Every product was carefully curated by an Esquire editor. We may earn a commission from these links.

There’s only one way to get on Rikers Island and one way to get off—a narrow, forty-two-hundred-foot-long bridge spanning a part of the East River. At the ribbon cutting in 1966, Mayor John Lindsay called it the “Bridge of Hope.” Forty years later, in 2006, the rapper Flavor Flav dubbed it the “Bridge of Pain.”

Purchased from the Rikers family in 1884 for $180,000 (about $5.1 million today), it began life in the nineteenth century as a motley assortment of jails and “workhouses,” or debtors’ prisons. Using fill from the construction of the Manhattan street grid, the city expanded the island from 87 acres to roughly 415 acres.

It was also a massive garbage dump. Residents of Hunts Point in the Bronx could smell it from their homes a mile away, and Upper East Siders could easily see the flames from the burning of mountains of trash. Enormous clouds of rats populated the dump to the point where they challenged dogs, and humans, for control of the island.

Even today, Rikers remains landfill to a depth of roughly ten feet, based on borings conducted in 2009. “They drilled a bunch of holes and all ten feet were garbage, mixed sand with pieces of glass and brick, pieces of wood—everything you can imagine that would be thrown away as materials from a construction site was in there,” explained Dr. Byron Stone, research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

The first jail at Rikers, in the modern understanding of the place, was born in the spirit of reform. In July 1928, seven years after Vincent Gilroy’s broadside, the city fathers unveiled their plan for the Rikers Island Penitentiary. The New York Times described it as a model prison that would correct the evils of the past.

The inscription, placed in 1933, read, “Those who are laying this cornerstone today . . . hope that the treatment which these unfortunates will receive in this institution will be the means of salvaging some lives which would otherwise have been wasted.”

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

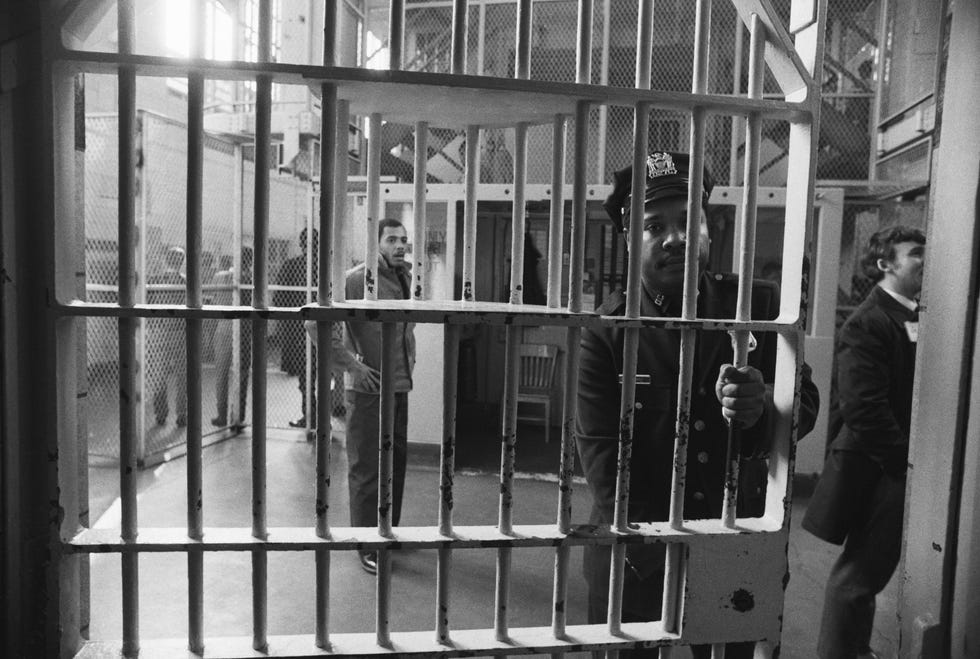

As the decades passed, this purported icon of penology became a forbidding place indeed. Detainees were thrown or jumped from the upper tiers to their deaths, so those floors had to be closed.

Violence ruled.

