Siberia to Brazil, Climate-Fueled Wildfires Move Underground

In just over five years, the world will arrive at its first major checkpoint on climate action: a 2030 deadline to meet a series of green targets aimed at avoiding the most devastating impacts of global warming.

These goals, set by governments, Wall Street, Big Tech and major polluting companies, are intended to put the global economy on a path to finally start reducing the amount of greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere. Yet, far from being in retreat, carbon dioxide emissions hit a new record last year. That means the world faces a steeper, far costlier and more disruptive journey to reach net zero by 2050.

And that was before the re-election of Donald Trump. With a second term in the White House running until 2029, Trump is unlikely to steer the world’s second-biggest polluter to decarbonize faster than the current pace. In fact, Trump has vowed to undo many of the nation’s expansive climate policies and withdraw from global cooperation. The consequences will extend far beyond the US.

Even before any new slowdown resulting from last week’s monumental political shift, many targets pegged to 2030 deadlines are already in severe jeopardy. An exclusive analysis by Bloomberg Green finds that dramatic acceleration across many fronts would be required to hit end-of-decade milestones on the path to net zero. There are isolated pockets of progress, though those are rare exceptions.

Each year the world falls behind increases the risks of more extreme weather that will put millions of people at risk and threaten global economic growth. One recent assessment forecasts a 1C rise in temperatures would equate to a 12% hit to the world’s gross domestic product. “There are real impacts on people, planet, on industries, on economies, if we miss these goals,” says Sherry Madera, chief executive officer of CDP, a nonprofit that pushes companies and governments to disclose data on their climate impact.

Here’s a reality check on how current progress matches up to crucial 2030 targets.

More than 130 nations agreed at COP28 in Dubai last year to triple the deployment of renewable energy by 2030. The International Energy Agency estimates that solar capacity increased about 40-fold between 2010 and 2023, as wind power expanded around six-fold. But as COP29 gets underway in Azerbaijan this week even that dizzying pace of deployment isn’t sufficient to ensure the world hits its target.

Renewable capacity needs to be added faster or will fall short of target

2x

3x

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

Note: Incremental target and projection based on compound annual growth rate.

About half a terawatt of renewable energy was added globally in 2023, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, meaning there’s still 7.3 TW left to go by 2030. That will require building clean power sources equivalent to more than 80% of the world’s total current electricity-generating capacity, which was just short of 9 TW at the end of last year. To make that happen, around $1 trillion a year will have to pour into the sector through the end of the decade, compared to $623 billion in 2023, according to BloombergNEF.

To triple renewable capacity, the world needs a lot more wind and solar

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

Note: Hydropower excluding pumped

Clean energy growth will have to keep up with soaring electricity demand from China, India and a swath of emerging economies. “Electricity is used more and more in everything — in cars, in industry, at home,” says IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol. “We are entering the age of electricity.”

Renewable growth had two main drivers last year: China and solar

Renewables capacity, in megawatts

2022

2022-23 increase

Promises by the world’s biggest technology companies to aggressively cut emissions — including pledges by Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Meta Platforms Inc. to hit net zero by 2030 — are being upended by the rise of artificial intelligence. While Bill Gates and others believe the technology will ultimately deliver better solutions to accelerate climate action, the need for energy-hungry data processing capacity is delaying progress in the shorter term.

Google’s emissions are roughly two-thirds higher in most recent annual data than in 2020, with Meta reporting about a 64% increase. Electricity consumption by the Facebook owner’s data centers globally jumped more than a third in 2023 to almost 15 million megawatt hours, and has tripled since 2019. Microsoft Corp.’s carbon footprint has risen more than 40% since 2020.

While Amazon.com Inc. has reported falling pollution for the past two years, the company has faced scrutiny over its use of renewable energy credits. Apple, however, says efforts to deploy more clean energy in manufacturing and improved recycling have cut its emissions by more than half since 2015.

