“I remember thinking that if you’re involved in this, you need to accept the possibility that at the end of the day, you may have to kill people.” Rose Dugdale, then 70 years old, was huddled in a high-backed leather chair, hands folded in her lap, when she made this remark in a rare interview for a 2012 documentary series. With short gray hair and a red sweatshirt engulfing her small frame, Dugdale bore little resemblance to the independence fighter of her youth. “I tried to wrestle with that thought and dealt with it,” the English heiress-turned-militant recalled. “There can come a time when you may or may not want to kill people, but at the end of the day, it’s the only way to deal with them.”

Despite Dugdale’s willingness to kill for the cause of Irish independence from British rule, no lives were taken on January 24, 1974, when she and three accomplices hijacked a helicopter and dropped two makeshift bombs on a police station in Strabane, Northern Ireland. The amateurish explosives—packed into a pair of milk churns—failed to detonate. Dugdale’s next grand act in support of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) would be something more suited to her posh English background: art theft.

What led this University of Oxford-educated woman to stray from a life of comfort and privilege to militancy and a disdain for wealth? She was born Bridget Rose Dugdale in March 1941, to a father who was an underwriter for the insurance market Lloyd’s of London and a mother who was an heiress herself. Dugdale’s childhood involved horseback riding at Yarty, her family’s Devon estate, and attending the same finishing school as singer and actress Jane Birkin.

Mná an IRA - Episode 1

The turning point of Dugdale’s life was the debutante season of 1958, when she was one of 1,400 young women presented to Elizabeth II. (1958 was the last time this nearly 180-year-old tradition took place.) Dugdale found the festivities overindulgent and a waste of money, later saying, “It was as if you were being sold as a commodity. I didn’t enjoy it at all and really wanted to get out of it.” She cashed in her ticket to a new life by convincing her father to fund her education at Oxford the next year in exchange for her participation in the season’s events.

The 1960s saw Dugdale diverge from her parents politically, as she became wrapped up in the revolutionary spirit that had swept college campuses worldwide. Full of idealistic energy and imbued with a deep disdain for wealth and those who held onto it, she threw herself at the first worthy cause that crossed her path.

Dugdale’s activism began in the working-class town of Tottenham in North London in 1971, “a really difficult time in Britain and Ireland,” says Robert J. Savage, a historian at Boston College. “The government there is in crisis. Inflation is high, unemployment is high, there’s tremendous labor unrest. … The government was actually forced to create a three-day workweek because people couldn’t keep the lights on.” Now in her 30s, Dugdale was well off the path once envisioned by her parents, and she made quick work of exhausting her inheritance. She handed out heaps of money to poor, largely immigrant families trying to make rent and heat their homes for the winter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/ae/3caee39a-e564-4396-bebd-85fe5b1cdd54/gettyimages-2098854757.jpg)

But everything changed on January 30, 1972, when British soldiers fired on demonstrators in Derry, Northern Ireland, killing 13 unarmed civilians and injuring at least 15 others. Known as Bloody Sunday, the deadly attack proved to be a turning point in the Troubles, a sectarian conflict that devastated Northern Ireland between the late 1960s and the late 1990s.

“It’s a time when there’s an incredible amount of violence,” says Savage. Some left-leaning Brits grew convinced that they should support the IRA, which they believed was fighting “a war against an imperialist power.” As Dugdale explained in the documentary, after Bloody Sunday, “there was no question that you needed to do everything you could to support that cause, to free the Irish people.”

Dugdale funneled her remaining funds into firearms for the IRA, which she and her boyfriend Walter Heaton then ferried into Northern Ireland. When her inheritance ran dry, Dugdale turned to the only source she knew of to procure more funds: her parents. With Heaton, she embarked on her first art crime, stealing about £82,000 worth of art and silver (around $1 million today) from her family’s Yarty estate in June 1973.

The couple’s crime was quickly discovered, and they stood trial that October. Heaton was sentenced to six years in prison, while Dugdale received a two-year suspended sentence, as the judge deemed the chances that she would ever commit such a crime again remote.

