“If we can create portraits of subjects that are true, we thereby in effect create a mirror of the times.”

– August Sander, creator of Menschen des 20 Jahrhunderts (People of The 20th Century)

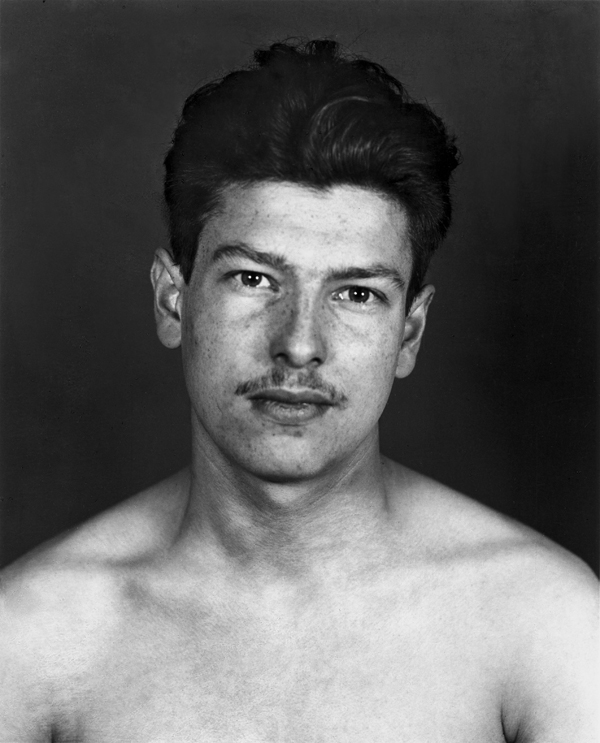

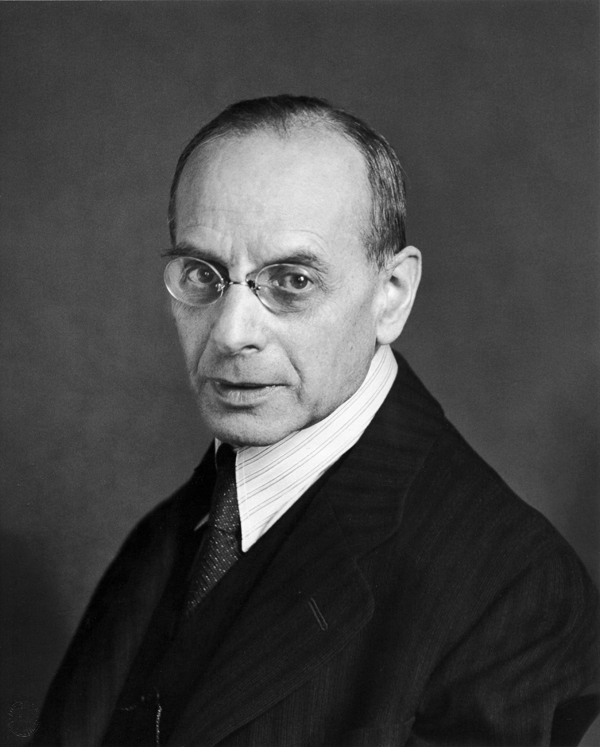

What you see above is a picture of Arnold Katz and Benjamin (Benno) Katz being paraded through Cologne during a boycott of Jewish businesses on 1 April 1933. This press photograph was seen by photographer August Sander (German, 1876 – 1964), who took pictures of Arnold for a series called The Persecuted that formed the penultimate volume of his posthumously published compendium People of the Twentieth Century.

