An Interview With the Vanity Fair Writer Whose Cormac McCarthy Scoop Went Viral for All the Wrong Reasons

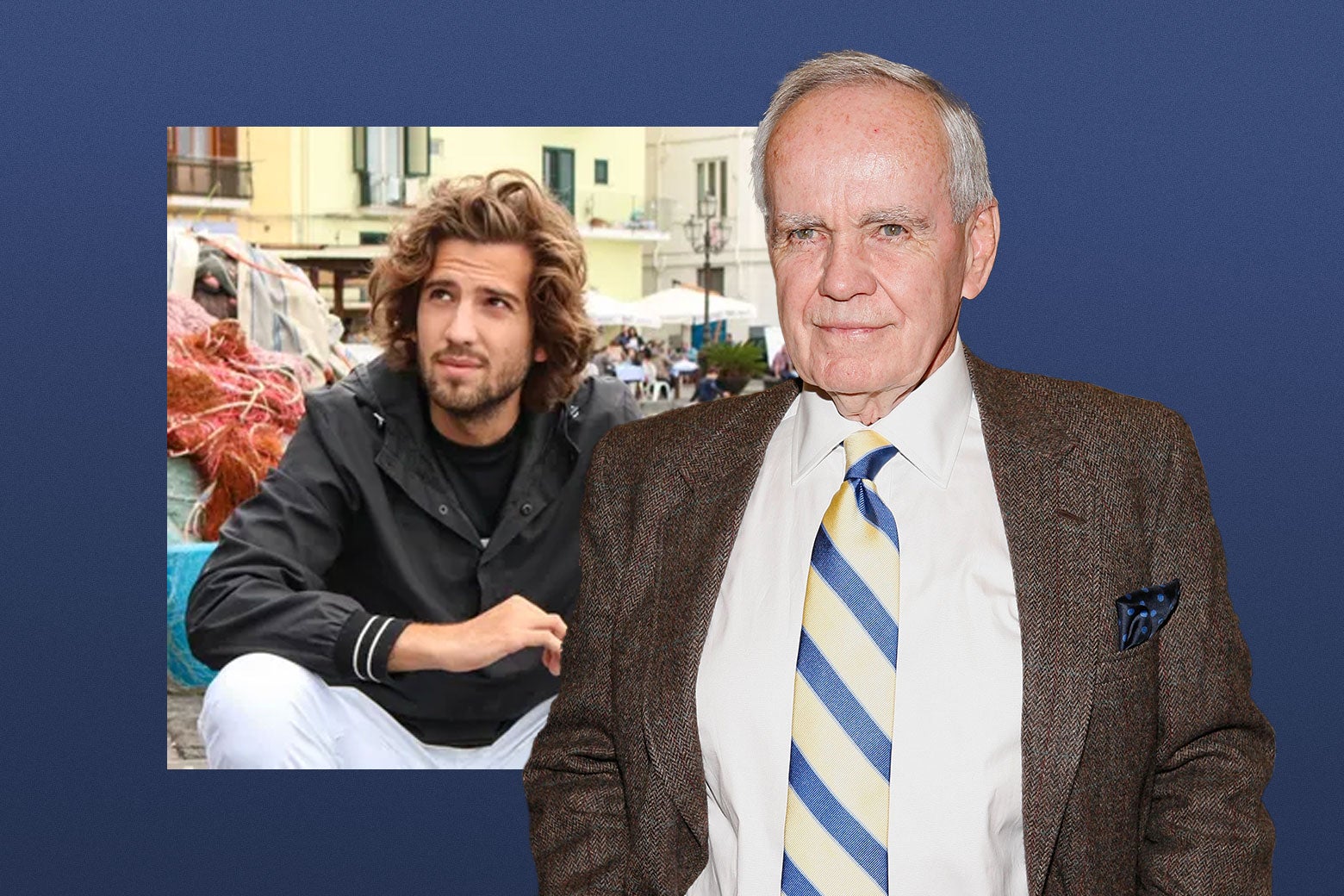

Vincenzo Barney is ready to explain himself.

On Wednesday, Vanity Fair published a blockbuster literary revelation about Cormac McCarthy: The writer had a sexual relationship with a teenager when he was in his early 40s, and for decades afterward, he included versions of her in nearly everything he wrote, including his final two novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris.

Reportedly, multiple biographers have been trying to get Augusta Britt, now 64, to talk to them about her long relationship with McCarthy, which began when she was 16 and turned sexual when she was 17. But she didn’t talk to them. Instead, she talked to Vincenzo Barney, a 2018 Bennington grad and fledgling writer whose reviews of those final novels she’d found on Substack. She left a comment, he followed up, and a year and a half later, Barney published his big break in one of the biggest magazines in the world.

