The Bizarre Relationship of a ‘Work Wife’ and a ‘Work Husband’

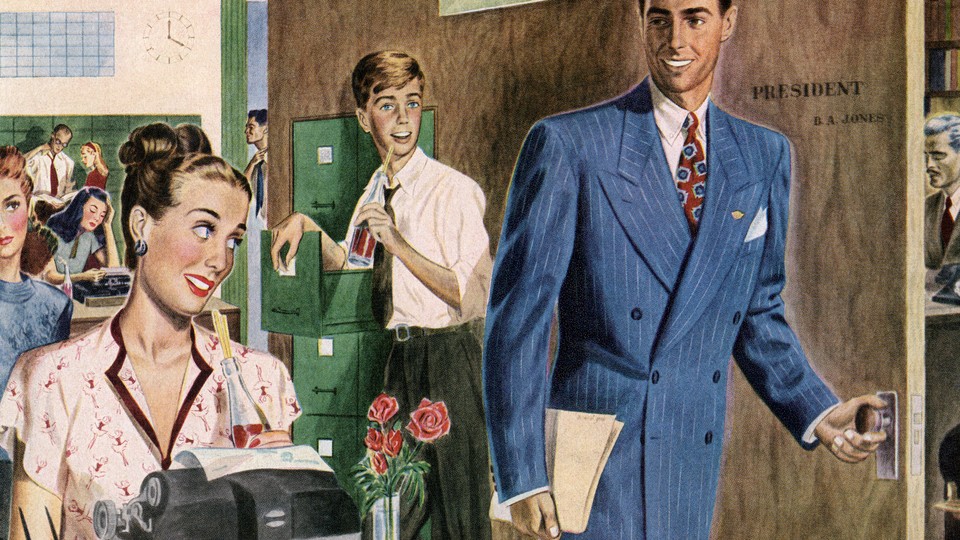

The work marriage is a strange response to our anxieties about mixed-gender friendships, heightened by the norms of a professional environment.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

It started out as a fairly typical office friendship: You ate lunch together and joked around during breaks. Maybe you bonded over a shared affinity for escape rooms (or board games or birding or some other slightly weird hobby). Over time, you became fluent in the nuances of each other’s workplace beefs. By now, you vent to each other so regularly that the routine frustrations of professional life have spawned a carousel of inside jokes that leavens the day-to-day. You chat about your lives outside work too. But a lot of times, you don’t have to talk at all; if you need to be rescued from a conversation with an overbearing co-worker, a pointed glance will do. You aren’t Jim and Pam, because there isn’t anything romantic between you, but you can kind of see why people might suspect there is.

The term for this type of collegial relationship—work wife or work husband—has become a feature of American offices. The meaning can be a bit slippery, but in 2015, the communications researchers M. Chad McBride and Karla Mason Bergen defined a “work spouse” relationship as “a special, platonic friendship with a work colleague characterized by a close emotional bond, high levels of disclosure and support, and mutual trust, honesty, loyalty, and respect.” Other scholars have argued that the connection actually sits somewhere between friendship and romance. Although articulating exactly what makes work spouses unique can be hard, individuals who have them insist that they are singular, Marilyn Whitman, a professor at the University of Alabama’s business school who studies the phenomenon, told me. But the language people use to describe this bond is even trickier to explain than the nature of the relationship: Why would two people who aren’t married or even interested in dating call each other “husband” and “wife”?

Read: Corporate buzzwords are how workers pretend to be adults

The term made a little more sense in its original form. The phrase office wife seems to have been coined in the second half of the 19th century, when the former U.K. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone used it to describe the oneness of mind and uncalculating commitment shared by a minister and his (male) secretary. In later decades, the expression became a means of referring to secretaries more generally—that is, to typically female assistants who handled their boss’s tedious affairs at work as his wife did at home. At times, it gestured toward the potential for romance, as in Faith Baldwin’s 1929 novel The Office Wife, in which a wife, a husband, and a secretary are entangled in a web of infidelity. But eventually, this trope fell out of favor; secretaries distanced themselves from the role of their boss’s caregiver, and the influential feminist scholar Rosabeth Moss Kanter criticized the gendered divisions of labor and power imbalances that work marriages created.