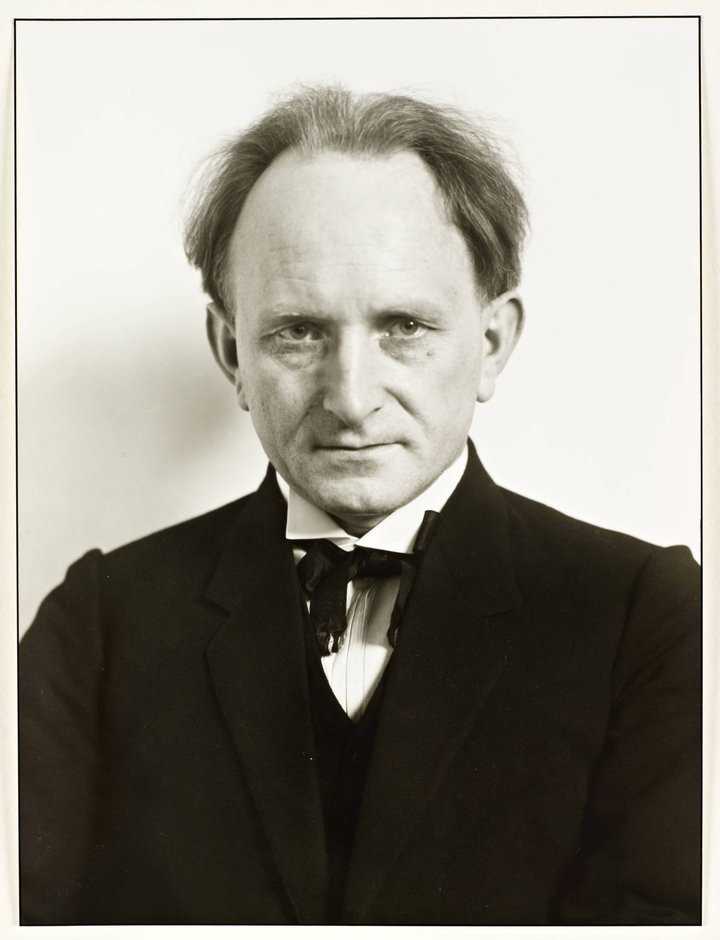

Katz and his son were not alone in being victims of the murderous persecution of Jews led by the Nazis and taken up with gusto by many people in countries throughout Europe and Asia. Sander took other portraits of Jews ensnared in the anti-Semitic campaign.

Dear Benno…

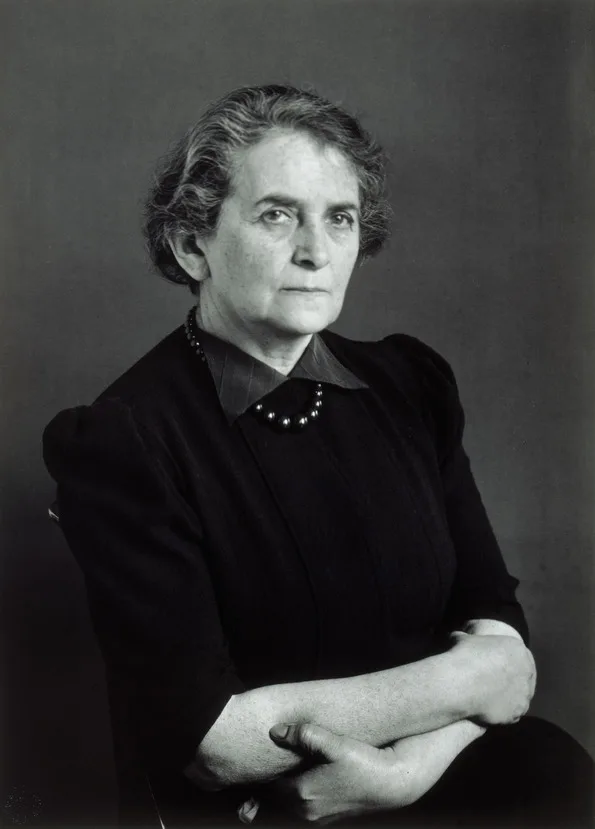

![August Sander, Persecuted [Adele Katz], ca. 1938](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/August-Sander-Persecuted-Adele-Katz-ca.-1938.jpg)

August Sander, Persecuted [Adele Katz], ca. 1938

We know what happened to Benno Katz because the Nazis and their cohorts documented their demonic crimes.

In December 1941, Benno’s daughter, Adele Katz, sent a postcard from the Litzmannstadt ghetto in the Polish city of Łódźt. It was never received. In it she said:

“My two dears, first of all let me send you my very best wishes. I’m sorry to say that so far we have waited in vain for news from you.”

