Yesterday, Tomorrow, and Banished Forever

The Andersons were kicked out of Disneyland’s most exclusive club. They would not go willingly.

By , a National Magazine Award–nominated journalist and the creator of several podcasts

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Courtesy of the Andersons, Adrián Monroy/Medios y Media/Getty Images

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Courtesy of the Andersons, Adrián Monroy/Medios y Media/Getty Images

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

September 3, 2017, was like so many other late-summer evenings at Disneyland. As the heat began to break on Main Street, swarms of exhausted families packed up their impulse purchases and their double-wide strollers and called it a day. It was almost 10 p.m. when security received an urgent dispatch. A guest was apparently showing signs of distress on a log-cabin-style bench outside Grizzly River Run. Officer Robert Rodriguez arrived on the scene dressed in his uniform with rainbow Mickeys on the short sleeves and a gold-trimmed peaked cap. Rodriguez asked for the man’s license; instead, he pulled out his card for Club 33, the park’s secretive, invitation-only private club.

Rodriguez did not realize yet that the barely cogent man was Scott Anderson, Club 33’s most notoriously outspoken member. But he knew he needed to get him out of the park — conspicuous drunkenness at Disneyland is strictly forbidden. He asked Anderson to call a friend to come collect him. “Come get me,” Anderson snarled into his home screen. Growing increasingly frustrated, Rodriguez took Anderson’s phone and returned a missed call from what turned out to be another Club 33 member, Adam Torel. Torel was nearby at the Grand Californian Hotel. He rushed back to find his friend surrounded by security guards. “Guest Adam showed up and said he would help Guest Scott,” Rodriguez would later write in his official report on the situation. Torel pushed Anderson slowly out of the park in a wheelchair, past stragglers leaving the World of Color light show and bachelorette parties staggering down the imitation cobblestone in their matching T-shirts and sashes.

Club 33. Photo: Lydia Horne.

Club 33. Photo: Lydia Horne.

