Surveillance isn’t just imposed on people: Many of us buy into it willingly.

Imagine, for a moment, the near future Amazon dreams of.

Every morning, you are gently awakened by the Amazon Halo Rise. From its perch on your nightstand, the round device has spent the night monitoring the movements of your body, the light in your room, and the space’s temperature and humidity. At the optimal moment in your sleep cycle, as calculated by a proprietary algorithm, the device’s light gradually brightens to mimic the natural warm hue of sunrise. Your Amazon Echo, plugged in somewhere nearby, automatically starts playing your favorite music as part of your wake-up routine. You ask the device about the day’s weather; it tells you to expect rain. Then it informs you that your next “Subscribe & Save” shipment of Amazon Elements Super Omega-3 softgels is out for delivery. On your way to the bathroom, a notification bubbles up on your phone from Amazon’s Neighbors app, which is populated with video footage from the area’s Amazon Ring cameras: Someone has been overturning garbage cans, leaving the community’s yards a total wreck. (Maybe it’s just raccoons.)

Enjoy a year of unlimited access to The Atlantic—including every story on our site and app, subscriber newsletters, and more.

Standing at the sink, you glance at the Amazon Halo app, which is connected to your Amazon Halo fitness tracker. You feel awful, which is probably why the wearable is analyzing your tone of voice as “low energy” and “low positivity.” Your sleep score is dismal. After your morning rinse, you hear the Amazon Astro robot chasing your dog, Fred, down the hallway; you see on the Astro’s video feed that Fred is gnawing on your Amazon Essentials athletic sneaker. Your Ring doorbell sounds. The pills have arrived.

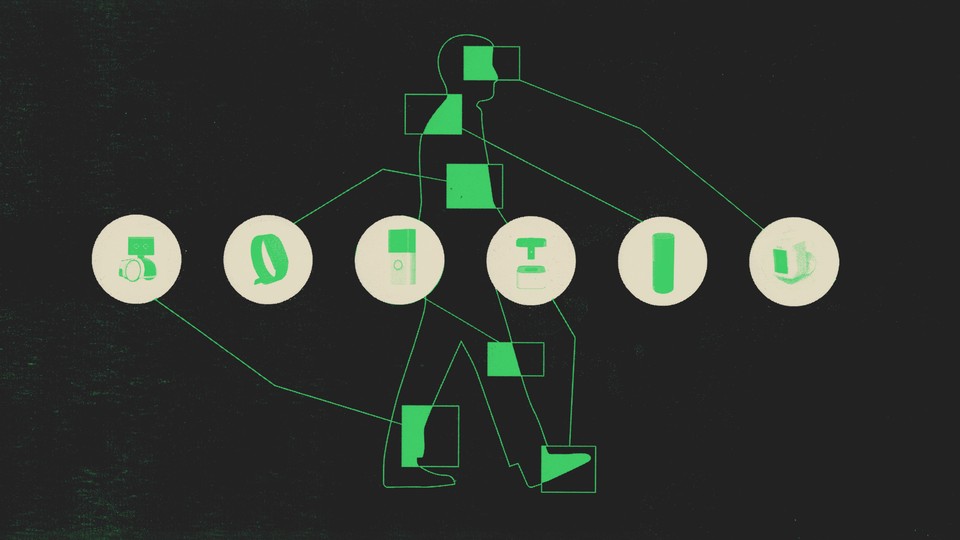

It would be a bit glib—and more than a little clichéd—to call this some kind of technological dystopia. Actually, dystopia wouldn’t be right, exactly: Dystopian fiction is generally speculative, whereas all of these items and services are real. At the end of September, Amazon announced a suite of tech products in its move toward “ambient intelligence,” which Amazon’s hardware chief, Dave Limp, described as technology and devices that slip into the background but are “always there,” collecting information and taking action against it.

This intense devotion to tracking and quantifying all aspects of our waking and non-waking hours is nothing new—see the Apple Watch, the Fitbit, social media writ large, and the smartphone in your pocket—but Amazon has been unusually explicit about its plans. The Everything Store is becoming an Everything Tracker, collecting and leveraging large amounts of personal data related to entertainment, fitness, health, and, it claims, security. It’s surveillance that millions of customers are opting in to.

Don’t miss what matters. Sign up for The Atlantic Daily newsletter.