Arnold and Benno were butchers and meat wholesalers in Cologne. The family opened the business in 1892 not far from August Sander’s home and studio. But on April 1, 1933, the day of Germany’s first nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses, Benno and Arnold were forced to march the streets of Cologne carrying defamatory, anti-Semitic signs.

Eventually, Benno and Adele were sent to the Łódź ghetto. By May 1942, just months after Adele wrote her postcard from Łódź, she and Benno were deported to the Chemno extermination camp and murdered.

![August Sander, Persecuted [Mrs. Franken], ca. 1938](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/August-Sander-Persecuted-Mrs.-Franken-ca.-1938.jpg)

August Sander, Persecuted [Mrs. Franken], ca. 1938

We cannot be certain why Sander took portraits of Cologne’s Jews. Some argue that he was an antifascist and his pictures helped German Jews obtain exit papers. He was certainly not a Nazi. Sander and his wife, Anna (1878-1957), shopped in Jewish-owned stores when to do so carried grave risks. And he’d been on the receiving end of Nazi barbarism when the fascists destroyed many of his pictures in 1934 and imprisoned his eldest son Eric for antifascist activities.

Erich, who died in prison in 1944, became a prison photographer, and several of his own portraits of political prisoners were integrated into his father’s work.

August Sander, VI:44a:7 Political Prisoner Portfolio VI:44a—The City, Political Prisoners, 1943

Whatever the reason for his taking pictures of Jews, Sander thought documenting different human types according to their roles in German society would produce an unsentimental snapshot of the time and place. It would be a comprehensive pictorial cultural history and social analysis. His work would record the whole of German society, including both Nazis and those they persecuted.

