From the 1880s through the 1950s, white carnival-goers would throw baseballs, eggs, and other objects at the heads of Black men in a game known as "African Dodger."

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions and/or images of violent, disturbing, or otherwise potentially distressing events.

The Digital Resource Library of Illinois History Journal Riverview Amusement Park in Chicago, Illinois.

The carnival is in many ways a hallmark of American culture, a symbol of summertime entertainment and simple amusements: games, ferris wheels, funnel cakes, and corn dogs. Of course, like many things taken for granted, carnivals weren’t always innocent events.

Take, for example, the freakshow, which now serves primarily as fodder for horror movies but once was a very real horror for the people who were dubbed “freaks” and put on display for people to mock.

Performing animals didn’t fair any better, often subjected to cruel and inhumane treatment for the sake of entertainment — and for those who weren’t white, carnivals were often a public display of racist mockery more than anything else.

And in one particularly dark period in carnival history, target games with names like “The African Dodger” encouraged players — often children — to either literally or symbolically harm Black people for fun and prizes.

African Dodger, The Carnival Game Where People Threw Baseballs At Black Men

The game of African Dodger was perhaps one of the most brutal mainstream carnival activities to prominently feature racist vitriol — and “African Dodger” was one of the least offensive names for it, with other names sometimes blatantly featuring racial slurs.

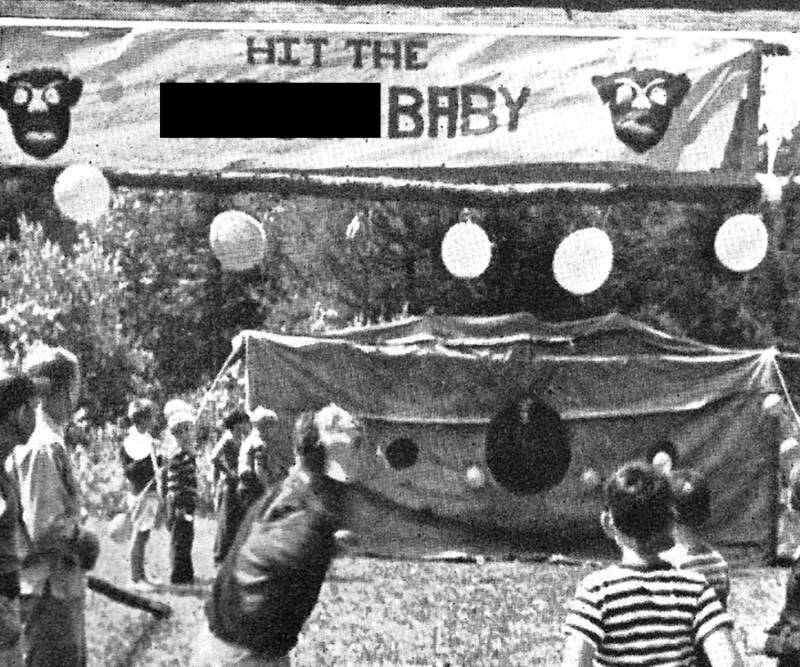

FacebookA racist carnival game featuring the words, “Hit The N***** Baby.”

The game had a simple premise: Throw something at a target, hit it, and win a prize. Except in this game, the target was a human. Carnivals employed Black men to stand behind a backdrop with their heads exposed to take the hits.

Carnival patrons paid money for a certain number of projectiles — sometimes rocks, other times eggs, but baseballs were a popular choice.

As you can imagine, the men suffered numerous horrible injuries from the “game.” Below are just a few reports archived by the Jim Crow Museum. As a warning, these accounts are difficult to read.

In 1904, the Meriden Daily Journal reported that one Black carnival employee named Albert Johnson worked as a dodger, and avoided “fifty or sixty cents” worth of balls thrown at him by a man named “Cannon Ball” Gillen of the Clifton Athletic Club — a professional baseball player. However, one of Gillen’s balls finally struck Johnson, and the damage was so severe that the Journal wrote it would “probably be necessary to amputate the nose in order to save Johnson’s life.”

Elsewhere, in Connecticut, a Black man named Walter Smith was struck so hard in the face that several of his teeth were knocked out. Reportedly, the baseball was lodged so tightly in his mouth that it had to be cut apart for removal.

In Hanover, Pennsylvania, William White was assaulted by a team of baseball players who brought their own heavy balls and hit him nearly every time. A reporter at the time noted that White “was pretty well used-up” by the end of it. White suffered a number of internal injuries that could have been fatal.