And over time, it became known by the jailed as the “House of Dead Men.”

But the city stuck with Rikers as the place to leave the people society had deemed worthy of incarceration, the vast majority poor and of color. It was out of sight, hard for visitors to reach, closed, and foreboding.

For some of the hundreds of thousands of souls who have made the passage over the past five decades, a trip to Rikers may be the first time they will sleep somewhere away from home. For others, it’s their only chance for a bed and a warm meal. For some, it might be the place where they find themselves fighting for their lives. And still others may never make it out. The memories of their first day on Rikers are ingrained in the minds of the people who worked, visited, and served time there.

It’s an experience no one forgets.

GRACE PRICE, detained 2011: They literally arraigned me at midnight. It was me and three other people on the bus to Rikers. There was this little crackhead lady falling asleep on my shoulder on the way across the bridge. She was nasty, but I just let her sleep there because it somehow made me feel like I was actually in control of my situation.

COLIN ABSOLAM, detained 1993 to 1996: Going back and forth on those DOC buses over that bridge was traumatic. The bridge is very narrow, and you’re caged up, shackled. If the bus happened to go off that bridge and fall into the water, everyone would die. I mean the correction officers would get out, but you’re in a cage. They would have to open the cage and get the shackles off. There wouldn’t be enough time to do that before you drowned.

GRACE PRICE: The guards on the bus were horrible, and I just kind of sat there quietly sobbing. The guards hated me for that because they don’t like to hear a hysterical woman.

YUSEF SALAAM, detained 1989 to 1994, Central Park 5 case: I can’t really describe in words this horror and this horrible feeling coupled with that horror, but it had a lot to do with the smell of the place. We’re talking about a place that smelled like death, vomit, urine, feces, and like the bad train stations in New York City all wrapped up in one. And one of the first encounters I had with somebody coming up to me while I was inside the holding cell, they were asking me to check out my watch, and I didn’t realize this, but they were trying to steal the watch from me.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

And I remember [the Central Park 5 co-defendant] Antron [McCray] saying, “No, don’t let them check your watch out, man. You know what I’m saying? Like they’re trying to get you, this is a trick, you know?”

DONOVAN DRAYTON, detained 2007 to 2012: I was nineteen years old. I’d never been through prison before. I’ve been through some difficult things, but walking into the unknown and not knowing what’s waiting for you, it’s one of the scariest things. And once you actually get inside and see how it’s running and operating, the environment and all the chaos, you’re just like, “Wow, this is a whole nuther world.”

Donovan Drayton was nineteen when he went to Rikers, where he spent nearly five years pretrial.

EDDIE ROSARIO, detained 1990: When people ask me, what is being locked up like, the most horrible thing about being locked up is that you are being dehumanized on a daily basis. They practically stamp a number on you. In order to navigate the experience, you have to normalize the dehumanization. You have to buy into it in order to survive. That is the most horrible thing about being locked up. You’re never the same person again. Once you internalize it, you project it outward. If you are being dehumanized, that’s how you treat other people. That, to me, is the essence of incarceration: having to buy into the dehumanization.

That, to me, is the essence of incarceration: having to buy into the dehumanization.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

STANLEY RICHARDS, detained 1986 to 1988: I was addicted to crack and on a methadone program and was out on the street robbing for my addiction. When I went to jail after I got arrested, I was in the most emotional pain in my life. And I find myself now in a bullpen with people that I’m going through it with. I’m going through it ’cause I haven’t been able to get my crack, haven’t been able to get my medication, and I am hearing my name being called through the various cells as they process you. So from the point of arrest to the point of getting a bed on Rikers could be something like five days. It’s that intense. No shower. No hot food, none of that. There’s no phone ’cause you’re all in bullpens. You’re basically shoved into a small cell like fifteen by ten and there’s anywhere from like twenty to thirty men shoved in there. So you’re lucky to get a seat. Most are staying on the floor. And most of the people are dope sick. Some are mentally insane or having other medical issues not treated ’cause they’re on the streets.

