When the soldiers came, Cathay Williams’ life changed forever. It was June 1861, and Williams was an enslaved 17-year-old woman living near Jefferson City, Missouri. That month, still in the early stages of the American Civil War, Union troops took over the city. Missouri would become important in that conflict, a slave state that remained loyal to the United States, but with a population split in their allegiances.

The Union troops did not free Williams or the other enslaved people on the Johnson plantation near Jefferson City. Instead, United States troops took her and other enslaved people with them as they moved south to battle the Confederate forces. Williams was not free: She was legally “contraband,” enemy property that the United States now controlled. Traveling with the U.S. Army was not her choice in 1861, but it became her new life. In the years that followed, Williams supported the United States troops as a cook and then a washerwoman. In her travels, she witnessed several important battles.

The Civil War ended in April 1865, and the 13th Amendment freed all enslaved Americans by December. Newly freed people like Cathay Williams began to imagine what their lives might become in the war’s aftermath.

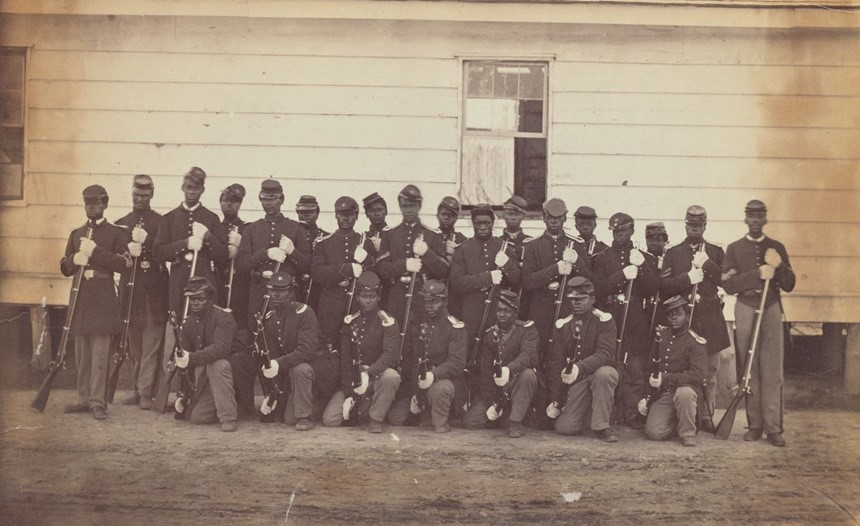

Less than a year later, Williams chose to return to military service — this time, on her own terms. The war had ended, but the U.S. military still needed soldiers, both for reconstruction in the southern states, and out west in the territories Americans continued to settle. To support these goals, in 1866 Congress established six regiments for African American troops. African Americans had served the U.S. Army near the end of the Civil War, but this was the first time that Congress planned to use Black soldiers on a large scale. They became known as Buffalo Soldiers in the years that followed, serving primarily in the western territories and states.

Cathay Williams was the first and only woman Buffalo soldier, although no one knew that when she enlisted. None of the military services allowed women in their ranks in the 1800s, although several women, disguised as men, had served in the American Revolutionary War and the Civil War. Dressed as a man, Williams signed on to the 38th Colored Infantry Regiment. While recruiters assessed her fitness to serve, they did not perform a physical examination that might reveal her gender.

Only two people close to Williams knew the truth that the new recruit everyone called “William Cathay” was actually a woman. These men, also in the 38th, never told anyone William Cathay’s true identity. According to Williams, these two men were an important reason why she enlisted. One was her cousin, and one was “a particular friend,” she said, although she never explained exactly why their influence led her to the Army.

But Williams also believed military service offered her significant opportunity. In the Army, she could make her own money. At approximately $13 a month, it wasn’t necessarily a large amount of money, but Black soldiers earned the same amount as white soldiers. In the Army, soldiers also received lodging and food. Military service offered Williams more opportunities than she would have had as a Black freed woman in Missouri or any other state at the time. She signed up for a three-year term, but caught smallpox just after enlisting and remained in St. Louis while the 38th moved west. Williams caught up with Company A, her assigned unit of 75 soldiers, at Fort Riley in Kansas. Company A continued on to New Mexico, ultimately landing in Fort Cummings.

