In the early days of the westward emigration, before the California Gold Rush, the only permanent white inhabitants on the plains were fur traders, the majority of them French-Americans. Almost all these men married Native American women, with whom they had large families, and the plains Tribes considered them as kin. In the mid nineteenth century, there were about three hundred of these men and their families living along the River Platte and its tributaries. Their offspring were so numerous that they even made up their own band, the Laramie Loafers.

Susan Bordeaux, who in later life would become a vivid chronicler of the last days of this extraordinary hybrid world, was born into one of these families. Her mother, Red Cormorant Woman, was a Brulé-Lakota, and her father was a French-American fur trader, James Bordeaux. Susan’s extended family lived all their lives in and around Fort Laramie, on the Great Plains, in close proximity to the California and Oregon Trails. As a child she was witness to effects of the increasingly large numbers of settlers who made their way west each year.

As the trade in fur declined, former trappers like Susan’s father turned their hands to ranching, opened general stores and ran smithies to service the settlers, while others acted as guides. “There [was] perfect peace among the Indians and the fur traders who had mingled with them in the hunting grounds,” Susan Bordeaux wrote. Vast herds of buffalo roamed the prairies, making it one of the richest regions in the world, and furnishing the Indians’ every need. “The country was dear to them,” she wrote, “The waving grass, the sparkling streams, the wooded hills were filled with life-giving foods that the red man appreciated more than gold.”

Throughout the 1840s, as settlers started to arrive in increasing numbers, Susan’s family adapted. In 1849, James Bordeaux started his own grocery store at Sarpy’s Point, eight miles below Fort Laramie. Trade with the overlanders was brisk. Sometimes he exchanged his own chickens, cows and pigs for the emigrants exhausted horses. The overlanders also offloaded a great deal of their unnecessary furniture, “and it was not a surprise to see some of the finest marble-topped tables, bureaus, tables, stands, and colonial carved chairs in some of the humblest of log cabins along the Oregon Trail.”

In the end, it was not a buffalo, but a lame cow, that would destroy the uneasy truce brought about by the Fort Laramie Treaty.Wherever the fur traders were, there was always music. “Pretty near every Frenchman could play,” Susan would recall, and among them there were many who were “artists with the violin.” Looking back, it seemed to her as if men like her father “were born for gaiety and music; it is life with them and they are never as happy as when the music was on the air and a crowd of people were moving to its rhythm.”

Even in later years, when the troubles came, and this vibrantly cross-cultural world faced its greatest existential threat, the fiddles came out at the slightest provocation. At Fort Laramie there were dances every week. “There were quite a number of half-breed girls, all dressed up in bright calico with ribbons in their hair and on their waists, that could fly around in a quadrille as well as anybody, stepping to the music in their moccasined feet. There were many little girls that were in the swing as well as myself.”

Sometimes even the emigrant men and women would join in, playing the music and dancing with the rest. It was the only sport that the “old timers” enjoyed. “Many times some of the older men were called out to the centre to step off a jig to fast music and they could be sure to do it to perfection.” Stick candy and ginger snaps were passed around, and “we were just as happy and enjoyed it as much as if we were dancing in marble halls with chandeliers with their brilliant rays, as the candles’ light we loved.”

But the discovery of gold, in California in 1848, changed everything. The following year, the “gold-crazed” emigrants came in more numbers than ever before: “a living avalanche sweeping before it all that the Indian prized,” Susan wrote. “The devastation of the game! Many of these emigrants knew they were on Indian soil. They were armed to the teeth. A great many started shooting before they were attacked, which caused the Indians to attack, to scalp and mutilate, resolving to stay the tide of the encroachment at any cost.”

In an effort to address these problems a great council was called. In autumn of 1851, a massive assemblage of Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapahoe and Shoshone assembled at Horse Creek, near Susan Bordeaux’s family ranch. At the council, the US government agents fully acknowledged the damage caused by overlanders. They offered an annuity of goods worth $50,000, to be distributed every year for the next half century, if the plains Tribes would agree to keep within certain geographical boundaries. In return, the Tribes were to allow the construction of roads and military posts along the River Platte, and to allow the safe passage of any settlers making their way along them.

The Horse Creek Treaty—later renamed the Fort Laramie Treaty—of 1851 lasted three years. One of its immediate consequences was a flood of yet more emigrants. In the spring of 1852, 70,000 overlanders departed from the Missouri jumping off points, a greater emigration than ever before seen on the plains. In the same year, Indian Office agents informed them that the promised annuities had been reduced from a period of fifty years, to ten. Not surprisingly, the reaction was one of outrage. The valleys along the Platte River, once a haven for buffalo and other game, were now little better than “mile wide dust highways.” The unthinkable fact that the herds they depended on might one day disappear altogether began to dawn.

Singing her own death chant, Cokawin walked into the Army camp and gave herself up.In the end, it was not a buffalo, but a lame cow, that would destroy the uneasy truce brought about by the Fort Laramie Treaty. The failing animal belonged to a group of Mormon emigrants who were passing close to the fort. It was shot by a man named High Forehead, the guest of a Brulé chieftain, Mato Oyuhi [Scattering Bear] who was camping with his band a few miles away from Fort Laramie. When the news reached the fort, a twenty-four-year old army officer, Lieutenant John Grattan, volunteered to ride out to “crack it to the Sioux.”