On Sept. 11, 1924, an advertisement in the Providence News asked the question, “Do you want to earn a few precious dollars on the evening of September 19 and 20?” The ad goes on to encourage “lion-hearted and hard-headed” young men to apply for a job as a dodger, with the promise that they would be treated fairly and “reach the Rhode Island Hospital safely in the event that that [sic] one of the baseballs comes in contact with your head.”

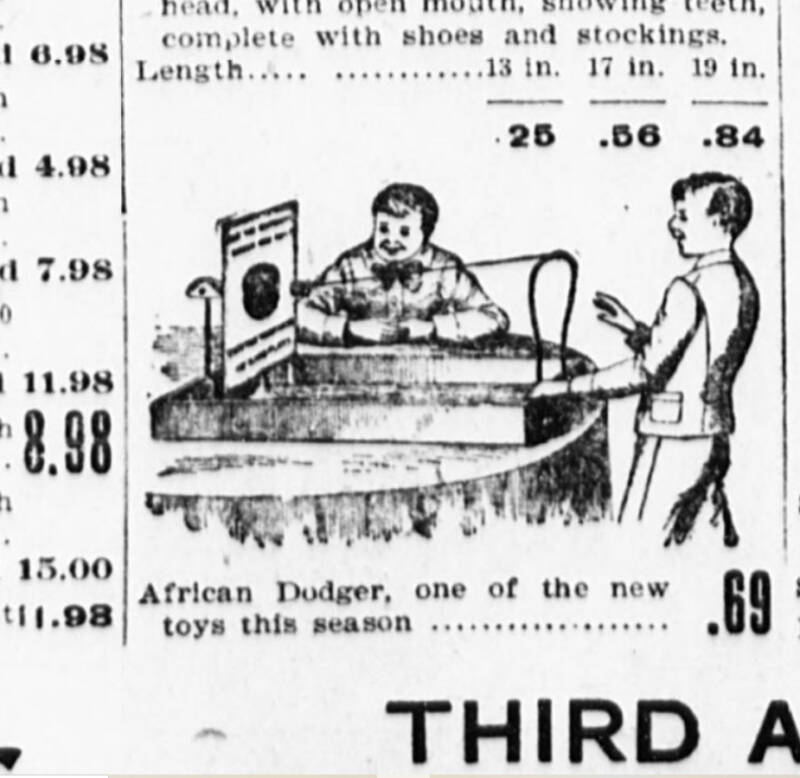

Library of CongressA 1893 ad for the at-home version of African Dodger.

The ad even mentions that the week prior, “an African dodger was killed in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and the week before a dodger was killed in Hackensack, but don’t permit these deaths to influence you.”

Clearly, carnival owners knew the risks of the game, but they didn’t care enough about the lives of their Black employees to put an end to it. On top of that, cartoons, advertisements, and signs often portrayed the dodgers as smiling, implying that they were more than happy to suffer the pain.

And for only $.69, those who couldn’t make it to the fair — or those who were particularly fond of African Dodger — could buy the at-home version of the game. This version also featured a smiling Black man and the words, “Hit the Dodger! Knock Him Out!”

The African Dip, A “Friendlier Alternative”

Even with the popularity of “African Dodger,” there was pushback from those who thought it was in poor taste. Popular Mechanics printed in 1910 that the “African dodger” was “too old and commonplace”.

However, not everyone liked the idea of banning African Dodger. The Washington Herald called it “depressing news.” The Trenton True American blamed the “progressive era” for the change in the beloved game.

