Written by Lipton Matthews.

The portrayal of slaveowners as inherently sadistic figures is common. Both popular and academic sources frequently rehash the tales of Thomas Thistlewood and Arthur Hodge – two men that are infamous for their cruel treatment of slaves. Thomas Thistlewood pioneered “Derby’s dose”, which involved the forced consumption of human feces for offenses such as stealing and absconding. The lesser-known Arthur Hodge made headlines not only for brutalising slaves but also for murdering them. (Hodge was eventually found guilty and hanged.) Due to their unusually callous personalities, Thistlewood and Hodge have become the stereotypical representations of slave masters.

Yet historical evidence suggests that the brutality of slavery was shaped by production systems and crop requirements, rather than solely by individual malice. In this article I examine how socio-economic factors influenced slave conditions in a range of societies, from Ancient Greece and East Africa to the sugar plantations of the British Caribbean. I conclude that while some forms of slavery were indeed marked by extreme violence, others were far less brutal, owing to the demands of specific agrarian economies.

In Ancient Greece, the brutality of slavery was clearly influenced by economic incentives – as George Tridimas demonstrated in his analysis of Athenian chattel slavery and Spartan helot servitude. Athenian slaves were used in a wide range of tasks, from agriculture and household labor to skilled trades. Skilled slaves, especially those involved in specialized crafts, were seen as valuable assets and were sometimes even allowed to earn wages or buy their freedom. Moreover, they were treated with comparative moderation, as Athenian slaveowners sought to protect their lucrative investments.

By contrast, the Spartan system relied on the total subjugation of helots – agrarian slaves who were essential to sustaining Sparta’s martial society. Helots worked the land to provide food for the Spartan citizens, who were engaged in military training. Due to their large numbers and the Spartans’ constant fear of rebellion, they were treated with immense brutality, including periodic state-sponsored purges aimed at limiting their population. Unlike the Athenians, Spartans relied on brute force to keep the helots in line.

Robert C. Allen’s study of slavery in East Africa during the 19th century provides insight into how specific crop types influenced the harshness of slave treatment. In regions where labor-intensive cash crops like cloves were produced, slaveholders subjected slaves to grueling conditions in order to maximize their productivity. Slaves in Zanzibar, for example, endured backbreaking labor under poor conditions, driven by the high profitability of the labor-intensive clove production.

Conversely, regions focused on the cultivation of less labor-intensive crops, such as dates or grains, required a more stable workforce, resulting in comparatively milder treatment. The economic rationale was straightforward: while the profitability of clove plantations was highly dependent on the input of labor, this was not the case for subsistence and low-yield crops. Allen’s work shows how crop type affected labor intensity, which in turn affected the degree of brutality slaves experienced. It suggests that profit-driven motives lay behind the differences in treatment of slaves in different regions.

