This year, films and TV shows like Pearl and Bad Sisters are channelling female rage and questioning gendered stereotypes with their violent anti-heroines, writes Miriam Balanescu.

W

When, in 2017, the directorial duo Scott McGehee and David Siegel announced their plans to create a female version of Lord of the Flies, they were roundly mocked on social media. William Golding's 1954 novel famously features a group of boys who descend into barbarism after being stranded on an island. Critics of McGehee and Siegel's project argued that girls would never exhibit the same savagery in such a situation. One sneered, "What are they going to do? Collaborate to death?"

More like this:

- Why 1922 horror Haxan still terrifies

- The world's most misunderstood icon

- The women being demonised on screen

And yet, there is a long legacy of violent women in culture, from Euripides' play Medea, the ancient Greek myth where a wife seeks bloody revenge on her unfaithful husband, to Mary Elizabeth Braddon's 1862 novel Lady Audley's Secret, where a woman's murderousness is explained as insanity, to film femmes fatales such as Kathie Moffat in Out of the Past (1947). On screen, violent women have prompted fierce debate. A Question of Silence (1982), about three women's unexplained murder of a shopkeeper, was controversial upon its release, but later deemed a feminist classic. Glenn Close's Alex in Fatal Attraction (1987) was alleged by Susan Faludi in her 1991 book Backlash to have been made the scapegoat for a man's actions – while also inspiring the misogynistic term "bunny boiler". Thelma and Louise (1991), which starred Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon as women on the run whose destructive spree is triggered by an attempted rape, was, while praised by feminist critics at the time, variously branded "toxic feminism" by John Leo in Time magazine and unfeminist by Sheila Benson in the LA Times. Basic Instinct (1992), meanwhile, sparked protests from the LGBTQ+ community for stereotyping lesbians as vicious, though Sharon Stone's was lauded as "one of the great performances by a woman in screen history" in an essay by Camille Paglia.

Glenn Close's Alex in Fatal Attraction (1987) inspired the misogynistic term "bunny boiler" (Credit: Alamy)

Since the birth of cinema, male violence has provoked less gendered controversy. Colonial westerns and Hollywood war films promoted violence as heroism and a rite of passage into manhood, as argued by writers such as Ralph Donald. This legacy remains, and numerous studies have found that men prefer violent films. Though there have been many filmic portrayals of toxic masculinity and its associated violence – American Psycho (2000) or A Clockwork Orange (1971), for example – male screen brutality, especially in thrillers or action films, has been widely accepted and fostered the idea that aggression is a male trait. In fact, a 2014 study from The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania found that 90% of the highest-grossing movies across a 25-year period had a segment of violence – and relatively little of that is enacted by women.

They, by contrast, have been variously stereotyped as virtuous, weak or passive, and sidelined in famous franchises such as James Bond and Indiana Jones. And when women are violent, it is usually only after they are mistreated by men. A dominant strain of female screen violence in the last 30 years has been "sexualised, hyper-personal revenge in response to rape or loss of a child," Dr Lisa Coulthard, professor in film studies at the University of British Columbia, tells BBC Culture; she cites Kill Bill (2003), where "the Bride" (Uma Thurman) seeks payback against a band of assassins after she becomes their target, in the process apparently killing her unborn child, as an example. "This feminises the violence as it aligns with stereotyped notions of female purity, emotionalism and ties to child rearing. [Characters'] violent vengeance is deemed appropriate or acceptable because of the level of violence that precipitated their actions," she says.