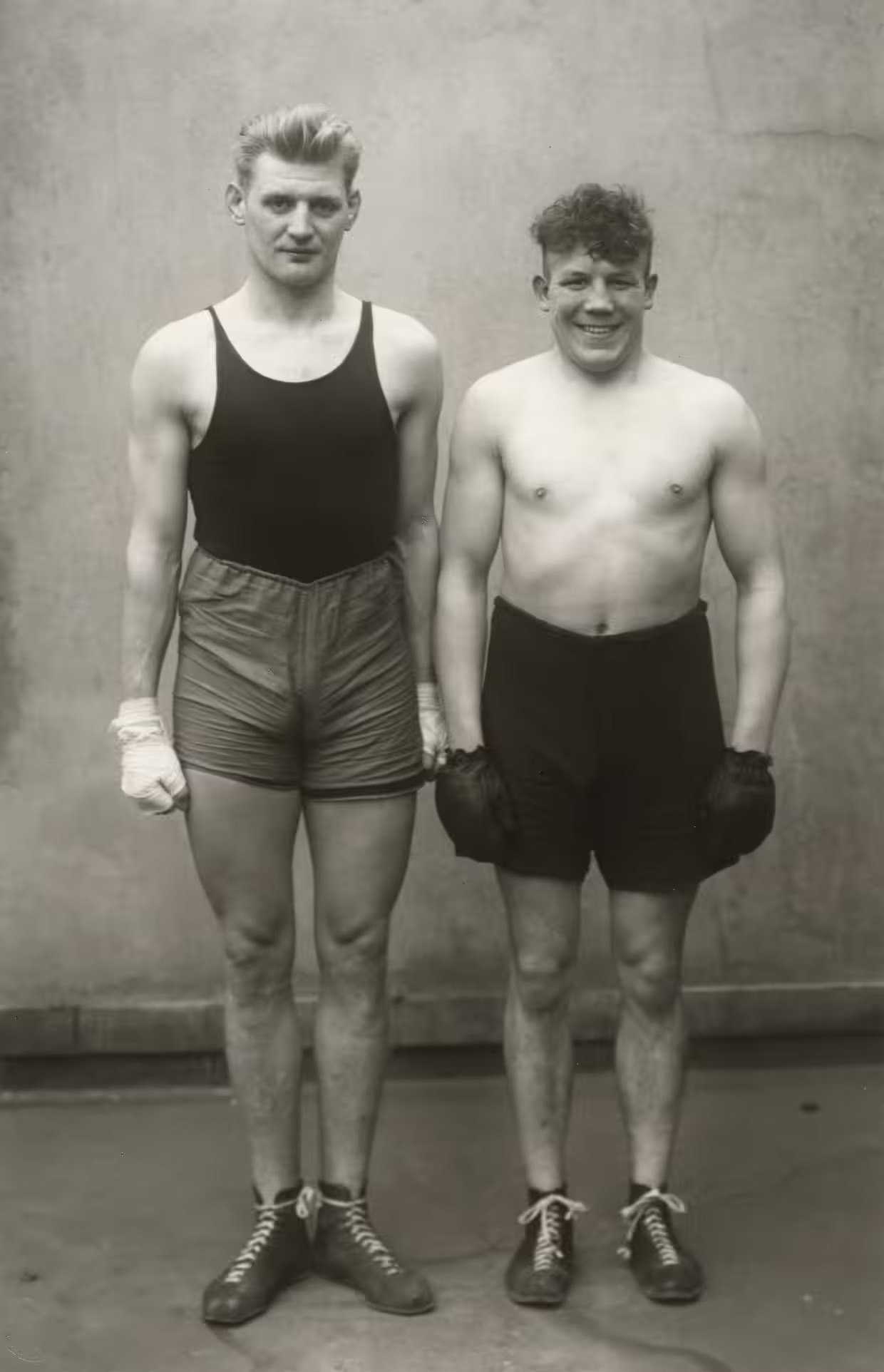

So he took realistic portraits of the philosopher, the revolutionary, the sage, the worker, the young farmer, the country girls, the pastry cook, the working students, the National Socialist, the tycoon, the boxers (below) and so on.

Sander named his project “People of the Twentieth Century”.

It includes over 600 photographs divided into seven volumes organised as: The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City and The Last People.