Generative AI is challenging emissions targets as power demand grows

Amazon

Net zero by 2040

Apple

Carbon neutral by 2030

Net zero by 2030

Microsoft

Carbon negative by 2030

Meta

Net zero by 2030

Source: Company sustainability reports

Note: For company emissions data, Amazon: market-based calculations for Scope 2 and Scope 3. Apple: market-based for S2, and some segments of S3. Google and Microsoft: market-based for S2. Meta: market-based for S1, S2 and S3. Company also provides location-based emissions data. For pledges, Meta has pledged to reduce S1, S2 emissions 42% in 2031 from a 2021 baseline, and that S3 emissions won’t exceed the same baseline by that date.

Tech giants are pushing to quickly add more clean power, including through the revival and development of nuclear capacity. Microsoft’s recent deal with Constellation Energy Corp. will underpin the restart of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania.

In lower cost data processing and manufacturing hubs in Asia — where fossil fuel-reliant grids still proliferate — the focus so far has been on deals for renewables.

At a former golf course in Inzai, eastern Japan, rows of solar panels are being installed to provide renewable power to a Google data center. About five hours drive to the west, another vast array began operations in February to serve Microsoft’s growing energy needs.

“We’re really looking for what makes the most economic sense and yields the greatest reduction of carbon,” says Amanda Peterson Corio, global head of data center energy at Google. “That could look like solar or wind, or short or long duration storage. It could look like hydrogen, it could look like geothermal,” or other solutions.

Data centers at Meta are increasingly consuming more electricity

Leaders from more than 130 nations, which together account for more than 90% of the world’s forests, committed in 2021 to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by the end of the decade.

About 6.4 million hectares of forests were lost in 2023, 45% higher than the rate required to put the world on a pathway to meet the 2030 target, according to the Forest Declaration Assessment.

Deforestation is increasing, despite pledge to stop losses by 2030

Sources: Forest Declaration Assessment October 2024; Forest declaration Dashboard

Note: Assessment of global progress toward achieving ’zero gross deforestation’, meaning a permanent change in land use from forest to non-forest and the clearing of primary forests, irrespective of any forest gains.

Forests play an essential role in combating climate change, absorbing billions of tons of carbon dioxide each year. They’re also increasingly vulnerable: cleared to grow commodities like soy and palm oil or host mining, logged for timber and burned through intensifying wildfires.

Deforestation rates now need to fall even faster each year if the practice is to stop by 2030, a target first set at the 2014 Climate Summit in New York. Doing so will require addressing a potent cocktail of poverty and commercial interests — not to mention the world’s insatiable appetite for everything from prime rib to gold and copper.

Many of the 28 million people who live in Brazil’s Amazon region, home to the world’s largest rainforest, are poor subsistence farmers who typically burn down sections of the forest to plant crops. They lack money for fertilizer, and so when their soil is depleted they stake out a new patch of land.

President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s efforts to tackle the issue — including increased remote surveillance and penalties that restrict offenders’ access to loans — are having an impact. Brazil cut the rate of deforestation 50% in 2023 and made further gains this year, Marina Silva, the country’s environment minister, said last month, citing government data.

There’s a huge push to develop new financial mechanisms, from carbon offsets to special funds, to generate different forms of income and incentivize people to keep the trees in their communities standing. “You can’t just do this by command and control,” Silva says. “We need a new finance mechanism for forest protection.”

Read More: The Race to Map the World and Protect $110 Billion of Trade

The European Union has also attempted to take a different approach — implementing stricter anti-deforestation standards on nations that export products including coffee, cocoa, soy and beef to the bloc. But the rules have been pushed back by a year after strong objections from many of the EU’s trading partners.

Sales of EVs — from regular sedans to buses and trucks — will have to continue to rise sharply to erase road transport emissions. Electric models need to account for 70% of new car purchases in 2030 to keep the sector on a net zero path, BNEF forecasts.

Electric vehicle sales are forecast to reach at least 45% by 2030. It’s still not enough to stay on track for net-zero

Source: BloombergNEF Long-Term Electric Vehicle Outlook 2024

Note: Share of global passenger vehicle sales. Electric vehicles include battery electric and plug-in hybrids.

Adoption of emissions-free vehicles is one of the few areas where the pace of growth has been positive. The rising share of battery-powered transport could potentially eliminate the need for 6 million barrels of oil a day by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.

About 16.6 million new electric cars will be sold this year, and more than 30 million in 2027, BNEF forecasts, a shift that’s transforming a passenger vehicle segment that currently accounts for more than half of all road transport emissions.