BERNARD KERIK, correction commissioner, 1998 to 2000: When I got to Rikers the first time, when I crossed that bridge, I thought, God, this is a nightmare. I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to, you know, work there. Instead of one jail (where I previously worked in New Jersey), there’s ten and it looked like a city within a city. And then getting through the process, getting into the facility, meeting the guys on the island, waiting for the inmate. It was just a mess. It was uncoordinated. It was filthy. It was what the reputation was.

KATHY MORSE, detained 2006: I remember being in the holding cell in reception, the one they first put people in when they arrive. There were women in there who were getting dope sick. They were fighting over space to lie on the floor. Another woman had multiple layers of clothing on. I couldn’t figure out why. It was because at that point, when I was there, you could wear your own clothes if they met the criteria in terms of non-gang colors and things like that. So she came to court that day prepared for going to jail. She was wearing enough clothes for her stay. I realized I was unprepared.

DONOVAN DRAYTON: I went in November. It was cold. I remember just being in intake, man. It’s like, “Yo, I’m really stuck in jail, son.” Seeing everybody with their bags and all their stuff. Like your whole life packed up in a bag in a waiting cell, getting ready to be shipped off somewhere. You don’t know where the heck you at, where you going, and they don’t tell you where you’re going until you actually go.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

ROBERT CRIPPS, retired warden, 1983 to 2013: The first couple of weeks I literally had trouble sleeping ’cause you have to get accustomed to working on Rikers Island, you know, with all the gates locking behind you, all the violence, and everything else. Tough job.

Detainees at Rikers were thrown or jumped from the prison’s upper tiers to their deaths, so those floors had to be closed. Violence ruled. And over time, it became known by the jailed as the “House of Dead Men.”

DR. HOMER VENTERS, correctional health services chief medical officer, 2015 to 2017: My first day on the island was in November 2008. It was snowing heavily. And it was just incredibly surreal to hear all the guys yelling out of the [solitary unit called the] Bing. You get out there and all these guys are yelling out. It never stopped. Really. It was just kind of a constant.

KATHY MORSE: I just remember how medieval the reception cells were. The toilet didn’t flush, but people were still using it. They were going to the bathroom or to vomit. It was just a mess. I don’t do drugs so I have never been exposed to that. There were women on the floor throwing up, getting violently sick because they were withdrawing. One woman in the cell had crack hidden in her hair, and it fell out. And they all scrambled around the floor, like it was a piñata that had been opened. That was the first time I had ever seen crack in my life. It was just a horrible experience. And the officers were trying to figure out who brought it into the cell. They did take away what they could, but they only got a portion.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

I just remember how medieval the reception cells were.

KANDRA CLARK, detained 2010: We were in the bullpen, hadn’t even been through intake. And it was dinnertime, so correction officers were eating outside food. Really good-smelling food. A young lady came in and it was right after everybody in the bullpen had been served sandwiches. So she kept saying she was hungry, she was hungry. Correction officers refused her because they said she had just missed the cutoff for dinnertime. Mind you, this is the bullpen so she doesn’t have any other options to get food. The officers were just laughing and eating their own outside food.

She was a young woman. She pushed her hand outside through the bar and she grabbed the garbage can that was sitting next to the bullpen and she pulled it closer to the bars and she reached her hand in and she grabbed out pieces of half-eaten baloney. And she just started eating it out of the garbage. And there had to be ten officers sitting around who just watched her. I was so angry because it was very frustrating to see so many human beings laughing at someone who was just hungry and having no care for her.

You kind of knew this was how it was going to be. There was definitely not relationships being built between correction officers and incarcerated people. It was an us-versus-them kind of thing.

ANNA GRISTINA, detained 2012: The judge decides they were going to put me in protective custody. This experience was coming off the Rikers bus from court. I was told I had three minutes to pack up my stuff. I didn’t get a pillowcase or a bag. I had no way to carry my stuff, so I had to wrap everything in my blanket.