I won’t be one of them. Growing up in Detroit under the specter of the police unit STRESS—an acronym for “Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets”—armed me with a very specific perspective on surveillance and how it is deployed against Black communities. A key tactic of the unit was the deployment of surveillance in the city’s “high crime” areas. In two and a half years of operation during the 1970s, the unit killed 22 people, 21 of whom were Black. Decades later, Detroit—with its Project Greenlight web of cameras and a renewed commitment to ShotSpotter microphones, which purport to detect gunfire and help police respond without a 911 call—continues to be one of the Blackest and most surveilled cities in America. My work concentrates on how surveillance mechanisms are disproportionately deployed against Black folks; think of facial recognition falsely incriminating Black men, or the Los Angeles Police Department requesting Ring-doorbell footage of Black Lives Matter protests.

Recommended Reading

The conveniences promised by Amazon’s suite of products may seem divorced from this context; I am here to tell you that they’re not. These “smart” devices all fall under the umbrella of what the digital-studies scholar David Golumbia and I call “luxury surveillance”—that is, surveillance that people pay for and whose tracking, monitoring, and quantification features are understood by the user as benefits. These gadgets are analogous to the surveillance technologies deployed in Detroit and many other cities across the country in that they are best understood as mechanisms of control: They gather data, which are then used to affect behavior. Stripped of their gloss, these devices are similar to the ankle monitors and surveillance apps such as SmartLINK that are forced on people on parole or immigrants awaiting hearings. As the author and activist James Kilgore writes, “The ankle monitor—which for almost two decades was simply an analog device that informed authorities if the wearer was at home—has now grown into a sophisticated surveillance tool via the use of GPS capacity, biometric measurements, cameras, and audio recording.”

The functions Kilgore describes mirror those offered by wearables and other trackers that many people are happy to spend hundreds of dollars on. Gadgets such as Fitbits, Apple Watches, and the Amazon Halo are pitched more and more for their ability to gather data that help you control and modulate your behavior, whether that’s tracking your steps, looking at your breathing, or analyzing the tone of your voice. The externally imposed control of the formerly incarcerated becomes the self-imposed control of the individual.

Make your inbox more interesting with newsletters from your favorite Atlantic writers.

Amazon and its Ring subsidiary deny allegations that their devices enable harmful surveillance and deepen racial inequities. “Ring’s mission is to make neighborhoods safer, and that means for everyone—not just certain communities,” Emma Daniels, a spokesperson for Amazon Ring, said in response to a request for comment. “We take these topics seriously, which is why Ring has conducted independent audits with credible third-party organizations like the NYU School of Law to ensure that the products and services we build promote equity, transparency, and accountability. With respect to Halo, no one views your personally identifiable Halo health data without your permission, and Halo Band and Halo View do not have GPS and cannot be used to track individuals.”

Here, it’s useful to remember that contexts shift very quickly when technology is involved. Ring approached the NYU School of Law in 2020 to audit its products—specifically, their impacts on privacy and policing. That report came out in December 2021 and promised to produce greater “transparency” where the company’s partnerships with law enforcement are concerned. This past July—just seven months later—Senator Edward Markey released a letter indicating that the company had given doorbell footage to police without the owners’ consent 11 times this year alone. (Amazon did not deny this in a statement to Politico, but it stressed that it does not give “anyone unfettered access to customer data or video.”)

And remember, GPS tracking isn’t the only form of surveillance. Health-monitoring and smart-home devices all play a role. Consumers may believe that they have nothing to fear (or hide) from these luxury-surveillance devices, or that adopting this technology could only benefit them. But these very devices are now leveraged against people by their employers, the government, their neighbors, stalkers, and domestic abusers. To buy into these ecosystems is to tacitly support their associated harms.

Read: The doorbell company that’s selling fear

Hidden below all of this is the normalization of surveillance that consistently targets marginalized communities. The difference between a smartwatch and an ankle monitor is, in many ways, a matter of context: Who wears one for purported betterment, and who wears one because they are having state power enacted against them? Looking back to Detroit, surveillance cameras, facial recognition, and microphones are supposedly in place to help residents, although there is scant evidence that these technologies reduce crime. Meanwhile, the widespread adoption of surveillance technologies—even ones that offer supposed benefits—creates an environment where even more surveillance is deemed acceptable. After all, there are already cameras and microphones everywhere.

The luxury-surveillance market is huge and diverse—it is not just Amazon, of course. But Amazon is the market leader in key categories, and its language and product announcements paint a clear picture. (Note also that Apple and Google have yet to advertise an airborne security drone that patrols your hallways, as Amazon has.)

At the bottom of its press releases, Amazon reminds us that it is guided by four tenets, the first of which is “customer obsession rather than competitor focus.” It would be wise to remember that this obsession takes the form of rampant data gathering. What does it mean when one’s life becomes completely legible to tech companies? Taken as a whole, Amazon’s suite of consumer products threatens to turn every home into a fun-house-mirror version of a fulfillment center. Ultimately, we may be managed as consumers the way the company currently manages its workers—the only difference being that customers will pay for the privilege.