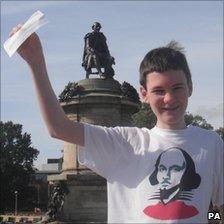

Christopher Guerin - once named Britain's brainiest kid - is now head of maths at a secondary school

A four-year-old boy made headlines this week after becoming the UK's youngest member of Mensa, the society for people with sky-high IQ.

But what happens to children like Teddy when they grow up?

Two decades ago, Christopher Guerin was in a similar position to Teddy. He was crowned Britain's brainiest kid aged 12 in 2002, beating thousands of other kids on the TV show.

"It was something that me and my family didn't expect at all," says Mr Guerin, now 32, from Birmingham. "My face was in all the papers, on the BBC News website." (You can see our report from the time here.)

With an IQ of 162, he was already a member of Mensa - something he joined after watching an episode of The Simpsons and seeing Lisa Simpson sign up.

Mensa accepts people who score within the top 2% of the general population in an approved intelligence test.

His win opened up plenty of opportunities, including being invited to watch his beloved Aston Villa play with the club's chairman, and a free trip to Ireland from the Irish tourist board - both his parents were from there.

There was an expectation on him to excel - but he didn't find it to be a negative. In fact, it spurred him on. "I personally responded well to that," he says.

"I think even if I hadn't won it I still would have wanted to excel at what I was doing anyway but it definitely gave another angle of it.

"I went to a state grammar school, so that meant that being academically competitive was a big part of the school ethos anyway, so it was a really good environment to be part of and most people responded to it positively."

Britain's brainiest kid went on to achieve three masters degrees including one from Cambridge, and is currently studying for his PhD.

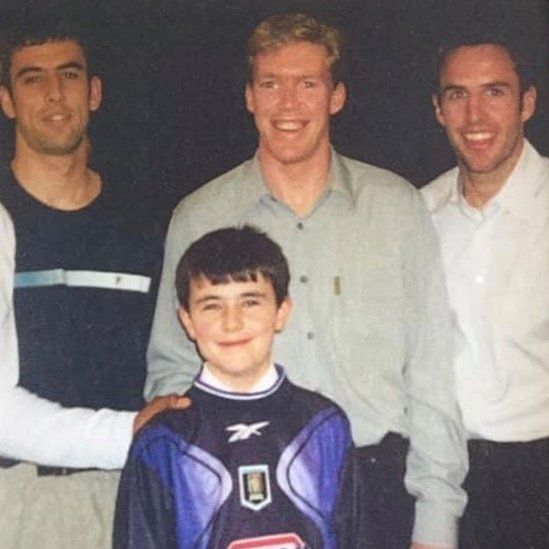

A young Chris meeting Aston Villa players - including Gareth Southgate

His day job is an assistant principal at a secondary school, where he says he uses his experience to encourage his pupils.

"I've done assemblies about... making the most of opportunities," says Mr Guerin, who got married in the summer. "It doesn't have to be quizzing or academic things, but whatever you've got some sort of an interest in, it's a really enjoyable thing to do."

Arran Fernandez, 27, was another gifted child - and says he also did not face any extra pressure.

He was just 15 when he went to Cambridge University to study mathematics, becoming the youngest Cambridge student since 1773. By the age of 18, he was the university's champion mathematician, known as senior wrangler.

Mr Fernandez - who was home-educated in Surrey - says: "My [university] experience certainly wasn't typical, but I also don't feel like I missed out. Every experience is unique in its own way.

"Socially I've never cared much about comparing my age with others, so I didn't feel different from my peers due to my age. Starting at university for the first time is a life change and a new experience for everyone, whether at 15 or at 18."

Arran was tutored at home by his father Dr Neil Fernandez

Mr Fernandez, who is now an associate professor of mathematics at Eastern Mediterranean University in northern Cyprus, says he always tried to perform as well as he could in his work - but "that's for my own satisfaction rather than external pressure".

"I found that people generally had high expectations of me, thinking I must be a 'genius' because of my age, but I didn't let strangers' perceptions or expectations affect my psychology or put undue pressure on me."

But he says he dislikes the term "child genius".

"I wasn't - and am not - a genius, just someone who was given exceptional educational opportunities and was able to make the best of them."