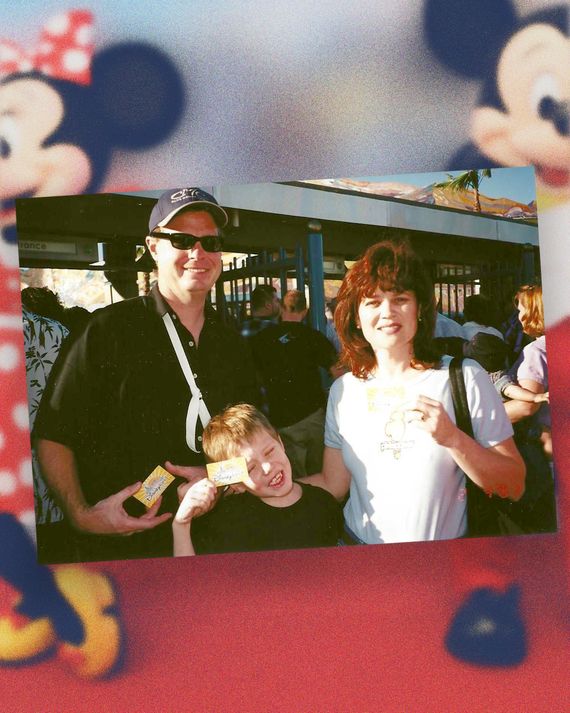

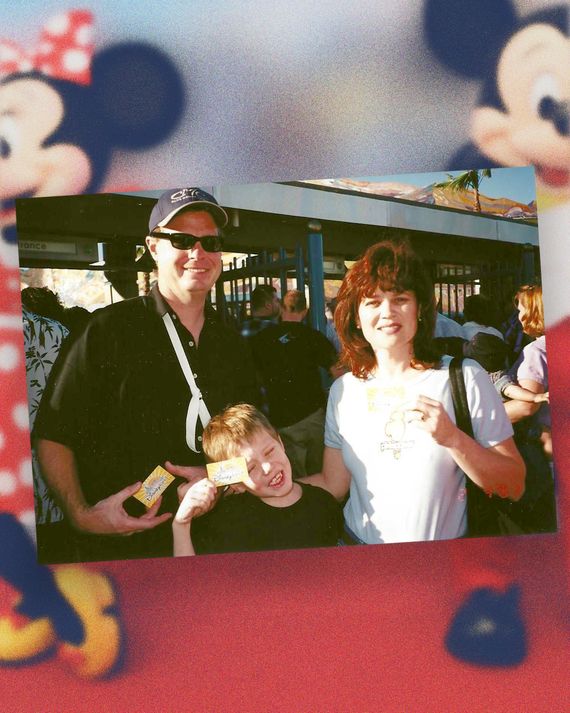

It wasn’t until Diana and Scott Anderson went to Disneyland with their child that they really understood it. The couple had been together since they were 16 years old, through college at Arizona State and afterward, when he took over his family’s electronics-manufacturing business in Mesa, a sprawling town outside Phoenix. Their earlier trips to the park were nice but not particularly memorable, Diana says — they went on a few rides, ate the churros, enjoyed the flag retreat. But with Stuart — “Stumanu” to his parents —the place transformed. Pushing him in his stroller down Main Street, under the blooming olive trees, the new parents felt calm. The air smelled of burnt sugar and popcorn butter, a train whistled in the distance, and their son was quiet. (Disneyland pipes scents onto its streets through so-called Smellitizers in the hopes of evoking this exact feeling.) As Stuart grew, they, like many millions of Americans, made Disneyland their special family tradition. “That’s how it gets you,” Diana says. “Stuart lost his first tooth at Disneyland. He went to the bathroom by himself for the first time at Disneyland. He fell asleep in the stroller for the first time in his life at Disneyland.” By the time Stuart was a toddler, the couple were traveling to Anaheim so often they figured it made sense to buy annual passes. For only $200 a year — it’s since multiplied —the family would be able to visit the park 365 days a year and get comped parking. Plus they’d receive a subscription to Disney News magazine. Best of all, they began receiving the occasional invitation to member-only events. In 2001, they were invited to a preview of California Adventure, a new park-within-the-park — 72 sprawling acres of Pixar-and-Marvel-themed rides and characters. Scott broke his shoulder earlier that day, but the family decided to make the trip anyway. “We weren’t missing the grand opening,” he says. By the time Stuart was 12, he’d been to Disneyland 115 times. He had experienced the 199-foot vertical drop on the Tower of Terror, ridden on California Screamin’, a roller coaster that soared over a giant lit-up Mickey head, and celebrated the park’s 50th anniversary, the so-called Happiest Homecoming on Earth.

Inside Club 33. Photo: Lydia Horne

Walt Disney decided to build his own private club after visiting the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. The idea was to create his version of the suites he saw there, where Disney investors could entertain clients and bring their families. Like everything else at the park, it was designed with his obsessive attention to detail, with help from Mary Poppins’s set decorator Emile Kuri. Disney imported a reproduction of a Victorian-era French elevator to carry guests between floors. An animatronic vulture perched in the dining room was designed to chat with guests while they ate. (Microphones were hidden in lamp fixtures; an actor was hired to sit in a sound room, listen in, and chatter back.) The walls were hung with hand-painted animation sheets from the original Fantasia; a drawing room held Lillian Disney’s exotic butterfly collection. The dining room overlooked New Orleans Square, a replica of 19th-century New Orleans, so guests could look out over the throngs of visitors below while they ate. And the entire place was hidden behind a door painted in “Go-Away Green” — a proprietary-to-Disney color that is supposed to make it more difficult to spot.

