Myles Burke

Features correspondent

Getty Images

Getty Images

In the 1960s, the BBC set out to investigate local reports of secret, shocking World War Two experiments, dangerous contamination and unexplained animal deaths on a remote island off the coast of Scotland.

"Hereabouts, they call it the island of death, the mystery Island, and for good reason," said windswept BBC reporter Fyfe Robertson as he stood across the sea from the remote and desolate Scottish island of Gruinard in 1962.

"Now, this is not a story of old dark deeds or Highland superstition. No, this story started in 1942. The war had been going on for three years when suddenly a group of scientific boffins from the War Office took over the island and started experiments so secret that even today, 20 years later, very few people know what went on over there. The local people were told nothing."

Robertson was aiming to investigate the stories of dangerous government experiments that were believed to have happened on Gruinard. At the time he was reporting, the UK's Ministry of Defence had already declared the island off-limits and Robertson couldn't persuade fearful locals to sail him around the island to get a closer look at it.

It was an environmental catastrophe. Shockingly, the island remained dangerously contaminated and a no-go area for nearly half a century, until, on this day in 1990, the UK government finally declared Gruinard Island safe.

The truth was that Gruinard Island had been the site of a clandestine attempt by the UK during World War Two to weaponise anthrax, a deadly bacterial infection. The exact details of what had happened there would only come to light when in 1997 the government declassified a film that the military had shot at the time, which detailed the experiments.

Symptoms of infection can take time to fully appear but when they do they are horrific and can become lethal very quickly

The project, called Operation Vegetarian, had started under Paul Fildes, then head of the biology department at Porton Down, a military facility in Wiltshire, England, that still exists today.

Porton Down had first been established in 1916 as the War Department Experimental Station to study the effects of chemical weapon agents, which were increasingly being used as World War One progressed. In the 1940s, with Britain at war again, Porton Down was charged with developing biological weapons that could be used against Nazi Germany to catastrophic effect, minimising actual direct combat between troops.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The plan was to infect linseed cakes with Anthrax spores and drop them by plane into cattle pastures around Germany. The cows would eat the cakes and contract anthrax, as would those who ate the infected meat. Anthrax is a naturally occurring but deadly organism. Symptoms of infection can take time to fully appear but when they do they are horrific and can become lethal very quickly. The proposed plan would have decimated Germany's meat supply, and triggered a nationwide anthrax contamination, resulting in an enormous death toll.

But to get to grips with how anthrax would work as a weapon in a realistic setting, researchers needed an outdoor site far away from populated areas to test it. In the summer of 1942, the military bought the remote, uninhabited 522-acre island of Gruinard, and banned locals from landing there.

More like this:

A military team, under the supervision of scientists, then began to conduct chilling experiments. Using livestock brought over to the island to serve as test subjects, they started a series of trials releasing anthrax spores across the island's terrain.

"The aim was to test whether the Anthrax would survive an explosion in the field, they didn't know that, and then would it remain virulent thereafter," Edward Spiers, emeritus professor at the University of Leeds told the BBC documentary The Mystery of Anthrax Island in 2022.

"Eighty-odd sheep were tethered at various stages downwind of the likely explosion. The explosion was done by remote control. It isn't a great bang, a draught of highly potent spores moving down on the wind and causing infection and death wherever it goes."

The results were devastating: within days of exposure the sheep started showing symptoms and rapidly began to die. Their infected bodies were autopsied and then incinerated or buried under tonnes of rubble.

Some of these experiments were witnessed by local crofters who spotted the drifting clouds of anthrax over the island. One local, who had sold sheep to the scientific team, recalled that he saw what he described as smoke coming down on top of the animals. "I think it was all kinds of poison gas, anthrax," he told Robertson in 1962.

The secret trials carried on until 1943, when the military deemed them a success, and scientists packed up and returned to Porton Down. As a result five million linseed cakes laced with Anthrax were produced but the plan was ultimately abandoned as the Allies' Normandy invasion progressed, leading the cakes to be destroyed after the war. By 1952, Britain had developed a different weapon of mass destruction and had succeeded in its ambition to become the third nuclear power in the world. Four years later it ended its offensive chemical and biological weapons programmes, and in 1975 ratified the Biological Weapons Convention, which bans all use, production or stockpiling of them.

'Operation vegetarian'

The aftermath of Operation Vegetarian was catastrophic to the island. Anthrax is a very resistant bacteria and can persist for decades in the soil, causing infection when ingested even years after an outbreak. The military's experiments had left the island too dangerous for people or animals to live on, with even the rainwater washing from the island being potentially lethal.

In the months following the tests, animals on the mainland near Gruinard Bay began dying. As Elizabeth Willis cites in her paper, Contamination and Compensation, the UK government quietly paid out compensation to those affected but claimed the deaths were the result of a diseased sheep that had fallen off a passing Greek ship.

One local told the BBC in 1962: "It was quite obvious to us that they knew something about it or they wouldn't have paid up so quick as they did."

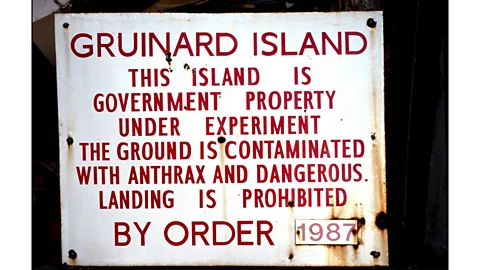

The military quarantined the island indefinitely, and put up signs warning away visitors.

In the decades that followed the end of World War Two, attempts were made to decontaminate the site using chemical treatments and controlled burning, but they proved largely ineffective. A series of tests in 1971 showed that while there were no longer anthrax spores on the surface, they still lingered on in the soil underneath, posing a grave risk to anyone setting foot on the island.

Getty Images

Getty Images

In 1981, an environmental group called the Dark Harvest Commandos landed on the island and took samples of anthrax-infected soil. They left a bucket of that soil outside Porton Down to highlight the deadly contamination on the island, aiming to force the government to do something.

Five years later, scientists returned to try decontamination efforts again, soaking the island in a mixture of seawater and formaldehyde, as well as removing and incinerating contaminated topsoil. This time they were more successful and finally, on 24 April 1990, after 48 years of quarantine, the UK Government declared Gruinard Island anthrax-free.

Gruinard was not the only site where the UK conducted secret biological warfare tests, but it was the first. The consequences of what happened there stand as a grim testament to both the dangers of biological warfare and humanity's capacity for destruction.

--

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the In History newsletter to discover more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, every Thursday.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.