We hope that news of a human catastrophe will stir action to end it, but what if too few people believe the messenger? That was the fate of Rudolf Vrba.

In the summer of 2020, video footage emerged showing long lines of prisoners, bound and blindfolded, sitting on the ground at a railway station. The pictures were taken by a drone, and the captives, many of them wearing high-visibility vests, appeared to be Uyghurs. They had apparently been shipped by train to a location that analysts placed in southeastern Xinjiang. Standing over the men were Chinese police in black uniforms. In the short video, which was posted anonymously on YouTube, some of the captives were being led away, their heads bowed, their eyes still covered, their destination unknown.

Enjoy a year of unlimited access to The Atlantic—including every story on our site and app, subscriber newsletters, and more.

Perhaps it was the trains, the aerial shot of the sidings, but the visual echo was immediate. To anyone steeped in the imagery of the Holocaust, when Jews were transported in cattle cars from all across Europe to mysterious camps in the east, the association was hard to avoid. But I also made another connection with the Shoah, one that I imagined gave me a glimpse into the mind of the unnamed leaker of the Xinjiang footage and the hope that drove them to make these images public.

At the time, I was immersed in the story of a whistleblower who had revealed to the world a central part, and perhaps the most notorious aspect, of the Nazis’ “Final Solution.” That man, too, had to hide his identity. He took terrifying risks and endured unimaginable torments, spurred by the conviction that a simple act of revelation—of making the horrific known—would prompt action. He believed that once people knew the shocking truth, they would rise up, instantly and without hesitation, and demand that the horror be stopped.

Read: One by one, my friends were sent to the camps

In researching the story of that messenger, I have come to a bleaker conclusion: The conviction that galvanized him—and doubtless galvanized the source of those distressing images of Uyghur prisoners—rests on a frail foundation. Because the faith that once people know, they’ll act misses something unsettling about human nature: People do not always want to believe the bearer of desperate news—and even when they do believe, they are very capable of looking the other way.

Don’t miss what matters. Sign up for The Atlantic Daily newsletter.

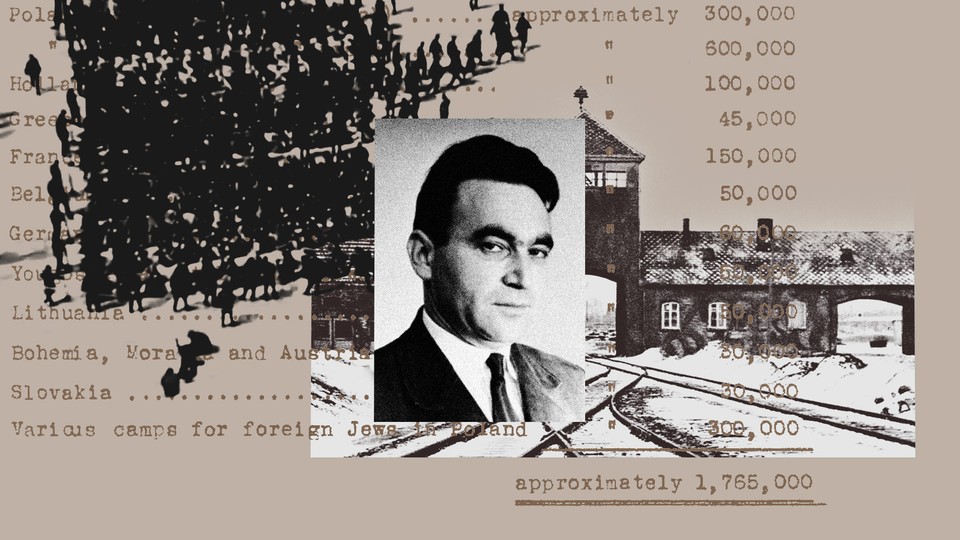

The whistleblower whose story had gripped me was a Slovak Jew born as Walter Rosenberg, though he would later adopt the name Rudolf Vrba. On the last day of June 1942, at the age of 17, he entered Auschwitz. There he would stay for nearly two years—a feat that, by itself, makes Vrba exceptional. The life expectancy of most Jews in Auschwitz was measured in hours; the great majority were dispatched straight to the gas chambers. Even those who were “selected,” in the camp’s parlance, to work as slave laborers were usually dead within a matter of months, victims of a policy the Nazis called “annihilation through labor.”

How Vrba survived is a staggering tale of endurance, resourcefulness, and often random good luck. But it was what he resolved to do with his knowledge of Auschwitz that came to mind when I saw that drone video from Xinjiang.

Vrba worked for 10 months straight on the alte Judenrampe, the railway platform where freight cars packed with bewildered Jewish children, women, and men would pull in night after night. As he watched yet another group line up, ready for selection, Vrba identified a vital component in the Nazi machinery of mass murder—deception. These Jewish deportees had no idea what fate awaited them; they had been lied to at every stage of their journey, in multiple and elaborate ways. Vrba believed that if only those Jews had an inkling of what lay in store, their behavior would change. They might not rise up in revolt (they had no weapons), but they might at least panic: A stampede would create the chaos that could interrupt the smooth operation of the SS killing machine. Vrba resolved to tear through the veil of ignorance and get the word out. He was determined to escape so that he could reveal to the remaining Jews of Europe, and to the world, the meaning of Auschwitz.

Recommended Reading

In April 1944, he and a fellow Slovak, Alfréd Wetzler, came up with an ingenious ruse to break out. It turned on their identification of a flaw in the SS security measures. Their plan required them to hide, barely moving, in a coffin-size hole in the ground inside the death camp. For three days and nights, thousands of SS men scoured every inch looking for them, before finally calling off their search on the presumption that the two men had somehow already gotten away. Vrba and Wetzler then crept from their hiding place and, in the dead of night, inched their way toward the camp’s outer fence and freedom.

