Photographs by Nicola Muirhead

A sudden roar broke the muggy stillness, making me jump.

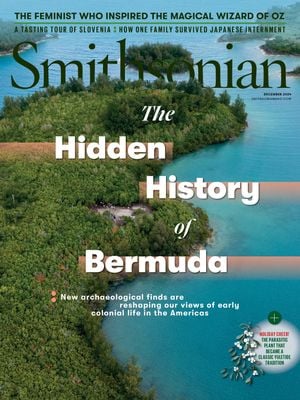

A young woman squatting in a shallow trench reassured me. “No worries,” she said, gesturing with a trowel into a nearby thicket. “Our tools here are chainsaws and leaf blowers.” Whisk brooms, dental picks and spoons are also part of the arsenal. A few dozen yards away, in a dirty T-shirt, faded camo shorts and black work boots, Michael Jarvis hacked away at thick brush with a gas-powered saw. In this clearing on Smith’s Island, in Bermuda, Jarvis—“Chainsaw Mike” to his students—is unearthing one of the first New World towns built by English colonizers.

The settlement was established in 1612, a mere five years after the founding of the Jamestown colony in Virginia and eight years before the Pilgrims stepped ashore at Plymouth, Massachusetts. It was abandoned soon afterward for another location on a nearby island. Its very existence was forgotten for four centuries; even its name remains unknown.

With its pink sands and azure waters, Bermuda has long been a favorite among honeymooners—and overlooked by scholars. Yet the string of about 180 islands in the Sargasso Sea were, for a time, home to more settlers than either Virginia or Massachusetts, and far more prosperous. It was here that the English first grew tobacco in the New World and purchased enslaved Africans to work the fields, a practice that soon spread to American shores. “Bermuda barreled ahead, becoming profitable, and that model encouraged investors who realized they could make money in the New World,” explained Carla Pestana, a historian at the University of California, Los Angeles. “It was the first financially successful plantation.”

The booming archipelago also provided essential food supplies for struggling Jamestown, predated Plymouth as a religiously focused Puritan colony and served as the sole flourishing beacon for early English venture capitalists seeking to make their fortune in the New World. But covering a mere 22 square miles—barely a third the area of Washington, D.C.—the colony’s population was quickly dwarfed by English emigration to North America and the Caribbean. Soon ecological disasters forced planters to become merchants or privateers. As the British Empire expanded around the globe, and the United States was born, the significance of this remote speck of land receded, barely earning a footnote in many chronicles of American colonization. “When historians have thought about Bermuda, it’s as a curiosity or a failure,” Jarvis said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/10/0c107567-6cf8-48ef-822c-be3440716397/dec2024_a11_bermuda.jpg)

For the past 14 years, Jarvis, a historian and archaeologist at the University of Rochester in New York, has led excavations in Bermuda seeking to uncover the secrets of its neglected colonial history. Nobody has done more to shed light on the islands’ important role in fostering the growth of Britain’s overseas realm and its American spinoff. Now he is confident he has located its first substantial settlement. His findings are exciting those who research Europe’s colonization of the New World, given how rare it is to uncover remnants of such an early English community in the Americas. Mark Horton, a British archaeologist digging for remnants of the failed 1587 Roanoke colony on the North Carolina coast, hails it as “a truly significant discovery” that will “greatly help in understanding early 17th-century settlement—not only in Bermuda, but at Jamestown, in New England and across the Caribbean.”

Bermuda, shaped like a fishhook, lies 650 miles east of North Carolina’s Cape Hatteras and 800 miles north of the West Indies, astride the warm Gulf Stream current that courses past the Bahamas and into the North Atlantic. A cooling climate more than a million years ago locked up ice in the polar regions, lowering sea levels and exposing the top of a massive volcano in the mid-Atlantic Ocean that rises 14,000 feet above the sea bottom. In time, warming temperatures raised the water, smoothing and flattening the rough peak, a cycle that repeated itself many times over and gradually formed today’s archipelago with its shallow bays. Meanwhile, the Gulf Stream carried plants and animals, including turtles, insects and the seeds of palms, cedars and mangroves. Among them was the tiny invertebrate that secretes calcium carbonate—the key component of limestone—which slowly built up a network of coral reefs surrounding the islands.