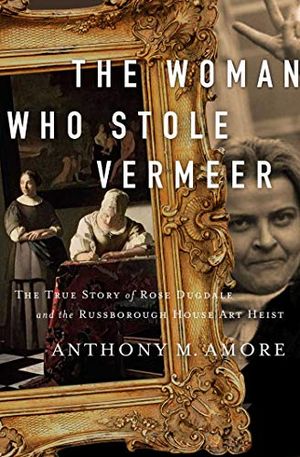

Anthony Amore, an art theft expert and the author of The Woman Who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist, says, “She was way ahead of her time—so far ahead of her time that no one would believe her. You have a judge say, ‘You’re unlikely to offend again, and surely you’re under the sway of this man.’”

By the spring of 1974, Dugdale had moved on to a new relationship with Eddie Gallagher, a member of the IRA’s paramilitary force, the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Alongside two other accomplices, Dugdale and Gallagher had recently carried out the botched bombing at Strabane, and they were now on the run. Laying low, Dugdale was busy planning what would become her most notorious act yet.

Her new target was Russborough House, the lavish County Wicklow, Ireland, home of Sir Alfred Lane Beit and his wife, Lady Clementine Beit. The Beits represented everything Dugdale despised: They were wealthy members of the British aristocracy, and their ancestral fortune had roots in the South African gold and diamond mining industry. The fact that the Beits had lived in South Africa and were vocally anti-apartheid didn’t stop Dugdale from targeting the treasure trove of fine art that adorned the walls of their mansion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/34/8034248f-4f89-41da-a4c3-c7ba20bd7964/gettyimages-833523486.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/95/2b/952b40cb-89aa-4457-9146-64c70114b509/clementine.jpg)

Shortly after 9 p.m. on April 26, 1974, the Beits were listening to music in the library, oblivious to the doorbell ringing at the staff entrance. Servant James Horrigan greeted a woman with a thick French accent, who began complaining of car trouble. Suddenly, three masked men carrying assault rifles barged into the house behind Dugdale, who was disguised in a wig.

The four thieves made quick work of the Beits and their staff, tying the prisoners up in the library before taking Clementine down to the basement. Alfred made the mistake of looking up at one point, only to be struck on the head with the butt of a gun. Over the next ten minutes, Dugdale made her way around the estate, pointing out the most prized paintings to her companions and occasionally yelling “capitalist pig!” at Alfred.

The crew departed Russborough House with 19 works of art valued at an estimated £8 million (around $110 million today), including paintings by Francisco Goya, Peter Paul Rubens and Diego Velázquez. One of the stolen works, Woman Writing a Letter, With Her Maid, was one of just two Johannes Vermeer paintings under private ownership at the time. Dugdale and Gallagher hid with the paintings at a seaside cottage she’d rented in County Cork; the other two thieves fled elsewhere.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/80/8f801e69-056f-4cf4-9968-31a2c23c00c2/woman_writing_a_letter_with_her_maid_by_johannes_vermeer.jpeg)

One week after the heist, Gallagher left to secure a new hiding spot for the plunder. En route, he delivered a ransom note stating that the paintings would be returned in exchange for the transfer of four IRA members from a prison in England to one in Northern Ireland, as well as a payment of £500,000. If the demands weren’t met, all 19 masterpieces would be destroyed on May 14.

Meanwhile, authorities were combing the area, and the IRA was denying association with the theft. Albert Price, father of two of the prisoners mentioned in the ransom note, called the still-unidentified criminals “robbers covering up with excuses” and asked that the art be returned. His daughters, Marian and Dolours Price, had been convicted of a 1973 bombing and were on a hunger strike in an English prison when the robbery took place. They, too, urged the thieves not to destroy the priceless art.

On May 4, the Irish police stopped at Dugdale’s cottage as part of a routine canvas. Unconvinced by her fake French accent, they raided the rental while she was out, discovering incriminating material related to the theft. When Dugdale returned, they arrested her. Out of options, she surrendered quietly. Authorities found three of the stolen paintings in the cottage and the rest in the trunk of a car Dugdale had borrowed from the rental’s landlord.

