The passive voice: despised by teachers, maligned by editors, and misunderstood by almost everyone. For over a century, this grammatical construction has been the bogeyman of English writing, blamed for everything from weak prose to political evasion. But here’s the kicker: Most people railing against it couldn’t spot a true passive if it tap-danced across their keyboard. So why has this humble verb form become public enemy number one in the world of grammar?

Active Voice vs. Passive Voice

Let’s start by clarifying what we’re dealing with. In many English sentences, you have an agent as the grammatical subject, doing something to a patient, the grammatical object. Active voice would give you a sentence like the cat (agent/subject) chased the mouse (patient/object). In the passive voice, the syntactic functions are shuffled, putting the patient ahead of the agent: The mouse was chased by the cat.

To quickly determine whether you’re dealing with passive voice, try the peculiar but practical “zombie test.” Popularized by Marine Corps University provost Rebecca Johnson, it’s a simple rule of thumb for identifying the passive voice. Try adding by zombies after the verb in your sentence. If it makes sense, congratulations! You’ve probably got yourself some passive voice. For example:

- The letter was sent (by zombies) — Passive voice confirmed!

- She was feeling (by zombies) tired — Nope, not passive.

The Blame Game: Who’s Getting It Wrong?

Popular grammar guides have contributed both to what linguist Geoff Pullum calls the “fear and loathing of the English passive” and to the confusion around it. Take The Elements of Style (1918) by William Strunk, the book that activated the passive antipathy. Strunk claimed this sentence is in the passive voice: There were a great number of dead leaves lying on the ground. Plot twist: The zombie test shows it’s not passive at all! Nothing is done to the leaves; they’re just ... there.

Pundits aren’t immune to this confusion either. The Washington Post columnist Alexandra Petri once wrote that “concern trolls thrive on passive constructions.” The sentence she objected to was But her decision to live her cancer onstage invites us to think about it, debate it, learn from it. “Not passive,” say the zombies (and Pullum).

Even an old BBC style guide misidentifies There were riots in several towns in Northern England last night, in which police clashed with stone-throwing youths as employing the passive voice. Of course, it doesn’t.

Why the Confusion?

So why do so many people, even supposed experts, get it wrong? Part of the blame surely lies with the terms active and passive themselves. In the Strunk example above, the leaves aren’t exactly juggling chainsaws, but it’s a mistake to equate physical passivity with the passive voice: I slept is an active sentence, while I was mauled by zombies is pure passive.

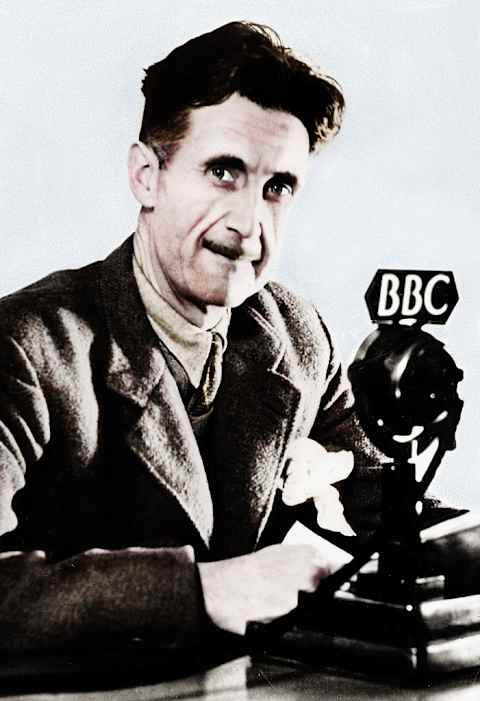

Another issue is the association of passive voice with weak or evasive writing. George Orwell decried it as a tool for avoiding responsibility. If you’ve ever heard someone non-apologize by saying, “Mistakes were made,” you might have asked yourself, “by whom? Zombies?” But blaming the passive voice for evasive writing is like blaming hammers for sore thumbs—it’s all in how you use it. And, when given the opportunity, Orwell chose to use passive verbs 20 percent of the time in his essay “Politics and the English language.” Who’s evasive now, George?

The Secret Power of Passive Voice: Information Packaging

So, what is the passive for? It’s all about how we structure information in a sentence for maximum effect. Consider this paragraph where the subject and topic of each sentence is underlined:

“XYZ Corporation has been a leader in the tech industry for over a decade. Founded in 2010, the company quickly gained a reputation for innovation. In 2015, XYZ Corp was awarded a prestigious industry prize. The company was praised for its commitment to customer satisfaction.”

The passive voice in the last two sentences keeps XYZ Corporation as the focus. But there’s a catch: The trusty zombies test stumbles a bit here. The sentence XYZ Corp was awarded by zombies a prestigious industry prize is a little off. Is this not a passive?

It is indeed passive, but we’re dealing with a tricky construction known as a ditransitive. In active voice, this sentence would have not one object but two: The industry awarded XYZ Corp (indirect object) a prize (direct object). The passive version moves XYZ Corp to the subject position but retains a prize as an object. This is why we can’t actually put by zombies immediately after the verb—the object is in the way. But we can still confirm the sentence is passive by putting by zombies at the end: XYZ Corp was awarded a prize by zombies. The zombie test is useful, but it’s not foolproof.

Regardless of how we identify it, the passive voice serves an important function in information packaging. Here’s another example of how it does this: Where active voice would separate key ideas, passive voice can unite them. Compare these sentences:

- Active: A stack of distinct layers that transform the input volume into an output volume through a differentiable function forms a convoluted neural network architecture.

- Passive: A convoluted neural network architecture is formed by a stack of distinct layers that transform the input volume into an output volume through a differentiable function.

The active version separates the subject stack and the verb forms with a 16-word canyon, while the passive version keeps a cozy neighborliness between the subject architecture and is formed.

Strunk’s passive voice example My first visit to Boston will always be remembered by me is admittedly awful. The problem, though, isn’t about the sentence being less direct or bold, as he claims. Instead, it’s about violating basic rules of how we structure information. In a well-crafted sentence, the beginning bridges the known, while the end blazes the new. This principle explains why Strunk’s example feels so awkward: The speaker—I or me—is almost always common ground, yet the sentence ends by highlighting the speaker’s role as if it needed introduction. Placing by me at the end draws unexpected attention to the speaker’s participation, creating a jarring effect that defies our sense of natural language flow.

So whether you’re writing about your memorable trips or surviving a zombie apocalypse, remember it’s not the passive voice that’s the enemy, but rather the misuse of information structure that will really eat your brains.

Read More About Language:

feed