In a base case scenario, where governments add no new policy support, EVs should account for 45% of new car sales in 2030. To be fully on track to reach net zero that share needs to rise to 70%, a feat that’s achievable with only moderate additional measures, BNEF says.

Decarbonization of municipal buses and two-wheelers is already even further ahead, while the tiny market for three-wheeled vehicles is definitively on track.

After several years of strong momentum, there are warning signals — and not only Trump’s often critical view of a technology he’s claimed can only be a “small slice” of the overall auto industry.

Sales growth has cooled in some key markets, and major brands including Mercedes-Benz Group AG have rolled back ambitions. Since late last year a group of 14 legacy automakers — who jointly accounted for more than 40% of EV sales in 2023 — have lowered their collective 2030 sales targets by about 3.3 million vehicles, BNEF calculations show.

Even Tesla Inc. has prompted questions about its strategy. A key annual document replaced a previous ambition to deliver 20 million vehicles a year by 2030 with a less specific goal to sell as many products as possible.

“The transition to electrification will not be linear, and customers and markets are moving at different speeds,” Volvo Car AB CEO Jim Rowan said in September, as the producer removed a goal to sell only plug-in models by the end of the decade.

Almost 200 nations committed to protect 30% of the world’s land and waters by the end of the decade through the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. That will keep more carbon buried in the ground and limit the risks of extinction faced by threatened species.

The diversity and abundance of life on the planet is shrinking faster than at any point in human history. Just 17.6% of land and inland waters are under protection and 8.4% of oceans. “Far more needs to be done if the world is to deliver on 30x30,” says Susan Lieberman, vice president of international policy at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Protected land and inland waters must increase by 2% each year to 2030, and marine areas by 4%

Source: Protected Planet

Note: Rate of progress based on average annual increase since pledge. Shows progress on terrestrial and inland waters protected area including OECM coverage, and Marine protected area & OECM coverage as of Nov. 11, 2024

The first round of United Nations talks to assess progress since the Kunming-Montreal pact was signed in 2022 fell apart earlier this month in Colombia after nations failed to agree on how to raise more funds for nature. Parties at the 16th UN Biodiversity Conference nonetheless managed to agree on a new process to identify marine areas most in need of protection — a development that’s expected to spur progress toward meeting the goal.

Some countries are doing better than others. In Germany, 39% of terrestrial and inland waters and 45% of marine life is already protected, according to Protected Planet. The US, which is not a signatory to the pact, has protected 13% and 19%, respectively. When it comes to oceans, China has protected less than 5%, Protected Planet shows. “The gap between pledge and action is vast,” says Beth Pike, director of the Marine Protection Atlas at the Marine Conservation Institute. Four countries have increased marine protection by 5% or more since the pact was signed in 2022: Comoros, Oman, France and Australia. The slow progress reflects a lack of “meaningful pressure on countries to hit these targets,” said Alistair Purdie, a biodiversity analyst at BNEF. The pact “isn’t legally binding, so what’s their incentive to actually protect 30% of potentially value generating land and waters?” he said.

Fashion brands and textiles producers want to limit emissions and reduce their consumption of energy and water. Textile Exchange, a nonprofit with more than 800 members — from cotton growers to brands like Chanel Ltd., Nike Inc. and Lululemon Athletica Inc. — is targeting a 45% cut in the sector’s greenhouse gasses by the end of the decade.

Emissions from global production of textiles rose about 4% between 2019 and 2022, and are off track for a 45% reduction by 2030

Source: Textile Exchange

The rise of fast fashion is a major hurdle. “We are overconsuming clothing,” said Claire Bergkamp, Textile Exchange’s chief executive officer. “That disposable mindset is a huge issue for achieving any of the climate goals.”

The insatiable demand for cheap and trendy clothes pushed global production of fibers to 124 million tons in 2023, and per capita consumption has almost doubled since 1975, according to the nonprofit’s data. It doesn’t help that companies are increasingly turning to fossil fuel–based polyester, while textile recycling isn’t making much progress.