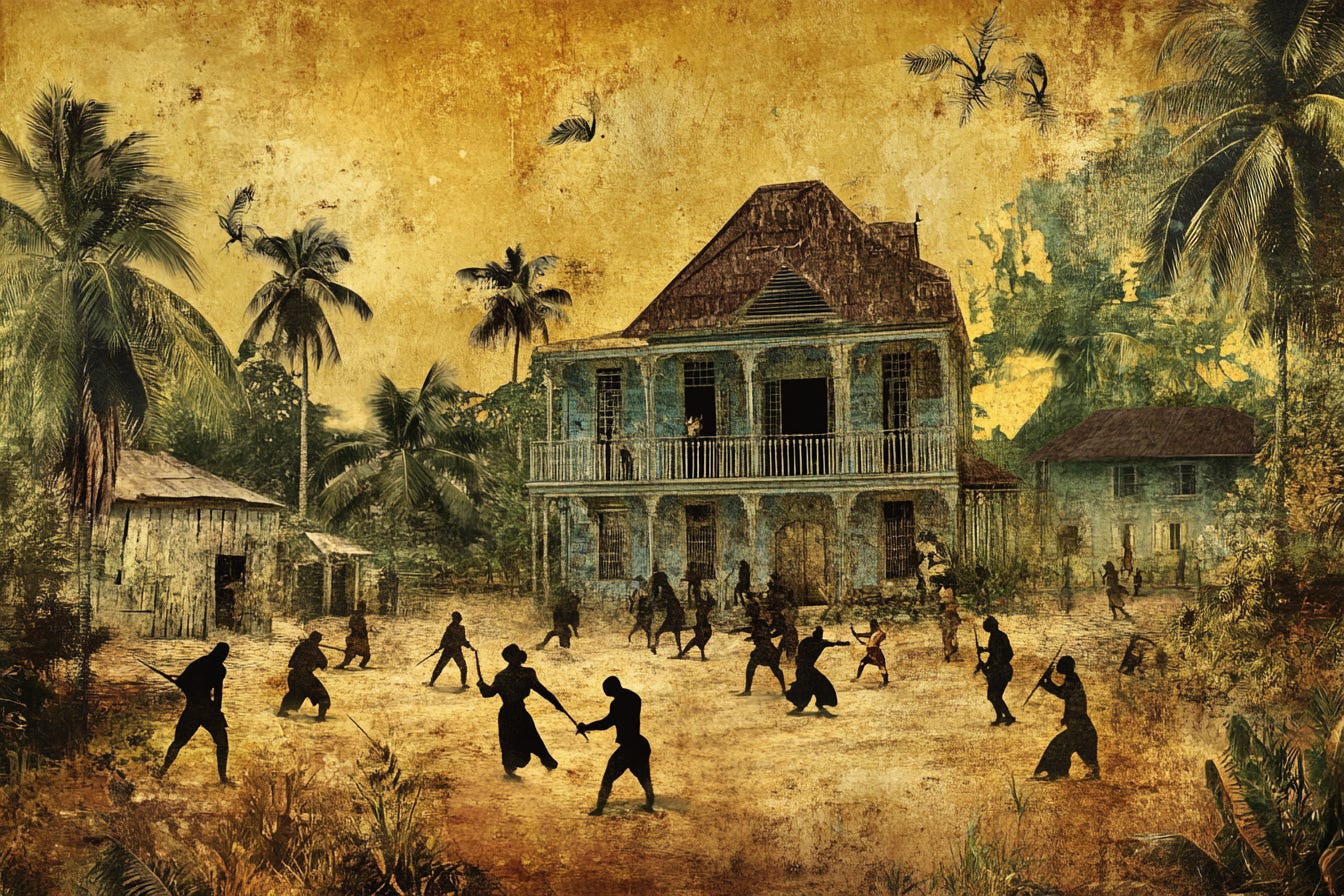

In the Caribbean, sugar plantations stand out as an example of particularly harsh slave conditions. Why? Michael Craton has argued that brutality in sugar economies resulted from the high demand for labor and the immense profitability of sugar. Plantation owners viewed slaves as replaceable parts of the production process, leading to a brutal cycle of overwork and high mortality rates. Rather than investing in the long-term productivity of their slaves, sugar plantation owners found it economically advantageous to work them to exhaustion and then replace them with new laborers from the Atlantic slave trade.

Similarly, Michael J. Jarvis’s study of maritime slavery in Bermuda shows how the demand for labor in specific economic contexts led to less severe treatment of slaves. In Bermuda, maritime slaves performed skilled work essential for the operation of ships and, therefore, of the island’s broader economy. As a result, these slaves were often afforded relative autonomy. They enjoyed a level of trust that was largely unknown on Caribbean plantations. As in the case of ancient Athens, the skill demands of maritime labor moderated the degree of brutality to which slaves were subjected.

These skill demands also had a lasting legacy. The premium Bermuda’s slaveowners placed on skilled labor meant that slaves acquired various technical competencies, which they were able to use to their economic advantage after emancipation. The demand for skilled labor helped foster a culture of productivity and adaptability, which laid the foundations for the island’s relative success in modern times.

Barbados provides an additional example of how socio-economic factors during the era of slavery influenced post-slavery outcomes. As Robert Proctor and Olwyn M. Blouet’s studies demonstrate, Barbados implemented educational programs for slaves in the early 19th century, a policy that was practically unheard of in other slave societies. These early educational programs were driven partly by British colonial authorities’ efforts to stabilize the island and prepare it for eventual emancipation. The aim was to cultivate a more literate and disciplined labor force, thereby mitigating social tensions and ensuring slaves could work productively in a non-slave economy.

As a result, Barbados entered the post-emancipation period with a relatively high rate of literacy, setting the stage for further educational advancements. Blouet’s work reveals that, although limited, the programs had lasting impacts on the socio-economic landscape of Barbados, contributing to its high levels of education and relative economic stability today.

What’s more, these enduring impacts are evident in contemporary studies of cognitive and economic outcomes across former slave societies. Bermuda and Barbados, both of which developed distinct socio-economic structures favoring skilled labor and early education under slavery, exhibit higher average IQ scores than countries like Jamaica, where the slave economy prioritized labor-intensive crops over education or skill development. The correlation between historical labor demands and present-day cognitive outcomes underlines how the socio-economic foundations of slave societies continue to shape those societies in subtle but significant ways.

Many historical accounts portray slaveowners as inherently sadistic figures. Yet the brutality of slavery was profoundly influenced by the economic imperatives of the societies in which it occurred. From the skilled labor demands of ancient Athens to the extreme exploitation on Caribbean sugar plantations, economic factors shaped the degree of brutality slaves experienced, as well as the legacy of the systems themselves. Bermuda and Barbados provide notable examples where skilled labor requirements and early education policies contributed to the development of socio-economic advantages that endure today.

Lipton Matthews is a research professional and YouTuber. His work has been featured by the Mises Institute, The Epoch Times, Chronicles, Intellectual Takeout, American Thinker and other publications. His email address is: lo_matthews@yahoo.com

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Subscribe to Aporia

Social science. Philosophy. Culture.