They took me down to the condemned psychiatric ward. This was a place that had been deemed unfit for human occupancy, I learned later from my psychiatrist. I was in there alone. The windows were fused shut. The heat was turned up to 102. I got heatstroke. They had a guard six feet away from me 24/7. They had three men in the Bubble [a glass-enclosed booth where an officer sits to observe the unit]. Every time I took a shower, there were two-inch water bugs and it reeked of cat urine, because there was a cat colony under there. There was no water source other than the orange juice or milk they gave me at meals. When I complained, they leaked a story about wanting to put me in diapers. It was a derogatory story.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Later, it came out I was telling the truth.

There was no air-conditioning, and these were cinder-block cells. I tried to get on the phone but kept getting cut off, so I had no phone access and I couldn’t leave. And there’s no commissary. I couldn’t pick out what food I could eat. One night it got so hot that I was getting a severe heat migraine. I told the guards, but I didn’t even get Advil. I vomited from the heatstroke. There was no cool water. They could see me when I was in the toilet too. There was a row of eight toilets. I had to clean the toilet with shampoo. It was covered in feces.

"You’re basically shoved into a small cell like fifteen by ten and there’s anywhere from like twenty to thirty men shoved in there. So you’re lucky to get a seat. Most are staying on the floor."

KENNY GILMORE, detained 1971: Going through Rikers Island helped me to forget about what I actually had to deal with because it was atrocious. It was in 1971. Being in a holding cell with sixty, sixty-five, seventy people and some were there days before you. Someone was always sick, throwing up, dope sick. The toilets are not flushing, and people are not bathing. It’s crazy.

SIDNEY SCHWARTZBAUM, retired deputy warden, union president, 1979 to 2016: I was twenty-five. I was a street kid, though. In the academy, I was told to be fair, tough, and consistent and give the inmates what they deserve legally by law, but you are the authority figure. You control your housing area and work with adolescents. I was told you have to make sure that nobody assumes the role of authority figure in the inmate population because that’s when the inmates don’t eat, they starve them. They’ll come up and take your tray.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

You make sure everybody gets a phone call. Make sure nobody’s getting bullied. Make sure nobody gets seriously hurt. Make sure nobody escapes and nobody hangs up [takes their life].

This was a place that had been deemed unfit for human occupancy.

STANLEY RICHARDS: And then when you get to the housing area and now you start getting a little normal. You can start making your phone calls.You can start getting a shower. You get your three hot meals; now you’re figuring out, how do I survive in this environment? So from the moment you go into the house, you’re figuring out who’s running the place. Back then we used to call them the house gangs. The guys who controlled all the food, phones, and TVs. They had relationships with the officers.

DIMITRI ANTONOV, detained 2020: The biggest thing was the phone. As soon as I walked in, people started asking me about using the phone. Everybody on Rikers sells their PIN numbers for commissary or other stuff. But you shoot yourself in the foot. You give out your PIN number, and if you’re moved, the guy is going to change your PIN number and take all your minutes. At first, I was giving it out. This one guy kept hitting me up over and over. And I was letting him use it.

Another Russian guy says to me, why are you letting him use it for free? I said I was being diplomatic. He goes, what are you talking about? Every five minutes is a dollar. You are going to end up running out of calls. That’s a bad idea. These guys are going to use up your minutes you could have used to call your lawyer. I was still thinking I would be released any second. But after about two weeks, I realized that wasn’t going to happen, and I stopped giving out free minutes. One guy actually said he felt bad for asking, so he stopped.

His friend came to me and said, yo, you remember giving my boy free minutes? What’s up? He goes, I’ll give you a soup and chips, but you gotta give me the call right now. And he would make the call and take off. And of course I was chasing him to get the soup and the chips. It would always be this big thing [to get paid back].

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

"There was definitely not relationships being built between correction officers and incarcerated people. It was an us-versus-them kind of thing."

JERRY DEAN, detained 1987, 2003: Okay, so I remember 1987. I remember I was going to Rikers Island and I had my nice clothes in the court and my father brought my old clothes just in case I was going to get sentenced that day. I didn’t want to go to Rikers Island with new clothes, ’cause they rob you. They didn’t want to send me to Rikers Island, because that Howard Beach case had just happened and there was a lot of racial tension on Rikers Island. And I said no. I said, I want to go to Rikers and start doing my time. And they sent me to Rikers.