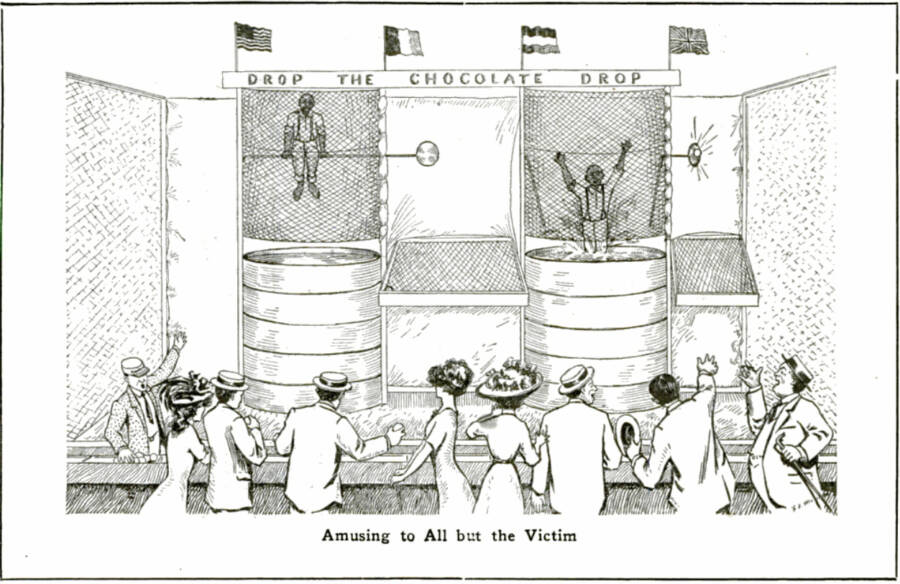

Popular Mechanics, Nov 1910.The accompanying illustration in Popular Mechanics shows a version of African Dip called “Drop the Chocolate Drop,” and calls it “Amusing to All but the Victim.”

Instead of banning African Dodger, organizers (begrudgingly) came up with a somewhat less physically dangerous game: the African Dip.

What was the African Dip? In short, it was a dunk tank that closely resembles dunk tank games still played today. Except in African Dip, white people lined up to throw balls at a target and drop Black people into the water.

African Dodger didn’t go completely extinct yet, though. In fact, people played versions of the original well into the 1950s. Instead of real people, some carnivals opted to use wooden targets that featured racist caricatures of African Americans as targets.

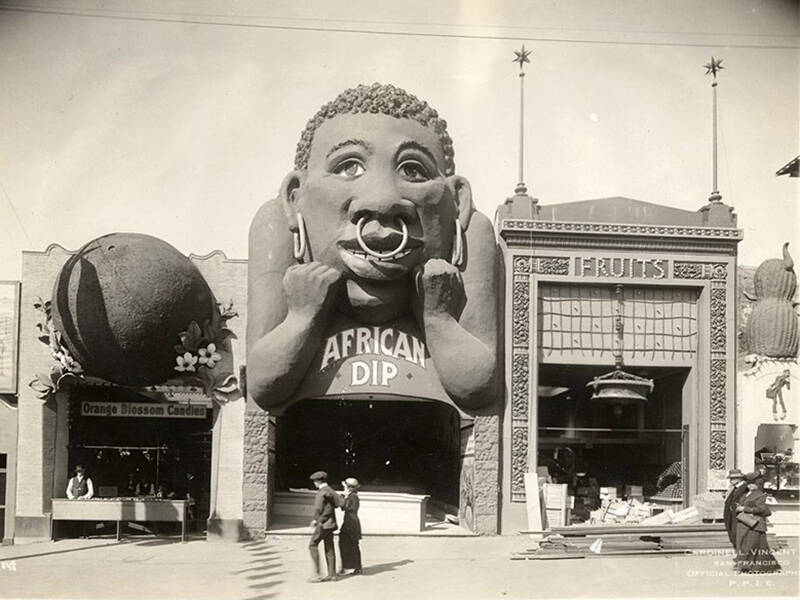

For example, Riverview Amusement Park in Chicago still had African Dodger as a main attraction until the late 1950s. And according to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal, the African Dip ran there until 1964, when it was shut down after the city’s civil rights protests.

The Impact Of Racist Carnival Games On Culture And Society

While some who played African Dodger and the African Dip may have dismissed them as “fun and games,” normalizing activities like African Dodger had a massive cultural impact.

A version of African Dip is still played today. In this more recent iteration of the dunk tank game, carnival-goers throw objects at a target to dunk a volunteer or a clown hired by the carnival, rather than a Black man.

Here, the roles are often reversed, with the clown hurling insults at passersby or taunting players rather than the humiliation being focused solely on the person in the tank. But even this practice is gradually falling into disuse as clowns retire and patrons lose their taste for public humiliation, the New York Times reports.

Racism goes deep, even into the company’s we would never think of. Donald Duck was going to play ‘African Dodger’ a game where you throw baseballs at a black man or baby. pic.twitter.com/iyWf0q8Ysd

— Dove🕊🅳 (@dove1k) July 5, 2020

While some may be inclined to disregard games like African Dodger as products of their time, that time only ended about 70 years ago — meaning there are people alive today who “played” African Dodger. And echoes of the racist sentiment that allowed games like African Dodger to exist for so long persist today.

As the Washington Post reported, Florida law enforcement officers were using the mugshots of Black people for target practice — an activity not all that different from African Dodger — as recently as 2015.

San Francisco Public LibraryThe African Dip at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

And though America has certainly made some strides in the fight for civil rights since carnivals staged violent games like African Dodger, it’s disheartening to think that there ever was a time where this sort of behavior was not just commonplace, but encouraged.

Next, read about Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the fearless Black activist who fought for women’s suffrage. Then, find out about the racist origins of America’s suburbs.