A red lever-arch folder, well-loved and battered, sits near me in my office. Throughout my adult life, it has teetered on shelves in various homes, my university dissertation about the women in TS Eliot’s best-known poem, The Waste Land, lying inside – women whose voices felt urgent to me then and still do today.

First published 100 years ago this month in literary journal the Criterion, Eliot’s 434-line poem was instantly notorious. It mixed fragments of languages, religions, references from ancient poems, books, plays, opera and music hall, passages of eloquent speech and scraps of everyday conversations. It translated the restless energy of art movements such as cubism and futurism into vivid words and sounds, uprooting the possibilities of what poetry could be.

It became a landmark for modernism, delving deeply into how fragile people felt in a fast-changing world of shattering empires and realities, especially after the horrors of the first world war. It also reflected Eliot’s state of mind, tortured by the sudden death of his father in 1919, a troubled marriage and his desperation to become an established literary figure (he was still working in a City bank at 33 when he had a breakdown, going to Margate, then a sanatorium in Lausanne, to get treatment and finish writing The Waste Land).

The poem cemented Eliot’s reputation for being a difficult poet, but also communicated profoundly with people. This was partly due to its gothic intensity (catnip for doomy teenagers like the one I used to be) and earwormy lines that still resonate through pop culture (in recent years, you’ll have heard “April is the cruellest month” in episodes of The Simpsons and songs by Blossoms, the Airborne Toxic Event and Hot Chip).

In the poem, various narrators and characters take the reader through shifting landscapes and scenes: deserts, endless plains, rivers of oil and tar, ornate rooms, noisy pubs, the bridges and streets of an unreal city. Their lives were stirred together with references to mythology.

There are lots of women in this mix and they first sang to me at 17 with powerful appeal. They were a motley crew I had never expected to encounter in poetry, including a dreamy “hyacinth girl”, an anxious, manic woman whose “nerves were bad tonight”, gossipy, working-class women in pubs and a silent typist pacing around her flat, alone, after an assault. The urgency their voices retained in my life, and my hunch that they seemed to be sidelined in critical studies, led me to explore them more deeply for a Radio 4 documentary, Hold on Tight: The Women of The Waste Land, to be broadcast later this week.

While making it, I was struck by how many women are revealing new perspectives on Eliot today. They include director Susanna White and producer Rosie Alison, whose brilliant BBC Two documentary TS Eliot: Into The Waste Land (now on iPlayer), a thorough examination of the personal roots of the poem, is packed with women such as the actor Fiona Shaw, who remembers performing the text 70 times in 35 days, poet Hannah Sullivan and fashion model Flesh. For my programme, I interviewed female critics and biographers and younger academics exploring Eliot’s important relationships with women. He wrote passionate, intimate letters to several of these women, some of which reveal fascinating new insights about The Waste Land itself.

Born in 1888 in St Louis, Missouri, Eliot grew up surrounded by women. He was the youngest of seven children with four older sisters (a fifth, Theodora, died at 16 months, two years before he was born). His mother Charlotte was a formidable social worker and social justice reformer, who had given up her dreams of becoming a poet after finishing her studies. She was a protective mother (her son had a hernia from birth and wore a truss all his life), but she was also tough. When Eliot was seven, the third most deadly tornado in US history hit St Louis, killing at least 255 people; his mother trooped her family outside the next morning for a photograph, in which she looks full of resilience. Whenever I read the end of The Waste Land, where a huge storm is preceded by a “murmur of maternal lamentation”, I think of her.

Then comes a woman who Eliot once wrote reminded him of his mother: Emily Hale. They first met when he was a shy 17-year-old and she a budding actor of 14; Eliot confessed his love for her before leaving for England to study in 1914. Later that year, he wrote to poet Conrad Aiken: “I am very dependent on women… and feel the deprivation of Oxford.” Not long after that, he met and quickly married his vivacious first wife, Vivien Haigh-Wood, who suffered from mental and physical health issues for most of her life.

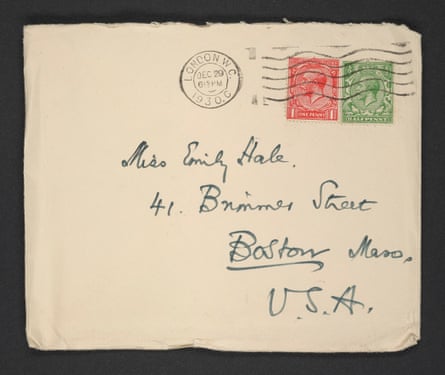

During the breakdown of Eliot’s first marriage, he rekindled the relationship with Hale through letters – 1,131 of them in total between 1930 and 1956. Three months into their correspondence, Eliot said the letters were the only documents that “illuminated” his life and work. In 1956, Hale instructed a friend at Princeton University to keep Eliot’s letters in its archives, instructing that they could only be unsealed 50 years after hers or Eliot’s death. She died in 1969, four years after Eliot. On 2 January 2020, the 13 boxes, and a box of her papers and a short memoir, were finally opened.