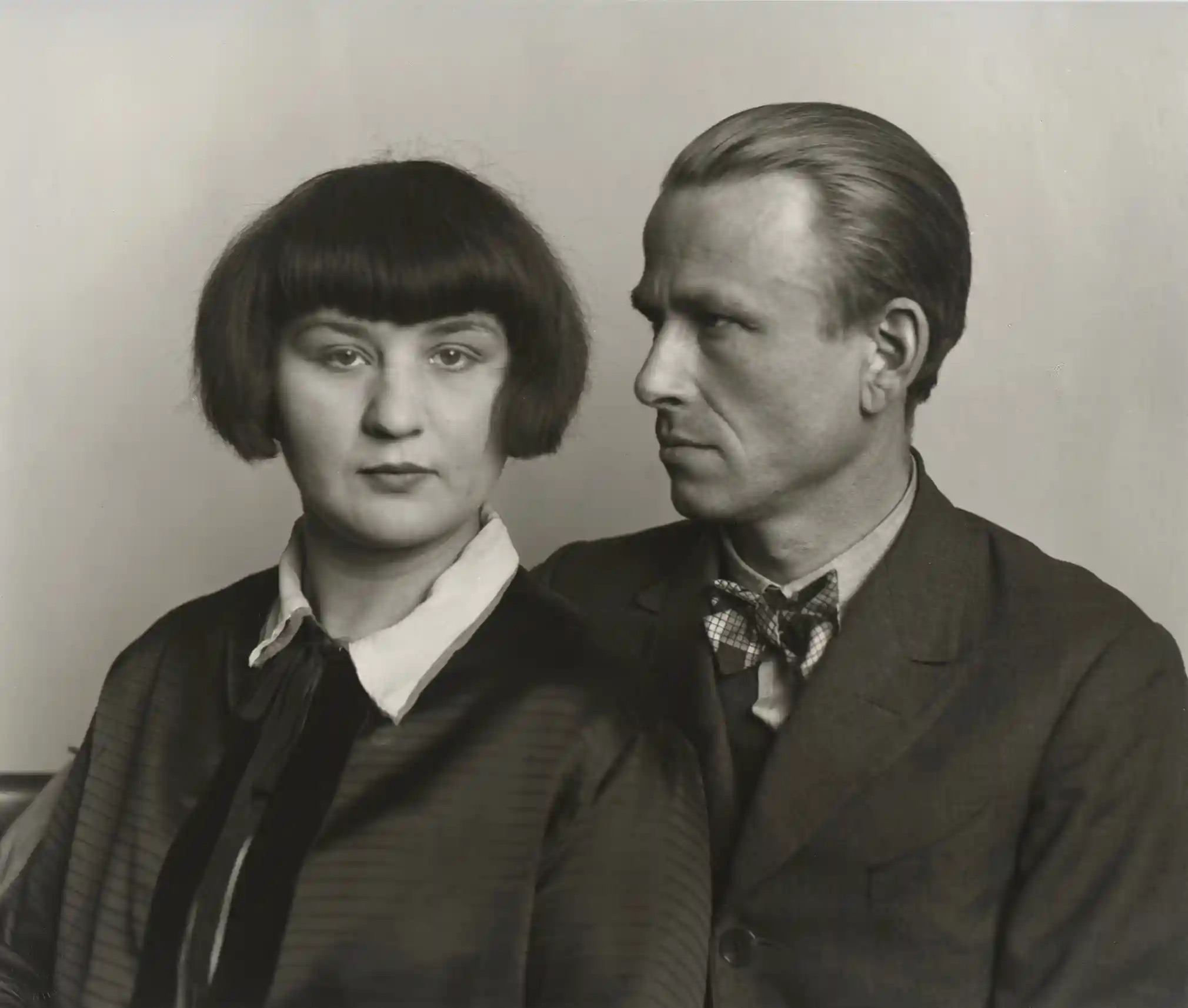

The Painter Otto Dix and his Wife Martha, 1925-26

Physiognomy & Photography

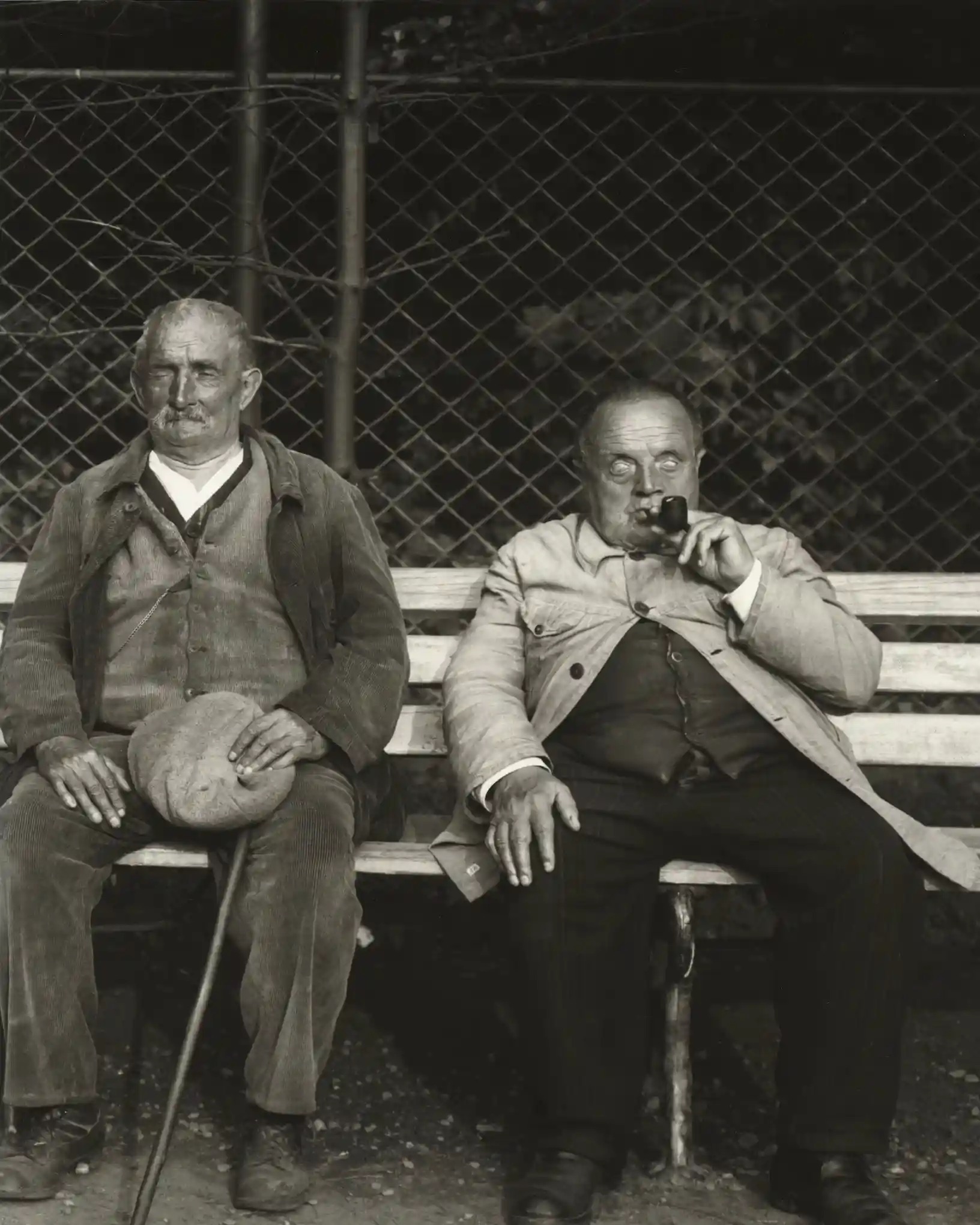

Blind Miner and Blind Soldier, c. 1930

Many see Sander’s work as supportive of physiognomy, a theory that seeks to form a systematic link between psychological characteristics and facial features or body structure.

For those who believed in it, physiognomy was a tool for discriminating character by the outward appearance and as a method of divination from form and feature. Popular in the 19th century, it was used to justify racial profiling, discrimination and the Holocaust.

Farming Family, 1913-14

“The individual does not make the history of his time, but he both impresses himself on it and expresses its meaning,” Sander said. “It is possible to record the historical physiognomic image of a whole generation and – with enough knowledge of physiognomy – to make that image speak in photographs.”

As a practitioner of New Objectivity a movement led by his friend, the painter Otto Dix, with a goal of a return to realism, Sander wanted his photographs to expose truths. “Pure photography allows us to create portraits which render their subjects with absolute truth,” he said. “If we can create portraits of subjects that are true, we thereby in effect create a mirror of the times.” He wanted to “honestly tell the truth about our age and people.”

The Persecuted

August Sander, VI:44:8 Persecuted Portfolio VI:44—The City, Persecuted, ca. 1938

The stories by the images of images of Jews are chilling.

Philipp Fleck, the editor of a bis z magazine, was deported and murdered in the Lódz ghetto in 1942. He never received the letter his brother, Richard Fleck, sent him in May of that year. “You can imagine how I long for some news of you,” Richard wrote. “I hope you are, at least, in good health.”