He says the opportunities and support he had do not make him "better" than anyone else - if anything they have inspired him to "pay it forward and try to support others to achieve similar opportunities and successes", he says.

Of course, being gifted as a child doesn't mean you have it all your own way all the time.

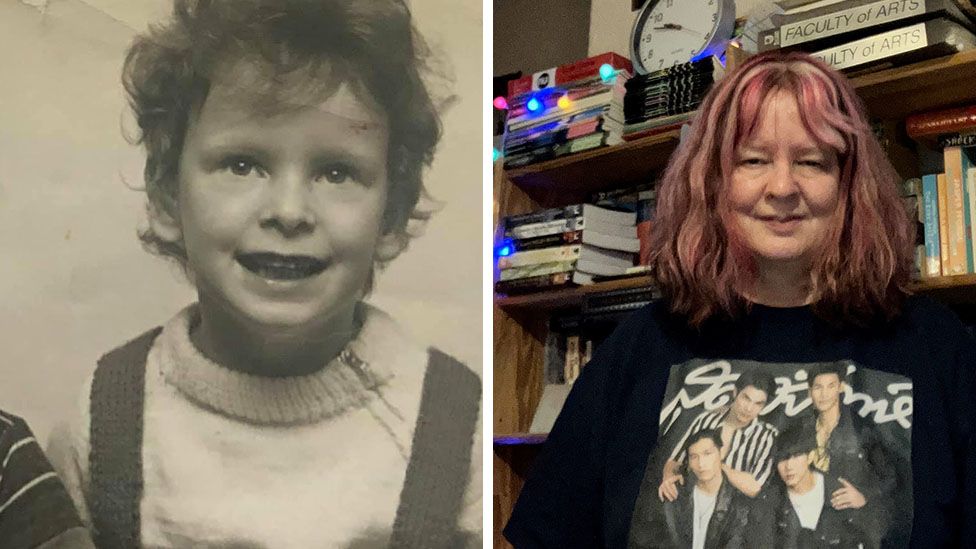

Jocelyn Lavin, who grew up musically talented and was accepted into the prestigious Chetham's School of Music in Manchester, says being a considered a child genius did not affect her negatively while growing up.

But she adds that in adult work life, people often want things done a certain way - "and they don't like when you don't fit the mould and have your own way of thinking and seeing things".

Jocelyn Lavin as a child and now as an adult

She has worked as a teacher and secretary among other jobs, and a few weeks ago she applied for her "perfect role".

"So I filled out their questionnaire on the application and emphasised that I felt I could do the job well with my researching skills and being able to find things out.

"However, they responded that my answers to their questions on the form were the opposite of what they were looking for in the role, which made me feel like the skills I have are holding me back in the job search."

Those of us who weren't child geniuses needn't worry - Wendy Berliner, an education journalist, says that often for adults who go on to be exceptional, "it is more to do with character, things like determination, drive, curiosity".

"Support is also very important - with people who go on to be high achievers you will usually find there is someone very supportive in the background who encourages them," she says.

Parenting a Mensa child can be 'exhausting'

Mensa's gifted child consultant, Lyn Kendall, says one thing she notices about Mensa children is how driven they are - they have a "need" to learn, she says.

She says Mensa runs a support group for parents of gifted children that currently has around 300 families. Being a parent of a Mensa child is demanding, she says. "It's exhausting, it's frustrating, it nearly ruins marriages."

Watch: Four year old boy joins Mensa, counts to 100 in six non-native languages

Journalist Ms Berliner says that anyone who thinks they have a gifted child should avoid "treating children as something which makes us as parents look good".

Instead, "encourage them as people that you just want to be comfortable and happy in their lives, that's the most important thing", she says.

And plenty of parents might be in that very position right now.

After four-year-old Teddy made the news for his high IQ, Ms Kendall says she received 38 emails from parents of three or four-year-olds.

They were asking for help and telling her: "We've got one like that."

What is Mensa?

Mensa counts 140,000 people around the world as members - including 18,000 in the UK and the Irish Republic.

The organisation describes itself as "the world's leading high IQ society", and says it provides its members with a space for like-minds to socialise, stretch themselves intellectually and engage in interesting activities.