From there, the two trekked across the rivers, mountains, and marshland of occupied Poland, without compass or map, traveling only at night to avoid detection. Eleven days later, they reached Slovakia and made contact with the tiny remaining Jewish community. There, in hiding, they wrote a 32-page report that gave the first full account of the Nazi killing center that was running around the clock to eradicate the Jews of Europe.

The Vrba-Wetzler report, as it became known, made its own remarkable journey to reach the desks of Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Pope Pius XII, culminating in diplomatic action that eventually led to the saving of as many as 200,000 Jewish lives. Once the report had made it into the newspapers, both Roosevelt and the pope contacted the regent of Hungary, Miklós Horthy. The U.S. president urged the Hungarian leader to halt the deportation from his country of the last major Jewish community of Europe not yet pulled into the Nazi inferno. This Horthy did—just in time to keep many of Budapest’s Jews from boarding trains to Auschwitz. That makes the Vrba-Wetzler report one of the Shoah’s greatest acts of witness, taking its place alongside those of Anne Frank and Primo Levi.

Make your inbox more interesting with newsletters from your favorite Atlantic writers.

But it did not achieve all that Vrba had wanted it to. When the report was completed, he hoped it would save all of Hungary’s 800,000 or so Jews. Instead, by the time the pope and the president acted, nearly 440,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported to their death.

Read: How I finally learned my name

Part of the problem was prejudice. Jews, after all, were not quite like “us,” and officials in Whitehall and Washington had doubts. “Although a usual Jewish exaggeration is to be taken into account,” wrote one in Britain’s Foreign Office, “these statements are dreadful.” Shortly afterward, another wrote: “In my opinion a disproportionate amount of the time of the Office is wasted on dealing with these wailing Jews.”

In D.C., the report was passed from one government department to another, at a lethargic pace. Eventually, a copy reached the U.S. Army weekly Yank, which had wanted to run a feature on Nazi war crimes. The magazine declined to use the material, which it found “too Semitic.” It requested a “less Jewish account.”

Is it possible that a similar lack of trust and empathy for those deemed insufficiently like “us,” too other, accounts for why the release of that video from Xinjiang did not spur the world to swift and severe action? Could it explain why the international community did not act to save the Rohingya Muslims as they faced genocide in Myanmar in 2016? Was it what allowed the murder of hundreds of thousands of Tutsis at the hands of Hutu militias in Rwanda in 1994?

Of course, each circumstance is specific and presents particular obstacles. The plea that various Jewish leaders attached to the Vrba-Wetzler document, urging the Allies to bomb the railway tracks to Auschwitz, was deemed “impracticable” on military grounds. Likewise, in 2020, no one suggested armed action to protect the Uyghurs: The very notion of picking a fight with the Chinese military would have been dismissed as absurd. On the rare occasions when there has been a military response—NATO’s bombing of Bosnian Serb forces in the Yugoslavian civil war, and then of Serbia itself over Kosovo, in the 1990s; NATO countries’ supply of equipment and training for Ukraine today—a crucial factor seems to be the West’s memory of World War II, which regards criminal aggression in Europe as belonging to an exceptional moral category.

Read: ‘I never thought China could ever be this dark’

But the testimony of Vrba and Wetzler ran into a more fundamental barrier than either prejudice or practicality: a wall of disbelief. The head of the U.S. Office of War Information refused to publish the report on the grounds that no one would believe it, insisting it would undermine the wartime credibility of the U.S. government.

Even the Jewish Council in Budapest could not believe what Vrba and Wetzler were telling them. The Jews of Hungary were the audience the two escapees had most wanted to address, so that those hundreds of thousands would not go quietly and obediently to their deaths. But the council’s president, Samu Stern, wondered if the report was a figment of the imagination of two rash young men. He and his colleagues felt it would be reckless to distribute such an alarmist text—it could cause panic; council members themselves might be disbelieved or face punishment from the country’s new Nazi masters. Officially, the report stayed locked away.

Word did reach some of Hungary’s Jews. A teenager named György Klein saw a copy and went to warn his uncle. Instead of making preparations to escape, the older man became furious. “His face got red; he shook his head and raised his voice,” Klein recalled in a memoir written decades later. Again, disbelief.

When two more Jews escaped Auschwitz in May 1944, their testimony was added to the Vrba-Wetzler report. One of the pair, Czesław Mordowicz, was later recaptured and sent back to the death camp. Even then, inside the cattle car, he tried to warn his fellow Jews what lay in store for them. “Listen,” he pleaded, “you are going to your death.”

But when he urged them to join him in jumping off the moving train, they began banging on the doors and calling the German guards. They attacked Mordowicz and beat him badly. And so they all went to Auschwitz.

Information, Vrba learned, is not knowledge. Before humans will act, they not only have to have the facts; they must also believe them. “I knew, but I didn’t believe it,” said the French Jewish philosopher Raymond Aron, when asked about the Holocaust. “And because I didn’t believe it, I didn’t know.”

When we face a looming catastrophe, especially a moral emergency, something pulls at us, encouraging us to ignore it, to find any excuse not to heed the warning. We are adept at rejecting information we do not want to hear. We may even become angry with the messenger.

Rudolf Vrba fought that impulse, with only partial success. Today, his story has something profound to tell us: The first line of defense against evil and catastrophe is truth, but the truth alone is not enough. It needs believers who will not look away.