The letters are revealing. One, written in 1930, recalls a trip he took with Hale in 1913 to see Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde, after which he was “completely conscious” of love “and quite shaken to pieces”.

A section of a German lyric from that opera, about a moment before the characters fall in love, appears in the first part of The Waste Land, The Burial of the Dead. Immediately after, a character with wet hair and with her arms full of flowers appears, who calls herself the hyacinth girl. Biographer Lyndall Gordon, author of the new book, The Hyacinth Girl: TS Eliot and His Muse, had believed for decades that Hale was the inspiration for this character. “She represented one of the only non-Waste Land moments in the poem for Eliot – one that gave him hope to get out of it.” She first found out about the Hale letters in 1972, when she was a doctoral student at Columbia University, then a hotbed of feminism (Gordon attended Kate Millett’s first public lecture), but these kind of ideas were not trickling into academia, Gordon says. “Thinking of women in relation to Eliot’s life, as I was, was considered not just a distraction or an irrelevance back then but an abomination.”

In 1977, Gordon published Eliot’s Early Years, a sharp-eyed book setting his work in the context of his life. The reviews were savage: one male New Statesman critic said it was full of “gossip and memoirs… the result is a disaster”. “I knew instantly that I wanted nothing more than to live to the day when the letters would be opened,” says Gordon. She was there on 2 January 2020, aged 78, at Princeton’s special collections room. The final line of her new book’s introduction speaks volumes: “I was not disappointed.”

Eliot’s second letter to Hale, in November 1930, states his love for her and its profound importance throughout his life – his first marriage was crumbling at the time and he was still wearing a mourning band for his mother, who had died the year before. He asks Hale to reread the hyacinth girl lines in The Waste Land, plus those that move it towards its peace-seeking conclusion. These, he says, would prove to her that his love for her had grown “and I shall always write primarily for you”.

Eliot’s letters to Hale also revealed how a Waste Land character from its opening lines, Marie, was based on a real person, Marie von Moritz, whom Eliot had befriended in the summer of 1911 in Munich. Von Moritz had told Eliot of her childhood tobogganing in the mountains, how she filled her lonely nights reading and how she would travel south in the winter. Eliot admitted to Hale that he relayed her recollections “almost word for word” in the poem.

The influence of Haigh-Wood on The Waste Land is better known: she inspired the anxious, manic woman in the poem’s second section, A Game of Chess. Less well known is how she approved of the passage: she wrote “wonderful”in the margins of the published drafts of the poem, reissued this year in a centenary full-colour edition. She was also Eliot’s first reader and editor, sharpening one of my favourite passages, in which a nameless woman gossips in broad cockney about someone called Lil, whose husband has recently returned from the war.

In the late 1910s, the Eliots lived directly opposite what is now the Larrik pub in Marylebone, west London, often leaving their windows open to the chatter in the streets, and they had a maid, Ellen Kellond, whose accent and dialect also inspired this section. We’re told that Lil nearly died in childbirth and that she had had an abortion: Haigh-Wood added the lines “the pills I took to bring it off” plus “what you get married for if you don’t want children?” They still feel provocative today.

US academic Megan Quigley is one of the scholars who argue there has been a lack of attention in the past to female subjects in Eliot studies. Editor of the forthcoming Bloomsbury anthology Eliot Now, she noted in a 2019 essay that the 2015 edition of Eliot’s Collected Poems, annotated by male scholars Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue, give “extensive (arguably excessive) annotation” to terms in the poem such as “metropole hotel” and “automatic hand” but contain very little about Haigh-Wood’s contributions to her husband’s work or to the section referring to the abortion.

“What does it mean when ‘pills’ means almost nothing?” she wrote. “Editing shows our values – what we think is important for scholars to know and for students to learn.” The early 20th century was, of course, a time when women’s rights and the suffragette movement were changing the lives and expectations of women. “When I was a student, we were told that a proper study of The Waste Land was about exploring references to mythology, religion and literature – but of course relating these subjects to Eliot’s life, and our reception of it in the present day, is also really revealing.”