With no mammal predators, an array of birds multiplied, including vast flocks of a seabird called the cahow, a name that mimics its noisy and otherworldly cry. There is no record of people setting foot here until the early 1500s, though some believe Bermuda to be the “isle of birds” visited by St. Brendan, the sixth-century Irish monk and adventurer. Spanish navigator Juan de Bermúdez spotted the chain around 1503, giving it its name. It’s believed that he offloaded pigs so they might feed future Spanish settlers or castaways.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c6/51/c6512ac9-c3a9-47d9-9829-4da049a60018/dec2024_a99_bermuda.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/7c/967cd8ce-8294-4d67-99f4-4804aa7fdbcd/dec2024_a10_bermuda.jpg)

Sixteenth-century seafarers, however, did their best to give the island chain a wide berth. Jagged reefs reaching far into the ocean easily punctured wooden hulls, a threat made more menacing by the unpredictable weather. Sir Walter Raleigh warned that Bermuda was surrounded by “a hellish sea for thunder, lightning and storms.” English captain Francis Wyatt wrote that “all seafaring men”—whether English, French or Portuguese—agreed “that hell is no hell in comparison to” Bermuda’s fierce weather. They avoided the islands “as they would shun the devil himself,” another Englishman, Silvester Jourdain, wrote. Not all succeeded. One of many ships that sank offshore was a Portuguese vessel; a casualty of the wreck survived long enough to carve “1543” into an island rock. This fearsome reputation extended to the land itself. The eerie calls of the cahow were ascribed to demons. One European wrote that Bermuda was “an enchanted den of furies and devils, the most dangerous, unfortunate and forlorn place in the world.” While Europeans scrambled to grab New World territory, the archipelago was considered out of bounds.

This infamous hell became a miraculous heaven on the morning of July 25, 1609. A large English fleet sent to resupply the struggling settlement of Jamestown took a shortcut across the Atlantic, only to encounter a powerful hurricane that scattered the vessels. Amid the relentless pounding of the waves, the hull of the 250-ton flagship, the Sea Venture, filled with seawater. For three terrifying days, expedition leader Sir Thomas Gates exhorted the passengers to work the pumps while Admiral George Somers clung to the helm to guide the foundering ship through titanic swells.

By the third day, death seemed certain; some prayed, while others got drunk. Then, in the morning light, Somers spotted land and steered the sinking ship close to shore, where it wedged tight between two V-shaped rocks. With the storm abating, all 150 people—as well as the ship’s dog—made it safely to a beach on what became known as St. George’s Island. Instead of an “isle of devils,” they found a lush landscape, thick flocks of easily captured birds, herds of fat feral pigs and bountiful marine life. Dazzled by the food and mild climate, many of the shipwreck victims preferred to stay, but Somers and Gates were determined to reach their destination. They built temporary camps, and through the fall and winter, they constructed two sturdy vessels from the local cedar. By spring 1610 they set sail for the Virginia coast, leaving behind two sailors who deserted the mission and were able to thrive on the island.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/57/9c/579c433c-2615-4da0-9d85-1166b580115d/dec2024_a09_bermuda.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6f/0e/6f0efcae-e2b7-4dee-a363-b0ccd1e0824e/dec2024_a14_bermuda.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/aa/bd/aabd0dd4-d75a-4188-a0a9-875e33d000b3/dec2024_a01_bermuda.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/73/5c/735c3310-1fda-4b38-95f7-83ad7b37b3f6/dec2024_a13_bermuda.jpg)

The settlers who departed soon regretted their decision. Arriving at Jamestown, they found the colonists sick, hungry and at odds with the local Algonquian-speaking peoples. The visitors’ stores of food were welcome, but Somers returned to Bermuda to gather additional provisions. He also overindulged, dying in November 1610 of a “surfeit of eating of a pig,” according to historical records. Instead of returning to Virginia, his crew buried the admiral’s heart in Bermudan soil and stowed his body in a cask of whiskey before sailing for England. One of the original deserters and two additional men remained on the island—willing castaways whom American poet Washington Irving later styled “the three kings of Bermuda.” By then, all but 60 of Jamestown’s 500 inhabitants were dead, victims of infighting, incompetence and bullying tactics toward the Indigenous tribes that led to violence.