From 1867 to 1868 in New Mexico, no one ever caught on to the fact that William Cathay was a woman doing everything all the other soldiers did. All that changed in 1868, two years into her service. That January, Company A was assigned to its first winter mission, a week-long march to attack an Apache village. The attack never happened, but the experience was nonetheless consequential to members of the 38th Infantry. The Buffalo soldiers had not been given the proper clothing to survive the low temperatures and winter weather, and rations were low. Many members of the 38th became sick in the months that followed.

Private William Cathay became sick at the end of January 1868. She was treated briefly, then returned to duty for the next two months. In late March, the same thing happened — she fell ill, received treatment, and returned to duty. Williams and her Company transferred to Fort Bayard in southwest New Mexico territory. Still, she struggled with her health. On July 13, Williams became a patient at the Fort Bayard infirmary. Through these hospitalizations, her identity as a woman was either never discovered, or was, perhaps, carefully overlooked.

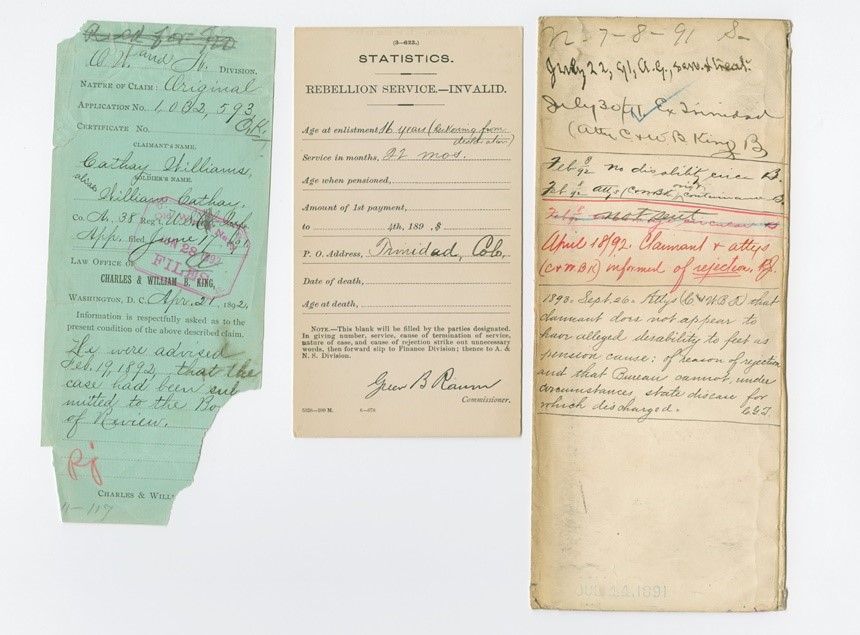

That fall, however, Williams’ masquerade ended. The surgeon at Fort Bayard revealed that Cathay was a woman, and in October the assistant surgeon signed a certificate of disability for William Cathay. This document discharged William Cathay from the Army. The men of her company, Williams reported, wanted nothing to do with her once the truth was revealed.

In 1876, Cathay Williams’ story was published in the St. Louis Daily Times under the title “She Fought Nobly.” The reporter encountered her while on a visit to Trinidad, Colorado, where Williams lived at the time, running a business doing laundry and sewing. There, she had made a new life for herself. A decade and a half later, in 1891, the U.S. government denied her claims for a disabled veteran’s pension.

Cathay Williams was the first in a long, distinguished history of Black American servicewomen. During World War I, the Golden 14 became the first Black women of the U.S. Navy. In World War II, the soldiers of the 6888th were the first and only Black women to serve overseas. In 1948, the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act passed just weeks before President Truman desegregated the military, opening even greater opportunities for women in the decades ahead.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now