What shall we keep a keen eye out for at our next expedition to the flea market? Tramp Art! No I haven’t just insulted you, I’m talking about the little-known and often misunderstood branch of outsider art; curiously whittled wood works intricately carved from discarded cigar boxes – that’s right, cigar boxes. This humble and charming craft flourished in the second half of the 19th century in Europe and America until it became a lost art around the same time as the Great Depression and the outbreak of World War II. It was an art of the people, made by working class men, women and sometimes even children, across a diverse range of ethnic groups. The artists, the majority of which will likely remain forgotten, were factory workers, farmers, soldiers, builders, bakers. Tramp art seemed to thrive wherever scrap wood was readily available and manual labor was a required skill, not to mention, a great deal of patience.

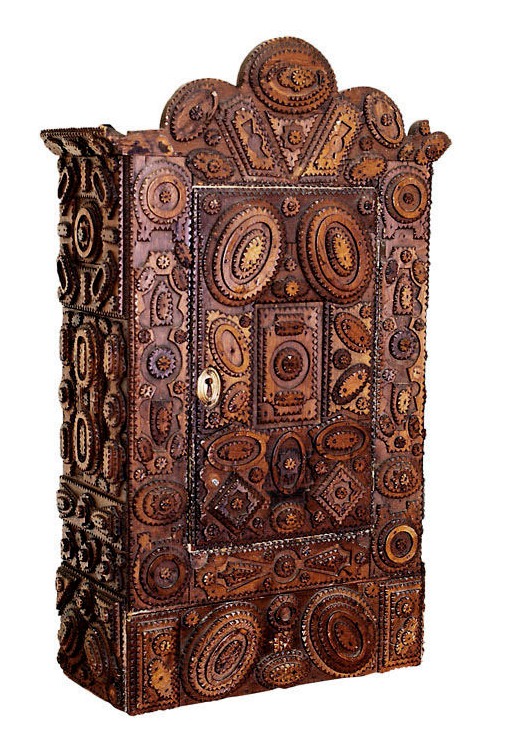

In keeping with the rules of Outsider Art, there were no rules in Tramp Art. Artisans used pocket knives to carve anything from picture frames to boxes to sizeable pieces of furniture. But one thing all these pieces have in common is geometry. The layers of geometric patterns carved into each creation is astounding. Such minute detail and precision, made by hand with the simplest of tools. The technique has been called “Crown of Thorns” because of its resemblance to the prickly wreath widely depicted in the crucifixion of Christ.