Accompanied by twenty-nine heavily armed volunteers and two Howitzer canons, Grattan rode off to the Brulé camp, situated not more than a quarter of a mile from the Bordeaux ranch, to demand that High Forehead be handed over for punishment. When Mato Oyuhi, who had already offered the settler one of his own horses in recompense for the dead cow, refused to hand over his guest, the young lieutenant ordered his troops to open fire on the village. The chieftain, who had turned around and was walking back to his tipi, was shot three times in the back.

For all Lieutenant Grattan’s boast that he could “whip the combined force of all the Indians of the prairie” with just thirty men, only one of them would make it back to Fort Laramie. When Grattan and the rest of his men were found, their bodies had been mangled almost beyond recognition: their heads crushed and their limbs cut off. Grattan’s corpse, which had twenty-four arrows in it, had been so badly mutilated that he was only identified by his pocket watch.

Retaliation was swift and brutal. A veteran US Army General, William S. Harney, was summoned by the War Department and given orders to “subdue” the Lakota. Harney, insisting that the American Indians “must be crushed before they can be completely conquered,” assembled an army of six hundred men, and in August the following year he marched up the Platte River.

Harney soon learned that there was a Brulé village camped at a place called Ash Hollow on a tributary of the Platte River known as Blue Water Creek, within sight of the emigrant trail. When some of their chiefs—including among them Iron Shell, Spotted Tail and Little Thunder—saw Harney’s troops approach they attempted a parley. The men rode out, carrying a white flag as “an insignia of truce.”

Their band had had nothing to do with the murder of Grattan’s troops, but when they saw that the General intended to fight them anyway, they asked for an hour to remove the women and children from the camp, but according to some of the survivors, he did not wait. “Now, I have heard Iron Shell and Spotted Tail and others tell that there was no mercy shown—the firing of the guns started right away as the chiefs started toward the army carrying the white flag.”

The fighting, which took place over an area that extended for more than five miles across the plains, was not so much a battle as a rout.

One of the women who was present at what would become known as the Battle of the Blue Water was Cokawin, “a fine-looking, stately Indian woman,” who was the warrior Iron Shell’s mother-in-law. “When she saw that there was to be no peace, she started to run without a thing, not even her blanket.” The other women, many of them already wounded and bleeding, tried to crawl under the overhanging weeds and grasses along the banks of the river, but Cokawin kept on running. When she looked back, she saw a solider taking aim behind her. The bullet ripped her open, making a wound about six inches across. “She was disembowelled, a gaping wound, and her bowels protruded from her wound as she fell.” Thinking that she was dead, the soldier moved on, looking for others to kill.

Seeing a nearby washout, somehow Cokawin managed to crawl into it, and cover herself with tumbleweed. Tearing off one of the sleeves from her robe, she stuffed it into her wound to staunch the blood. “There she lay all day listening to the guns roar and to the hoofbeats of the horses, the shouting and yelling of the soldiers who came so near at times she thought she would be discovered. Once in a while she could hear a Sioux war cry….It was a desperate time with her people; in her anxiety she almost forgot her wound.”

Eventually, she realized that her people had retreated. Harney’s army had taken seventy captives, all of them women, children and old men who had been too weak to run away. As Cokawin cautiously emerged from her hiding place, all she could see were dead bodies and dead horses in the deserted valley. “There was not a soul on the bloody battle ground.”

The world of peaceful co-existence between the white fur traders and the American Indians was shattered forever.Night was falling, and all this time Cokawin had been without either food or water. Now she saw a little skunk wandering around, “sniffing this and that way.” She caught and skinned it, and then cooked it on a fire that she made with her flint. Although the soldier’s shot had torn open her stomach, she could see that her bowels had not been perforated. Somehow, she fashioned a rudimentary bandage for her wound with a strip of skunk skin.

Knowing that it would be sure death if she stayed where she was, Cokawin began to walk in the direction taken by Harney’s army. Despite her wound, she walked all night, resting many times. Towards morning, when she had walked almost five miles, she began to see the faint outline of the soldiers’ camp.

“Cokawin, the mother-in-law of Iron Shell, nearly reached the camp, she could dimly see the sentries walking their beat back and forth.” She knew then that she had only one option. “Cokawin said that it took a lot of courage; it was like facing death,” she told Susan Bordeaux. “She began to sing a death chant. In Indian life there are songs for everything, but to sing your own death chant is an awful thing—it takes a brave person.” Singing her own death chant, Cokawin walked into the Army camp and gave herself up.

Although the extent of the battle field made it difficult for Harney’s army to count the numbers of the dead, one estimate put it at eighty-six, among them many women and children.

The Laramie Treaty of 1851 was dead in the water. The world of peaceful co-existence between the white fur traders and the American Indians was shattered forever.

_____________________________________

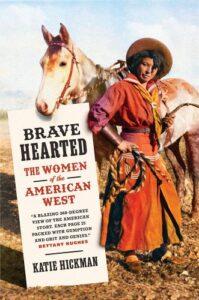

Excerpted from Brave Hearted: The Women of the American West by Katie Hickman. Copyright © 2022. Available from Spiegel and Grau.