Mythological characters in the poem such as Sibyl and Philomel speak to the violence done to the contemporary women in it, too, Quigley argues. The latter is raped and has her tongue cut out, while later a female typist appears, is assaulted by a man, responds impassively and afterwards she’s glad the deed is done.Quigley’s students understandably home in on moments of sexual assault and harassment in The Waste Land today, she says, “especially as these injustices have become so much more visible on campuses in recent years”. They also often debate his misogyny and some sections of the drafts are particularly unpleasant in that regard. One section involves a character called Fresca, who dreams of “love and pleasant rapes”, while French “odours” disguise her “hearty female stench”.

As a reader, Quigley admits she finds these moments “very difficult”. “But there is also sympathy and tenderness for women elsewhere.” When the typist is assaulted, she is observed by a sympathetic mythological character, Tiresias, she says, who embodies both male and female genders – her forthcoming book also looks at Eliot’s place in transgender studies.

Eliot did not always treat women well. Hale thought he might marry her after the death of Haigh-Wood in 1947. But in 1957, he secretly married his secretary, Valerie Fletcher, 38 years his junior, who had long been a fan of his work. In 1960, aware that Hale intended to release her letters posthumously, he asked a colleague to burn those that she had sent to him. He also left a note with the executors of his estate with instructions that it be opened on the same day that Hale’s letters were unboxed.

In this note, he denies her importance in his life, saying they never had sexual relations and how he realised after Haigh-Wood’s death that he was only in love with the memory of the younger Hale, adding: “Emily Hale would have killed the poet in me.” He neglected to mention one of his greatest poems, Burnt Norton from Four Quartets, which directly refers to a 1935 trip with Hale to a Gloucestershire country house of that name and a rose garden there that represented their love.

Any lover of Eliot’s poetry must navigate these tricky areas, as well as the many instances of racism and antisemitism in his work. I find much of Eliot’s misogyny unbearable, but many other scenes featuring women continue to speak to me with a vivid, sad authenticity. Voices such as Emily’s, Marie’s and Vivien’s seem to have stayed with him and by articulating their experiences, he set them in motion, to fly free.

Hale was not the only woman who expected more from Eliot’s friendship. Another book published this month, Mary and Mr Eliot: A Sort Of Love Story, explores his intimate letters, dinners and church visits with Mary Trevelyan, who founded the International Students House, supporting young people overseas and in Britain. Based on a memoir of her 20-year friendship with Eliot from 1938 onwards, The Pope of Russell Square, Trevelyan’s book is “co-written” with American author and critic Erica Wagner, who provides a commentary alongside Trevelyan’s spirited stories and details of their encounters – Wagner found Trevelyan’s accounts of Eliot holding her hand for too long and inquiring often of her mother clear signs of how he played with her emotions. “Men, huh?” Wagner laughs. “I often found it frustrating what she put up with, but people still put up with things like that every day.”

Trevelyan nevertheless gained a great deal from their friendship, Wagner says, and for Eliot, she clearly provided comfort: “That was something Eliot needed. I think he was a man who suffered all his life, but that comfort had to be on his own terms.” But Trevelyan also wanted her words to be heard, Wagner says, and she enjoyed working with Trevelyan’s family to fulfil those wishes. “I was so pleased to help her.” There are many more women who were instrumental in Eliot’s life: Lady Mary Rothermere, who financed the printing of the Criterion, which Eliot edited; Hope Mirlees, a later friend whose 1920 prose poem, Paris, eerily foreshadows The Waste Land; and Virginia Woolf, a supportive friend, whose Hogarth Press published The Waste Land first in book form in 1923. And what struck me most while making my radio documentary is how supportive female academics and writers are of each other’s work on Eliot’s life.

Clare Reihill, who manages Eliot’s estate, said something wonderful to me about Eliot’s second wife, Valerie. Having dedicated the 46 years of her life after her husband’s death to editing his work (Valerie died in 2012), she expressed disappointment at knowing she would not live long enough to see Emily Hale’s letters. “She knew how much Hale meant to him,” Reihill said. “She would have loved to have read them.”

Perhaps this would have surprised her late husband, but this underlines what so many other women are acknowledging today, a century after it was written: that many women’s voices speaking together can help a person’s poetry sing in enriching, new ways. I felt this in my gut at 17 and I still feel it now. Long may Eliot’s women sing to us.

Hold on Tight: The Women of The Waste Land is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday 3 November. Eliot’s letters to Hale will be published online by Faber later this year