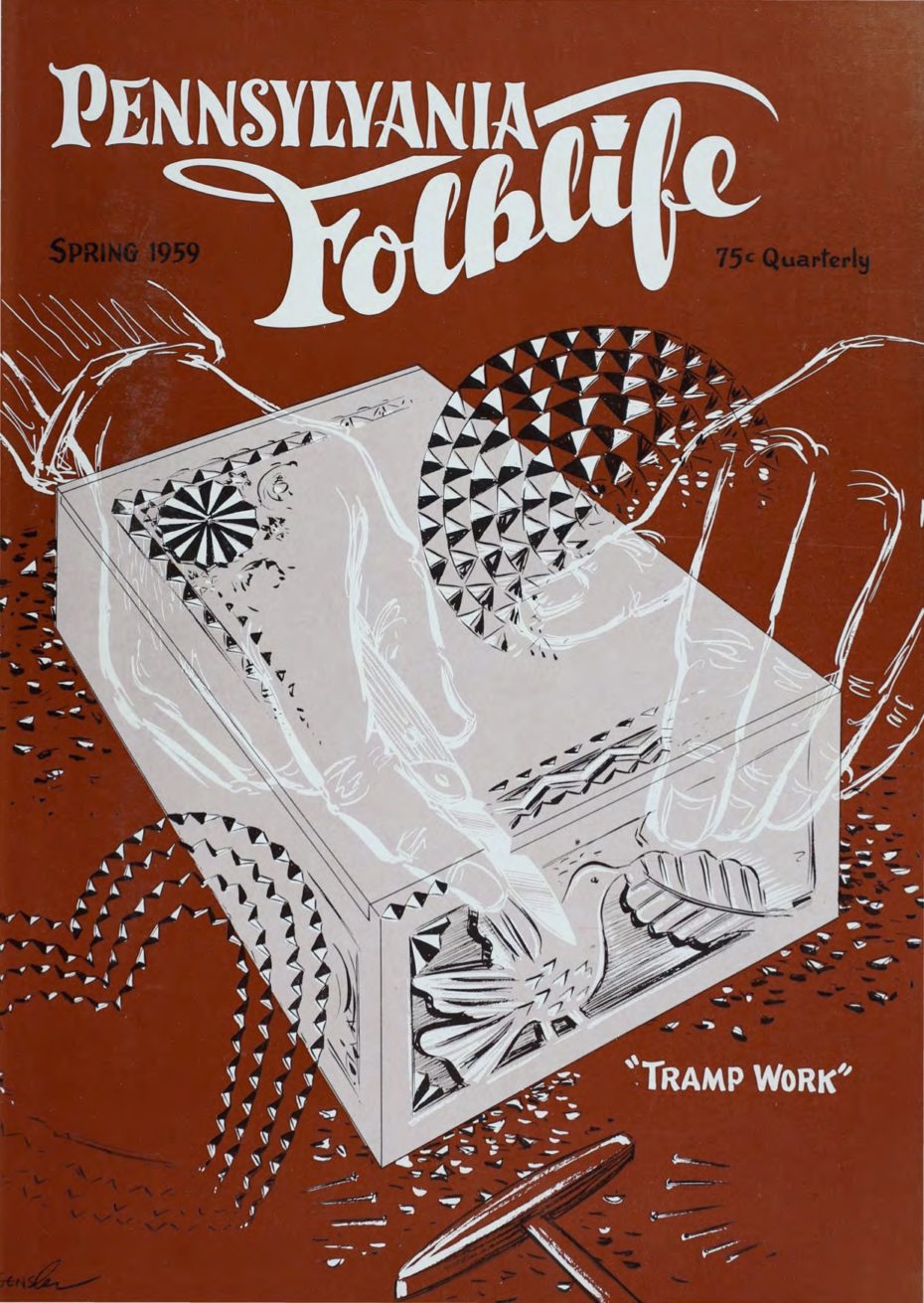

So what’s with the unfortunate name: “Tramp Art”? Both unfortunate and largely inaccurate, the name leads to the assumption that we’re looking at the art of a homeless vagabond, which is rarely the case. The term came into the wider public consciousness in 1959 when it was mentioned for the first time in writing and referenced as an art form some two decades after Tramp Art’s popularity had already waned.

In a Spring issue of the Pennsylvania Folk Life quarterly magazine, author Francis Lichten titled her article “Tramp Work: Penknife plus Cigar boxes.”

Even if the author herself believed the term was unflattering and had borrowed it from the parlance of vintage dealers and pickers, the name stuck.

A research associate in the Decorative Arts department of the Philadelphia, Lichten describes how she first discovered a carved wooden object she identified as “Edged carve work”, gathering dust and destined to be burned for firewood in Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouse (you can read the full article here). Francis Lichten had just rescued what would become one of the most prominent examples of this particular vernacular movement.

