Speedway1/Getty Images

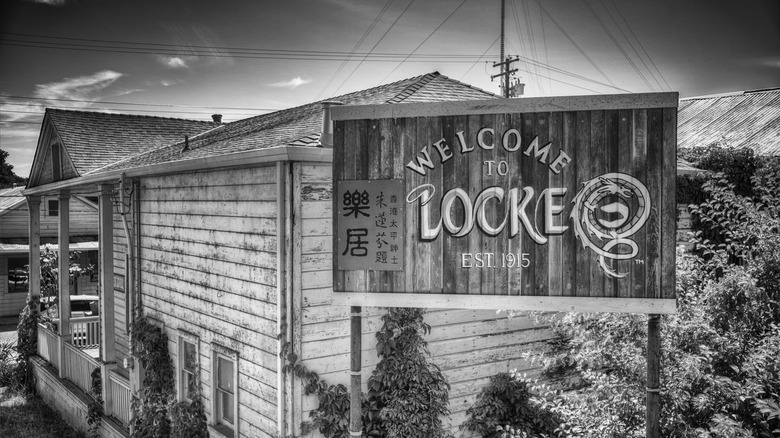

Asian-American history in California is not without a certain level of turmoil and hardship. But like many seeking the "American Dream" yet nostalgic for their cultural past, a group of early 20th-century Chinese laborers built a haven that spoke to their ancestral land but was inextricably linked to California's industrial history. Founded in 1915 by Chinese immigrants from the Guangdong Province working in the agricultural industry, Locke, California, is a hidden community nestled among farmlands. The community was borne out of loss, a rebuilding of a Chinese diasporic population following the tragedy of a fire in the Chinese community in nearby Walnut Grove. While Locke began humbly on leased land with just three buildings — including a store, hotel, and restaurant — today, it is the best preserved and most extensive example of a historic Chinese farming town.

Located just 30 miles south of the state's modern capital of Sacramento, Locke grew in size and cultural impact during an era of America's history when Asian-American exclusion was at its height. But, with continued anti-Asian legislation throughout the 20th century and the economic depression, Locke was threatened with extinction, a fate that many of its fellow rural Chinese communities faced. However, in 1990 the town was designated a National Historic Landmark in a move that preserved this important slice of Chinese-American history. As other venues of Asian-American history are threatened by modern challenges — in fact, one of America's top endangered historical sites is Philadelphia's Chinatown — Locke is a vital exhibition of Chinese history in California.

What to see in Locke's Historic District

Speedway1/Getty Images

Locke's historic Main Street is a narrow roadway flanked by the antique yet character-filled buildings crafted by the town's founders and descendants. With architecture reminiscent of the bright, colorful homes of Caribbean towns, Locke's Chinese language school, saloons, men's clubs, and boarding houses are among the preserved buildings that travelers can now visit. Other buildings which may have started out as one of the aforementioned establishments are now open and operated as shops and restaurants for visitors. The Chinese Cultural Shop, for instance, is a local Locke gift shop which stocks a number of educational and cultural materials on Chinese heritage, as well as local town souvenirs. Meanwhile, Locke Garden Restaurant is located in a building original to the town's founding; it began life as a beer parlor and is now a Cantonese restaurant with an owner that remembers much of Locke's pre-preservation past. In fact, many descendants of Locke's original inhabitants still call the area home today, a unique extension of the town's legacy into contemporary California.

Another can't-miss site in Locke includes the Dai Loy Museum, a preserved gambling house and men's association that tells the story of how the Dai Loy was a de facto center for diasporic Chinese-Americans seeking community. Not unlike how many churches served as centers for European-founded settlements or how fraternal organizations fund community projects, Dai Loy was a civically focused, grassroots group of people that bonded over the improvement of their town. Participation transcended racial boundaries; those of Japanese, Anglo, and Filipino descent also frequented the Dai Loy and participated in informal meetings. The Dai Loy, along with the other preserved buildings of the past, all tell the story of this vibrant rural community's history.

Discover the history of Locke

Toddarbini/Getty Images

While it is more commonly known that Chinese immigrants and Asian-America diaspora worked on the Transcontinental Railroad in California, the history of migrant Chinese laborers in the state's agricultural history is discussed less frequently. Upon the railroad's completion in 1869, Chinese workers, particularly from the Guangdong Province who had experience farming in the Pearl River Delta in China, were employed to construct levees in California's Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. The levees made room for larger farm operations, and the expansion of agriculture and a population of skilled Chinese laborers meant a booming farming hub. In this era of simultaneous agricultural growth by the hands of Chinese workers and Asian exclusion, Locke was borne as "an autonomous island of Chinese culture," as described by the Locke Foundation, today's town stewards.

Locke quickly became a hub among rural farm workers not unlike the overlooked town of Waipahu in Hawaii or the underrated Stedman-Thomas Historic District in Ketchikan, Alaska. With a population of 600 residents, several markets and restaurants, a post office, shipping wharves, and canneries (the town even had its very own speakeasy during Prohibition), Locke was a bustling epicenter of culture and commerce. But like many rural, agricultural towns in the American story, Locke's economy fell in the shadow of the Great Depression. Residents left for urban centers, and storefronts fell into disrepair. However, with its 1990 designation as a National Historic Landmark, preservation efforts from the Locke Foundation, as well as the residents, have both revitalized Locke and restored it to the era of its ancestors, so that visitors today can learn of Chinese-American culture and its contributions to the crafting of California.