None of this was inevitable.

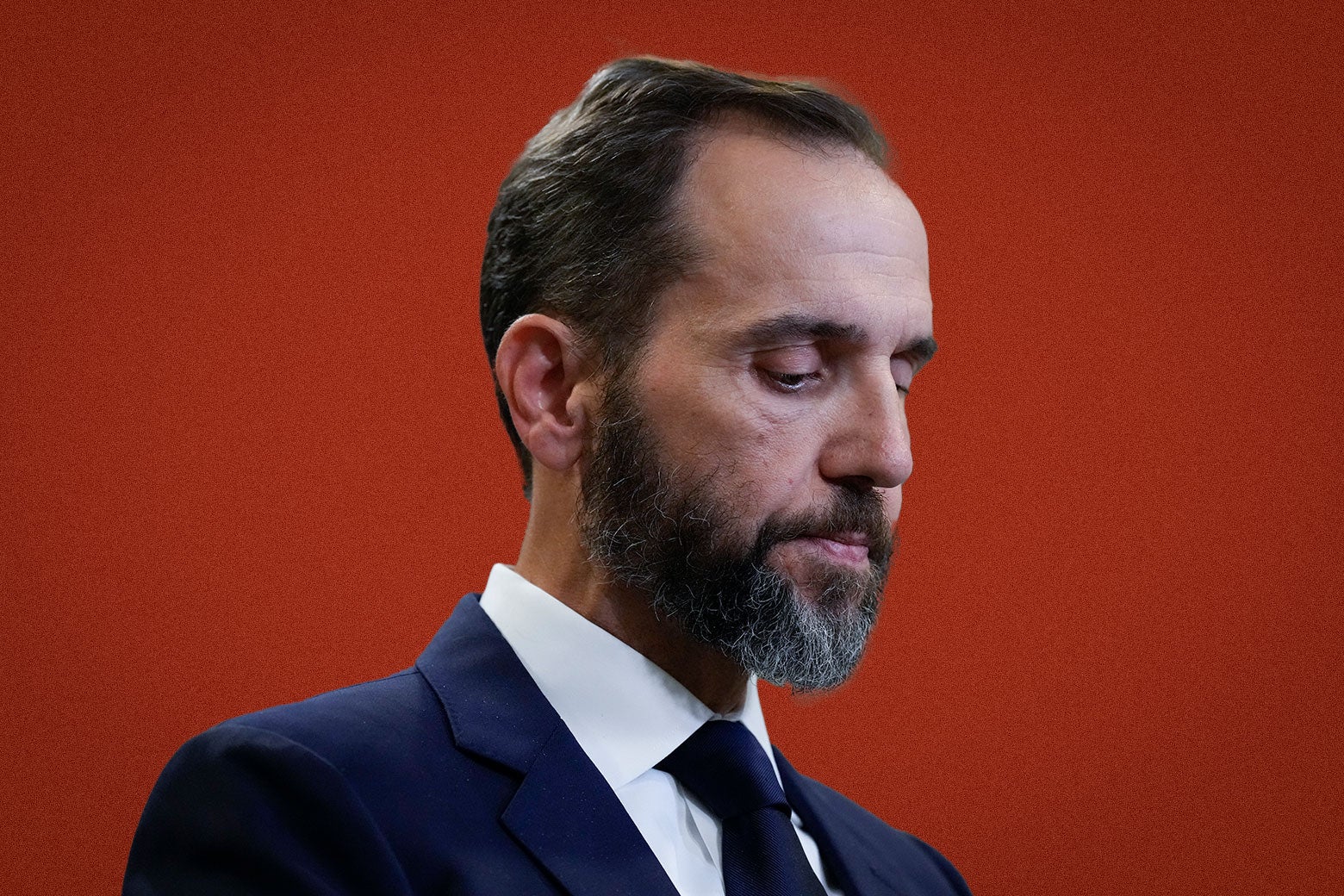

The six-page filing that special counsel Jack Smith submitted Monday is surely one of the strangest requests a federal prosecutor has ever had to make. Smith moved to dismiss charges against Donald Trump for election subversion, asking Judge Tanya Chutkan to toss out the case due to an “unprecedented circumstance”: The defendant has, of course, been reelected president. In the filing, he assures the judge (and the public) that the government “stands fully behind” the “gravity of the crimes charged,” “the merits of the prosecution,” and “the strength of the government’s proof.” The one teeny problem is that the defendant is about to reenter the office that he is accused of criminally abusing just four years ago (the exact subject of the doomed indictment). So, according to Smith, Trump is clearly guilty of multiple felonies—and constitutionally immune from prosecution for those felonies, in the view of the Justice Department.

It is not Smith’s fault that his investigation has reached such a premature and inglorious end. His hand was forced by a series of decisions outside his control, including the Supreme Court’s aggressive intervention in its immunity decision in July, which helped pave the defendant’s path back to the White House. Moreover, while Smith’s move is undoubtedly a surrender, it’s a tactical one that theoretically gives the special counsel time to produce a comprehensive public report detailing Trump’s alleged crimes. The filing even leaves the door open to restarting the prosecution after Trump leaves office, though it’s now nearly impossible to imagine 2029 Trump facing real consequences for his attempt to overturn the 2020 election.

None of this was inevitable: Shortly after Jan. 6, it felt eminently plausible, even likely, that the once and future president would face accountability for his misconduct. After the 2024 election, this notion seems almost laughable. As a practical matter, it is past time to put to bed the idea that no man is above the law. Trump is; who could deny it? The Supreme Court has put him there, depriving the public of a trial—which will now almost certainly never happen—a trial that could have placed Trump’s assault on democracy at the center of the election. As Rick Hasen explained in Slate, the court’s decision, in tandem with the election results, heightens the risk of criminal election subversion in the future, sending the message to aspiring autocrats down the road that they, too, can lawlessly obstruct democracy and get away with it.

Smith’s filing gestures toward these realities with more than a hint of incredulity about the novel situation. He is, he explained, irrevocably boxed in by a series of opinions issued by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, which provides advice to the executive branch. In 1973, the OLC declared that the prosecution of a sitting president would violate the Constitution’s separation of powers. In 2000, the office announced a “categorical rule” against the “indictment or prosecution” of a sitting president, asserting that criminal charges would burden the exercise of his constitutional duties. But neither opinion explained what should happen when a “private citizen” is indicted, and then elected president. The filing reveals that Smith posed this question to the OLC after Election Day, and the office responded that the case must “be dismissed before the defendant is inaugurated.”

The OLC did throw Smith one bone: It affirmed that the Constitution “does not require dismissal with prejudice,” which would preclude charging Trump again after his term is over “or he is otherwise removed from office by resignation or impeachment.” So at least in theory, Judge Chutkan can dismiss the case without prejudice, leaving the (vanishingly slim) possibility of a redo in four years. By that point, though, the statute of limitations will have long passed. A future court would thus have to “equitably toll” (that is, suspend) them, which is no guarantee. In short, the whole idea of a do-over is borderline fantastical. This case is dead. Not to mention that Donald Trump has suggested on more than one occasion that he intends to run for a third term, and he has surely proven beyond a reasonable doubt that even if he loses a future election he does not believe in the peaceful transfer of power. In short, the very conduct for which Trump will never stand trial is the conduct that may keep him from ever standing trial.

Where to place the blame? Attorney General Merrick Garland is partly at fault for waiting so long to commence the investigation into Jan. 6; his institutionalist instincts paralyzed the Justice Department for nearly two years, giving Trump a chance to run out the clock by the time Smith finally indicted him. Judge Aileen Cannon is guilty of sabotaging Smith’s other prosecution, over the theft of classified documents, a prosecution which should have been a slam-dunk. In a simplistic sense, the voting public also bears culpability for putting Trump back in the Oval Office despite his egregious attempts to steal the previous election. But that victory could not have happened without the Supreme Court, which essentially nullified the constitutional bar against insurrectionists returning to office, then awarded Trump sweeping immunity in Smith’s Jan. 6 case. The court’s immunity decision guaranteed that the former president would not face trial before the election, which in turn prevented the public from hearing the full range of evidence against him.

Perhaps the most stunning aspect of the Jack Smith filing is that if you squint at it just so, it reads not all that unlike the majority opinion in the Trump immunity case, as penned by Chief Justice John Roberts: It’s a dispassionate reading of the scope of presidential power and highlights the necessity that a sitting president be able to carry out his duties in a robust and fearless manner. Like Roberts’ reasoning in the immunity case, the Smith pleading is rooted more in institutional vibes than constitutional commands. After all, the “separation of powers” principles cited by the OLC were not written down in the Constitution—from which they’re entirely absent—but made up by lawyers seeking to grant more power to the president. Smith’s decision to adhere to the letter and spirit of the OLC guidance is … a choice, a norm, not a constitutional command. The need to punish criminality ultimately sags under the policy preference that a president be able to “fulfill his constitutionally contemplated leadership role” and the “constitutional interest in the President’s unfettered performance of his duties.” In both instances, the abstractions that animate this constitutional discussion about executive authority exist in a Trump-free vacuum. Here we have the courts and the Office of Legal Counsel in substantial agreement on a maximalist view of unfettered presidential power.

The lesson here seems to be that whether you are a Merrick Garland or a Pam Bondi, a Juan Merchan or an Aileen Cannon, a Jack Smith or a John Roberts, when the institutionalist rubber meets the temporal road, the Donald Trump character wins every single time. While one side doesn’t feel any compunction about ignoring the law, the other is hesitant to upend a nonbinding institutional norm. Lawlessness appears to be an agreed-upon outcome, a literal get-out-of-jail-free card, for whichever entity evinces the most contempt for the law.

With the American public having now witnessed an impeachment hearing, a Jan. 6 Select Committee investigation, and the real-time coverage of the events of Jan. 6, one can surely make the case that this Trump prosecution in federal court might have made little difference and that a final special counsel report on what might have someday been presented at that trial will make even less. But as we slog ever nearer to this vanishing point at which no consequences exist, we should be perfectly sober about which victories Trump seized for himself, and which were simply gifted to him.

Get the best of news and politics

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.