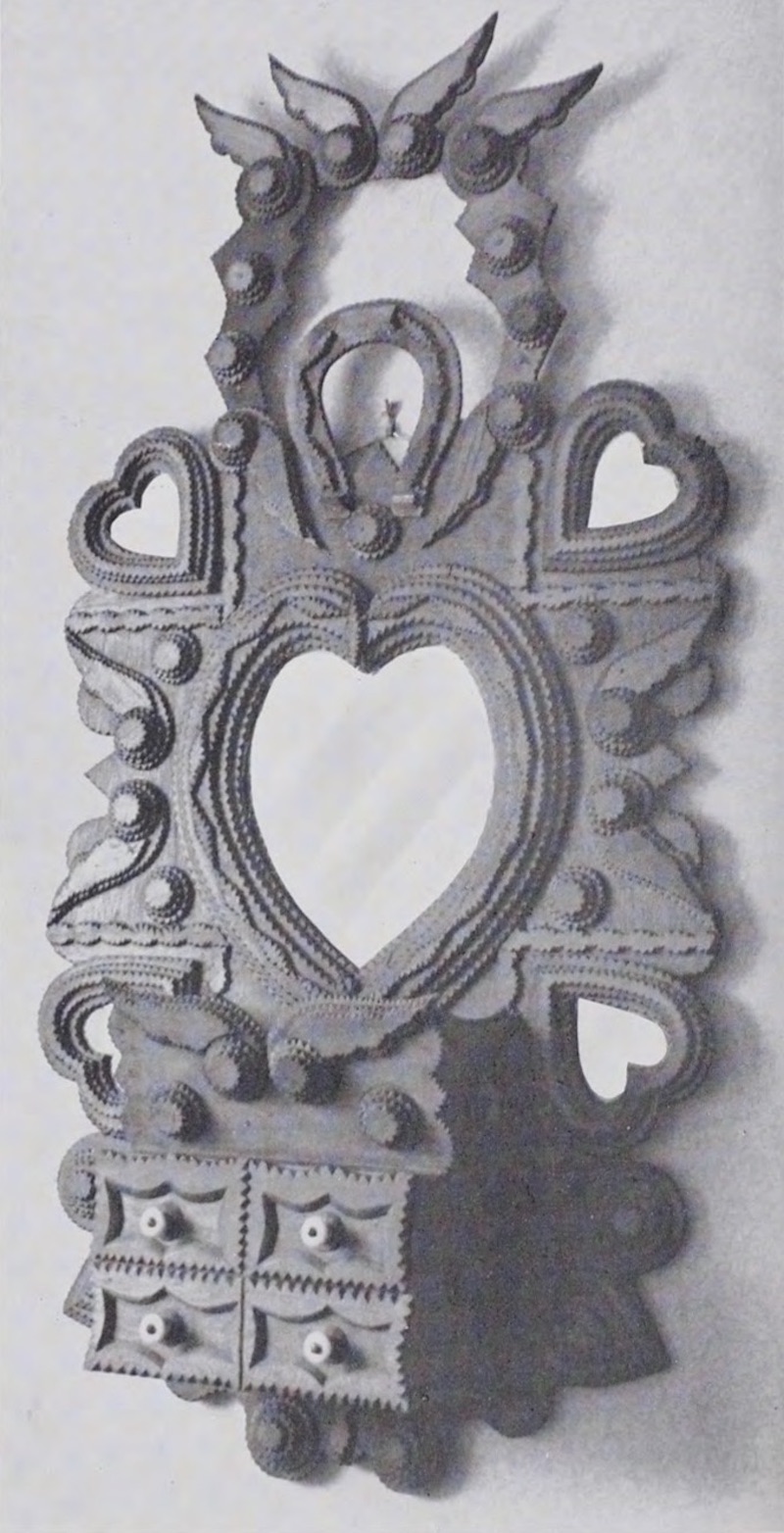

There are only a handful of notable names in the realm of Tramp Art, including one John Martin Zubersky of Illinois (active c. 1912 – 1920) known for his “sunflower” frames and John Zadzora of North Hampton, PA (active circa 1910), known for his romantic “wall pockets”. While the majority of Tramp Art was created by ordinary folks who might have made one or two pieces over their lifetime, John Zadzora created many, and it was only thanks to an “odd quirk” on the back of his hanging dressing cabinets that they were able to be attributed to him some 50 years after he made them. What Francis Lichten had discovered in that Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouse, was the work of John Zadzora.