Criticism of the piece has been fierce and has fallen along two lines: The first is that the piece as a whole is irresponsible and that it downplays McCarthy’s abuse of a teenager. Britt insists in the story that she doesn’t feel like a victim, an assertion reflected in the story’s very Vanity Fair headline: “Cormac McCarthy’s Secret Muse Breaks Her Silence After Half a Century: ‘I Loved Him. He Was My Safety.’ ” As Liam Kelly writes in the Telegraph, “Barney seems to treat McCarthy’s pedophilic interest in the vulnerable teenager as a great love story.”

However, that serious criticism has been somewhat drowned out by the gleeful clamor of people quoting their favorite Vincenzo Barney lines. Because, when the greatest literary scoop he was likely to get in his lifetime landed in his lap, Vincenzo Barney did not phone it in. He spent nearly a year living in Arizona, talking to Britt basically every day, and when he filed to Vanity Fair, he did not file a careful, journalistic report. No, he really went for it, delivering the weirdest, most frequently nonsensical, most floridly overwritten story to appear in a legitimate magazine since … maybe since the heights of New Journalism in the 1970s.

Barney went so hard, in fact, that he seems in some ways to have broken the magazine-publishing apparatus. My guess is that Vanity Fair would have had an easier time with a more traditionally written story but that Barney basically forced its hand through the overwhelming sentence-by-sentence purpleness of his prose to just publish it his way. The alternative was to lose the story, and the story was too juicy to lose. What else would you expect from an enormous Cormac McCarthy fan who has had what he believes to be “one of the most profound experiences of my life”—and knows that this is the biggest opportunity of his career?

The problem is, of course, that underneath all the bizarre descriptions of lightning there’s a very difficult story to tell, about a teenager who was taken advantage of, a woman who loved and was disappointed by the man who did it, and a 64-year-old who now fiercely defends her own agency. I sort of grudgingly admire Vincenzo Barney’s willingness to go all out—in a media world where a lot of stories sound the same, that sure wasn’t the problem here. But he wasn’t the writer to grapple with these weighty issues. I don’t know who would be! But it wasn’t a guy so determined to make his mark on the literary firmament that he eclipsed his subject’s story with his own writing style.

On Thursday I emailed Vincenzo Barney, who goes by “Nick,” to ask for an interview. He responded eagerly but looped in Condé Nast PR, who quickly told me that a phone call couldn’t happen because Barney was simply too busy, but that I could email questions instead. I pointed out that writing answers to a bunch of questions would take way longer than just talking to me on the phone, but the publicists refused—presumably so that they could have a look at his answers before sending them to me.

And while they may well have edited some of Barney’s responses, they sure didn’t edit out his personality. In this email Q&A, he addresses the criticism he has received, reveals that he thinks his style is less McCarthyan than influenced by another writer, defends his characterization of Britt and McCarthy’s relationship, and playfully deflects any number of questions, while straight up ignoring one. All that is to say, he responded with the bluff bravado of someone whose dreams have come true, though I think that someday he’ll regret viewing these events in that way. His answers are presented as he wrote them.

Dan Kois: This story seems like it fell from the sky. When did you realize what you had, and how did you feel?

Vincenzo Barney: It did indeed fall from the sky.

In 2023, I had been working for months on a review of The Passenger and Stella Maris for Substack. I posted it on April 1st—and that day my wildest April Fool’s Day wish came true: Augusta discovered me and entrusted me to tell her story to the world. No joke. (We now celebrate April Fools Day as a private holiday.)

Augusta and I got each other immediately and laughed and laughed each night on the phone. (Augusta is one of the funniest humans I’ve ever met.) She was especially amused by the projections of some self-proclaimed Cormac McCarthy scholars (I am not one of those, by the way; I am simply a writer who believes that sometimes the most worshipful scholars and critics understand their subjects the least). This will break a lot of hearts, but according to Augusta, McCarthy had zero interest in Gnosticism, or Foucault.

Augusta had long thought of telling her story—indeed, she says McCarthy actively encouraged her for decades—but it wasn’t until she read my horrible drek on Substack that she felt it could be pulled off: that is, told from her perspective, with my daringly bad style absorbing most of the controversy and opinion columns.

In the piece you say you’ve spent thousands of hours with Augusta Britt. What has that looked like over the past year and a half? Multiple visits to the Southwest?

Tens of thousands of hours may be more accurate. It looked, and felt, and was, idyllic. I lived for 9 months in Tucson. We shot guns, we took care of her horses, we rooted against the Chiefs. We did Zyn and smoked Camel Wide blues and contemplated cacti. I read Moby Dick and drank two bottles of Greek red wine a night, most of which ran down my shirt as Augusta cracked one-liners and prepared us some of McCarthy’s favorite dishes. As is the Southwestern custom, she bought me my first pair of cowboy boots, which I had surgically attached to my feet this summer.

When I was a freelancer in my 20s, I would have killed for a story like this, but how did you afford to report it? You’re working on books, but do you have a day job?

I’m not a nepo baby (though I plan to have several in the future), so I did have a day job. But that didn’t last long out in Arizona. I have an incredible family who have always wanted to see me be called a greasy guido by strangers on the internet, so they took up several financial reins that they couldn’t particularly afford for my benefit. I’m sorry to disappoint everyone, but I’m still penniless.

