Fifty years after the Civil War, the people of the defeated Confederacy raced around the country in a monument building frenzy. Their goal: memorialize the rebellion as a “Lost Cause” – a noble but doomed effort by the heroes of the South. Statues of Confederate leaders and memorials to veterans began cropping up all over the country in a bid to rewrite history. Slavery, as both an essential mechanism of the antebellum South and the main point of contention in the war, also needed to be cleaned up. According to those who embraced Lost Cause ideology, the Confederacy’s valiant young men would never have taken up arms to preserve an institution built on injustice and evil. However, they would sacrifice for a system which was for the good of all Southerners, black and white, and created “the strong bonds between the races” rooted in benevolence and fidelity.1

To make slavery palatable and refute “the assertion that the master was cruel to his slave,” the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) added the “faithful slave” to their list of people to memorialize in the early part of the 20th century.2 The UDC was (and still is) an organization “dedicated to the purpose of honoring the memory of its Confederate ancestors; collecting and preserving the material for a truthful history of the War Between the States; [and] recording the participation of Southern women in their patient endurance of hardship and patriotic devotion during and after the War Between the States.”3

What better representation of the faithful slave than the mammy, “she who, by her extraordinary devotion, her steadfast loyalty, helped to make the bitter aftermath of the war in the South endurable”?4 The UDC needed a monument to the mammies.

The Black Mammy is a caricature that any Southerner – or any American, really – will instantly recognize. She lives in children’s cartoons, where she waves a broom around at misbehaving animals. She shows up in romantic novels, where she looks after sweet young women until they get married. She even graces our breakfast tables in the form of a syrup bottle. She has a “large dark body and…round smiling face.” We know “her deeply sonorous and effortlessly soothing voice, her infinite patience, her raucous laugh, her self-deprecating wit.”5 Newspapers from a century ago, when the mammy character was first manufactured, call her a surrogate mother to her charges, a “’black foster-parent,’ who lived only for ‘dem white chillun’” who “never ceased loving. Her devotion grew with her own age and her charge.”6

The post-Civil War descriptions of this made-up woman don’t stop there and they become increasingly unflattering. One white writer from Houston, Texas described the ubiquitous mammy as “wholly unlearned, without even the rudiments of education, holding with unshakable belief to all manner of superstition, filled with terror and direful foreboding if the ‘squeech’ owl was heard even once at twilight…with hell fire and brimstone as essential ingredients of her religious belief…Her faith in God was the simple, trusting faith of childhood.”7

Many a Southerner in the late 19th and early 20th centuries looked back on their own “Mammy” with fondness and nostalgia. “His mind goes back to the tender embraces, the watchful eyes, the crooning melodies which lulled him to rest, the sweet old black face.”8 But those memories were, at best, viewed through rose-colored glasses and, at worst, pure fabrication.

The campaign to memorialize the “Faithful Colored Mammies of the South” began in 1910 in Galveston, Texas, where an organization of wealthy businessmen proposed to erect a monument to “Old Black Mammy.” Soon, they were flooded by “appeals from prominent men all over the country to make the movement…a national affair.”9 The idea transformed into building a “million dollar monument” – supporters would collect $1 donations from around the U.S., allowing as many people as possible to “mak[e] amends for a long-neglected duty in rearing a monument to our faithful slaves.”10

For one reason or another, the fervor over a mammy monument died out until 1923, when the Jefferson Davis Chapter of the UDC revived the proposal, now seeking approval to erect it in Washington, D.C., where it would help shape the national narrative around slavery. This time, they made it to Congress. Mississippi Senator John Sharp Williams brought the bill to the Senate in January 1923. In March, it passed and was sent over to the House.

Though the UDC seemed to be on the verge of getting their statue, the African American press was not going to let that happen without a fight. While some papers printed the news along with proposed designs, personal stories of readers’ mammies, and amateur poetry about the good old days in the South, others gave voice to the outrage and insult felt by the descendants of those misremembered women. Charlotte Hawkins Brown, the founder of a boarding school for African Americans and an active advocate for civil rights, suggested another method for remembering the “Mammy”: “If the fine spirited women, Daughters of the Confederacy, are desirous of perpetuating their gratitude, we implore them to make their memorial in the form of a foundation for the education and advancement of the Negro children descendants of those faithful souls they seem anxious to honor.”11

The Washington Eagle was a little more forceful in its disapproval: “A single bomb can remove a monument more rapidly than sculptors and builders can erect it.”12