Films such as the first two parts of Ti West and Mia Goth's X trilogy (Pearl, pictured) are presenting violent women in a different light (Credit: Christopher Moss)

This year, a number of films, such as The Woman King, Piggy, and the first two parts of Ti West and Mia Goth's X trilogy are presenting violent women in a different light. While these films do not condone violence, they portray it in a way that calls gendered stereotypes into question and champion female rage, particularly over male aggression. This new wave comes amidst deep concern and anger over the prevalence of male violence against women, with several high-profile cases worldwide, such as that of Chinese vlogger Lamu or the kidnapping and murder of Sarah Everard in the UK. Even more recently, the murder of a young woman in a subway in Seoul has precipitated protests against femicide in South Korea. As women challenge male violence both on screen and in real life, new films and TV series are reflecting this. "There is a turn in recognising female power and [women's] willingness to fight that has shifted the landscape in recent years," says Coulthard. "Across the world, women are paying the price of moves to limit and control female rights and choice and freedoms, and they are rising up to fight back."

For contemporary female directors, in particular, portraying violent women is often a means towards realising female empowerment on screen. In Ana Lily Amirpour's Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon (2021), we are urged to "forget what you think you know" as a psychiatric patient discovers she possesses telekinetic powers. The film's opening sequence has all the trappings of a classic horror, as Mona (Jeong Jong-seo) bids hospital staff to gouge themselves with nail clippers or thrash their heads against television screens, but evolves into an unexpectedly heart-warming quest for human connection. The powers of Amirpour's protagonist enable her to approach a variety of seemingly unsavoury male characters with the certainty that they pose no threat. The Iranian-American director's 2015 debut, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, was a biting tale of a bloodthirsty woman (Sheila Vand) roaming the streets of the fictitious "Bad City" by night. In a cunning subversion of typical power dynamics, she is pursued by men who are shocked to discover that they are prey not predator to this chador-clad vampire.

Ana Lily Amirpour's 2021 horror Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon evolves into a heart-warming quest for human connection (Credit: Sky UK / Alyssa Moran)

In both films, Amirpour uses violence to liberate her female protagonists from the danger men may, in real life, otherwise represent. "With my storytelling, I want to enter into a dream world, a fantasy," Amirpour tells BBC Culture. "The thing I'm looking for in all my movies is to find freedom, to constantly define freedom – it's not just one thing – to go after it, then deconstruct it."

Ti West and Mia Goth's horror film Pearl, out now in cinemas in the US, captures a different kind of female empowerment through violence; set in 1918, it stars Goth (who co-wrote the script alongside director West) as the titular anti-heroine, a young woman who spies a way out of her stifling existence nursing her catatonic father under the watchful eye of her domineering mother. Pearl hankers after stardom and when a regional revue competition arrives in town, she is willing to put an end to anyone who gets in the way of her ambitions – and we root for her all the way.

Elsewhere, female violence on screen is depicted as a means of dispelling still-entrenched notions around women's fragility and weakness by portraying them as anything but. The incredulity at the idea of female brutality that met McGehee and Siegel's Lord of the Flies project encouraged screenwriter Ashley Lyle to prove sceptics wrong with her series, Yellowjackets, whose first season featured poisoning, guns and even (suggested) cannibalism in depicting the aftermath of a plane crash that maroons a girls' soccer team in a forest. While these conditions are extreme, by skipping also between the girls' future lives as adults and flashbacks to their pre-crash teenagerhood, Lyle makes a convincing case for the brutality women are capable of, whatever the situation. Yellowjackets has been a huge commercial success, becoming Showtime's second most-streamed show in its history. Lyle has pinned its popularity on the way it encapsulates a certain mood, telling Indiewire: "There was something about coming toward the end of the lockdown stage of the quarantine and everybody hitting an exhaustion point – maybe people wanted an outlet for their discomfort with the world around them or for their anger or their feelings of dread."

Getting even

"We have seen depictions of women in groups 'going feral', but perhaps the difference is that kind of media has often been hidden," Janice Loreck, author of Violent Women in Contemporary Cinema, tells BBC Culture. "It's B-grade cinema and it's not mainstream or popular."