Scott and Diana Anderson. Photo: Courtesy of the Andersons

By June 2012, Diana had given up hope on ever getting in. Stuart, already a young adult, had lost interest in anything related to the park. But then, out of nowhere, there it was: a small envelope sealed with a gothic “Club 33.” Her hands shook on the drive home from her P.O. box. She knew enough to know what this meant. Disney with no hassle, forever. Proximity to celebrities. Status. She couldn’t wait to tell Scott. “I said, ‘We got the invitation.’ And he’s like, ‘No way.’” The initiation fee was $40,000, plus another $12,000 annually. “I didn’t want to tell Scott the price because it wasn’t what he was expecting,” she says. But she hurried through the application anyway, afraid all the spots would be taken before she was able to finish. “Diana’s long-term intent was that when we get old, Stuart likes it,” Scott says. “We hoped the membership would live on forever.”

In the summer of 2014, the Andersons went out for dinner with their friends at the club, Ted Crowley and his wife, Jennifer. Both couples had been members for about three years, and both lived in the Phoenix area. Ted worked in the same office as the Andersons’ financial broker. But one night, during a late dinner, Diana says, things took a turn and Crowley touched her inappropriately. After that, Scott made it his mission to get Ted kicked out of the club. In the meantime, he and Diana refused to visit if they knew the Crowleys would be around. On June 2, 2015, Scott emailed the club’s manager, James Willoughby, a subtle reminder: “Love the direction the club is heading,” he wrote. “Only negative here is [with] a few non-compliant members. Usual suspects I’m afraid.” Later, he RSVP’d to a wine dinner only after learning that Crowley would not be attending, “as he was the only reason that I did not put in in the first place.” Scott wrote again to Willoughby to say he overheard an employee, just back from maternity leave, complain that Crowley said he “loved hugging you and it’s not because of your big breasts.” Three days later, he followed up once more: “I am sure that Disney does not take sexual harassment lightly, so trying to understand the process here,” he wrote, signing the letter “Left Wondering.” (Ted Crowley didn’t respond to request for comment.)

If the club maintained its essence after the renovation, Stedman ushered in changes. According to Club 33 administrator Bonnye Lear, who died in 2024 after being thrown from a golf cart racing through Critter Country, the warning policy had been vague under former managers. One current member told me that drinking, which had always been tolerated, if not encouraged, came under enhanced scrutiny when Stedman took over. “We’re normal people. We don’t drink a lot,” this member told me. “I have one or two cocktails,” but with Stedman in charge, “I’d be like, Am I going to get in trouble for something?” The Andersons, meanwhile, were convinced Stedman hated them. They began to believe that the managers viewed members as mere visitors; that they were wielding their power recklessly over those they perceived as enemies of the club.

On the Sunday before Labor Day 2017, the Andersons had been avoiding Club 33 on purpose. They felt like the waiters were watching them. So instead, they spent the day at 1901. (Club 33 members are automatically given 1901 membership.) During a Fantasy Football draft with friends, they ordered two bottles of Sangiovese, several beers, beef tacos, and two pulled pork sandwiches. At 9:31 p.m., the tab was reopened to accommodate one more bottle of medium-bodied red. Then, all of a sudden, Scott says, he didn’t feel well. He recognized the symptoms immediately. A vestibular migraine coming on — and fast. The first one had taken hold 30 years earlier, on the drive to his old Pinetop-Lakeside cabin. The condition was triggered by a lot of things: altitude, junk food, rides that send you in loops, barometric-pressure changes, the taurine in Red Bull, and red wine. “I started popping my ears and belching. It’s just what occurs before I get going into migraine mode. I was like, ‘I got to get out of here,’ told Diana my head was bothering me, and I was going to go back to the hotel. I excused myself and I left.”

Since being exiled from Club 33, many of the members with whom the Andersons were close no longer answer their calls. Instead, they’re spending more time at another Los Angeles members-only club, the Magic Castle. That club — meant for magic enthusiasts — is bigger than Club 33. It has five bars, a library, and a couple thousand members. It’s not that hard to get in. A performer at a 9-year-old’s birthday I recently attended offered me free guest passes in exchange for a five-star Yelp review. Still, there are some touches that a Club 33 member might appreciate — in the music room, a piano is played by an invisible “Irma,” the Castle’s resident “ghost,” who takes musical requests. There are Houdini seances. There are cocktails.