He is first identified in the 1959 magazine article she wrote, where it’s revealed that his wall pocket, commonly hung in kitchens in Pennsylvania Dutch communities, was in fact created while he was imprisoned at the Lehigh County Jail (for reasons lost to history). Talk about finding a way to pass the time.

Lichten goes on to speculate about the “average Joe” behind the art and how they might have created it.

“The craft of edge carving was one which lent itself to sociability as it could be followed wherever the whittling fraternity congregated– in such well-known centers of good talk as benches outside the country store, in the dim corners of livery stable or black-smith shop, or around the stove.”

The closest Lichten comes to suggesting any connection to an actual “tramp” or some kind of vagabond character is here: “edge carving was practiced by elderly German immigrants whom the machine age had passed by. Whatever their craft may have been, there was no longer any demand for it. But … they still liked to keep busy, so turned to the making of small wooden objects which they could peddle throughout the countryside, or exchange for a night’s lodging and a meal or two”.

While our craftsmen were also known to use the occasional discarded shipping crate, you might be wondering: why cigar boxes?

“Cigar boxes were plentiful at the turn of the century, as men smoked cigars, not cigarettes… [they] provided just the kind of wood the carvers preferred for their work…” writes Lichten in 1959, whose father coincidentally owned a cigar factory when she was a child, which may have contributed to a nostalgic connection with the art. In any case, it seems fitting that Francis Lichten, who is no longer with us, would be the one to introduce it to the world.

Being so far from the world of high art and its masters, Tramp Art was very poorly documented during its height of popularity from the 1870s to the 1940s. Author and collector Clifford Wallach is one of the few experts in Tramp Art and has a website dedicated to the genre, answering many of the questions a potential collector might want to know.

Based on his 29 years of collecting, he has some basic advice for buying Tramp Art. A few tips I found particularly useful:

- Buy what you like.

- Buy pieces in the best possible condition.

- Study the books available to get an idea of the breadth of the form and what appeals to you.

- Ask questions before buying. Find out what is known about the piece so you can preserve any background or histories associated with the object.

- Do not clean pieces with any solvents or cleaning products.

- We use white Elmer’s glue to secure pieces that have fallen off.

- Some collectors specialize in specific forms such as boxes, frames, painted objects, or whatever appeals to you.

- Be careful of reproductions. Buy from reputable dealers with a guarantee of authenticity for life.

Now about those reproductions. How can we know what’s authentic? Firstly, Wallach recommends doing your homework with the few books available on the subject. He is the author of two, Tramp Art: One Notch at a Time (1998) and Tramp Art: Another Notch, Folk Art From the Heart (2009).

Cigar box stamps can often be found under the drawers of Tramp Art cabinets or on the back of frames. Those stamps can sometimes reveal the the date and origin of the material, roughly indicating when and where the piece was made, but the truth is, its still a mystery as to where Tramp Art first came from. Some of the finest examples predate what we’ll call “the golden age” of American Tramp Art and countries in Europe like Switzerland and Germany have a rich history of woodworking tradition and skilled woodcarvers.

While Francis Lichten guessed that most of the American Tramp Art was made in Dutch Pennsylvania, with its abundance of immigrant German artisans and communities where “the craft traditions lingered on”, Wallach thinks the art may have flourished wherever men smoked cigars. And if that’s the case, you might find examples of Tramp Art anywhere around the world where there was a constant supply of cigar boxes lying around for the everyday artisan carrying a penknife.

So look up your local flea markets if you live anywhere near an old cigar-manufacturing town. And if you happen to be antique hunting in the eastern Pennsylvania area, it would be worth keeping a keen collector’s eye out at the Blue Ridge Flea Market or the Philly Flea.