News of the Sea Venture’s dramatic shipwreck reached London by the fall of 1610, along with tales of an enchanted place that was “abundantly fruitful,” as the Jamestown historian James Horn wrote in 2005. When Shakespeare heard the stories, he wrote a play about a magical spirit-filled island, referred to at one point as the “Bermoothes.” The King’s Men thespians first performed The Tempest for James I and the royal court on November 1, 1611. By then, the desperate situation in Virginia was well known in England, spooking investors who feared that no New World settlement would thrive. “Remember that three out of four English settlements had failed,” Jarvis said, citing two attempts to settle North Carolina’s Roanoke Island and another to colonize Maine. “And Jamestown was only barely surviving.”

Bermuda suddenly beckoned as a more promising prospect. A little more than six months after the play’s debut, a small vessel called the Plough was on its way to settle the island chain. While Jamestown was an all-male effort, women and children joined the new venture, though their names are lost to history. Among the 60 passengers were several who were hostile to the Church of England and eager to find a place to practice their more austere form of Christianity. This was also in contrast to Jamestown, which primarily drew those looking for easy wealth rather than a religious haven. And instead of placing an inept aristocrat in charge of the venture, the sponsoring Virginia Company wisely chose an experienced carpenter named Richard Moore.

After an uneventful nine-week voyage, the ship’s captain threaded his way through one of the island’s only deepwater channels, likely using a map drawn by Somers. On July 11, 1612, the vessel dropped anchor in a spacious harbor dotted with wooded isles. While the settlers said a prayer of thanksgiving, the crew caught enough fish to feed everyone.

The next day, Bermuda’s “three kings” made their presence known. Over the course of their two-year stay, the trio had built a small homestead on Smith’s Island, an oblong-shaped piece of land twice the size of Ellis Island in New York Harbor. A cleared acre had yielded corn, pumpkins and beans, which they stored away along with copious amounts of salted pork and tortoise meat. The supplies would have heartened colonists who no doubt had heard grim tales of cannibalism at Jamestown.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/66/c0665459-4510-467d-b5a9-c1853df46853/dec2024_a07_bermuda.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/c1/17c1b095-20c8-408f-a6f3-0277b6025851/dec2024_a03_bermuda.jpg)

Governor Moore “presently landed his goods and 60 persons … upon the south side of Smith’s Isle,” one contemporary wrote. The colonists found a variety of fruits and vegetables already growing, including thriving cucumbers and melons. The settlement would have included a meeting house or church, storage buildings, a scatter of residences and a grander home for the governor. Military barracks or a palisade would have been superfluous. “Unlike Jamestown and Plymouth, there were no Indigenous people, and this made Bermuda a blank canvas,” said Pestana, who recently made the trek to Smith’s Island, volunteering to dig, sift and wash artifacts. The Spanish were the only threat, but Moore had a rudimentary fort constructed on a nearby island armed with a cannon salvaged from the Sea Venture to protect the settlers from England’s great rival.

The town proved short-lived. Within months the governor “removed his seat from Smith’s Island to St. George’s after he had fitted up some small cabins of palmetto leaves for his wife and family,” wrote Plough passenger John Smith. Jarvis suspects the shift to this larger island took place in mid-fall 1612, perhaps due to the lack of arable land and adequate fresh water. The colonists would have likely dismantled what they could to build their new center of St. George’s, which remained Bermuda’s capital for the next two centuries. (Today the capital is Hamilton, on Main Island, to the southwest.)

Smith’s Island’s brief moment as the home of Bermuda’s first town was quickly forgotten. The area eventually served as a quarantine camp for those who arrived with communicable diseases; the body of water off the island’s southeastern end was dubbed Smallpox Bay. While much of the island chain became thickly settled, Smith’s Island remained a quiet backwater. When a hydroponics business on the eastern third of the island failed in the 1970s, the land was turned into a national park and quickly reverted to jungle. Beneath that tangled mass lay one of the oldest English towns in the New World.