The Persecuted Jew – Mr Katz

“Last week I was again busy with Menschen des 20. Jahrunderts,” Sander wrote, in 1947, of his intention to include the persecuted in his portfolios. “We got the Jew folder down on paper. These are people who emigrated or breathed their last in the gas chambers. All magnificent heads of unpolitical people.”

The End

Sander’s inclusion of Jews and other marginal elements of German society incurred the disapproval of the National Socialist party. In 1936, the Nazis confiscated his first published version of the project, Face of Our Time (Antlitz der Zeit), and destroyed all the printing plates.

World War II forced Sander to leave Cologne in 1939. He took only what he considered his most valuable negatives. Around 1,800 negatives for People of the 20th Century have survived, as well as Sander’s notes and plans. The first publication of the work was confiscated by the Nazis and 40,000 negatives were destroyed in the bombing of his studio in 1944.

The Persecuted Jew

A decade after the war ended, Edward Steichen featured some of Sanders’ photographs for the exhibition “The Family of Man” at The Museum of Modern Art in 1955.

Despite the project spanning some 60 years, Sander still considered it unfinished and didn’t publish the completed book during his lifetime. His son Gunther worked on the archive and published the images under the title that August had originally planned, Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the Twentieth Century), in Munich in 1980.

August Sander died in Germany in 1964 at the age of eighty-seven.

Via: Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919–1933 at Tate Liverpool

August Sander: Persecuted/Persecutors, People of the 20th Century

Mémorial de la Shoah, the Holocaust museum in Paris.