Part I

“Like insurance, lifesaving devices are hard to value. If you don’t need them, they’re useless, even a bother. If you do need them, they’re priceless.”—POPULAR MECHANICS, 1962

DECEMBER IN CHICAGO and there’s some loon pretending to drown in the Sheraton Towers Hotel pool. It’s an indoor pool, but still. This guy is floating in there in a white T-shirt and jeans, upright, with his head lolled back and his eyes closed, sneakers just grazing the bottom. An inflatable plaid life vest barely holds his face out of the water. Later, he grabs for a floating cushion, but that slips out of his hands and he sinks up to his forehead reaching for it.

“We’ll make a life raft and some life preservers. I read how to do it in Popular Mechanics."

This man’s name is Bayard Richard, and you shouldn’t worry about him. He swam backstroke for the University of Wisconsin and can make it to the edge of the pool and climb out whenever he wants. Richard is thirty years old and works at Popular Mechanics in the promotions department. Mostly he comes up with ideas to get companies interested in buying ads—mailers, meetings, stuff like that. It’s a great job: He makes about $5,000 a year, and the office, on East Ontario Street, has a coffee cart and two secretaries. Besides, if you offer yourself up to help the editors execute some scheme like testing life jackets in a hotel swimming pool, you get paid a dollar. Richard climbs out of the pool to try another device. He’s testing them one at a time—a vest, a second vest, a belt, a floating jacket, that useless cushion. Each time, the outdoors editor pushes Richard into the pool and watches to see how he comes up. Richard plays it up for the camera, closing his eyes, holding his breath for a second or two, flopping back, playing dead.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Frank Morris requested five magazines before his escape. The FBI didn’t seem to think Chess Review was relevant.

The shoot takes about two hours, and then Richard changes into dry clothes and a warm jacket and gets his dollar from petty cash. He takes the train home to the house he just bought in Park Forest, and that’s the end of it. He doesn’t see the article, “Your Life Preserver—How will it behave if you need it?” when it comes out in March 1962. He doesn’t even realize the editors used (and misspelled) his name. In fact, Richard doesn’t think about the article again for forty-five years, until his grown son Paul is drinking a cup of coffee and turns on a documentary on the History Channel about the 1962 escape from Alcatraz. The host talks about the frigid waters of San Francisco Bay, a major deterrent to potential jailbreakers—and how the infamous 1962 escapees found a solution in an edition of Popular Mechanics in the prison library. The host holds a copy up to the camera. There in the grainy photos, recognizable from the crew cut everyone in the family jokes about and the nose Paul and his brother David share, is a thirty-year-old Bayard Richard. Paul nearly chokes on his coffee. As David remembers it, “Paul’s looking at the television going, wait a minute, that’s my dad!”

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Part II

“I just thought to myself, that’s one of the most incredible stories I’ve ever heard.”—RICHARD TUGGLE, screenwriter, Escape From Alcatraz

ONCE THE CHICAGO-BASED editorial department completed the life jacket article, the story went with the rest of the March 1962 issue to a printing production facility in midtown Manhattan. Just one copy made it from there to Alcatraz’s dedicated post office at 7th and Mission Street in San Francisco (no zip code, as these did not exist until July 1, 1963). A mail vehicle brought the magazine to the Pacific Street Wharf, where it boarded a steamship that ran to Alcatraz twice a day, every day except Sunday.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Inside the prison, the issue would have gone straight to an administration office, where censors would remove any content that might help convicts escape. But the story on life jackets, with the photos of Richard, survived, and the magazine reached the library intact. There it was added to a delivery cart that a prisoner pushed from cell to cell.