The first day I was there, I was on the phone with my girlfriend. This Dominican kid comes over and hangs the phone up on me, and I knew right then and there I had to fight. I had just turned sixteen, so I was in [the teen jail, the Robert N. Davoren Center]. And I got into it with this Dominican kid, and then we went to the back [where] correctional officers used to let you fight for five minutes. As long as you kept it clean and no weapons, they let you get it off your chest. So me and this kid go in the back and we started fighting. I was a pretty good fighter.

I hit him with some blows and he went down and he said he wanted to take a nap to sleep it off. So he went to take a nap and I said to myself, I was gonna show these kids what happens the next time when one of these little motherfuckers hangs the phone up on me when I’m talking to my girlfriend. I wanted to gain my respect. He was sleeping, so I went over to him and quietly took toilet paper and wrapped it around his legs. Then I set him on fire. He jumped up and he was screaming. But I got my respect, and all of a sudden the correction officers liked me, the other inmates liked me, and they put me on the house gang.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

JACQUELINE MCMICKENS, correction commissioner, 1984 to 1986: Correction officers are mean to inmates, and inmates are mean to correction officers. A man doesn’t haul off and hit a man if he thinks there’s a consequence.

ROBERT CRIPPS: During lunch, there was an alarm and there were inmates fighting. The correction officers had to restrain them and march them down the corridor. I wasn’t involved in it, but that was my first day. It was like, what did I get myself into? They were being marched down the corridor and the inmates were all bloodied up and one of the officers got bloodied up too. It was all pretty violent.

COSS MARTE, detained 2010: I was eighteen. I went to the adult facility. I remember as soon as I walked in the dorm, there were people banging on the glass waiting for me to get in. It was called Broadway because my bed was in the middle. I was the new guy. A couple of gang members came up to me and asked me what I was claiming. If I was part of a gang or not. I told them I’m NFL, which back in the day stood for Neutral for Life. There was a riot that first day. Someone got stabbed with a broomstick on top of my bed. There was so much blood. I remember trying to get new sheets because mine were covered in blood.

In February 2022, criminal justice activists protested outside of the prison, demanding that Rikers Island jail be closed. In 2022, 19 incarcerated people died in Rikers—the deadliest year for people in city custody since 2013.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

EDWARD GAVIN, retired deputy warden, 1982 to 2001: So there was an orange alert, and what that meant was the count was off, which means there may have been an escape attempt. The captain at the time of the academy, Mendoza, he said, you’re stuck. Go over there now on overtime, being that you’re going to be assigned there Monday. So I walk over there, this captain in the control room, he picks his nose; he has a snot on the end of his nose. He goes, “Six lower B, rookie.” I must have looked like New Jack City. I’m walking down there with white gloves in my lapel jacket. I’m walking a quarter mile to the post. I’m brand-new. Right out of graduation. You would think they would say, go home and have a nice graduation day. But no, you’re stuck. Imagine that! They would never do that in the Police Department.

It was my first day. I’m white. I start taking the count. It’s like 3:00 p.m. I’ve got all of six minutes on the job. They [detainees] go, “Yo, punk white boy from Long Island!” I was from Rockland. “New Jack motherfucker!” They were all making fun of me. I’m walking by the cells. The inmate goes, “Yo, New Jack, you, CO, you know that Jamaican CO you just relieved?” I thought about it. I go, “No, what Jamaican CO?” He goes, “CO, you’re Jamaican my cock hard, motherfucker!” I really got into how they talk, the lingo.

So, anyway, the next thing you know, we gotta get them ready for a meal. I don’t even know if I should say this—if I’m going to get in trouble thirty-six years later—but I’m just brand fucking new, so they crack all the cells, sixty on the A and sixty on the B. We put them in the dayroom.