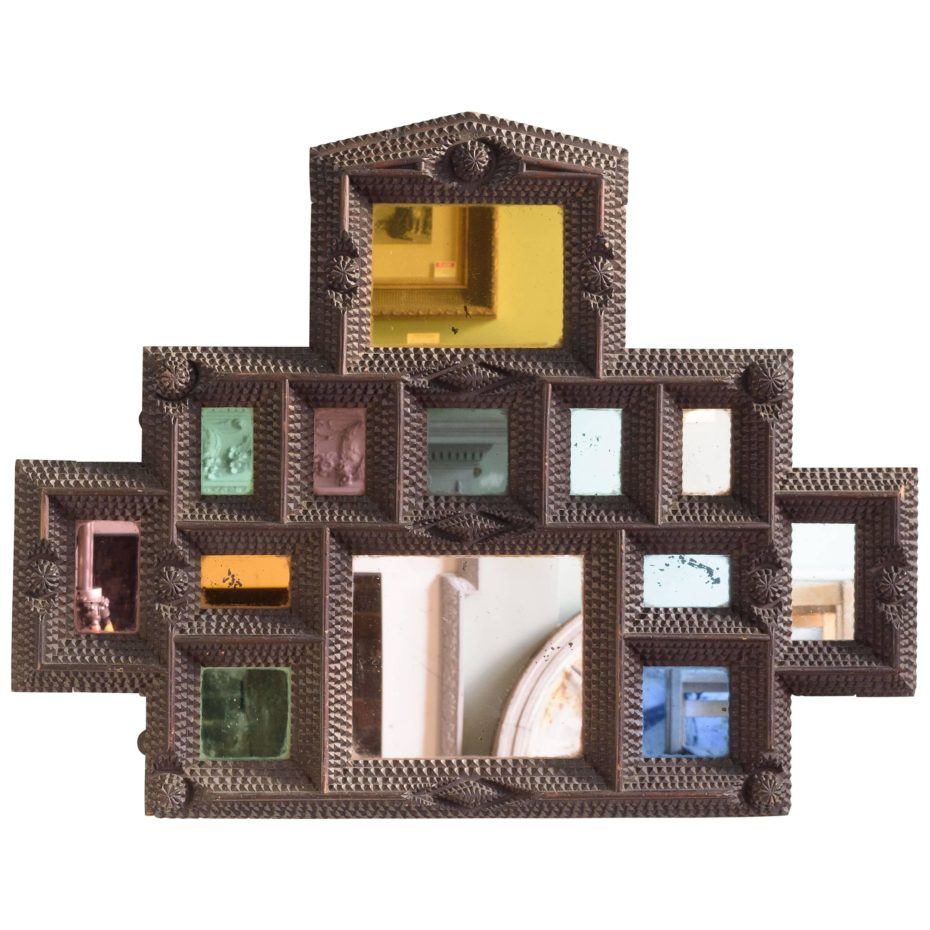

What’s most exciting about collecting Tramp Art is that it’s a relatively new discovery, meaning that not everyone knows its worth – yet. Prices are still affordable if you know where to look and what to look for, but don’t sleep on it. A quick Google search shows that a pair of early 20th century chip-carved mirrors went for just under $7,000 at Christie’s. You can get a better idea of flea market prices on eBay.

I think what I like most about Tramp Art, aside from it being strangely beautiful, is the part where you get to fill in the blanks about the unknown maker and imagine them whittling away the time with just a cigar box and a penknife.

“I find them touching examples of the craftsman’s losing fight against industrialism which wiped out the craft tradition in a few decades,” wrote Francis Lichten in her 159 article, a sentiment I can also relate to in my own way sixty years after she first wrote about Tramp Art.

Being of a technology-dependent generation, where our free moments are so often consumed by a reflex to scroll through social media, I find Tramp Art endlessly inspiring. I wonder if surrounding ourselves with it wouldn’t serve as a helpful reminder to create something beautiful with those “in between” moments in life.