Augusta is really steadfast that she doesn’t consider herself a victim, that she wasn’t groomed. Do you agree with her? I know that’s a charged question.

I’ve been surprised that so many responses have passed over Augusta’s valuation of herself.

Let us remember, Augusta Britt continued to age and is no longer a teenager but a 65-year-old woman who has had her entire life to reflect on McCarthy, and used her agency several times in their relationship, including leaving McCarthy after finding out he was still married and had a child. Still, it is a charged question. Grown men having relationships with teenage girls is immoral, as is writing sexually explicit letters to them. As I write in the piece, it was also illegal. But I am also deeply uncomfortable contravening a woman’s authority on her own life. Especially as a young man half her age. She has been emphatic that there was no grooming (as recently as again today).

Did you argue about it?

[Barney did not answer this question.]

At what point in the process did Vanity Fair get involved in the story, and how did that happen?

It happened almost immediately. My former professor, Benjamin Anastas, was in the editorial trenches with Radhika Jones back in the ’90s, and he made the connection. The story, I hope it’s obvious now, was not assigned to me, and was not assignable to anyone else.

You talked to McCarthy’s son John. Was that a hard get?

John is a really wonderful and intelligent young man, with a very kind soul. He’s a special cat.

It’s safe to say you’re a McCarthy completist. How has his writing influenced yours?

I used to live by a rule, passed down by my father: “Don’t read living authors.” One day that changed. I came down the stairs one Saturday morning at the age of 15, pausing halfway down, my hand slowing on the banister, to find my father silent in his recliner. “Son,” he said to me. I knew what he was about to say would be important. “There is one living writer you can read.”

Reading Blood Meridian at the age of 15 was like getting high. McCarthy was my introduction to the inventive malleability of the word. Without McCarthy, I would never have developed my bold, nonsensical style.

Just for the record, I also write fiction and have a novel set at Bennington that everyone is going to hate. I can’t wait to share it with the world!

Did reading those letters change how you felt about McCarthy?

As a person? Yes.

Have they changed my feelings about him as a writer? No.

When you sat down to write, did you consciously want McCarthy’s style to inflect the piece?

I hate to say this, but I felt I wrote the piece with my own style. Is such a thing possible? My general approach was mostly painterly, impressionistic. (I can hear the groans and patter of furious little thumbs on X as I say this.) However, there was no way to write the southwest or Augusta or McCarthy himself without dropping into his register. But the style I was most trying to steal from was, and I hope this pisses a lot of people off, Martin Amis.

Martin Amis! Can you tell me what aspect of his style influenced you the most while writing this piece?

Just about everything. Very few have written better sentences than Amis. He stands on the opposite end of the spectrum from McCarthy. Both play God in their novels, McCarthy from the third person with his complete cosmogonies, and Amis from the first person, with the private cosmologies of his megalomaniacs. And he passed eerily close to McCarthy, which means my father allows me to read him now. In the unsung Zone of Interest, Amis records the greatest phraselet in the English language, “glueyly asquirm.” I will forever be trying to top that, or find a way to steal it. In fact, I’d like very much for my critics to start saying I’m an Amis wannabe, not a McCarthy imposter.

Did you think about writing it in a more traditional journalistic style?

Not once. My original draft had no quotation marks.

What was your editorial process like? Did you wrestle over style questions at all? Or was Daniel Kile, who edited the piece, receptive to your choices?

Wrestle? At dawn Daniel and I would square off on a mat and grapple over commas, question marks. I was most receptive to Daniel’s rear-naked choke. In fact, he’s editing this interview as we speak. The bell is about to go off for the next round. I haven’t much time.

I can see from your Twitter that you’re definitely aware of how people are responding. Readers are really coming at you for purple prose. Is that annoying?

More people have been coming at my purple shirt, unbuttoned to the chest in my profile photo. And my hair. And my name. You can blame the artistic genius who created me (my mother), for the name and the hair. My favorite thing I’ve read is that I look like my style, and that I write as if my hair is holding the pen.

As for my style and the profile itself, Augusta loves it, and she has great taste. McCarthy also liked my writing. I’ve received just as many complimentary and thoughtful responses from readers. Most of them have taken place, if you can believe it, not in the cesspool of X. I do want to apologize, though, for having a personality and writing the way I like to. I’ve talked to doctors about it and there’s really not much I can do. My next piece is going to be so purple, so hyacinth, so ultraviolet—whoops, there I go again.

To me the piece reads like you have had a very profound experience meeting Augusta, and that you’re doing everything you can to convey that on the page. Does this sound right to you?

I appreciate that reading. It has been one of the most profound experiences of my life.

I’ve profiled people who had a huge impact on me. You fall for them a little bit. That’s part of the point! Did you fall for Augusta?

Everyone falls for Augusta.

There are other biographers chasing this story. How does it feel to be the one who got it?

Fate. I will never be able to repay Augusta for trusting me with her life story. Anything else I do going forward, I owe to her.

Get the best of culture

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.