In court, Dugdale entered a plea of “proudly and incorruptibly guilty.” She refused to name her accomplices and was sentenced to nine years in prison. Around this time, she discovered that she was pregnant with Gallagher’s child. Dugdale gave birth to a son named Ruairí on December 12, 1974, while imprisoned in Limerick.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/75/9975673d-4ff8-4d31-a268-ffd26e424ba1/tiede_herrema_1975.jpeg)

Gallagher soon found himself on trial for an entirely different crime. In October 1975, he and fellow IRA member Marion Coyle kidnapped Dutch businessman Tiede Herrema in a failed attempt to ransom him for Dugdale and two other IRA prisoners. Herrema survived his 36 days in captivity unscathed; Gallagher was sentenced to 20 years in prison, Coyle to 15.

Dugdale and Gallagher made headlines again in 1978, when, after much petitioning, they became the first imprisoned couple to marry in the Republic of Ireland. Nevertheless, the pair grew estranged following Dugdale’s release from prison in 1980, after serving six years of her sentence.

Back on the outside, Dugdale moved with Ruairí to a cottage in the Coombe, a working-class Dublin neighborhood. Neighbors and friends often tended to Ruairí, while Dugdale wrote furiously for An Phoblacht, a newspaper published by the Irish republican political party Sinn Fein. She also helped drive the efforts of the IRA-backed group Concerned Parents Against Drugs, which sought to remove dealers from the streets during a heroin epidemic.

In 1985, Dugdale began a relationship with the married IRA bomb maker Jim Monaghan. The pair initially headed and taught courses for Sinn Fein’s education department but quickly turned to weapons development for the IRA. Their deadly innovations included empty bean cans converted into hand grenades, a homemade nitrobenzene replacement and a grenade launcher that used packets of digestive biscuits to minimize recoil. These weapons were used in attacks on West Belfast, a British army barracks in County Armagh and London’s Downing Street, where the IRA killed or injured dozens of police officers, government officials and innocent civilians.

As Dugdale continued her militant pursuits, an unsupervised Ruairí fell into the drug scene, selling ecstasy as a young man before emigrating to Germany in 1994 for a fresh start working in construction. “For [Dugdale], everything is the cause, and I think for her, whatever that cause might be, whatever path she decided to follow, would always take [precedence] over whatever personal relationship[s] she had in her life,” says Amore, the art theft expert.

Dugdale’s dedication to Irish independence led her to commit acts that landed her in prison. At the same time, it earned her the respect of Irish republicans who were initially skeptical of an English heiress. This grudging regard was evident last month, when Dugdale died in a Dublin nursing home at age 82. On March 27, a crowd of people clad in black bomber jackets and Easter Lilies gathered around the entrance to the Crematorium Chapel in Glasnevin, Ireland. From a black hearse, pallbearers wearing tricolor armbands carried a wicker casket holding Dugdale’s remains. Prominent IRA supporters, including Coyle and former Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams, came to say goodbye to their fellow revolutionary.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/85/c385d3c0-580a-45d2-9828-a101bc5db9b6/gettyimages-2110556848.jpg)

Fifty years after the art heist at Russborough House, Dugdale remains a divisive figure. “I always try to remember to tell people that she tried to commit a mass murder,” Amore says. “When they did that bombing that failed, if it had gone the way she planned, it would have been a slaughter of … innocent people.” But it’s also worth acknowledging the empathy Dugdale displayed toward the poor of Tottenham and believers in the Irish republican cause. Savage says, “She was a supporter of the peace process,” which brought three decades of unrest in Northern Ireland to a close in 1998. “She wasn’t a dissident in spite of the violence that she seemed to embrace.”

Dugdale’s characterization as a valiant freedom fighter or a violent criminal depends on whom you ask. “In Great Britain, people will see her as a terrorist,” says Savage. “Those that were victims of the IRA will see her as a terrorist and be appalled at the notion that she should be celebrated or embraced as a heroic character. But she, like others, will provoke admiration from some and … condemnation from others.” Ultimately, he concludes, “It’s a mixed legacy.”

For those who struggle to comprehend how an heiress could part with the advantages she was born into for a life of extreme, often militant advocacy, Amore is frank in his assessment, saying, “I think she was just wired differently than most people.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.