The sun was just rising, but already disco music blared from a loudspeaker mounted to the stately 18th-century St. George’s Town Hall. A scruffy Boston whaler with Jarvis at the helm puttered up to the wharf, and a half-dozen passengers climbed out. These students and researchers, who spent their nights on a nearby island, would toil during the day in the basement of the town museum, cataloging artifacts found at the dig. After they disembarked, I joined a group of local volunteers for the ten-minute voyage across the harbor to Smith’s Island, where they would assist in that day’s excavation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/df/24dfca70-b3b0-49c2-b093-b30c87b0bbf5/dec2024_a06_bermuda.jpg)

Once we arrived, Jarvis secured the boat to the dock and led us single file on a path through thick foliage. “Everything originally was covered with palmetto and cedar,” he said over his shoulder. The palmetto berries fed the hogs introduced by the Spanish, and the cedar, strong as oak but much lighter, proved ideal for building ships. Bermuda’s settlers instituted strict rules to protect this latter commodity, but a blight that began in the 1940s killed off these park-like forests and opened the way for invasive plants. By the time Jarvis arrived in 2010, the vegetation was dense. The first task was to clear the brush.

Soft-spoken despite a football player’s build, Jarvis learned to handle a handsaw while growing up in rural Pennsylvania, where he spent long hours outdoors. He conquered his fear of chainsaws just a few years ago. His grandfather and uncle were blacksmiths, and at a summer job at a New Jersey maritime village he worked the forge, making harpoons and hooks to sell to tourists. “I gravitated to colonial history because I was always interested in getting at the origins of our nation’s history,” he said. In college, Jarvis focused on experimental archaeology, which attempts to replicate the way individuals made things and performed various tasks. “It’s a way to understand the past by knowing what people then actually did,” Jarvis said. He also taught a semester at sea on a schooner, cruising the Caribbean. “Hauling lines and going aloft, you gain insights that only come by doing what they did back then,” he said. While working toward his doctorate in history at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, he dug in trenches within the historic area of what was Virginia’s second capital.

In 1995, Jarvis joined the team led by the archaeologist William Kelso that uncovered the original fort at the first capital of Jamestown, a site long thought to have succumbed to river erosion. That dig exposed what is widely considered the most significant find from colonial America. Some surprises were cahow bones, tropical fish skeletons, sea turtle shells and large pig bones. Archaeologists agreed that these were Bermuda imports that helped sustain the hungry Virginia colonists. They even found tobacco pipes and building blocks from the islands’ limestone quarries, underscoring the close relations between the two early settlements. Virginia Company records show that vessels coming from England regularly stopped at the archipelago on their way to Virginia.

Those discoveries whetted the young academic’s curiosity. Years earlier, as a student, Jarvis had done a stint on one of the few excavations on the island chain. Now, he turned his attention to its early colonizing efforts, poring through the historical record for clues before launching his on-the-ground search for Bermuda’s version of Jamestown. More than a decade later, he believes he has found where the passengers of the Plough built their first settlement.

Now 56, the archaeologist, leading us down the narrow trail toward the island’s east end, detoured into a small opening in the brush that sloped downhill. A few dozen yards down the narrow trail stood a natural stone wall punctured by a round hole the size of a barrel. Though the evidence remains sketchy, Jarvis is confident this marks the home of the “three kings” who greeted the Plough settlers in 1612. “This style of bake oven, a cave hearth, processes meat and bread,” he said, pointing out indentations in the stone where timber posts would have rested, perhaps to hold up a small lean-to with a thatched roof. “It was a good location, hidden from the Spanish and protected from the prevailing winds during storms.”

A team of archaeology students and volunteers uncovered mature boar tusks here, suggesting they were used before the 1620s, when the last large feral pigs vanished into colonists’ cooking pots. Farther down the slope was a cove called Cotton Hole Bight. “We know they built shallops”—a small boat popular in that era—“and this is a good place to launch vessels.”