Dozens of letters to the editor expressed the shared reactions of insult and anger that such a proposal would even be considered. Thomas H. R. Clarke wrote to the Afro-American, voicing his concerns. “The proposed monument is brought forward simply to remind intelligent and progressive colored men and women of the degradation of their mothers, an insidious insult to the race delivered under the guise of gratitude for the Negro blood the white South drew into its veins from the bosoms of helpless black women.”13

It was especially shocking in the wake of a failed anti-lynching bill which had been tossed out just before the Mammy monument was approved. “The Daughters of the Confederacy would do better if they made an effort to see to it that the sons and daughters of the so-called ‘mammies’ were not lynched and burned in the South and that their rights as citizens were respected.”14

Activist and founder of the National Association of Colored Women Mary Church Terrell led a charge against the statue as well. “Colored women all over the United States stand aghast at the idea of erecting a Black Mammy monument in the Capital of the United States. The condition of the slave woman was so pitiably, hopelessly helpless” – not cozy and familial as the UDC would have the monument imply.

The Black Mammy had no home life. In the very nature of the case she could have none. Legal marriage was impossible for her. If she went through a farce ceremony with a slave man, he could be sold away from her at any time, or she might be sold from him and be taken as a concubine by her master, his son, the overseer or any other white man on the place…The Black Mammy was often faithful in the service of her mistress’s children while her own heart bled over her own little babies who were deprived of their mother’s ministrations and tender care which the white children received.15

While she did not go so far as to suggest a bomb, Terrell also hoped that any statue which might be built would end up as rubble:

If the Black Mammy statue is ever erected, which the dear Lord forbid, there are thousands of colored men and women who will fervently pray that on some stormy night the lightning will strike it and the heavenly elements will send it crashing to the ground so that the descendants of Black Mammie [sic] will not forever be reminded of the anguish of heart and the physical suffering which their mothers and grandmothers of the race endured for nearly three hundred years.16

More letters of protest poured into senators’ offices and the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA even appealed to Vice President Calvin Coolidge and Speaker of the House Frederick H. Gillett to block the bill.

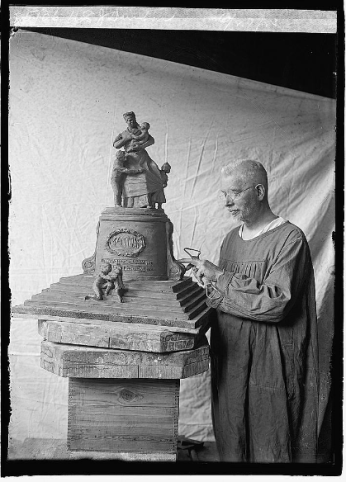

Meanwhile, white sculptors were squabbling over designs. Artist Ulric S. J. Dunbar was in a rage over what he claimed was a stolen concept. Sixteen years prior, he said, Tennessee Senator Robert Love Taylor had asked him to create a preliminary design for a similar monument which was never built. Now, George Julian Zolnay, the sculptor commissioned by the UDC for this and many other Confederate monuments, was presenting a similar idea, though his incorporated a fountain (a concept which Dunbar found ludicrous).17 Dunbar claimed that Zolnay had just “got to the newspapers” first. He found it strange “that Mr. Zolnay’s model should embody much of the symbolism which served as the inspiration for his model.”18 Never mind that they were working from the same concepts and narrative promoting Lost Cause ideology. Zolnay, though, refused to have this fight with Dunbar.

So what was this monument supposed to look like? Both designs showed a “mammy” holding a white child, smiling down at it, while her own children reached for the attention she withheld in favor of her master’s offspring. Dunbar’s was a statue and Zolnay’s a bas relief over a fountain. (“Bah,” said Dunbar. “He has a fountain in it. How could any one make a fountain symbolic of the black mammy?”19)

According to The Chicago Defender, the editor of that paper helped put the last nail in the coffin of the mammy monument bill. Congressman Morton D. Hull, a member of the Library Committee of Congress which had “charge of all matters relating to public monuments in the District of Columbia,” wrote to Editor Robert S. Abbott to ask his opinion on the matter. Abbott wrote back, “To us the Black Mammy is no heroine. She was an ignorant untaught servant, whose natural affections were traded upon, and who has been held up for generations to young ambitious and aspiring Colored men and women as an ideal for which they ought to strive.” He echoed other suggestions for a better monument to “Mammy”: “What Colored Americans want first is their rights and privileges and protection under the Constitution – the abolition of Jim Crow laws and lynching.”20

Hull evidently took his advice, replying that “In view of your statement it was the conclusion of the committee that it would be unwise to permit the erection of the statue to the Colored Mammy of the South.”21

In an ahistorical turn of events, African American protesters had won the day and Washington was saved the hatred and heartache of another racist monument.