Like all Alcatraz residents, Frank Morris had about four hours of free time after dinner until lights out. That’s likely when he saw the issue for the first time, sitting in his dank cell about the size of a pool table. He may have lain on his bed and put his feet up on the toilet, listening to the seagulls and the sounds of life floating across San Francisco Bay from the city, and imagined how he himself would float over the bay like a seagull, to drink in bars and meet a girl and procure a car to drive to Mexico. And then, looking at Bayard Richard there in that pool in Chicago, Frank Morris had an idea. The story of the escape is legend, thanks in part to the 1979 movie Escape From Alcatraz starring Clint Eastwood as Morris. What happened: Morris (imprisoned for bank robbery), along with brothers John and Clarence Anglin (also bank robbers) and Allen West, a fourth coconspirator who ended up staying behind, chipped out the disintegrating concrete around the air vents at the back of their cells, expanding the holes until they were large enough to accommodate a person. They crawled through the holes into a utility corridor, and then established a secret workshop above their own cellblock, hanging blankets to hide themselves from patrolling guards. Over time, using more than eighty tools they created or stole, the four men made dummy papier-mâché heads to fool the guards into thinking they were still in their beds. Then, on June 11, 1962, Morris and the Anglins climbed a broken utility shaft, ran across the roof, and left. They were never seen again.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Even people who have studied the escape for years will never know whether Popular Mechanics gave Morris the idea to attempt it, or simply provided a method. The magazine certainly contributed to the likelihood of success. Even the FBI and the Federal Bureau of Prisons seemed to think so. Screenwriter Richard Tuggle noticed references to this publication in both agencies’ files while researching the screenplay that would become the Eastwood movie. “I think it’s safe to say that if those guys had not had Popular Mechanics, they never would have tried to escape,” he says. “The magazine gave them the final key that they needed to be able to try this crazy thing.”

In the movie, Tuggle included just one line to explain how Popular Mechanics might have inspired the convicts. In the lunchroom with the Anglins, Morris (Eastwood) whispers his plan to tunnel through the concrete at the back of his cell and then build something to carry them through the frigid, roiling bay to the mainland.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

“You’re gonna steal some raincoats, some contact cement,” Eastwood-as-Morris says. “We’ll make a life raft and some life preservers out of it. I read how to do it in Popular Mechanics.”

Ten days after the convicts disappeared, the Coast Guard found a homemade life vest off Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, but no bodies.

Part III

“When you have all the time in the world, like these fellas did, it’s amazing what a person can do.”—DON EBERLE, FBI agent in charge of 1962 Alcatraz escape investigation

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

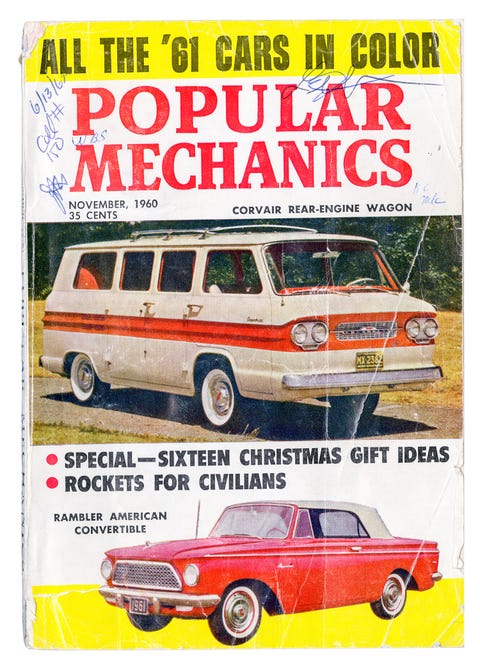

THERE ARE ACTUALLY two issues of Popular Mechanics in the Alcatraz file at the Park Archives and Records Center in San Francisco’s Presidio National Park, and both are in remarkable condition considering how many prisoners, law enforcement officers, and historians have pawed through them over the years. The corners are ruffled and the paper has gone soft, as if it’s been conditioned by sea breeze. But the covers are still bright—headlines promising a “Go-Anywhere Boat,” “All the ’61 Cars in Color,” and a “Power Tower for Toting Tools” over photos of Chevys and speedboats in washed-out turquoise and red and yellow. If they weren’t marred by the signatures of FBI agents, you could frame the covers and hang them on a wall.

The other issue is from November 1960. In it is an article about a hunter who builds his own goose decoys out of found rubber using a technique called vulcanizing. To people who think about vulcanizing at all—which is to say, almost nobody—this is a fairly boring process by which sulfur or other curatives create water-resistant links between rubber molecules. To Morris and the Anglins, though, it was information worth its weight in government pardons.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

“Step one—cut the pattern from an old rubber inner tube.”