Water usage is another major challenge. Producing a single cotton T-shirt can require as a much as 2,700 liters of water — about the same volume needed to sustain a person for 900 days, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE, which owns luxury brands like Givenchy and Christian Dior, says improving water stewardship is “the next frontier.” The group — which operates water guzzling leather tanneries, crocodile farms and vineyards — has pledged to cut its usage by 30% by 2030, though consumption for processes rose last year.

About 130 businesses, including retailers Marks and Spencer Plc and Primark, have signed a similar pledge led by UK-based nonprofit WRAP. Water consumption among the group increased 8% in 2022.

For a group of about 130 textile and fashion businesses, water consumption is up 8% since 2019

Source: WRAP

To limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels — a threshold seen as crucial to avoid more severe impacts on people and ecosystems — the world’s annual emissions need to fall 42% by 2030, the UN Environment Programme says.

Emissions rose 1.3% in 2023, and need to decline 7.5% every year until 2035 to meet the target to limit planetary heating.

The emissions gap for a 1.5°C compatible pathway is set to widen by 2030

Sources: Climate Action Tracker 2030 Emissions Gap December 2023

Gains being made in the developed world to cut emissions aren’t currently sufficient to shift the global trajectory, as emerging nations produce an increasingly large carbon footprint. International ambitions may rest on whether economic growth can be decoupled from the burning of fossil fuels.

A group of 10 major developed nations — including the US, Japan and Germany — reduced emissions 4.2% in 2023, cutting their footprint to the lowest level since 1970, according to Fitch Ratings. Among 10 key emerging economies the total rose 4.7%.

Energy consumption is growing rapidly in developing nations, and most have power systems that remain far more reliant on polluting coal and gas. India, already the second-largest coal consuming nation, will add electricity demand faster than any other major economy through 2026, the IEA forecasts.

Spending on renewables to decarbonize power systems remains modest outside existing major hubs. China’s investment totalled $130 billion in the first half of 2024, compared to $2.9 billion across Southeast Asia and $15.6 billion in Latin America, according to BNEF. Developing nations aim to use the COP29 negotiations in Baku to demand a huge increase in the flow of climate finance from rich countries to more than $1 trillion a year.

Countries are also being pressed to dramatically increase the ambition shown in their nationally determined contributions — the commitments governments make under the Paris Agreement to cut emissions. A failure to upgrade targets in a new round of pledges — and to deliver immediate progress — risks temperature increases of 2.6C to 3.1C this century, the UNEP said last month.

Nations that have already hit a pollution peak still need to do more to narrow the gap between existing carbon-cutting plans and what’s needed to limit warming to 1.5C. The US needs to make an additional 17% reduction by 2030 to be fully aligned, according to the Network for Greening the Financial System. Though emissions declined during Trump’s first term, there’s little hope that climate policies will be accelerated.

“Everybody should be seeing the opportunity of moving forward — this is a race,” says Catherine McKenna, a former environment and climate minister of Canada, and who led a UN expert group focused on emissions reduction efforts by cities, companies and other non-governmental polluters.

As emissions start to fall in today’s high-income countries, they’ve taken off in growing economies

Source: Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR); World Bank

Note: Income categorizations are based on 2024-25 data

Aviation is counting on one tool more than any other to deliver net-zero emissions by mid-century: so-called sustainable aviation fuels, or SAF. Several major airlines — including American Airlines Group Inc. and Qatar Airways — aim for the lower-polluting alternative to account for 10% of their total fuel consumption by 2030, and the main industry body says about 24 million tons of supply is required by that date.

Use of sustainable fuels for aviation is on pace to hit 1.5 million tons in 2024, but needs to grow 16-fold by 2030 for a net zero path

Source: International Air Transport Association

Note: 2024 capacity is a forecast. 2030 goal is to reach 24 million metric tonnes of fuel from 2024 baseline

Airlines have a seemingly impossible climate challenge. The global aviation industry, which accounts for 2% of existing emissions, aims to reduce its carbon footprint at the same time demand for air travel is ballooning as the global population grows, and becomes richer.

The International Air Transport Association expects SAF to deliver about two-thirds of the sector’s emissions reductions by 2050, and yet the supply outlook already looks bleak. Air New Zealand withdrew its climate targets in July, citing issues including the affordability and availability of cleaner fuels.

There are efforts to change that. While alternative methods to produce SAF will eventually become competitive, for now the industry relies largely on used cooking oil to feed hydroprocessing facilities. But soon there won’t be enough waste to keep pace with expansion of SAF-producing plants.

Each morning around 3 a.m. in neighborhoods close to Tianjin Port on China’s northeastern coast, a fleet of 60 drivers head to local restaurants and fast food outlets to collect the unwanted grease in giant containers or barrels. A team of six researchers tour the same routes, quizzing the owners of mom-and-pop eateries as they attempt to refine their picture of future supply.

Expanding availability of the used oil “remains a concern on our mind,” says Dong Hui, general manager of a unit of Shandong High Speed Renewable Energy Group Ltd., which exports the material to destinations including the US.

Wall Street has pledged to rapidly increase financing of a green transition that’s forecast to need as much as $215 trillion by 2050. A sample group of 10 major lenders have set goals to collectively direct more than $9 trillion toward clean energy and other sustainability objectives.

Green financing is advancing, and the 10 institutions reviewed have deployed more than $4 trillion toward their goals. Still, the wider industry’s ratio of lending to clean energy compared to fossil fuels — a key metric — remains far behind the 4 to 1 rate needed by 2030 to limit temperature rises.

Major banks need to improve the flow of sustainable finance

Source: Company filings

Note: Targets refer to publicly announced figures that include varied combinations of lending, investments and underwriting. Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas and RBC data reflect 2025 goals and converted to dollars at current rate for comparison.

Many of the world’s biggest lenders exited the Covid-19 pandemic with a new enthusiasm to channel trillions of dollars this decade into global efforts to meet climate and sustainability goals.

Headline targets for the financing of climate and sustainability-related activities look eye-catching — at least at first glance — and many institutions are already racing to meet those goals. Morgan Stanley has crossed the 80% threshold toward a $1 trillion benchmark, while Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Royal Bank of Canada, Deutsche Bank AG and BNP Paribas SA are all more than two-thirds of the way along in efforts to meet their own ambitions.

“When some banks get close to, or surpass, their original sustainable finance goals, they set new targets that are significantly bigger,” says Anderson Lee, a researcher at the World Resources Institute, which has studied banks’ sustainable finance statements. “This suggests that their original targets were relatively modest and more can be done.”

Barclays Plc met an original 2030 target to deliver £100 billion ($129 billion) of green financing, and set out a revised plan to direct $1 trillion toward a sweep of sustainability and transition-related requirements.

Still, climate campaigners insist the most important gauge of the sector’s progress is how much banks are investing and lending to green activities and how much they’re continuing to fund fossil fuels.

To limit warming to 1.5C, the ratio of clean energy lending and equity underwriting relative to fossil fuels needs to average a minimum of 4 to 1 through the end of this decade, according to BNEF. Most recent data show that in 2022 that ratio was 0.73 to 1.

(Corrects details of sustainable financing and investment targets for BNP Paribas in the final section.)

Siberia to Brazil, Climate-Fueled Wildfires Move Underground

165 Lawsuits That Could Impact the 2024 Trump-Harris Election Results

Financial Scams Against Seniors Surge as Banks Fail to Protect Wealth

Tracking Hurricane Helene’s Latest Path

Inside China, Iran’s Illicit Oil Trade Hub Off Malaysia, Singapore Coasts

Tracking Hurricane Milton’s Latest Path

US Election: How Migration in Key States Affects Local Economics

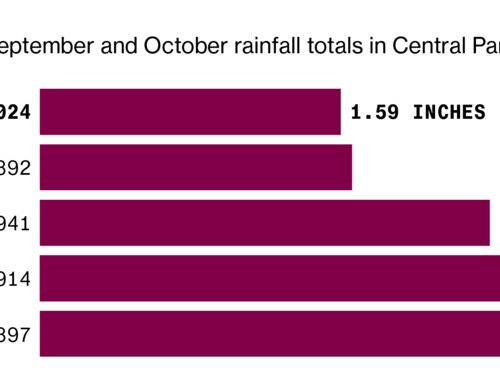

When Will It Rain in New York? City's Driest Fall Ever, Explained