They’re all in there. And everything is fine. Then this Black guy comes on the post. He’s a big guy. He’s got like ten years on the job. And I got like ten minutes on the job. He goes, “Crack the dayroom.” He brings a big kid out. This kid was huge. They start having words. Apparently, this kid disrespected him two hours earlier in a corridor. He’s coming back to tell this kid what time it is. This is how you maintain order. They are now fighting and going at it to the point where my guy’s losing. And I’m thinking, this is not good.

So I go behind the huge kid and jump on him and put him in a full nelson. I take him to the ground. They are still fighting. He was getting the better of my guy until I jumped on him, but now my guy is getting the better of him: boom, boom, boom. In the end, my guy broke his arm and his elbow and the inmate had a broken jaw. Ten minutes into my first day.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

EVE KESSLER, director, DOC public affairs, 2014 to 2017: When I got the job, it was very late 2014. I saw [the political consultant] Hank Sheinkopf at a holiday party. I said, “Oh, hey, uh, you know, I got a job. I’m the new director of public affairs in the New York City Department of Correction.” He said, “Congratulations, you won’t make a difference. Correction has been a corrupt department for thirty-five years.” And that proved to be true.

JOHN BOSTON, retired director, Legal Aid Prisoners’ Rights Project: People were getting into fights all the time. Sanitation was not maintained. The food service operation was incredibly badly run. The level of chaos, the level of dirt, just the squalor of the housing areas where you’ve got double bunks all over the place. I mean, you’ve seen photographs from Mississippi and Alabama when they were at their most overcrowded or California before they got their population cap. And it was the same story.

KENNY GILMORE: You don’t want to sit down; you don’t want nobody to touch you. You really have to establish yourself. You’re looking at the madness of it. And then you go from the holding pens to Rikers Island, and this is where we were corralled. That’s a good word. We’re corralled into a reception area. And they’ll say, “Okay, everybody take their stuff off. We are processing you in now,” and to be processed was so degrading because they strip-search you, and when they strip-search, you’ve got to take everything off to check for contraband. If we’re carrying any contraband, no one is checking for any diseases or anything like that. It’s all about security. They check you, they talk to you dirty, they try to humiliate you. They don’t care who you are. In fact, most of them don’t even know.

MARTIN HORN, correction commissioner, 2002 to 2009: It was all about bullying. If you were a single guy and walked into a cell-block, somebody is going to walk up to you and say this is a Blood house. Joey is our leader. We’re loyal to Joey. Here’s the deal. If you want to sit on this chair to watch TV, you gotta give us a blow job or we’re gonna fuck you in the ass.

KENNETH SAMUELS, detained 1994 to 1996: My first night in Rikers, I got surrounded by some gang members. They thought I was a member of the Bloods. At that time I didn’t know what that was. They thought I was joking around. They asked me if I was a Five Percenter. Then I saw somebody I went to school with, and he told them he knows me and I wasn’t part of a gang or anything like that. You had to ask to be on the phone and I didn’t understand that. I got into a couple of fights over that. On Rikers Island, you gotta basically help yourself. There was no counseling at that time or anyone you can really talk to.

SIDNEY SCHWARTZBAUM: The first day, I did my job. I was happy. I got through it; there were no incidents, no fights. But I remember one day taking it personal, about an inmate who beat the crap out of another inmate and bloodied him up really bad. And over the course of a few months, I started to see more blood and violence, and I could see that my mind started to adapt as a defense mechanism, to deaden, because I was starting to take it personal that if it happened on my tour, I wasn’t doing my job. I’m not protecting them. But after a while you realize that it’s inevitable, that it’s a high-crime area. These guys are going to hurt each other, that’s what they do, you know? So I started to create defense mechanisms in my head to allow me to deal with it.

From the book RIKERS: An Oral History by Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, to be published on January 17, 2023 by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau.

Graham Rayman is a journalist who writes mainly about criminal justice and policing. He has won multiple journalism prizes over his thirty-year career. He has worked at The New York Daily News and before that The Village Voice, Newsday, and New York Newsday. He is the author of The NYPD Tapes.

Reuven Blau is a senior reporter at The City. He has previously worked at the New York Daily News, the New York Post, and the Chief-Leader. He is known as the dean of Rikers reporters.