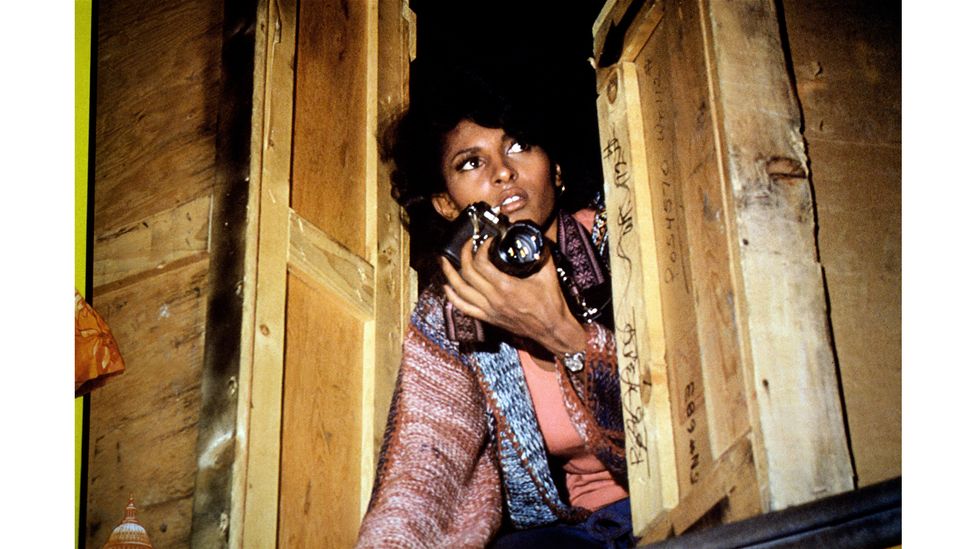

The low-budget, lurid "exploitation" movies of the 1960s and 70s, an umbrella genre which capitalised on sensationalism and controversy to rake in profit, were the first cinematic movements to focus on female brutality. It was often an excuse to marry gratuitous nudity with graphic violence, seen through what feminist theorists have termed the "male gaze" – the perspective of heterosexual men. In Caged Heat (1974), supposedly criminal, "renegade" women are imprisoned and subject to the rape and abuse of a callous doctor (Warren Miller). Foxy Brown's (1974) protagonist (Pam Grier) only turns to violence when her boyfriend is murdered; in the process of seeking revenge, she is drugged, raped and nearly sold into sex slavery. Female violence was either portrayed as exceptional or explained away as a product of male control, as in Cannibal Girls (1973) where the actions of flesh-hungry women are orchestrated by a rogue reverend. While links have been drawn between the "blaxploitation" genre and the Black Power Movement, with Pam Grier particularly hailed as a cinematic icon, and women occasionally have power in such films, they are, in equal measure, on the receiving end of exploitation for the pleasure of certain male viewers.

The low-budget "exploitation" movies of the 60s and 70s like Foxy Brown were the first to focus on female brutality (Credit: Alamy)

The belittling of violent women also goes beyond maltreatment. "The production code in Hollywood created strict rules about what could and could not be shown," says Coulthard. "In my fight scene research, it is difficult to find a female fight scene before the 1980s and, when we do, their punches are slaps or light touches – it's not to be taken seriously."

Emerging from this pattern of abuse and revenge, the slasher and rape-revenge genres went to ever more extreme lengths in their torturing of women. Violence at the hands of men rather than women is often given the most screen time, with Meir Zachi's I Spit on Your Grave (1978), about a woman taking revenge on a group of men who have raped her, featuring the longest rape scene in film history, totalling 25 minutes. The term "final girl" – coined by critic Carol Clover – describes the last woman standing, in horror films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Scream (1996). Unlike her friends, who are punished with death for their sexuality, she is usually virginal and virtuous and emerges the sole survivor of the slasher movie. While her companions are cruelly killed off one by one, she survives, enduring all manner of torments before at long last – and only sometimes – being allowed to strike the final blow to the killer.