It was a common belief at Alcatraz that if anybody beat the prison’s escape-proof reputation, the government would close the facility. So when Morris and the Anglins came asking for raincoats, lots of convicts obliged, happy to play even a small part in shutting down the Rock. They wore their own rubber coats out to the yard and then dropped them so the would-be escapees could casually pick them up and carry them back to the secret workshop. Morris, the Anglins, and West amassed at least fifty raincoats this way.

“Step two—seam edges are buffed and spread with solvent, then vulcanized with thin raw rubber strips.”

Over several months, the four prisoners secreted rubber cement (many varieties of which include vulcanizing agents) from Alcatraz’s cobbling and glovemaking shops, and then spread it on the seams of the raincoats to join them into a raft.

“Vulcanizing takes about 15 minutes, and welds the nine cut-out sections into an airtight shape.”

By March 1962 the raft was nearing completion, but the prisoners weren’t ready to leave just yet. A new issue of Popular Mechanics had just arrived. And wouldn’t you know it, there was a life vest demonstration inside.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Part IV

"Alcatraz sells."—John Cantwell, Alcatraz ranger

THERE IS ONE PERSON who has spent more time inside Alcatraz than any criminal: National Park Service Ranger John Cantwell. On a blustery day in 2021, near the end of 30-plus years on the island, he opens the gates to the Anglin brothers’ cells so a TV journalist can stick her head into the enlarged air vent. The anniversary of the escape is coming up, and she needs a teaser shot for a segment she’s producing. “I got an inside look at the infamous cells,” she says in an on-camera journalist voice, “which are normally off-limits to the public.” Tourists crowd around, many of them families with young boys who, for the moment, have put away their video games and cellphones and even removed the headphones that come with the audio tour to stare into the concrete boxes where bad men lived squalid little lives. The boys jockey for position. “Did they leave from there?” one asks. “Did they make that hole?”

“Can we see the raft?” No one looks bored. Even the dads, in their shorts and ball caps and performance fleece, have questions for Cantwell. It’s been this way since soon after Tuggle’s movie was released. “I think Don Siegel told me that Paramount spent $1 million, which was a lot of money back then, in fixing up the prison to be what it was in the old days,” Tuggle says.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Today, about 1.5 million people visit the prison every year, peering into cells stocked with period-specific reading materials—Life, Sports Illustrated, and many copies of Popular Mechanics. They listen to the audio tour, which urges them to imagine eking out day after miserable day there. To imagine the creativity and dedication it would take to escape. Cantwell has watched many thousands of them, and he sees their emotional states transform as the tour brings them deeper and deeper inside the prison walls. “People are fascinated with the macabre,” he says. With irony, and hubris, and wrestling with the fat thumb of institutional power. When you take the tour of this lonely buoy in the middle of San Francisco Bay, part of you feels like, just maybe, Morris and the Anglins earned their freedom. Maybe even deserved it.

“The movie really changed the physical site, and then gave publicity to the escape."

And that’s a strange feeling.

“That’s the difficulty in being a writer of a true event,” says Tuggle. “In reality, Morris and the Anglins were probably bad guys . . . but for a movie, you can’t have that. I wanted to show what these guys did, and the only way to have the audience behind them was to make the characters nicer than they were in real life.”

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

As for Bayard Richard, whose one-off stunt in a hotel pool launched a butterfly effect that led to a prison escape, a movie, and the revitalization of a historic landmark, a question remains: Does he feel he played a part in creating a cult of personality around a trio of dudes you wouldn’t want to encounter in a San Francisco alley? “No,” he says. “It’s just the kind of thing you do when you’re in the magazine business.”

Popular Mechanics tells its readers how to make things. Always has, since 1902. When that information gets used illegally, there’s not much we can do about it. On one hand, the magazine doesn’t condone prison escapes. But there’s something about the way Morris and the Anglins went about it—they were nonviolent offenders who broke out of the most notorious prison in the world without harming so much as a seagull—that seems in the spirit of the magazine: decent, almost charming lawlessness, more Ocean’s 11 than Scarface. We’d rather hear a story about how that life jacket article kept a whole family safe during an afternoon boat ride, but who would make a movie about that?

Jacqueline Detwiler-George has a master's degree in neuroscience and has contributed to Wired, Esquire, Fast Company, and Best American Science and Nature Writing. She's the former articles editor at Popular Mechanics and former host of the Most Useful Podcast Ever.