proving Ground — "the great proving ground of the Midwest," the Star wrote days earlier.

At the time, there was just one other, in Aberdeen, Maryland, which still operates today. More would be built throughout World War II.

Engineers had been designing such grounds for two decades, but its location was not decided until a month before the announcement, The Indianapolis Star reported in February 1941. A War Department representative told the newspaper the location was selected because of its proximity to ammunition manufacturers in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois and Missouri.

The removal of longtime residents went mostly according to the government's schedule — at the end of January, The Indianapolis Star reported the last of the acreage would be under contract within 10 days. Some families held out longer, like Busch's, who stayed until March waiting for the auction to wrap up on the farmland they wanted to purchase in Decatur County.

But the payments weren't so timely. Checks were not promised for another month after the residents' removal. Many farmers had to borrow money to be able to move elsewhere, forced to pay interest and use their contracts with the government as collateral. Meanwhile, owing to sudden demand, land prices in surrounding counties had skyrocketed.

The Jefferson land acquisition left other complications in its wake.

Bodies buried in cemeteries had to be moved. Tenured teachers who lost their jobs on the proving ground area lost their tenure. The grab wiped out three quarters of Monroe Township, Jefferson County, leaving just 58 families on an eastern tip of township and 15 families on a west side. The tiny township still exists.

All the while, the office of the inspector general was investigating the acquisitions on suspicion that the real estate and title companies brokering the deals were collecting excessive commissions.

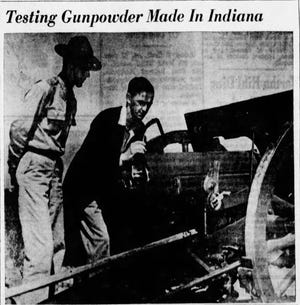

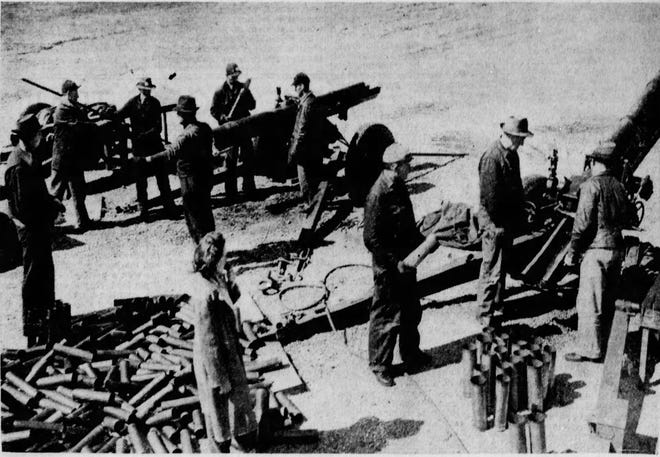

By winter's end, the War Department came to a compromise with the brokers over the commission rates. Ammunition testing began as early as May 1941, and the proving ground officially opened for public viewing in November. The construction project employed about 3,000 people.

At least one historical landmark was saved, but not without effort. The congregation of Liberty Christian Church in Jefferson County, a house of worship since colonial times, paid $2,000 to relocate their building from just inside the proving ground area to a new location 100 yards north.

This money came from what the War Department had paid for the church's building and four acres. The government initially resisted the congregation's idea to relocate, out of impatience to get construction started. It took a resolution from the Indiana General Assembly, in March 1941, to change their minds.

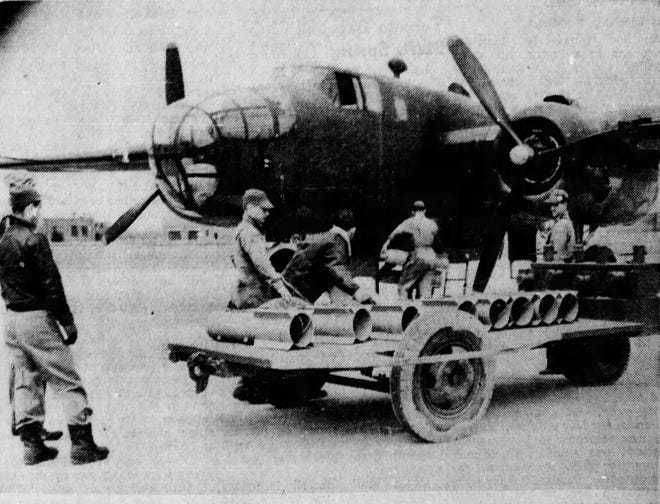

If undertaken today, the laboratory for testing the quality of every type of weapon U.S. troops used in warfare — namely, cannons and bombs — would have cost about $282 million to construct. It would go on to test artillery for American warfare for another 50 years.

"All day long the big guns roar, reverberating for miles," The Indianapolis News described the Jefferson Proving Ground in 1943. "Aerial bombs shake the countryside, rattling windows for many miles from the military reservation. ... Unless the ammunition meets specifications, it does not go overseas."

In later years, as bigger war operations demanded more of the Jefferson Proving Ground, this wasn't always the case. Sometimes ammunition would get loaded onto ships to head to Vietnam before workers in Indiana, like data cruncher Mike Moore, got to test the batch; once they did, faulty ammunition aboard the ship was dumped into the ocean.

Moore still lives in the house his family bought in Madison while he worked at the proving ground from 1974 to 1994. When they'd be shooting artillery, the windows in the town would rattle — so much so that locals called Madison "Boomtown."

"People just got used to it," Moore said. "And after we stopped shooting, they forgot."

Jefferson Proving Ground remained an army testing base until 1995. Soon after, a large portion of the land was leased to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to become Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge. The site is still owned by the U.S. Army, who has conducted studies monitoring radiation levels and soil and water quality in the hopes of decontaminating the area of depleted uranium, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Memory of what happened has largely faded in the broader community, Moore said, except for a dwindling population whose families were uprooted.

A group called the Jefferson Proving Ground Heritage Partnership, dedicated to preserving the oral histories of these families, used to meet monthly, but many members have died. In 2010, they published many of these accounts into a book, "Reminiscences & Reflections: An oral history of dramatic contrast between Hoosiers and the War Department in southern Indiana."

They'd organize reunions of the farming families. Busch's parents never went, but Busch went in later years. "Old Settlers' Reunions," he said they called it.

The last one he remembers was organized for the 75th anniversary. They reminisced about the good times in their old communities. If they had any bitterness, it was long gone, he said.

"It was a very patriotic thing," he said.

"You got to understand, it was a different time," Moore said. "Most of them felt like it was their patriotic duty to leave."

But that didn't make it any less painful. In the late 1990s, with permission from the government, Busch toured the grounds for the first time to see if he could spot any remnants of his family's homestead, despite how young he was when they left. He recognized a weathered stone and concrete water trough, and found one of his father's old tobacco cans.

"I was very young, but it was a very traumatic time," he said. "Those things stick in your memory."

Contact IndyStar transportation reporter Kayla Dwyer at kdwyer@indystar.com or follow her on Twitter @kayla_dwyer17.