The term "final girl" – coined by critic Carol Clover – describes the last woman standing in horror films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Credit: Alamy)

Across genres, from cop dramas to action movies, violent female protagonists have also been sexualised for the benefit of male viewers, from rape-revenge drama Lipstick (1976), where a glamorous model seeks vengeance, to Tomb Raider (2001), where Angelina Jolie plays the scantily-clad video game character Lara Croft. Tellingly, Luke Dawson's review in men's magazine Gear of action-thriller Transporter (2002) insisted, "director, writer and producer Luc Besson knows better than most how to make a beautiful woman even more beautiful: arm her to the teeth". One need only look at the posters for Zachi's film and its subsequent remakes in 2010, 2013 and as recent as 2015, on which the protagonist's clothes have been torn so as to nearly entirely expose her body, to find evidence of how female ferocity has been shaped to suit the tastes of certain male audiences.

'Articulated anger'

The horror of violent women on screen has often been associated with the female body. Think Carrie (1976), where a girl's first period is an omen of the telekinetic monster she is soon to become, or Jennifer's Body (2009), where a hyper-sexualised highschooler (Megan Fox) seduces victims before consuming them, or Teeth (2007), which draws on the myth of the vagina dentata – translated as a vagina with teeth. Such female monsters spring from male fears of the female body as an unknown. These women are also often alienated by their peers as a freak of a nature.

In her landmark book, The Monstrous-Feminine (1993), Barbara Creed explored how female bodies had been tied to horror and disgust. "Horrors about women play with false cultural associations of women with bodies (and nature) and men with minds (and culture) that go back a very long way," Erin Harrington, lecturer at University of Canterbury and author of Women, Monstrosity and Horror Film, tells BBC Culture. "States such as birth and menstruation remind us that our bodies aren't these perfectly closed and self-contained things that we can transcend through thought – not that male or masculine bodies are 'clean' or 'closed off' either – but fear mixes with fascination. Some writers have argued persuasively that this may come from our own inability to comprehend being born, and coming from someone else's body."

In Jennifer's Body, a hyper-sexualised highschooler (Megan Fox) seduces victims before consuming them (Credit: Alamy)

In creating a character we identify with rather than being fearful of, Amirpour reclaims these tropes in Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon. When the character Bonnie (Kate Hudson), a sex worker who takes Mona in, declares "when it's a full moon, I feel it in my ovaries" on the same night that Mona becomes telekinetic, Mona's destructive abilities are symbolically linked back to menstruation – a cycle often connected in mythology to the lunar phases. "I bleed violently every month and feel pain," says Amirpour. "Every month inside my body, there's a violent war that some people can't understand. Women push humans out. We know violence even deeper, internally."

From the "final girl" to the female monster, cinematic trends over time have reinforced the idea that the violent women is an individual outlier, an exception to the rule of female non-violence, in contrast to the pervasiveness of male violence on screen. With more female directors at the helm, there have been reincarnations of the rape-revenge genre such as Revenge (2017), MFA (2017), Promising Young Woman (2020), Violation (2020) and the forthcoming Take Back the Night, retraining the lens on such narratives from a female perspective. With most surfacing in a post-#MeToo climate, the appeal, for some female directors, of playing out an imagined retribution on screen is hardly surprising.

New releases, however, are venturing beyond the well-trodden route of abuse and vengeance to completely remould the figure of the violent woman – no longer mistreated by men, objectified or othered – to seismic success. Killing Eve, for example, first broadcast in 2018, was an instant hit, with its first episode viewed by 8.25 million within 28 days. The series followed a ruthless Russian assassin working for a mysterious organisation named The Twelve and carrying out her kills in increasingly clever ways. Part of the interest in watching this character was her unpredictability, a traditionally unusual trait for female characters. Villanelle shared this with Fleabag, another celebrated character created by showrunner Phoebe Waller-Bridge who has said that while writing she harnesses "female rage", telling Vogue: "It feels like, recently, a lot of female anger has been unleashed. Articulated anger. Which is exciting for me because I've always found female rage very appealing."