But work spouses didn’t so much disappear as evolve. By the late 1980s, in step with changing attitudes toward marriage, the dynamic had started to morph into something more egalitarian. As David Owen, a former contributing editor at The Atlantic, described in a 1987 essay, the new office marriage did not have to be a hierarchical and questionably romantic relationship between a boss and a secretary; it could be a platonic bond between a male and a female peer. The appeal, to Owen, lay as much in what the other person didn’t know about you as what they did: The two of you could share secrets about your real partners, but because your work wife didn’t know about your habit of leaving dirty dishes in the sink, she wouldn’t nag you about it. It was a cross-sex relationship that benefited from professional boundaries, offering some of the emotional intimacy of marriage without the trouble of sharing a household.

Today, your work spouse doesn’t need to be someone of the opposite gender, though McBride and Bergen found that these relationships still tend to occur with someone of the gender you are attracted to. You don’t have to have a real spouse to have a work spouse, though a lot of work spouses do. The office marriage has shed many of the stereotypes that once defined it, but the term itself has strangely persisted.

The impulse to assign some sort of name to a relationship like this makes sense. Labels such as “sister” and “colleague” give people both inside and outside a bond a framework for understanding it. Less traditional pairs, such as work spouses, “have to work even harder to justify and explain to other people who they are and who they are to each other,” Aimee Miller-Ott, a communication professor at Illinois State University, told me. Familial terms are common labels to choose—they’re universally understood and offer a “handy” set of metaphors, the anthropologist Janet Carsten explains. Usually, however, when people reach for kinship vocabulary to describe nontraditional relationships, they select blood relations, Dwight Read, an emeritus professor of anthropology at UCLA, told me. With the exception of some straight women calling their best friend “wifey,” using husband or wife is virtually unheard of—certainly within cross-sex friendships. None of the researchers I spoke with could think of another example.

Read: The widespread suspicion of opposite-sex friendships

This curious usage might simply be an artifact of the romance-novel “office wife” trope, Whitman suggested. But the marital language also makes some intuitive sense. Work marriages involve a type of compatibility, lastingness, and exclusivity that also tends to characterize real marriages. Of course, a lot of these traits are true of good friendships too. But when people hear the word friend, they don’t necessarily imagine this intensity—the word has been diluted in the age of Facebook, referring to any number of loose acquaintances. This is certainly true at work, where chumminess can raise eyebrows and friendliness itself is kept in check for the sake of professionalism. Against this backdrop, real friendship stands out. Add in the age-old misgivings about close ties between men and women, and the extended proximity that working together necessitates, and it’s unsurprising that people in a professional setting might assume that a tight bond is actually a disguise for the beginnings of a romance. Because of this, some avoid using the term work spouse publicly. For others, Miller-Ott suspects that combining the word work with wife or husband may be an expedient, if counterintuitive, way of addressing such suspicions: Yes, we’re very close. No, we’re not dating. Using a phrase that implies monogamy may help explain the relationship by affirming that it is atypical—that these two people have mutually decided to relax the rules of professionalism with each other but not with anyone else.

Employing the term in this way only sort of works, because although wife and husband reliably connote intimacy and singularity, they also imply sex and romance. Indeed, Carsten, the anthropologist, was somewhat amused that spousal language might be used to defuse rumors that two people are dating. One cannot borrow some implications of a word and leave the rest—and people seem to be aware of this. In Miller-Ott’s research, many of the people she spoke with called each other “husband” and “wife” only when they were alone. Others with close work friendships refused to use the label at all, Whitman and Mandeville found, fearing that their real partner might object.

But for some people, the slightly illicit connotations of the work-marriage terminology may be part of its draw. Perhaps that’s one reason so many colleagues who wouldn’t call each other “husband” or “wife” publicly continue to do so privately: Referring to someone by a title that skirts the boundaries of propriety may be a way to bond with them. But ultimately, work spouse breaks down for the very reason it works: It co-opts the exclusivity of a word intended to describe a very different relationship.