Back on the main trail, we hiked another hundred yards until the narrow path opened into a broad clearing. Under two large tarps, a couple of dozen excavators were brushing and scraping away at the soil and rock. “We have a map of Jamestown, but there is nothing for the initial settlement here,” Jarvis said. “Archaeology is absolutely necessary to figure out the location—history won’t help us.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/f5/8df575eb-cfcb-4e6e-acbf-4e5ffaafe4c2/dec2024_a02_bermuda.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/da/5d/da5d4f0f-6599-4228-976a-eeb47c8ee5fb/dec2024_a04_bermuda.jpg)

At the center of the clearing stood the ruin of a small building of Bermuda limestone. Faded letters on an inside wall still read “GR,” which stands for King George. In 1780, the British Army garrisoned the islands, and the structure likely was built in 1790 to cope with the yellow fever epidemic. A dozen yards north of the ruin, beneath a blue tarp, members of Jarvis’ team were slowly gathering evidence of Moore’s first town.

Before putting a spade in the ground, team members use a device that looks like a bulky lawn mower to probe what lies beneath. That requires clearing the land of invasive brush, which is why Jarvis’ chainsaw is essential. This ground-

penetrating radar showed depressions in the limestone bedrock beneath the shallow topsoil, though buried debris can create false signals. Such results can guide excavators to the most promising areas to dig with their hand trowels.

The best markers for an early 17th-century English building are not foundations but round holes. Carpenters would dig and sink vertical posts into the ground at regular intervals to hold a timber frame, often separated by three feet. They would then add studs between the posts and fill the remaining area with flexible branches—known as wattles—that then would be coated with thick clay, a material called daub. This wattle-and-daub method was used by Jamestown and Plymouth settlers as well, but pinpointing the remains of such ephemeral structures is often difficult; the telltale postholes often are hard to discern, buried under four centuries of soil. Fortunately for Jarvis, Bermuda’s early settlers used hoes and other tools to bore deep into the soft limestone, leaving behind clear traces beneath the thin layer of earth.

“A clutch of roots can be a sign of a posthole,” explained Olivia Adderley, a native Bermudian who recently spent time in Britain studying archaeology. “Then we use a whisk broom and trowel to expose each feature.” She thrust a nail with a red plastic flag into one likely posthole, setting it aside for more careful excavation later. Though the posts themselves appear to have been removed after the capital moved to St. George’s, she added, “we have tool marks and shims” that show these are human-made rather than natural features. Walking over to a cavity recently dug out, she reached her arm into it, and it vanished almost to her shoulder. Such deep postholes are evidence of a building with sturdy walls that may have risen to two stories.

Material swept into the holes provides additional clues. Undisturbed for four centuries, these pockets reveal convincing evidence that the people who lived at this site were the settlers from the Plough. “Sealed sites from that time period are few and far between,” said Bly Straube, an archaeologist who worked at the Jamestown excavations and now is senior curator at the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation. The researchers have recovered fragments of a remarkably durable daub that Jarvis said bears an uncanny resemblance to cement used in ancient Rome. And the many broken bits of pottery can be used as reliable dating tools, since styles changed across the eras. “The ceramics are consistent with the material found on the Sea Venture and at early Jamestown,” Jarvis asserted. Straube says additional analysis is underway to confirm the claim. If Jarvis proves correct, the site is from the 1610s, precisely in the window when the Plough arrived.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/5b/cd5bb128-921f-487d-a0ca-2eec76b3bff1/dec2024_a05_bermuda.jpg)

Bones in the postholes also offer insight into what colonists ate—and when. An abundance of fish skeletons was hardly remarkable, but there was a puzzling lack of cahow. The bird was plentiful in the early years of settlement and such a major source of nutrition for colonists that they nearly went extinct within a decade or so. The lack of cahow remains therefore suggested the settlement was from a later date. “Then we realized that the flocks migrate to Bermuda in the late fall—after the colonists had likely already moved to St. George’s,” said Jarvis. “So the absence of their bones is actually evidence that this is the first town.”