This influx of complex, identifiable female anti-heroes is partly about remedying the lack of such roles in screen history – when the lack of female directors has meant that few female characters have been created with honesty and relatability. In 2022's slasher-satire Bodies Bodies Bodies, which shares an "every woman for herself" set-up with Yellowjackets, a group of teenage girls at a party become ensnared in a fight to the death. So far making $12.1 million at the box office, critics have praised the way in which the film rebels against the virginal "final girl" trope in killing off the men first and keeping its highly sexual, messy female characters alive. "I'm very interested in creating female roles that are more dark," the film's director, Halina Reijn, tells BBC Culture. "I don't feel any urge to create innocent or strong women. I just feel an urge to create someone like Richard III: really great female roles that are juicy and strange, about our weaknesses and most hated fantasies."

In 2022's Bodies Bodies Bodies, a group of teenage girls at a party become ensnared in a fight to the death (Credit: Erik Chakeen)

It's a sentiment shared by Amirpour. "When I get that question [about female violence], I'm afraid someone's going to go write 'a strong female this' and 'strong female that' and it stops meaning something," she says. "We inherit this fear that all women carry from the beginning: 'how do you exist in this big bad world?' Wherever we are, there's always some degree of danger. If I psychoanalyse my films, I can see me giving myself that fearlessness."

Both Reijn and Amirpour are working to topple cinematic tropes without subscribing to a specific genre. For Reijn, camp gore and clumsy violence – a far cry from the choreographed combats of the male-steered John Wick or Bourne franchises – is a way of signalling this. Male violence on screen has often been about male viewers delighting in almost dance-like brawls or exaggerated gore as performative masculinity, whereas, with violent women in recent films, the thrill is more in seeing women subverting stereotypically male genres."The whole film has a layer of irony constantly flowing," says Reijn. "I never wanted the fights to look like glamorous and smooth. I've always wanted them to look a bit awkward and how it would occur in reality."

Finding solidarity

The burgeoning TV industry has also expanded the possibilities for creating nuanced, empathetic characters, with Sharon Horgan's Bad Sisters (currently streaming on AppleTV) a prime example. A band of siblings plot the murder of their brutish brother-in-law and, as the series progresses, Horgan explores the emotional and ethical intricacies of a highly complex moral maze. "We are being invited to identify with violent women more in terms of understanding their motives and their psychology," says Loreck. "There's a real curiosity in viewers to think about what people are capable of, and specifically what women are capable of, in extreme circumstances, because we live in very controlled societies and there are solid understandings of what the different genders are capable of."

Female brutality has only recently found its way onto mainstream television – with rare exceptions such as classic Australian prison dramas Prisoner Cell Block H and Wentworth – but already there are marked differences with film. "There is an interest in exploring and explaining why these women are violent," Loreck says. "That is something that television really allows. With Killing Eve, the personality of Villanelle is the object of fascination in that series."

Killing Eve followed a ruthless Russian assassin who executed her kills in increasingly clever ways (Credit: BBC / Sid Gentle)

This year, Kleo, The Serpent Queen and Swimming with Sharks are other examples of shows using TV's longer time frames to dig deep into such characters' psyches, exploring their relentlessness in pursuing their ambitions and pushing beyond Hollywood's sometimes superficial fascination with violent women. Series like The Wilds (2020), which shares the same premise as Yellowjackets, also use their multi-stranded, multi-character narratives to convey how the figure of the violent woman isn't necessarily just one atypical, exceptional individual, showing instead how women more widely are capable of highly complex, flawed and brutal behaviour.

On film, the steady ascent of the violent-and-yet-relatable female anti-hero has been about broadening definitions of femininity on screen – at its crux, the movement has been about finding solidarity in multidimensional cultural representations of womanhood, and the progression of violent women on to the small screen has the potential to further strengthen this solidarity. "These new series and films are interesting because they explore a range of female violence, often in combination with a nuanced portrait of female group dynamics, something we rarely see," says Coulthard. "These female characters are complex and their violence is part of this complexity. That's what draws the audiences and directors – not the violence, specifically, but the emotional, psychological and character range that these series offer."

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday