Intro. [Recording date: November 16, 2023.]

Russ Roberts: Today is November 16th, 2023, and my guest is journalist Haviv Rettig Gur. His last name is Gur, G-U-R. Haviv is a senior analyst for the English language newspaper at The Times of Israel. Haviv, welcome to EconTalk.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Hi, thanks for having me. It's good to be here.

0:57Russ Roberts: We have two topics for today. The first, we're going to take an historical look at European Jew-hatred, antisemitism, and the second is the current situation here in Israel as the war in Gaza enters its sixth week. And we'll see some of the ties between those two events.

Now, the first part of the conversation is based on a column we'll link to, you did back in April of this year, long before the war. And, it stuck with me. I thought about asking you to do an interview on it even before the war. That piece was called "The forgotten horrors that hide in the Holocaust's long, dark shadow."

And you begin by saying the Holocaust is thought of as this terrible, unique catastrophe for the Jews. And of course, that's true in some sense. But the genocidal uniqueness is a bit misleading. You write, quote:

... the 20th century was already among the bloodiest periods in Jewish history before the start of the genocide, that includes the flight of millions of Jews out of Europe and the way those who remained were delivered into the Nazi embrace by Western immigration quotas. It is a version of the story that begins not in 1939 or 1941, but in 1880.

Explain: Why do we need to go back to 1880?

Haviv Rettig Gur: It's a good question. There is a European Jewish experience of the 20th century; we'll call it the long 20th century from roughly 1881.

In 1881, a anarchist group, activist group assassinates the Czar of Russia. They had tried multiple times; they finally succeed. This is Czar Alexander I [should be Alexander II--Econlib Ed.], a profoundly reformist czar, a czar who had in the 1860s abolished serfdom and a czar who apparently on the morning of his assassination--he was assassinated in the afternoon--on the morning of, he gave the order to draw up some kind of a constitutional document ahead of the establishment of a serious parliament for the Russian Empire. He was a reformist who looked at Western Europe and said, 'I want Russia to be brought into the modern age.' But, for these anarchists that wasn't enough. They viewed these reforms as a way to preserve--with, I think, some justification, a way to preserve the prevailing social classes rather than abolish them and bring equality. And, they killed him. They managed to kill him. It was a clumsy thing, but it was ultimately successful.

Czar Alexander I [Alexander II] was replaced by his son, Alexander II [should be Alexander III--Econlib Ed.]. Now, his son was a very different kind of man, a very conservative one, educated on Russian Orthodox religious teachings, uninterested in the reforms--in fact, blamed the reformist impulses of his father for his father's ultimate death--and began a massive crackdown on everything that he came to view as enemies of the Russian Empire, reversed most of his father's reforms. He didn't reinstitute serfdom, but he did reverse many of his father's reforms.

Part of that was passing, a year later into his reign, of the May Laws. The May Laws were antisemitic laws passed by the czarist regime. It's a very short--I think on Wikipedia, people can find the 10 sentences or so that make up the May Laws--but essentially it further limited the already very strict limitations on where Jews can live and what employment they could pursue, and education, and essentially narrowed Jewish life.

But, another thing happened in the wake of the assassination of the Czar, and it was something that the Russian Empire didn't expect and didn't want. And it had a lot to do with industrialization, and it had a lot to do, especially with railroads and electrification of the empire. And, it mostly occurred in southern Russia--the Southern Russian Empire--and basically what is today Ukraine, cities like Odessa, and that was the beginning of mass popular pogroms. Started bottom-up where Jews and non-Jews lived together; and pogromists would march down the streets of cities in what would today be, I guess, Western Ukraine and attack Jewish homes, catch Jews in the streets, sometimes kill, often beat--really in 1881. And very, very quickly pogroms spread from one city to the next. And, there are these fascinating sociological studies of these early pogroms that they really did follow the rail network, and they were often spread by rail workers.

And so there was--it was an antisemitism that was, in some sense, driven by a lot of the industrializing changes that were happening to Russian society--the Russian Imperial society at the time--which included urbanization and the weakening economically of the peasant class that--you know, serfdom was abolished, but not everybody benefited from it in the same way.

There are all these complex and fascinating historical reasons for this sudden outburst, bottom-up of waves of pogroms that essentially would last at least 40 years. Over the next 40 years they would get steadily worse.

Some of these pogroms became very, very famous: the pogrom in 1903 in Kishinev. Every Jew knows the name Kishinev. Now they don't know the name Kishinev because they're familiar with, you know, modestly-sized towns in Moldova. They know the name Kishinev because in 1903, there was this pogrom, roughly 50 people were killed. Jews were killed in this pogrom. But, what caught the Jewish imagination and turned Kishinev into a rallying cry throughout the Jewish world, wasn't the 50 dead. It was how they died. It was the cruelty of the pogromists. It was the way that women were captured and raped in front of their husbands and fathers and brothers. It was the humiliation, the dehumanization, the emasculation of Jewish men. Hebrew poets like Hayim Nahman Bialik famously wrote about these men who carry the burden of that moment when they were forced to watch the rape and then murder, often, of their loved ones.

And so you had, in Kielce [Poland] and many other places, you had all throughout the Russian Empire, decade after decade, these bottom-up pogroms in many places.

Now, the Jews believed, because it came with the May Laws, because it came with this crackdown and reactionary political impulse of the new Czar, the Jews believed that this was a regime act: in other words that the regime instigated it. But, historians generally agree that that Jewish belief at the time is probably a mistake--a misunderstanding of the internal mechanisms of Russian politics and society around them. And that actually something much worse was happening, which is that it was genuine and authentic and popular and bottom-up. The people around them, around whom they had lived, really wanted them gone and really wanted them tortured and dehumanized until they understood the point.

And, in many places, the Czarist police actually saw the pogroms as a threat to public order and ultimately a threat to Imperial rule.

And so, there were attempts to crack down on these; and they were largely unsuccessful by the regime. In some places like Kishinev, for example, the global outcry, the Jewish outcry, which in places like the United States or Britain where you had influential Jews, that translated also into governmental outcry against Russia.

This caused the Russian Empire real diplomatic damage. And, Kishinev inspired the writing of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion by supporters of the regime--of the Russian Imperial regime--who couldn't understand why the world cared that Jews had died.

And so they saw this diplomatic blowback, and that really made them start to think in--or they'd already thought in conspiratorial terms of the Jews--but it made them want to explain it and create an anti-Jewish politics that was more explicit. Also to validate the pogroms themselves and to really create an intellectual--right?--level of this.

Russ Roberts: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion were attributed to the Jews, but were actually not written by the Jews. It was an alleged plan for worldwide domination that was used to incite hatred.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Right. Right. And, one of the justifications given at the time of their first publication--in Russian--was there's no other explanation for how the world cares about what happened in Kishinev. Right?

And so, these pogroms reshaped the Jewish world. Now they reshaped the Jewish world both mentally. They also reshaped the Jewish world demographically. They led to--oh, just one last point about the cost. These pogroms cost the Russian Empire a very great deal. The Jews began to leave Russian Imperial lands in their millions--probably 3 million over the course of 40 years. Of those 3 million--again, it's a rough estimate, give or take, a couple of hundred thousand, right? Of those three million, the vast majority, two and a half million, roughly went to America. And that is the demographic bulk of what is today American Jewry.

There had been German-Jewish, American-Jewish community beforehand, but the demographic bulk is actually that flight from Eastern Europe. Although the generation of Jews in New York that Mel Brooks makes fun of in his comedy career--the 2000-Year-Old Man, right?--those are his parents, who are these fleeing Jews.

The pogromist experience--the experience of the pogroms--hurt the Russian Empire because, as these Jews fled, many of them fled westward, but to the closest place they could, which was the Austro-Hungarian or the German Empires. And the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires were absolutely convinced that this was Russia trying to dump its Jewish problem on them.

And they were also fairly antisemitic. There were not the kinds of pogroms you had in Russia, but they didn't want these Jews. And, the diplomatic tension caused by these fleeing Jews, by these other empires who didn't want the Jews and were convinced this was a Russian intentional policy, actually led to the Russian Empire--which was in financial straits--losing credit lines with these other empires.

And so, the Jews were fleeing. The Russians were pushing them out. It was both top-down and bottom-up at the same time.

And that is the beginning of 60 years of the steady, not just emptying out of Europe of its Jews, but the conscious, willful, purposeful, systematic making of Europe uninhabitable to Jews. Literally uninhabitable.

And in different parts of Eastern Europe, it happened at different rates. Eventually it gets to Central Europe and then even Western Europe. It happens at different times. It happens in different ways. But, it happened, and it happened systematically.

In the 1920s, the Romanians kicked the Jews out of, or severely limit, Jewish access to higher education.

In 1938--this was one example I used in that essay because the Poles have a story they tell now about how Nazis killed Polish Jews--not Poles. And the truth is, of course, much, much more complex. In 1938, there were no Nazis in control of Poland. But Poland actually stripped Jews who hadn't lived in Poland--Polish Jews, who hadn't lived in Poland for the previous five years--passed a law stripping them of citizenship in order to ensure they don't come back. And, the Nazi Regime was so scared that they would be saddled with many tens of thousands--I'm not clear on exactly the number--of Polish Jews who are no longer Polish citizens, and so, they're stuck on German soil, that they rounded up 17,000 of these Jews and stuck them on the border with Poland, demanded the Poles take them back. The Poles refused. And, these Jews are actually stuck in a sort of miniature concentration camp in between these two countries with absolutely nowhere to go. No one rescues them. The Polish Deputy Ambassador to London says, if the West doesn't take them in, then their fate will be persecution until they flee. And, they're essentially there until they are murdered at the beginning of the war.

Russ Roberts: I think it's important: Listeners may not realize that the six million Jews in the Holocaust who were murdered between 1941 to 1945--some before that, but the bulk murder between 1941 and 1945--they weren't Germans. There weren't very many Jews in Germany. It's one of the stranger parts of this tragedy. They were Jews in Poland who weren't in those 17,000 who had been expelled, but hundreds and hundreds of thousands--I think over a million Jews in Poland--and the Jews in Russia who didn't leave in the aftermath of pogroms and persecution in the period 1880 to 1940.

You provide a remarkable set of facts that I had never been aware of. As you say, two and a half million of the three million Russian Jews come to America. As did many others. It wasn't just Jews who struggled with poverty and persecution and tough lives, and were looking for something better.

Obviously in this period of, say, 1880 to 1920, massive immigration into the United States from Ireland, from Italy, from Poland, Hungary, Russia, mostly Jews, but also non-Jews.

And, it's a shocking thing. You say that between 1908 and 1925, many of these immigrants to America decided they didn't like America so much. They're going to go back. 57% of Italians, 40% of Poles, 64% of Hungarians, 67% of Romanians, and 55% of Russians. Among the Jews, the figure was just 5%. And, your conclusion, you say the Jews stuck it out in America through thick and thin, prosperity and recession, other immigrants were seeking a better life. The Jews were running away. There was no better life than America, even when it wasn't so great compared to what they had left. And, I think that's really rather remarkable.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Absolutely. It's an astonishing data point because it tells the story. Right? In 1907, there was a crash. There was the Panic of 1907. That's why the data begins in 1908, this mass sort of wave of returnees.

The economy takes a dip. There aren't really jobs for people without good English, without family connections, without higher education. You can't really move up the social ladder in America in the immediate aftermath of 1907.

And there are these periodic market corrections that are quite painful, and there's, of course, no modern welfare state at the time, and all of that. And yeah: These immigrants say, 'This isn't working. We're sitting here on the Lower East Side starving, and so we're going back to Italy where at least we have a village, we have a farm, we have something.'

The non-Jews also came very differently, in a very different way. They sent young men first to establish themselves, find jobs, rent an apartment. Then the families came a year later, five years later, sometimes 10 years later.

And so, it was all done very comfortably. America was expanding and the American economy was expanding, and these people were coming in to help that expansion, and America welcomed them.

The Jews were running away. The Jews came as families. They landed in New York Harbor, by and large. Not every single time, but by and large as whole families. There was no one coming ahead of them. Jewish organizations were set up by the American Jewish community at the time, desperately trying to help these people land. I think the American Jewish community at the time--educated guess, I don't remember the exact numbers--but it's something like a quarter million Jews, mostly German speakers, many of them settled in the Midwest.

That's why to this day, you have a major reformed Jewish rabbinical school called Hebrew Union College. The central reformed rabbinical school in America is in Cincinnati, Ohio. Because in the mid-19th century, the Jewish immigration was part of the German-speaking immigration that settled in the Midwest. And, I think to this day, Germans are the second largest or maybe the third-largest minority in America. They're so big, they don't know they exist, is how big they are. Right? But, you have all these Midwestern cities with operas. Right? Milwaukee has an opera. St. Louis has an opera. Cincinnati, Ohio has an opera. That's this 19th century German immigration. And there was a large Jewish immigration then.

That middle class, formerly German-speaking, well-established, often Midwestern Jewish community is suddenly absorbing a wave of refugees over about 40 years that is five, seven, maybe 10 times its size. And, they're desperate and they're poor.

Russ Roberts: And now we come to the Holocaust. And you point out a much underappreciated or unknown fact--and I think this is true of authoritarian cruelty generally. To oppress a nation, whether it's Nazi Germany oppressing the Jews or the Soviet Union oppressing its own citizens in the name of protecting the power of the leaders, you need a lot of help. You can't do it on your own. Countries are large, generally. They have lots of territory to cover. A police state--another way to say it--a police state can't really thrive by having the police everywhere. They just can't be everywhere.

That's true, by the way--very true in China today or other places that have authoritarian impulses. They need help. They rely, crucially, tragically, on incentivizing everyday citizens to be part of the authoritarian state, the police state.

In the case of the Soviet Union, it's well-known, I recommend that all my listeners read the Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn or the Gulag by Anne Applebaum, one dramatically longer than the other. But, the Solzhenitsyn book has been abridged. I don't like abridgements--but the Gulag Archipelago has three volumes in it--but I think it's very much worth reading.

But, basically, you can't make a remark about Stalin that's negative because your neighbor overhearing it will profit. Will report you.

And so, the eyes of the actual police are extended by the bottom-up incentives that thrive in those kind of grotesque, cruel places.

And, the systematic murder of six million people--and others, of course, but the Jews were special in the zeal with which the Nazis sought them out--that required the cooperation of local citizens. At the same time, of course, Germany is prosecuting a world war on two fronts or more--really kind of three; I guess you could even say four. I mean, it's a World War. They're in a lot of places other than Asia--the Germans, the Nazis are. And, at the same time, they're running a massive campaign to systematically exterminate the Jews of Europe. And, they get a lot of help.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yes. There's one step we have to make before that step. And that is, of course, the end of the story, at least of European Jewry as it had been before. But, that last step is the quotas. The Jews are fleeing westward. The European nations are systematically closing themselves to the Jews, making their life literally untenable.

And then, in 1921, the United States Congress says--it passes something called the Emergency Quota Act. The Americans have been trying since 1910 to slow this Jewish immigration. But, the pressure on the Jews is only increasing to the point where there's this kind of intensity in the Russian Civil War in 1918 to 1921. The Mensheviks, the Bolsheviks, right?, the White Russians, the Red Russians, the Ukrainian nationalists--all these different armies, all these different forces in this very chaotic civil war come across Jewish villages, massacre Jews. Estimates are hard to come by. I have read pretty good estimates at 100,000. There are estimates estimating 150,000 and above murdered Jews who were not part of any of these armies.

And so, the intensity of the violence and the brutality is still increasing in the early 1920s.

In 1921 alone, well over 120,000 Jews, just in 1921, land in New York Harbor.

And, Congress decides to act. And it passes the Emergency Quota Act, which it imposes quotas by nationality. The Jews have no nationality in the American definition at the time. They're either Poles or Russians or something like that. But, it is engineered to make sure that Jews don't come. And, it works. Three years later when they pass the full Quota Act, the Permanent Quota Act, it's down from about 120,000 to 140,000 a year, down to 10,000 a year.

And, by 1934, after the 1924 Act really goes into effect and there's a few more tweaking of the system, just 2,700 make it into America that year. And, the Nazis are already in power, of course, by then.

So, as the urgency for the Jews escalates, the West closes its doors. It's not just America. It's Canada. It's Britain. It's France. It's Argentina. It's Brazil. It's Australia. Everywhere Jews could go shuts down to them. And that corrals them essentially into the Holocaust.

Russ Roberts: And we'll talk, in another episode down the road, about what was happening with Zionism during this period: the desire for a Jewish state, a Jewish homeland. It's intensified by the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903 that you mentioned earlier, which occurs roughly five years after the beginnings of Zionism as an organized movement. Jews have longed to return to Israel for 2000 years, but in 1897, as the pogroms that you're talking about start to get fiercer, as European nations become increasingly inhospitable to Jews, and then later as these pogroms become much more murderous, the Jewish population around the world is desperately looking for an asylum, a haven, a place of safety. And, it's a combination of security desires with a religious yearning that has been there for 2000 years. But, obviously as we know, that doesn't happen until 1948.

So, in this run up between the reduction of immigration opportunities, the closing of America and elsewhere, the Jews of Europe find themselves stuck. And, the part that's, I think, particularly interesting about your essay is that effectiveness--the tragic effectiveness--of the German efforts to exterminate the Jews of Europe depends very much on how much help they get from the places where the Jews live. And, as you mentioned in passing--I think it's a half a sentence--it's been very hard for Europe to cope with this. Germany had to cope with it. They have faced it in very many--overwhelmingly, in my view--in admirable ways as best as they could.

But, many other nations pretended or just decided not to think about the role they had played in the Holocaust. Different European nations at different times have been forced to--not forced--but have come to grips with this in different ways, some more than others. Again, that's a whole 'nother conversation. But just the point about the more cooperation the Nazis got from their neighbors, the more Jews were killed.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah. You know what I would like to focus on. I would like to frame everything that we're discussing here as the Jewish experience. Because the Jewish experience is very different from the experience from the moral--Western moral discussion of the Holocaust. The Western moral discussion of the Holocaust is--some of it, by the way, informed by American Jews--is a discussion of the Holocaust that tries to find the sort of psychological-political, psycho-political origins in which the lesson of the Holocaust is: Don't be chauvinist. The lesson of the Holocaust is: Don't be ethno-nationalist beyond, you know--what did Woody Allen say about antisemitism--more than is absolutely necessary. Right? In other words, a kind of pro-liberal, relaxed, tolerant ethos. That is the great lesson of the Holocaust.

But, that's not a lesson drawn by the people who experienced the Holocaust. That is a lesson drawn by outsiders who need the Holocaust to have some kind of easy moral lesson that validates themselves.

And, the actual experience of the actual Jews created new kinds of Jews. I'm not just talking right now about Zionism. It created new kinds of Haredi Jews. It created new kinds of, the entirety--

Russ Roberts: Ultra, Haredi being ultra-orthodox. Keep going.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Right. You're absolutely right.

The Nazis planned and perpetrated the genocide. They were not successful in the places where locals didn't help. Place after place--and it's not just that there were countries where the locals didn't help, like Denmark--where the Nazis simply were not able to kill the Jews. It's down to inside countries.

One great example is Hungary. The Hungarian government in 1944 joined in this Nazi effort to destroy the Jews. The Nazis asked for the Jews and the Hungarians put about 430,000 Jews on trains and shipped them off to Auschwitz.

But, they were all Yiddish speakers from the provinces. They were all rural Jews. The middle class Budapest Jews were not shipped off to Auschwitz, because that seemed--that felt--to the government of Hungary, horrifying and a kind of culpability that it didn't want to face. And so the Jew that it was uncomfortable to kill because they look too much like us, survives the war. The Jews of Budapest survive the war in Hungary. And the Jews of the provinces, the Yiddish speakers, the Hasids, all of those different cultures don't survive.

In fact, that's the story of the Holocaust. The Jews who were murdered, something above 80% of them, were Yiddish-speaking Jews.

And you see this in Athens: the Jews of Salonica, the Greeks shipped off very happily. The Jews of Athens, they didn't, and they refused when the Nazis asked for them because that--

Russ Roberts: [inaudible 00:29:36].

Haviv Rettig Gur: was a kind of--yeah?

Russ Roberts: Just to be clear to listeners, when you say they were Yiddish speaking, meaning they didn't naturally assimilate into the culture that they were living in. They lived apart. They had--

Haviv Rettig Gur: Right. The Jews of Budapest were--

Russ Roberts: They might have lived in ghettos. Say again?

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah. The Jews of Budapest were these educated, Westernized--they wore suits, they were lawyers, they were doctors, they were physicists. And then, there were these rural, much more religious, Hasidic-looking--right?--Jews of the provinces who spoke Yiddish, did not have that modern Western education. They were the ones targeted.

And so, the point here isn't that--to get to the sort of meat-and-potatoes of how the Hungarians tried to--they needed the social distance to be able to massacre, to be able to ship them off for the Nazis to massacre.

The point is, that where the Hungarians were uncomfortable, the Nazis were unable to do the job. And so, the fact that the Nazis were able to do the job in 90% of places means that the Nazis did it, planned it, they deserve every--we need to know that this is a German act.

But, we also need to understand that it is the culmination of six decades of a Europe-wide cultural, political, psychosocial--give me all the words they love cooking up in academia--it is a Europe-wide cultural phenomenon for six decades.

The Holocaust is its apotheosis, is its culmination. It is what it was directed toward. It is not an aberration. It didn't begin in 1939. And, to understand it, or I don't know what the sort of massive uptick in gas chambers in 1942 with the Final Solution decision, or 1943. It begins in 1881. And, it begins with European, country after country, determining, sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, sometimes openly, sometimes quietly, that it's simply they don't want to contain the Jews.

And, I want to just--one last point, everybody knows about the Holocaust. Maybe they don't realize how much collaboration there was, but everybody knows about it.

But after the Holocaust, the fundamental story in the Jewish experience doesn't change. The Jews after the Holocaust, those quotas are not lifted. Truman begs Congress to lift the quotas because after the war, the United States military finds itself on German soil with 250,000 Jews behind barbed wire in a whole network of displaced persons camps. And they're feeding them, and they are taking care of them. And it's expensive, it's annoying, and they can't get them out.

There were about a million displaced people about eight months after the War. In the immediate aftermath of the war there were probably 15 million or something like that. A lot of people go home, find a way, they get home.

But, there's a million who are unable to get home. Huge numbers, the majority, because there were Nazi collaborators in places now overrun by the Red Army, and if they go home, they die. This is true in Ukraine, in the Baltic States, and other places.

Some of them are Polish Catholics. Poland is descending into a kind of civil war in the immediate aftermath of the war. Long story short, there's about a million displaced peoples in Europe, probably a quarter of them Jews.

And, the United States and Britain found something called the International Refugee Organization, which has roughly 40 countries, give or take three dozen countries, who are members of it. And, they send representatives to these camps and they interview these DPs [Displaced Persons]. And they want these people to come to their countries. These are from Latin America, from North America, from the West, to help rebuild the economies shattered by the war. Everybody needs working hands. Tens of millions of workers have just been killed--right?--in these wars.

And so, they come to the camps, they interview the DPs, and they take, in 1946, 750,000 DPs who are naturalized and absorbed into their new homes.

Russ Roberts: DPs meaning, being Displaced Persons.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Right.

Russ Roberts: What we would call refugees, but at the time they were called DPs, DP camps for these folks.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Right. And, they are trapped.

Now, what is a DP? A DP is someone with nowhere to go, either because they'll be killed if they go there so they refuse, or because nobody will take them. And, so, they're literally not allowed to leave the DP camp. The DPs are behind barbed wire, and that barbed wire is patrolled by British or American, depending on the zone, troops. And, many of the DP camps are the concentration camps.

So, for example, Bergen-Belsen is liberated as the allies march eastward through Germany. Unless you were an actual inmate of Bergen-Belsen, because you still couldn't leave two years later. So, were you liberated?

I don't want to take away from the Americans and the British the fact that the extermination was stopped. That is not a small thing, obviously. But, the Jew in Bergen-Belsen is still in Bergen-Belsen in 1947. That is not what liberation looks like, and there are a quarter million of them.

And, Truman asks Congress to lift the quotas. Congress refuses. Again and again, 1945, 1946, 1947. Jewish groups beg Congress to do so in America. Christian groups come to Congress and beg Congress to lift the quotas. We're not talking about millions more Jews. There aren't millions more Jews. We're talking about these last vestiges of a decimated Jewish world. And nobody will take them in.

When do the DP camps empty out? They empty out essentially the founding of Israel in 1948. So much so, that a huge proportion of the Israeli military in 1948 that fights that war of Israel's Independence--probably a quarter--were DPs.

Their experience of that war, their experience of this is new Israel.

Leave aside ideologies: we're not talking anything--nothing we have talked about here is ideologies. What's fascinating to me is not what tiny ideological elites, how they tell the story of what happened to their peoples. What fascinates me is to just literally trace the experience of the actual people themselves living through these periods. What does it mean for an IDF [Israel Defense Force] soldier to be an IDF soldier after three years in Bergen-Belsen? After Holocaust? After knowing that his parents and grandparents lived through six decades of what we just described? That's the founding of Israel.

Russ Roberts: IDF being the Israel Defense Force, which is the Israeli Army.

36:22Russ Roberts: Of course, Israel was established in hopes of a very different culture. But, if we go back to 1903 and Bialik's poem that you mentioned earlier, that poem was about the cowering of the men you discussed in the face of violence to their wives and daughters. It's a brutal poem. The Holocaust, yes, there were uprisings in Warsaw and elsewhere, but in general, the Jews of Europe were passive victims. I don't think they went to sheep-like slaughter, which is one of the canards that describes that experience, but it's not far off. You can argue with it--Jews got on the trains to the concentration camps in ignorance of what awaited them, and I think that was true for quite a while. The Nazis were very secretive about what was actually happening. They were called 'concentration camps,' remember, places where people were concentrated. Meaning, they were taken away; they weren't going to be in the cities and towns and farms of the country, they would be concentrated, like a ghetto.

And these camps--you know, people took suitcases. Thinking they were going to have lives in these places for some time.

Finally some people escaped and said they are death camps. But, a lot of people didn't believe them--and reasonably so. What do you mean? You mean the German people, the people of the great artists and composers and philosophers of the last 300, 500 years, they're systematically murdering people? I mean, it's literally not credible.

So, there was a great deal of skepticism. So, a lot of people went to their deaths not thinking they were going to their deaths. They thought they were going to a persecution or a different kind of savagery than they had faced at home. But ultimately it came to be known.

But the point is, is that the Jews were murdered in a systematic way without much opposition. And, when Israel was established in 1948 and when Arab countries, unhappy and dissatisfied with the U.N. [United Nations] Partition Plan of 1947 that we discussed in a recent episode with Yossi Klein Halevi, they were going to fight.

And they did. They were grossly outnumbered, grossly under-equipped. Their air force was literally a handful of Czech--and broken Czech planes that, Czech from Czechoslovakia--and a few others. It's an extraordinary story.

But, the point that you're making is, and I think it's, again, it's one that I did not appreciate, is that the period between 1945--the liberation of the concentration camps, the defeat of the Nazis and the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948--was not a happy time for the people who mercifully survived.

There were--in fact, some people went back to Poland and there were pogroms in Poland. Again, a pogrom is when a mob assembles and decides to destroy property and lives and wreak havoc with Jews. There were pogroms in Poland after the war. And this is just, again, not well-known. It's horrifying.

Haviv Rettig Gur: It's really extraordinary. Truman actually had a representative who was the dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School. I believe his name was Harrison--we can look that up--but who Truman sent to the DP camps. And he couldn't get Congress to lift the quotas, so he wanted to find other solutions for the Jews. And, Harrison gave this surveys in one camp where he asked the Jews to essentially pray[?] art, write a list of the places they want to go to so at least we know where they want, and maybe that's part of the beginning of a conversation about a solution. And, he said, 'Rank for me the five places you want to go from most to least.' And, it was something like 90% wrote on the first line, Palestine, and then 90% wrote on the second line Palestine.

And, Harrison was annoyed, because apparently Jews don't understand what surveys are.

And so, he gave a new one where he said, if not Palestine, where would you go? And, 20% in this camp wrote gas chambers--or the crematorium, I think is what they wrote.

In other words, if you want talk about Zionism, not as an ideological construct that we in our modern cleverness and in our clever, modern academia need to deconstruct, which is absolutely the function of academia and have at it. But, you want to talk about Zionism as a lived experience. Zionism begins 1897, right, when the first Zionist Congress meets with Herzl.

Well, who is Herzl? What actually is Zionism? I have a bit of a cantankerous view on what Zionism is.

There are all these idealistic Zionisms. There's the [foreign language 00:42:04], who is one particular thinker from Southern Ukraine, particular time, and he talks about a cultural kind of Zionism where the land of Israel becomes this cultural center of Jews. And, we don't even need a state necessarily. We need to be a light onto the nations by our cultural production.

And then, you have religious Zionists who talk about a Messianic age. And, you have communist Zionists, which is one of the main, really, streams of Zionism who have that idealism.

And then, you have British aristocratic Zionists, and you have American Jewish Zionists.

And you have all these different Zionists. And literally all of them meet at the casino next to the train station of Basel in 1897 for the first Zionist Congress. Herzl chose Basel because it was a train hub. And so, it was easy for all these very disparate groups to meet. And, it just tells you that the kind of diversity of Jews and of Jewish ideals and ideas and cultures that rallied around this Zionist flag.

Well, if all of these things are Zionisms, what the heck is actual Zionism? What unites them? What unites a religious Messianic Jew and a communist, atheist? What is the unification? And, the unifying principle is--and the reason Herzl is Herzl--is this sort of visionary faces in every classroom in Israel. The reason Herzl manages to unite all these people, is that Herzl delivers what is Zionism's heart and soul.

And, it is not a nationalist identity. It is not a narrative of historical belonging. It is these things--these things are part of Zionism. But the heart of Herzl is a strategic argument.

And it's the argument that I'm going to obviously paraphrase and translate to modern times. But, it is the argument that Europe is undergoing profound social changes and those profound social changes of industrialization, urbanization--people are detaching from old identities and producing new identities. You are no longer from some tribe in Bavaria where you know all 200 people that you live with from some village, right? You are now something called a German. And, because of the economic changes are happening and industrialization, the very pressures that create communism in the 19th century, they create new mass societies, new identities, where suddenly you are something called a German, and there's millions of other Germans, you've never met them, but somehow you and they share this fated bond, and these new identities are forming that are essentially imagined communities.

I mean, right? That's not saying they're bad or wrong or don't exist, some of the most important things in our lives are imagined. We're a creature that can imagine a great deal of institutions and states and money, etc. All things, legal[?], all imagined. But, these new imagined communities are forming that Herzl warns: They will police their boundaries, they will police their membranes. To be German--I'm going to take the extreme example, which is Adolf Hitler--and just because the extreme is clarifying, but many, many other nationalisms had some version of this less than Hitler. But, why did Hitler hate the Jews? Why did Hitler hate the Jews more than he hated groups that in the Nazi racial hierarchy are lower than the Jews? He had a whole sophisticated complex racial hierarchy. Why did he hate Jews more than Africans? Why did he hate Jews more than Southeast Asians?

And, his answer was essentially, this is obviously my paraphrase, but folks read Mein Kampf. His answer essentially was people like Albert Einstein. Albert Einstein, who comes from Germany--who had Swiss citizenship, but he comes from, I think the city of Ulm--Albert Einstein was a German in the morning and then a Jew in the afternoon. He was the great physicist of the German-speaking world, changed the whole world, created modern science, and then flew to or took a boat to Jerusalem to found the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. As a Jew.

And so, for someone like Hitler who, for the Nazis who argued that German-ness--this thing we just made up in our imperial struggle against the French--and for some reason the Austrians maybe aren't entirely in it, but kind of are, different depending on your politics--this thing called German-ness actually is ancient and organic. And, it's this tribe that came out of the dark forest, and it has this old nobility to it, and it is blood.

People arguing that, for the Jew to be able to be inside German-ness and then outside German-ness perforates that membrane.

And so, the Jew, by their very existence--by their capacity to have layered identities--are a threat to German-ness itself, something that no African could be. And so the Jew had to be exterminated.

Herzl thought in 1890s, predicts, not the Holocaust. He spoke of the coming catastrophe. He probably was thinking something along the lines of the Russian Civil War that we talked about. Nowhere does he show that he thinks it's going to be literally a holocaust of that scale. But he predicts that identity anxiety, that identity quandary that drives that antisemitism.

And, that itself is the organizing principle of Zionism. It is a simple principle. If you don't get out, a catastrophe is coming. You want to be Communist, you want to be religious, you want to be American liberal, whatever you want to be, but get everybody out. And, he says, even: the Jews are going to discover this 10 minutes too late.

And, at one point he says, I don't know if it's going to be expropriation from below, by which he means Marxist, or if it's going to be reactionary confiscation from above: 'I don't know if they're going to kill us, murder us, or expel us. I suspect it'll be all these things at once.' That's a quote that he records in his diary after a meeting with the Rothchilds: 'This is what I told the Rothchilds.' It was a fundraising meeting, so maybe he went a little over. But, wow, what predictive power: Zionism warned.

Russ Roberts: This is 1902?--

Haviv Rettig Gur: I think it's late 1890s.

Russ Roberts: Okay.

Haviv Rettig Gur: I have to look up the exact quote, but I have it written down somewhere. But--

Russ Roberts: My point is it's not 1931.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yes. No, I think he passes in 1904.

The Zionist movement is founded on this idea--the organizing idea--that over the next 45, 50 years after Herzl, Europe just proves, Europe literally just lives out the Zionist warning. And so, when Herzl gathers together the Jews in 1897, he represents a small minority of Jews. Zionism is not attractive. It's more attractive the closer you are to the pogroms. So, it's quite attractive in the Russian-speaking East. It's not at all attractive to most Jews in Vienna, where Herzel lives. He went to the opera one evening and the Jews at the opera publicly and openly, and in a crowd, mocked him. And, he records this: mocked him and said, 'Here comes the king of the Jews.' A man who thinks he's going to now redeem the Jews and found the Jewish kingdom. And, they're mocking him. And then, all of these predictions just come to fruition.

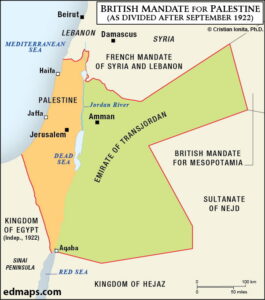

Russ Roberts: So, I want to bring us back to the DP camps and that survey. It's important to note--I think I may have done this in the Yossi Klein Halevi episode--but it's important to note this because it's a mistake that is commonly made. There is no country called Palestine in world history. There is a landscape, an area called Palestine, that in 1945 in those DP camps, or 1946 or 1947, whenever Truman sent that representative, Palestine meant the land that the British controlled in the aftermath of World War I. They get it in the aftermath of World War I from the Ottoman Empire. So, there is no country called Palestine, there's a place, and it becomes the place in the Zionist movement. It takes a while, but eventually that's where the Zionist movement that begins formally as a political movement in 1897: It becomes focused very soon after that, with some stops and starts, on Palestine, the area under control of the Ottomans at the time in 190-whenever. But then, after World War I, starting in 1919, 1918, at the end of World War I, it becomes British.

So in 1945, 1946, 1947, when Jews who had lived in Poland and Russia and Germany and who were Hungary and [?Hungarian?] descent there were still any left, or Italy or France, they wanted to go to Palestine. The problem was they couldn't get in. The British, just like the United States, in 1921 would not let them in. They could not go there. There was no Jewish state and the state that was there, what was called the British Mandate--meaning a territory governed by British rule--did not want to take in Jews, partly--well, for a lot of reasons.

But, Britain was trying to--as we started to talk, I think talked a little bit about, in the Yossi Klein Halevi episode--Britain's got a little problem. They have an indigenous Arab population in Palestine that they had promised some national hopes and aspirations, to meet those, if they aligned with them against the Turks, which they did in World War I. And those people were still waiting--1946, 1947--for the British to keep that promise.

At the same time, there was another indigenous population, the Jews: smaller, but very, very eager to have their own land through 1917 and was called the Balfour Declaration. And, the 19--is it 1925 or 1935?--the Peel Commission, England is showing lots of signs of meeting Jewish national aspiration, but they will not do it.

And that brings us to the aftermath of World War II, when Jews have no place to go. And, as much as they might want to go to Palestine, they can't.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah, the British in 1939 issued something they call the White Paper. 1939, because of the three-year Arab Revolt, which is suppressed brutally by Britain. Their estimates that 10% of the young men, of the fighting age men, of the Palestinian-Arab population probably were either killed or expelled in that British repression of the Arab Revolt.

But, it also flips Britain to the Arab side. In other words, Britain then says, 'Okay, Palestine is not a solution for the Jews,' which Britain had said that partly because some of British leadership was devout, sort of Zionist Christian, and also because they didn't want Jews ending up in Britain and the Jews were on the run. And so: 'If we don't find a solution for them, they'll all come here.' Britain pushed for a Jewish State of Israel, pushed for--it supported the Zionist movement, often for anti-Semitic reasons as much as for actual Zionist reasons.

All of that is true. The ordinary experience of ordinary Jews, which is--again, I think the driving force of history is the ordinary experience of ordinary people; I'm interested in the ordinary experience of ordinary Arabs in this time; I'm interested in the ordinary experience of ordinary Jews in this time--was that as all of the gates are closing, the last gate closed in 1939. And that was the British Empire literally on the eve of World War II telling the Jews: Even this last vestige, this Zionist hope, even this we're taking away from you. That's how the Jews remember the British. And so, when you essentially--is the last closed door, funneling them into the gas chambers, which is the correct way to remember the British if you went through the gas chambers. Right?

With all due respect to now--everybody will try and say, 'Yes, well, how could the British have known?' etc., etc. If you didn't know this history that we've just described here, you didn't care. You weren't paying attention. It was more important to you that the Jews not land in Britain than whether they live or die. And so, that's our memory of that period.

In a weird way, that really does bring us to right now. That brings us to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a profound and immediate way. Because, this story of the Jews isn't the American-Jewish story. It's not the story of the Jewish history as told by English-speaking Jews. For the simple reason that: Who are American Jews? They're the Jews who make it into America before 1921 and don't go through the 20th century that we just described. And, who are the Israeli Jews? They're the Jews who do go through that history, because they're the ones who couldn't get into America or the West generally after 1921. And so, they include the Jews of Europe who literally couldn't move westward, and they include the Jews in the immediate aftermath of the founding of Israel in 1948.

That same energy, that same mass expulsion, mass flight of all the Jews from the East, the uninhabitability of two Jews that sweeps through Europe, that begins to sweep through the Arab and Muslim worlds.

And you suddenly see hundreds and hundreds of thousands of Jews--probably as many as 800,000 in about four years--landing in Israel, almost the entirety of the Jewish community of Iraq. Baghdad in 1930, I believe is about 25% Jewish. That's about double the rate of New York City. Baghdad 22 years later is 0% Jewish. No Jew could remain. Anti-Zionist, Iraqi, nationalist Jews all fled. And, over the course of the 1950s and into the 1960s a little bit, the Jews of North Africa completely empty out, some to France, most to Israel. And that's true of the Jews of Yemen and the Jews of Syria and the Jews of Egypt.

And, Israel--suddenly its Jewish population of about 700,000 and its founding at the Declaration of Independence becomes 1.3 million Jews within four years. And so, Israel becomes the only place you can leave. And, the only reason the Jews in the Arab world didn't experience what the Jews of Europe experienced, if not a Holocaust itself--because what state in the Middle East would have been competent enough to produce a Holocaust on an industrial Nazi level at that time? But, certainly everything leading up to the Holocaust. The reason the Jews didn't experience that was simply because they have somewhere to go to. And that was the big difference.

And so, the Jews of Israel--I have an argument to Palestinians; and I engage with Palestinians constantly, and I try to make this argument. And I'm usually shut down or ignored, for reasons that I think are absolutely fascinating in themselves. But, my argument to Palestinians is that: the strategy that Palestinians have pursued--anti-colonial terrorism, anti-colonial violence--it's a strategy modeled on other anti-colonial conflicts.

Russ Roberts: Including, it's important to note, the Jewish response to the British here in Palestine. Between 1945 and 1948, the Jews viewed, strangely enough, the British as the colonialists. They have a long history of that and the Jews--so, many who had lived here for centuries, a small group; and many who had been able to fight their way here through those closed gates, which a few did--they made life miserable for the British. And the British finally in 1948 said, 'We've had enough. We wipe our hands.' UN [United Nations], in 1947, they said to the UN, 'You fix this.' They dropped the partition we talked about with Yossi Klein Halevi, 55% to the Jews, 45% to the indigenous Arabs here.

But, the 55%--the Jews--gets mostly desert. It's not very attractive. But, either way, the Jews were happy to take it.

The Arabs said, 'No, we don't want any Jews near us or any Jews on this land.' And, they instead launched the invasion of the country.

That brings us to the anti-colonial terrorism that has run through, tragically, I think for both Israelis and Palestinians for the last 70 years, whatever you want to call it. So, talk--go ahead, continue.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah, I mean, the colonialist paradigm is arguably one of the founding concepts of that Palestinian-Arab identity. In other words, from the 1910s--from 1914 and 1908 with the young Turkish Revolution that ousts the Sultan in the Ottoman Empire--the Imperial censorship is lifted; and suddenly Arabs all over the Arab world under Ottoman rule have a free press for some period of time.

And, what you end up seeing is that they found these newspapers and begin talking out loud; and you suddenly discover that they are concerned with Jewish immigration. Now, Jewish immigration in 1914 is minuscule. It's a few tens of thousands of people. It's not massive. It's not endangering them; but they understand it in the framework of a larger context.

So, during the Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire is the Ottoman Empire's greatest threat. They fought four major wars, including wars in the 1880s that were conquered wars; the Russians conquered large parts of the Balkans from the Ottomans very, very recently. And, Arab elites in Jerusalem, in Beirut, in Haifa, in these cities and towns of this region, saw themselves as Ottoman elites. They saw themselves as--the Ottoman Empire had ruled here for 400 years. There had never been any other political order in living memory.

And so, they understood these Russian-speaking Jews not as refugees fleeing the Russian Empire, but they spoke of them as agents of the Czar--agents of the Czarist regime. When Jews begin to flee other parts of Europe, they think in these--they try to frame these Jewish arrivals as Imperial arrivals.

The numbers start ticking up after the early 1920s when the doors closed to the West, ticking up dramatically. I mean, in the first 40 years after 1881, when two and a half million Jews go to America, maybe 50,000 total over 40 years went to the land of Israel, all told.

The Zionist movement was a minority view among Jews, right up until it wasn't. When wasn't it? In 1935 alone, just that one year, sixty-five thousand German-speaking Jews arrived in Israel. And so, they're refugees, right? That's the point. They are fleeing.

But, whenever they flee, there was a big debate among the Jews. They had founded this technical college called the Technion--in the 1920s, I believe--which is today Israel's MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. It's the finest technological school in Israel. And, there was a big debate over whether it would teach in German [Russ accidentally said "Yiddish," but this should have been "German"--corrected at Russ's request.] or whether it would teach in Hebrew. And, the reason there was a debate was that Hebrew was a religious language. It was spoken; it was known. Rabbis could write letters to each other across different cultural gaps and linguistic worlds in Hebrew, but it was limited essentially to religion. It didn't have a vocabulary. It was about 80,000 words, all told. It didn't have a vocabulary for discussing quantum physics.

And so, if you're going to found the Technion and it spoke Hebrew, you'd need new Hebrew words for quantum physics, right? And, the decision was made to go with Hebrew.

Now, Palestinian-Arabic press followed that debate among the Jews. How did it follow that debate among the Jews? Palestinians discussed whether the Jews, if they chose the Germanic Yiddish, then the German-ness and the German Nationalism and the German Imperial cause that really secretly sent all these German-speaking Jews here was winning out. And, if they went with Hebrew, then there's Hebrew Nationalist causes winning.

In other words, they looked at us and imposed on us--for a century, now--all kinds of intellectual models that made sense to their experience and that made sense to their experience of us, but had nothing to do with our actual experience.

And that has been going on for a hundred years. So, if you want to understand the October 7th massacre by Hamas of 1200 Israelis in such a brutal way, you need to understand the model that Hamas is using to understand us. And, that model is Algeria.

In 1962, after eight horrific years of a horrifying terrorist war by the National Liberation Front [FLN] of Algeria, against the French. It is absolutely critical to say the French army in that war was even more brutal than the FLN fighters. In other words, they probably killed 400,000 or 500,000 Algerian civilians. And, that's what historians think. The Algerian sort of national story has a number that's even higher than that. Horrific war by both sides. And, the war was successful. The French had begun to settle Algeria in the 1830s. By 1954, the French had been there for about 120 years, and there were a million and a half white French Europeans there.

Algeria was declared a Departement of the French Republic. It was part of France. It sent representatives to the French Parliament in Paris.

But, even though it was this Department of the French Republic, France never extended citizenship to the five or 6 million Algerian Muslims living in Algeria.

And so, in 1954, the Algerian Muslim civil society organizations or various political groups get together and form this unified National Liberation Front that launches this horrific terror war. And after eight years, in 1962, a miracle happens. The French just get up and leave. This tremendous--it really overthrows French politics. It brings de Gaulle to power. The Algeria War, it's this momentous time, not just in Algerian history, but in French history. But it works. Every French diplomat, every French bureaucrat, every French soldier, every French man, woman, and child gets on a boat back to France. That's 1962.

In 1964, drawing from that experience, the Palestinian political factions get together in a room and form the Palestine Liberation Organization [PLO], modeled on the National Liberation Front.

Anti-colonial conflicts, anti-colonial struggles, basically share one--the violent ones--basically share one sort of strategic paradigm. And the strategic paradigm is very, very simple. The colonialist shows up in your country for some benefit that they perceive. Give that benefit the value of X. How do you get rid of them? You create a cost that is higher than X. And now, again: that the colonialist perceives to be higher than X. We're talking about hacking the colonialist psychology. The higher the cost--if it's X plus one, they'll eventually leave. If it's X plus 300, they'll leave very quickly.

And so, anti-colonial struggles, by their basic logic, tend to horrific cruelty, tend to terrorism. Not because colonized peoples are more cruel than anybody else, but because that is the basic founding logic of anti-colonial struggles; and it worked everywhere. It worked everywhere it was tried in the 20th century.

And so, the Palestinians look at the Jews of Israel in 1964, and they say, 'Well, they've been here a long time. The French were there a long time. There are many of them. There were many French.' And they launch this conflict.

Now, they'd already been talking about a colonialist/anti-colonialist conflict in the 1930s, the Great Arab Revolt in 1929. Even in 1920, there was an organized Palestinian massacre of Jews. But, it becomes systematized and ideologized in the 1960s, under Yasser Arafat in the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization]. The generations that grew up in that paradigm.

By the way, the connection is profound. In 1974, Arafat gives a speech of the U.N. General Assembly. Who introduces him to the podium? The President of the Assembly, who was also the President of Algeria, who was also a leader in the FLN.

In 1988, the Palestinians issue--Arafat issues--a Palestinian Declaration of Independence. By the way, on November 15th, 1988, Yasser Arafat declares independence of the State of Palestine. Where does he do it? In Algiers. Palestinian school children learn the Algerian experience. And that drives decades of terrorism: of raids across the border, of mass murders, of shooting up school buses of Israeli children, of the Second Intifada, 140 bombings of the airplane hijackings, and also ultimately--

Russ Roberts: The murder of the 1972 Israeli Olympians--

Haviv Rettig Gur: Yeah, absolutely: the 1972 Munich massacre, the Olympic Massacre.

And the October 7th, 2023, just rampage. Horrific, brutal rampage.

If you're Hamas and you have the chance to murder Israeli civilians, why would you do it in the most horrific ways imaginable? Why would you do it and film it? Why would you do it and broadcast it to the Israelis?

Hamas went through several stages. First it filmed it, live-streamed it, gloried in it, delighted and danced, and had--Hamas supporters, by the way, overseas, gloried in it and were joyful. The protests in support of Hamas began long before the Israeli bombardment of Gaza began. It wasn't about Palestinian suffering. It was about Palestinian success--at the beginning, certainly at the beginning.

And, the reason is, again, that Hamas understands the basic conflict as raising the cost and eventually the colonialist leaves.

Why hasn't it worked?

Russ Roberts: Because, as Golda Meir said: We have no place to go.

Haviv Rettig Gur: We have no place to go.

This is not a shallow point. And it's not an ideological point. It's not that Zionist ideology tells us we have no place to go. It's not that I tell my children that they're part of this imagined community. All nations are imagined. Is there even such a thing as a nation? It's not any of those kinds of ideational, elitist kinds of conceptions. We have no place to go in both the historical experience sense and in the literal current political sense.

Where do we come from? Fifty percent of us come from the Arab world--50% of the Jews. Most Israelis--most Israeli citizens--are Arabs. If 50% of the Israeli Jews are Arabs and all the Israeli Arabs are Arabs, that's 70% of, 65% of Israelis? I'm not good at math. That's why I went into the Humanities. But, we belong in the Middle East more than in anywhere else.

What does that mean? That means that if you want to kick us out like the French back to France, you have to have a very serious conversation with the Baghdadis. Because about a third of the real estate of Baghdad belongs to Jews who were forced to flee. Are you really sending--yeah?

Russ Roberts: But, not anymore. There's no--just like Palestinian refugees in Gaza, whether they're literal refugees from 1948 or they're descendants, or Palestinians in the West Bank, they can often point to where they lived in Israel. Those places are now owned and lived in by Jews, and most of those Jews are happy there and don't want to give them back.

But, a sticking point in this conflict for decades has been what is called the Law of Return: that Palestinians demand the right to reclaim their lost property, lost birthright heritage. And, I understand that. It's a very powerful and urge that needs to be respected.

But it's a weird thing of course, that the 50-plus percent of Israeli Jews who fled from Arab lands--they're not going back. First of all, they don't want to--

Haviv Rettig Gur: No, but also nobody claims that right for them. In other words--

Russ Roberts: And, no one claims it.

Haviv Rettig Gur: The Palestinians have a unique request: not a return to a State--which quite a few nations have. There's a kind of right of return in Greece. There's a kind of right of return in Ireland. Read the Irish Constitution. There's a special dispensation given for fast-tracking naturalization for people of Irish heritage.

But, nobody has a right of return to a geography in another state. That is a unique demand by the Palestinians. And nobody claims it for the Jews--who are displaced in the same place, in the same conflict, at the same time.

Russ Roberts: Yeah, I called it the Law of Return. That's a different thing. It's the Right of Return.

1:11:38Russ Roberts: In the middle of this very challenging moment for many, many people in 2023, protesters around the world in sympathy with Palestinians or in antipathy to Israel have suggested that the Jews--when they say, for example, 'From the river to the sea'--which means the country we currently call Israel, should be under Islamic sovereignty. And, it's worth pointing out that in the aftermath of October 7th, most Israeli-Arabs--meaning people who are Muslims, not as opposed to say Israelis, who came from Arab countries--most Israeli Arabs here have, I think it's 70% are in support of the Jewish state's actions against Hamas, and are horrified at what happened.

And, one reason is they probably don't want to live under Hamas.

But, 'From the river to the sea,' that includes where they're living in many, many cities in Israel. They don't want to be part of that.

But, when people have been confronted who are chanting 'From the river of the sea,' well, where would the Jews go who currently live between the river and the sea? And, they say, 'Well, they should go back to where they're from.'

And, when asked, they have sometimes said, like, 'Brooklyn.'

Well, most of Israel's 7 million Jews are not from Brooklyn. They're from Baghdad, or Yemen, or Morocco, or Ti'inik[?]. And, they could go back. In theory, I could go back. I have two passports. But I don't want to go back particularly. And most Jews who live here can't go back, because there's nowhere to go back to.

So, what you're highlighting, and this is something I didn't fully appreciate, is that this colonial narrative, this anti-colonial narrative, and this anti-colonial strategy of Palestinian terrorism is wildly at odds with the Jewish narrative.

Now, with Yossi Klein Halevi we talked about the two narratives of 1948, for example. The Jewish narrative is: We'd been here a while; we had a chance to stay, we were attacked. We fought. We won. We gained more territory. In 1967, we were attacked. We won. We gained more territory.

The Palestinian narrative is: in 1948, we're minding our own business. The UN declared a state. We didn't get a say. The world voted. Nations attacked Israel. We were expelled.

Now, some of them were expelled. Some of them chose to leave and then found they couldn't come back or didn't want to come back, and they were put into refugee camps.

So, those are two narratives that don't work very well together.

There's a zero-sum game more or less: only one nation can live from the river to the sea as sovereigns. Right? Now, it's Israel as a Jewish state. The Palestinians, many want it to be a Palestinian or Islamic state. That's a zero-sum game.

And, Yossi Klein Halevi's brilliant, I think, book, and I think impassioned, and I think empathetic book, Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor, makes the point that each side is going to have to give a part of their narrative; and that's worth doing so our children can live in peace and we don't have to die.

But, now there's a second narrative, second set of narratives that don't work. That is: the Hamas and violent part of the Palestinian movement that says, 'Oh, I know how we get this land back. We just make it really uncomfortable for these people to live here.' Not recognizing that that cost-benefit analysis doesn't quite work for us because we don't have anywhere else to go, most of us.

Haviv Rettig Gur: I'll say more than that. It's not just that we have nowhere else to go.

Now go back to everything we talked about at the beginning. Our foundational lesson, the idea at the heart of our identity, what it means to be Israeli more than any other thing that it could possibly mean is that nothing is safe. Nothing is anything but precarious, except being on our own terms, self-reliant in our own land. The founding of Israel is the day we stopped dying, literally. And so, if that is the meaning of Israeliness, and it's a meaning, so foundational--I once heard an anthropologist explain to me that there's a thing in anthropology called a Big Idea. A Big Idea is an assumption so large, so vast, so universally shared, nobody ever talks about it. And so, we don't even notice that we all share this huge assumption until we meet a culture that's exotic and different from us and doesn't share it, and then we don't understand what they're talking about. Right?

The Big Idea: a fish doesn't know it's swimming in water, right? Because it's just breathing. That water that we swim in as Israelis is how is that arc? And, it's an arc that American Jews can't see. Never mind me asking the Muslim world or the Palestinians or liberal Europe to see. It is the Israeli-Jewish experience that in the English-speaking language, in English-speaking discourse--certainly in English-speaking academia--is almost entirely absent from the discourse.

And, it is why the anti-colonial paradigm has done horrific damage to the Palestinians. For two reasons. One, I can't give them what they want. They're exacting a cost from me. And, the idea of this kind of pressure--of all pressure, terrorism, sanctions, social shaming. All pressure, the idea is if you change your behavior, the pressure ends.

But, they're asking for me to change a behavior that is literally who and what I am. It's my one historical lesson from a century of genocide.

And so, the anti-colonial paradigm doesn't work on me. I'm immune to terrorism. Not because I'm brave and courageous and macho and tall and handsome. Obviously we Israelis are all those things, but that's not what made us immune to terrorism. And, because Palestinians don't know that, don't have a theory of mind of us--art, their discourse. Go into their discourse, study it, learn it, empathize with it. You will not find in their discourse an empathetic journey, a self-critical, serious analysis of our story and our experience.

You're going to find a lot of excuses. You're going to find a lot of cheap psychologizing. 'We're the victims of the victims,' the Palestinians sometimes say. In other words, the Israelis were victimized by the Europeans. And, what do you do? Family-systems psychology: you end up traumatizing your own kids the way your parents traumatized you. That's what's happening. That's super-cheap psychologizing. I wouldn't do that to Palestinians. I don't expect them to do it to me.

There is a good reason they cling to the anticolonial paradigm.

And, by the way, everything we've seen on college campuses in the West, everything we've seen from these rallies is this: Decolonization--students at Harvard or Stanford screaming, 'Decolonization. This is what we meant by decolonization.' After the massacre of 1200 Israelis. 'What did you think we meant?' Yeah, exactly. This is 1960s anticolonial theory. They were all forced to read Frantz Fanon, who was this doctor who worked with the FLN and wrote this book called The Wretched of the Earth, which had a profound effect on the global Left.

What's fascinating about this pro-Hamas, cutting edge, American-university ideology is that it's 60 years old. It's incredibly old and boring, and it has already decimated the Palestinian cause, because they're coming at me and demanding something that doesn't make any sense.

And, 'From the river to the sea' is the same story. Rashida Tlaib--Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib--wants us to believe that that means: From the river to the sea, everybody is going to have a vote and we're all going to be a civic democracy like America. And, if you don't think that that's what it means, you're a racist.

The only problem is, in Arabic--including in Western marches--in Arabic, the translation--the text, translated, 'From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,' is, 'From the river to the sea. Palestine will be Arab.' It's a quote from Hamas' charter. And, it is not about establishing a civic democracy. It is about the anticolonial paradigm.

If you're a Palestinian, that anticolonial paradigm still to this day promises you absolute complete redemption. The Jews will leave. Just have faith. And, that's Hamas' popularity. What does Hamas say to Palestinians? It's says to Palestinians: 'We are believers. There is a just God, and the just God oversees a just arc to history.' And so, to make peace with this evil called colonialism that the Jews represent is to not believe in a just God who oversees a just history.

Russ Roberts: So, it's, I think, deeply insightful and deeply disturbing at the same time. Where does that leave us? We haven't talked about it in detail in the program, and I don't know if we will. But, certainly, in the run-up to October 7th, Israeli society was on the verge of civil war, I felt. We had people fighting each other on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year--secular and religious Jews in Tel Aviv. We had pilots refusing to train because they did not like the proposed judicial reforms. We had a minority coalition in charge that pushed a variety of things that the majority of the country did not want. And, we looked like we were falling apart.

And, certainly, many people, many Israelis talked about leaving--going somewhere else. Not necessarily back home, because maybe there wasn't a home they could go back to, but somewhere else. Most of them, I think, were thinking about the United States or Canada.

And, the most horrific atrocities perpetrated on Jews since the Holocaust happens on October 7th.

And, all of a sudden, you and I are living in a extraordinary moment of history--of an amazing unity, an unbelievable pulling together as a country that I've never experienced in my lifetime, having spent the first 66 years, 67 years in the United States.

It's not working, as you say. It's not achieving. The violence is not achieving, at least so far, what the Palestinians had achieved, hoped it would achieve, or what previous liberation movements had achieved.

There is an alternative, by the way, which is the nonviolent strategy that India followed in liberating itself from colonial rule and other places. But it usually takes some kind of violence. America is a perfect example. 1776 was a war that brought about the freedom of the United States.

So, where does that leave us? We are more determined. I like the metaphor--it's a cheap metaphor, but I think it's profound--of the sun and the wind having a debate about who is stronger. And they say, 'Well, let's see who's stronger. There's a man walking down there below us with a coat on.' 'I bet I can get him to take his coat off,' says the wind. And he blows and he blows, and the wind blows, and the man just clutches his coat tighter. The sun comes out from behind a cloud, and the man's hot and he takes his coat off. The sun wins.

Well, Hamas and the Palestinian terrorist movements that exist alongside them and before them, and I fear will come after them, they're the wind. They keep blowing and blowing, and we just clutch our coat tighter, and we say, 'We live here. We're not going anywhere. We'll fight. We'll die for the right to stay here,' partly because we don't have anywhere else to go or don't want to go anywhere else and partly because we believe we belong here. We have a different narrative.

You gave the one about running away. That's our foundational narrative.

But, it's more than that. There's a religious piece to it, of course, that's part of it, that runs alongside that. This is the place we are meant to be as Jews. So, those are really strong, those two together.

But, the Palestinians have not given up. They keep pushing and they exact very painful costs on the Jews who live here, but also on their own people. Hard to be a Palestinian in Gaza. We're seeing the 300 miles of tunnels that exist under Gaza--that Western aid and others have given to Gaza in the name of humanitarian assistance--it's been used to create military infrastructure.

So, you got any cheerful thoughts for me, Haviv? This is--

Haviv Rettig Gur: I hesitate to--

Russ Roberts: We're just going to keep going?

Haviv Rettig Gur: I hesitate to be optimistic in the Middle East, but you want to understand the Israeli-Arab phenomenon you referenced earlier.

Arab-Israeli identification with Israel is at an all-time high. I think the last poll was 72%. It's never been that high. Why? And, that's because of October 7th. In other words, it's spiked, massively: I think more than 10 points since October 7th. What the heck is happening?

Russ Roberts: I just want to remind listeners: Arab-Israelis are people who live within the borders of Israel. They're not on the West Bank. They're not in Gaza. They either didn't flee in 1948, or they found themselves here and their children and grandchildren are still here. They have equal rights with the Jewish population. They have many things that are, I think, very tragic. They don't get very good education. They have, I think, inadequate police protection against violence.

But, they're torn, to some extent, because they do not identify with Zionist project. Understandably. They're not Jews. They're Muslims or other forms of other non-Jewish religions. So, they've been torn. But, right now, they're very much identifying with the State of Israel, at least in the moment. Carry on.

Haviv Rettig Gur: Right. We have tremendous research into the Israeli-Arab identity over the decades. It fascinates academics because these are people who are Palestinian and Israeli and Muslim and Arab living in a majority Jewish state. And so, they are people with a very layered and complex identity who engage deeply with the Israeli body politic. They're in every Israeli university in huge numbers. They work in Israeli industry. They increasingly are seen in the Israeli judiciary and in the Israeli high-tech industry. And, they also have this Palestinian identity.

And, one of the things that we're seeing, of late, certainly in the last month in a profound way--we're seeing it also in civil society: Arab-Israeli civil society has come out in support of the victims' families. Arab-Israeli politicians have been outspoken about Hamas' atrocities. And all of that while they're watching fellow Palestinians in Gaza suffering horrifically.

And, what actually is happening there, I think, is the collapse Hamas has expedited[?]---they speak Hebrew. They know us in a way that Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank don't know us. They don't speak Hebrew. And they know what just happened to us, and they know what just awoke in us. The Hamas Massacre in which people--in which, for the Israelis, the great trauma wasn't the specific murder of a specific child. The great trauma was the feeling of helplessness, because that brings back Kishinev. That brings back old, deep, primordial Jewish thoughts and experiences that created who we are now a hundred years ago.