So far, the researchers have identified two distinct structures, including what appears to be a modest building measuring 12 by 16 feet. This was likely a home for one of the families who traveled on the Plough. The second is 16 feet wide and at least 30 feet long. “We had no idea we would find something this large—and we haven’t found the end of it yet,” Jarvis explained. “But we have found what is likely a door.” If this was placed in the center of the wall, then the building is 32 feet long. “In that case, it would have resembled the church at Jamestown, and possibly been two stories.” Records show that an Anglican minister held divine services, and any church would have been in the town center. Once fully mapped, the large structure could help Jarvis piece together the rest of the settlement’s layout.

As many as ten private dwellings would have made up the bulk of the town. So far, a scatter of other postholes suggests the remains of at least three or four. In future digging seasons, Jarvis hopes to create a map of streets, lanes and structures to flesh out the size and orientation of the settlement. Just to the west of the possible meeting house, excavators found a small piece of lead that once held panes of glass in place, at a time when such windows were reserved for the wealthy. “This suggests a high-status individual”—perhaps Governor Moore—“and gives us a tantalizing hint of class differences among the houses,” the archaeologist added. “As we study each building, we expect to see a hierarchy of class emerge.”

All the soil exposed during the dig is screened nearby to recover small artifacts, and each day’s finds are then sent across the harbor to the St. George’s lab for cataloging. Analysis of these helps researchers discern how early English colonists organized their new society. “We want to know how Bermuda’s first town both resembled and was different from the other English colonial prototypes,” Jarvis said. So far, Moore’s settlement appears to have been a unique hybrid of Jamestown and Plymouth. Like the former, it may have had a traditional Anglican-style church, yet, like the latter, it was constructed less like a military camp and more as a village with separate dwellings for families.

In the decade after the Plough’s arrival, English settlers flocked to Bermuda, including more ascetic Protestants hoping to create a perfect society on their island Garden of Eden. Their example encouraged those with similar beliefs to view America as a haven for Puritan-minded people. By then, Bermuda was booming, with an English population outstripping that of either Virginia or New England.

Tobacco had already been noted on the islands by Sea Venture castaway John Rolfe, famed for later marrying the Powhatan princess Pocahontas at Jamestown. It was planted by an earlier Spanish castaway, and Rolfe used the Bermuda tobacco seeds in Virginia around 1612 or 1614, creating an export that saved Jamestown from financial disaster. Bermudians had a head start. The “three kings” already had “made a great deal of tobacco,” and one early settler predicted cultivating the crop would be “very commodious both to the merchant and to the maker of it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/95/e2/95e298f8-18bb-4cdb-9719-f1b145ce7be3/dec2024_a08_bermuda.jpg)

White colonists first brought a single enslaved Black laborer from the West Indies to Bermuda in 1616—three years before Black people in bondage landed in Virginia. More followed. Those who had labored on West Indian tobacco plantations, and were familiar with the crop, were particularly prized. It was only in 1624 that Virginia’s tobacco exports to England exceeded that of Bermuda. Eventually, tobacco’s deleterious effects on the soil, as well as the limited land, ended the islands’ brief boom. Meanwhile, European ships brought rats that devoured food supplies and wreaked havoc on the ecosystem. Settlers wantonly killed flocks of cahow and other birds, while deforestation added to the swift economic decline.

Colonists rapidly pivoted from farming to shipbuilding, trading and privateering, and many of the enslaved laborers became sailors and stevedores. Fast and sturdy Bermudian ships soon crisscrossed the ocean, stimulating business in a vast arc from the West Indies to Newfoundland, while seizing enemy vessels as European powers fought to dominate the New World. Memory of the islands’ origins as a kind of paradise and then a tobacco powerhouse that briefly outshone their sister settlement in Virginia waned. A century later, when that colony joined the rebellion against Britain, Bermuda stayed within the empire, and today it is a self-governing British territory.

Shakespeare concluded The Tempest by predicting that everything “shall dissolve and, like this insubstantial pageant faded, leave not a rack behind.” Yet Jarvis and his team are recovering Bermuda’s vanished story. In 2023, William Kelso visited Smith’s Island to check on his protégé’s work. “Archaeology is like a play,” said the retired Jamestown excavator. “The set is the landscape, and the script—the history—is usually all torn up and falling apart. Mike is pulling it all together and casting Bermuda in three dimensions.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?